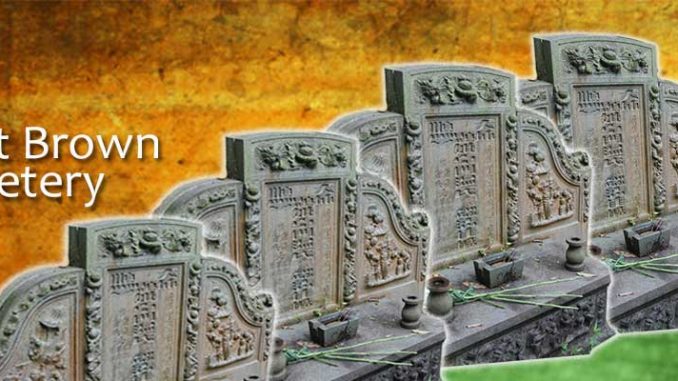

The Bukit Brown Controversy

Bukit Brown Cemetery is a large burial ground in Singapore. It was opened in 1922 by the British colonial government as a Chinese public cemetery. When it closed in 1973, the People’s Action Party (PAP) government adopted the policy of cremation for land-scarce Singapore. 1 Bukit Brown has about 100,000 graves, but cemeteries do not have a future in postcolonial Singapore.Bukit Brown re-emerged in the national spotlight in September 2011 when the government announced plans to build an 8-lane thoroughfare through part of the cemetery. The plan was to relieve traffic congestion in the area, but it meant the clearance of nearly 4,000 graves. 2 By this time, the cemetery was a shadow of its former self, with diminishing numbers of families going to pay respects to their ancestors during Qing Ming Festival and many of the gravestones falling into disrepair. Bukit Brown’s decline is part of its history.

Civil society groups and members of the public were angry that the Bukit Brown decision had been made without proper consultation. Heritage advocates like the Singapore Heritage Society (SHS), a local NGO, argued that the cemetery should be conserved because it provides Singaporeans with a sense of history and identity. 3 Another NGO, the Nature Society (Singapore, NSS), contended that the development of the green belt on which the cemetery sits would make the area prone to floods and endanger animal species. 4 SHS, NSS and other groups were subsequently consulted by state officials. Other heritage enthusiasts, bypassing the state, organised tours, forums and petitions, often using social media to attempt to save Bukit Brown. 5

The controversy gradually quietened down; the expressway project continued, the state had seemingly engaged its critics, including commissioning a project to document the cemetery’s history, and civil society groups had made a strong case for heritage.

Heritage of Great Chinese Men, History of Power and Wealth

Both heritage advocates and public officials agreed on Bukit Brown’s historical value, based on the notable men interred there, though they only represented a tiny fraction of the burials. The Singapore Heritage Society stressed that ‘tens of thousands of ordinary migrants are also buried at Bukit Brown..’ 6They were seen as ‘ordinary people who anonymously contributed their blood, sweat and toil to the development of our city port.’ 7 They remained that – anonymous – a label that never emerged in a concrete way to shape the conservation effort. Heritage enthusiasts painstakingly tracked down the graves of the illustrious men and shared photographs of their architecturally appealing tombstones. Virtually all the graves were of great Chinese men and the cultural practices upheld as heritage were Chinese ancestral worship and funeral rites. But class, ethnicity and gender issues were not debated. The heritage discourse converges with the masculinity and heroism of the official Singapore Story. A recent commissioned work on the PAP’s history was titled Men in White. 8

History should be more than a chronicle of great men. The classic works of Carl Trocki and James Warren have pointed to the role of Chinese elites in the development of Singapore’s entrepot port during the colonial era. Many of them found their wealth and status within the British imperial-capitalist system. In the nineteenth century, they controlled lucrative revenue farms, such as opium and spirit farms. They used opium, gambling, prostitution, and secret societies to mould poor, male Chinese sinkehs (fresh arrivals) into a subservient labour force, whose backbreaking work supported the trade of Singapore, and their businesses. 9 Drugs and sex pushed the working men to the limits of their bodies, and until secret societies were outlawed in 1890, there was no appreciable distinction between the merchants and triad leaders.

The emphasis on exceptional men is not only a problem of Bukit Brown: the use of the names of prominent Chinese (and non-Chinese) for important buildings and places in Singapore shows that the themes of elitism and success are deeply inscribed in the psyche and identity of Singaporeans. 10

The Cemetery: A History of Regulation and Contestation

The history of Bukit Brown is arguably a record of colonial attempts to rationalise Chinese burials and the contestation that resulted. From the start, the authorities required that burials be applied for and registered. They fixed the numbering, layout, size, depth, and fees for each burial lot. 11 As Brenda Yeoh observes, the control of cemeteries was part of a colonial policy to instil ‘modern’ (Anglo-centric) ways of organising society in place of Chinese customary practices. 12

This policy framework, however, Chinese community leaders continuously contested. The hilly location of Bukit Brown cemetery was a concession to their sensibilities: the British could not quite understand why the Chinese had to bury their dead in the hills while the working class languished in congested shophouse cubicles in the unhealthy valleys. The contestation showed the power of the Chinese mercantile community: the initial size restriction (a grave per plot) was soon relaxed and the upper classes were able to build graves over two plots. 13 This bequeathed a legacy of majestic tombs atop Bukit Brown.

The Kampongs: Living with the Dead

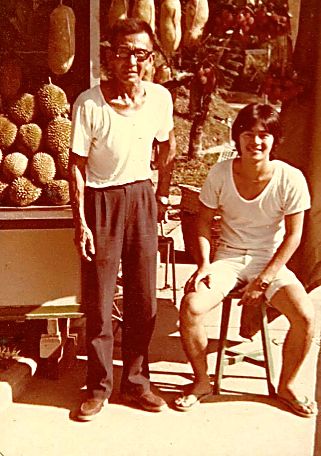

My oral history work on the documentation team for Bukit Brown enabled me to interview former residents of kampongs who lived next to the graves until they were resettled in public housing in the 1980s and early 1990s. Wooden settlements such as Kheam Hock Road, Lorong Halwa and Kampong Kubor provided economic and cultural services for the cemetery. Some village men worked as tomb-makers and stone-engravers, while others were caretakers of the graves. Male and female villagers also sold joss, food and drinks to visitors to the cemetery.

This social history contrasts with the chronicle of pioneers. It is also a foil to Singapore today, with its centralised state and culture of full-time employment in the formal economy. But it is not unusual that social history is ‘matter out of place’ in the grand narrative of great men. 14

The villagers had no fear of living near the dead. Formal Chinese culture holds that people revere their dead and bury them on high ground. However, for the villagers, pragmatism trumped cultural norms when living with the dead provided livelihood opportunities. As an interviewee surmised, the villagers were ‘good friends with the ghosts.’ 15 The British government also worried about sanitation, stipulating that the graves must be located a distance of at least 20 feet from a water source. 16 But residents once drank well water at the hilltop and vividly remembered the ‘si lang chap’ (juice from corpses) as clean and pure. 17

In one aspect, the kampongs of Bukit Brown differed from those elsewhere in Singapore. There was skill and culture involved in the work of the tomb-makers and stone-engravers. They were fairly well-off and resided in the larger houses in the more accessible areas in the villages. The tomb-makers had trading ties with stone exporters in China and Malaysia; local stone was considered inferior and used mainly by the working class. 18 The engravers, who could be a son of a tomb-maker, would learn the craft at a young age. It required nimble finger-work; long hours of practice bent over a piece of stone was backbreaking. 19

The caretakers and tomb-keepers were not merely grass cutters. Most of them had little education and did manual work trimming the grass, cleaning the tombstones and repainting faded inscriptions on old graves. Their real expertise derived from their view of a dangerous spirit world that was, however, governed by rules. As one of them explained, it was ‘not easy to earn money at the hill.’ 20 They had to perform rituals to appease the spirits before clearing the weeds or cutting downa tree. 21 They warned of the instances of caretakers who had perished because they had violated moral laws. 22

The Chinese and the small Malay minority residing near Bukit Brown were united by pragmatism. Some Malay men worked as keepers of Chinese tombs. Along the creeks in the area, Malay and Chinese women washed clothes together. Many Malays could speak some Hokkien, while Chinese could speak bazaar (colloquial) Malay. 23 This was the true multiculturalism of Bukit Brown.

Outside the Heritage Discourse

As Laurajane Smith notes, the heritage discourse is often ‘selected by experts and made to matter.’ 24 In their efforts to save Bukit Brown, advocates maintained that there was no tension between heritage and development; their solution, however, privileged the cemetery over the expressway. There was an interesting proposal from the Singapore Heritage Society to treat heritage sites as public goods, to be assessed with other public goods like roads. 25 In the main, though, the conservation discourse proposed a zero-sum game. Road users were excluded from it. In fact, some of them questioned the need for the expressway, pointing out that traffic congestion in the area occurred only during off-peak hours. 26

The enthusiasts brought their families and friends on the tours or shared events and photographs on Facebook. However, there was no attempt to mobilise opinion among people lacking an interest in Bukit Brown. In fact, those who were critical about conservation offered some nuanced ideas that the advocates unfortunately did not engage. One letter to the press criticised the ‘vocal minority’ of advocates for ignoring the housing needs of young couples (the cemetery had been zoned for housing in the long term). 27 Civil society groups in Singapore, lacking finance and manpower, are understandably weak. But this is not the full explanation. The exclusivity irked some people who complained about the narrow interests of conservationist groups. 28 Saving Bukit Brown was conceived as a one-sided and one-way campaign.

The most disappointing aspect of the conservation campaign was not engaging the people who were directly connected to the cemetery. A tomb-maker suggested to save the cemetery in part: the steel cemetery gates and selected tombs would salvage a sense of culture and history. 29For others, however, there was deep resignation to the necessity of change. A long-time resident of the area doubted that a dilapidated cemetery would appeal to many people.30 Another resident, a caretaker, felt that saving the cemetery would be difficult given the amount of money the government had spent on the expressway project. 30

With 100,000 graves in Bukit Brown, the views of the families of the deceased are difficult to determine. A few of them support conservation, such as the descendants of businessman Chew Boon Lay. 31 Interestingly, a young lady, Sharon Lim, related the story of her great-grandfather, one of the ‘people’ buried in the Paupers’ Section – a rare instance of history from below. 32 Some idea of public sentiment may also be gauged by the fact that less than a third of the affected graves – 1,005 – had been claimed by relatives of the deceased as of July 2012. 33 Although the low numbers might partly be due to the older graves being forgotten by their descendants, there exists a silent majority who are outside the dialogue between the state and heritage enthusiasts.

History in Heritage

To appropriate Ben Anderson, heritage is imagined in the same way the nation is. It is experts and elites who decide what has historical value and what should be saved. By experts and elites, I do not refer to people who are in high places; many heritage enthusiasts of Bukit Brown come from the community while some have loved ones buried there. Rather, I refer to the act of converting history to heritage, and of privileging heritage over development.

The world we live in demands that the past plays a role in our sense of well-being. Fast-paced development is erasing familiar landscapes and livelihoods. The historical discipline is often too fractured, inward-looking, and academic to produce stories that can capture the social imagination. History, too, is frequently a discourse of experts and elites. Many historical accounts – national ones comes to mind – are celebratory. But it is timely to include historical perspectives in the heritage discourse.

As heritage is singular, transfixed, celebratory, and neat, history offers multiple, contending accounts. Many historians accept that they each provide only an interpretation of the past. History traces its subjects through time and space, so objects of heritage will evolve, grow or diminish in history. Diverse accounts contain humanity’s dark deeds in addition to tales of achievement. An old place will have different memories for different people. As Singapore appears poised for greater political contention after the 2011 elections, so heritage advocacy must become more pluralistic and inclusive. The histories of Bukit Brown will be far richer than the story of a burial ground for great Chinese men, which merely celebrates ourselves.

Loh Kah Seng

Researcher, CSEAS

Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia. Issue 12 (September 2012). The Living and the Dead

Notes:

- Lily Kong and Brenda S. A. Yeoh, The Politics of Landscapes in Singapore: Constructions of “Nation” (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2003). ↩

- Straits Times, 20 June 2012. ↩

- The views and statements of SHS can be found on its website, http://www.singaporeheritage.org/?page_id=1352, last accessed 12 August 2012. I was then Honorary Secretary of the Society. ↩

- Nature Society (Singapore), Position on Bukit Brown, http://www.nss.org.sg/documents/Nature%20Society’s%20Position%20on%20Bukit%20Brown.pdf, last accessed 12 August 2012. ↩

- For instance, see All Things Bukit Brown: Heritage, Habitat, History, http://bukitbrown.com/main/, and Heritage Singapore: Bukit Brown Cemetery, https://www.facebook.com/groups/bukitbrown/, last accessed 12 August 2012. ↩

- Straits Times, 17 November 2011. ↩

- Singapore Heritage Society, Position Paper on Bukit Brown, January 2012, published online on 5 February 2012, http://www.singaporeheritage.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/SHS_BB_Position_Paper.pdf, last accessed 12 August 2012. ↩

- Sonny Yap, Richard Lim and Leong Weng Kam, Men in White: The Untold Story of Singapore’s Ruling Political Party (Singapore: Singapore Press Holdings, 2009). ↩

- Carl A. Trocki, Opium and Empire: Chinese Society in Colonial Singapore, 1800-1910 (Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1990); James Francis Warren, Rickshaw Coolie: A People’s History of Singapore, 1880-1940 (Singapore: Singapore University Press, 2003) and Ah Ku and Karayuki-san: Prostitution in Singapore, 1870-1940 (Singapore: Singapore University Press, 2003). ↩

- Victor R. Savage and Brenda S. A. Yeoh, Toponymics: A Study of Singapore Street Names, 2nd edition (Singapore: Eastern University Press, 2004). ↩

- Malayan Tribune, 30 August 1921. ↩

- Brenda S. A. Yeoh, Contesting Space in Colonial Singapore: Power Relations and the Urban Built Environment, 2nd edition (Singapore: Singapore University Press, 2003). ↩

- Malayan Tribune, 29 December 1923. ↩

- Karen F. Olwig, ‘The Burden of Heritage: Claiming a Place for a West Indian Culture’, American Ethnologist, 26 (2), May, 1999: 370-88. ↩

- Author’s interview with Ong See Tau and Koh Geok Khee, 21 December 2011. ↩

- Malayan Tribune, 30 August 1921. ↩

- Author’s interview with Chua Tiam Koon, 2 February 2012. ↩

- Author’s interview with Lee Cheng Hoe, 13 December 2011. ↩

- Author’s interview with Sunny Ng and Jenny Tan, 13 December 2011. ↩

- Author’s interview with Ah Tiong, 17 February 2012. ↩

- Author’s interview with Chua Tiam Koon, 2 February 2012. ↩

- Author’s interview with Ah Tiong, 17 February 2012. ↩

- Author’s interview with Tomirah Seban, 8 February 2012. ↩

- Laurajane Smith and Emma Waterton, Heritage, Communities and Archaeology (London: Duckworth, 2009), p. 29. ↩

- Singapore Heritage Society, Position Paper on Bukit Brown. ↩

- See first comment by ‘Guest’ under the article, REACH, ‘Government announces plans to document Bukit Brown cemetery heritage’, http://www.reach.gov.sg/YourSay/DiscussionForum/tabid/101/mode/1/Default.aspx?ssFormAction=[[ssBlogThread_VIEW]]&tid=[[4532]]#top, last accessed 12 August 2011. ↩

- Straits Times, 31 March 2012. ↩

- Straits Times, 22 March 2012. ↩

- Author’s interview with Lim Cheng Hoe, 13 December 2011. ↩

- Author’s interview with Ah Tiong, 17 February 2012. ↩

- Straits Times, 19 October 2011. ↩

- Sharon Lim, ‘My Great Grandfather, Lim Chu Guee’, a.t. Bukit Brown: Heritage, Habitat, History, March 2012, http://bukitbrown.com/main/?p=3285, last accessed 12 August 2012. ↩

- The deadline for submitting claims is the end of 2012. Straits Times, 13 July 2012. ↩