It is now common knowledge that whenever protest movements could make political gains through digital media and technologies, the regimes these very movements seek to challenge would catch up with their progress. From the 2010-2011 Arab Spring to popular contestations of Southeast Asia’s autocracies in 2020-2021, optimism regarding digital activism has been met with regime adoption of digital repression. 1 This development has reinforced ‘digital authoritarianism’ in the region. 2

Digital arsenals to suppress dissent have multiplied and diversified over the past decades, following disruptive mass mobilizations that challenged the status quo in countries such as Cambodia (2013), Malaysia (2015-16), Myanmar (2021-present), Thailand (2020-21) and Indonesia (2020). In long-standing autocracies like Vietnam in which the Internet is a potential regime destabilizer, stringent cyber laws and information manipulation through cyber troops enable ruling elites to tighten their grip on the population. 3 While domestic factors are key drivers, there is reason to believe that governments in Southeast Asia‘cross-learn’ tactics of digital repression and inspire one another. 4

Digital repression encompasses various methods of social control to preemptively deter and lower the impact of protest movements. Digital repression toolkits include Internet filtering, surveillance via high-tech spyware 5 and social media monitoring, state-aligned misinformation online, 6 prosecution of activists through cyber- or information-related laws, 7 and Internet shutdowns. 8 These can help governments achieve the goal of control, in many cases, without resorting to armed clampdown of challengers.

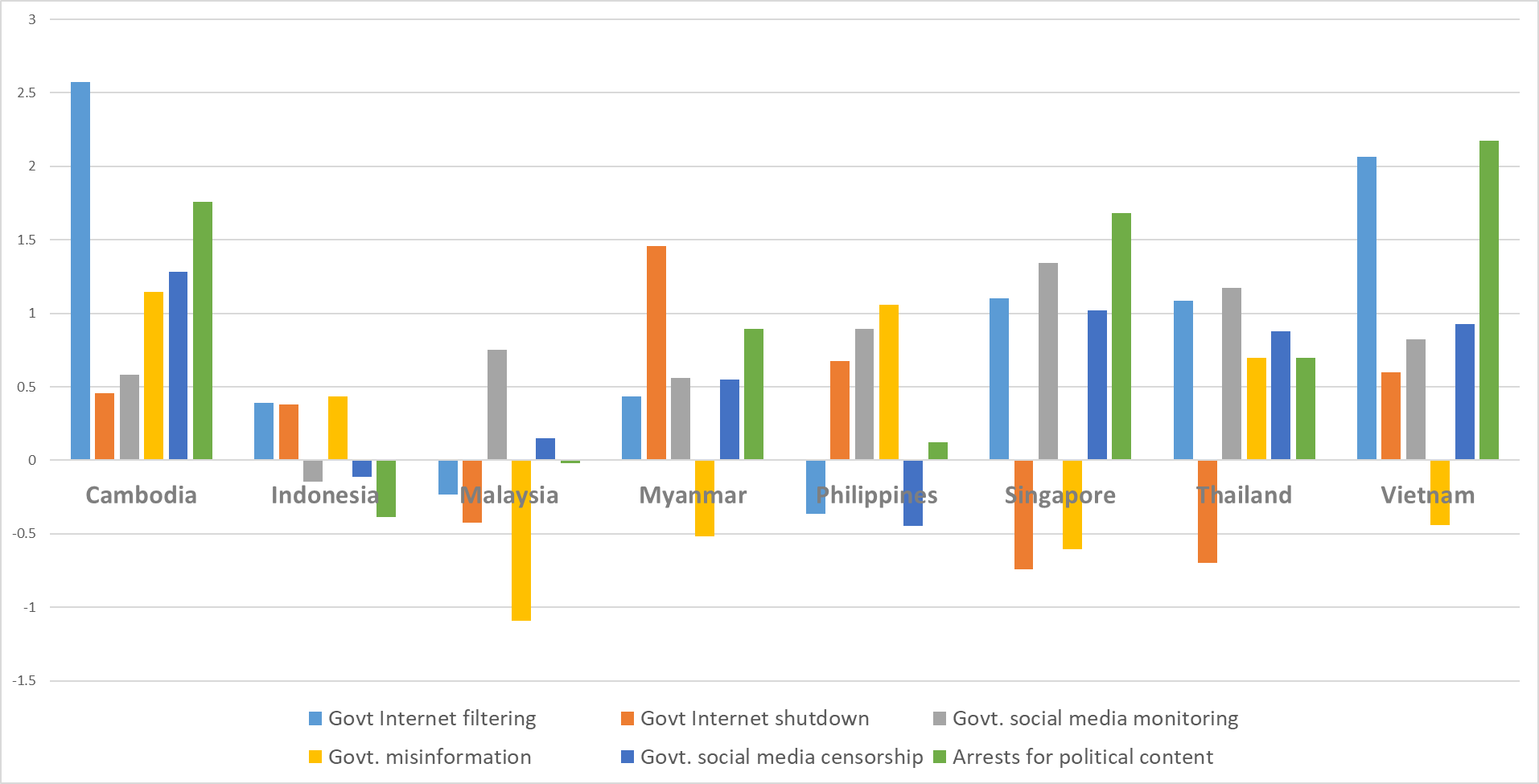

Governments in the region possess varying degrees of digital capacities, leading to their different tactical preferences. Based on the 2019 Digital Society Project data, the most oft-used form of digital repression in Singapore and Vietnam is prosecuting online users, while in Cambodia, it is Internet filtering. In Malaysia and Thailand, social media monitoring was the most common trend. The two remaining electoral democracies – Indonesia and the Philippines – lean toward misinformation campaigns. Myanmar seems to be the only one among its autocratic counterparts that most frequently relies on Internet shutdowns.

Figure 1

Digital repression scores in Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam

Most burgeoning studies and civil society reports tend to analyze the contour of an individual repertoire of digital repression. My ongoing research in Thailand, however, tells a different story. Repressive toolkits work in tandem, in an ecosystem; the operation of one repertoire complements the others. This is the case at least in Thailand. Its military-monarchy-backed regime has created the legal-bureaucratic infrastructure necessary for effective controls of digital space since the 2006 coup. The most crucial instrument is the 2007 Computer-related Crimes Act (CCA, amended from 2016 on), which does not only penalize those creating and/or sharing online content deemed ‘forged’ or ‘false’ that may cause public panic or threaten national security. 9 But it also gives a pretext for surveillance practices and developing relevant skills and technologies. This ecosystem of digital repression entails the interplay of online content filtering, digital surveillance, legal persecution of online users, and Information Operations (IO).

Notably, digital surveillance through social media monitoring and the use of snooping devices provides essential intelligence for the authorities to implement other tactics. Cyber units of the police, the army, and royalist civic groups would monitor social media feeds, at times using artificial intelligence-powered tools. They would flag content deemed to offend the monarchy or violate the CCA for lawsuits. In the aftermath of the 2020-2021 protests that, among others, demanded the monarchy reform, digital surveillance has intensified, involving the deployment of spyware like Pegasus that requires no malware or phishing links to infect targeted devices. This has reportedly offered the authorities exclusive information into the Thai protest movements, especially regarding their internal dynamics, plans for future activities, financial routes and supporters, and specific roles of activists that are normally kept confidential. For activists, the information has prompted preemptive crowd controls and most importantly arrests of activists. 10

A telling case is the activist P (alias) whose mobile phone was repeatedly attacked by Pegasus. Her name appears on a bank account that received public donations for the 2020 protest activities. On 17 September 2021, cyber police raided her apartment and charged her with Article 116 (sedition) and CCA. She believed that the arrest was also due to her additional role in the movement, which she believed was not public knowledge. She was accused of running the movement’s Facebook page. P is puzzled by the authorities’ insights into this role because she had kept it a secret and never used a personal account to operate the group’s official account. 11

Moreover, the information gained from social media monitoring and possibly surveillance tools could make online smear campaigns increasingly targeted. Through platforms such as Facebook and Twitter, cyber units related to security agencies and royalist civic groups have painted the 2020-2021 protesters as ‘nation-haters’ and ‘foreign lackeys’. 12 What is more, exclusive insights into, for instance, the financial avenues of protesters or their internal disputes, have recently sharpened messages of IOs attacking movement leaders as lacking transparency at best and having a moral deficit at worst. Such allegations could worsen movement fragmentation, a persistent challenge that has hindered the substantive advancement of its campaigns. 13

Lastly, online smear campaigns are closely intertwined with charges against activists. Those involved in these campaigns simultaneously file lawsuits against activists accused of undermining the monarchy. Throughout 2020 and 2021, smear campaigns on social media often interpreted activists’ demands vis-à-vis the current government and/or the monarchy as a threat to the nation and its pillars. These messages stigmatize activists and often give ground to those determined to defend the nation to take action. 14 Online stigmatization has sometimes led to physical attacks on activists, as evident in the case of Ja New in 2019. But lately, it has encouraged royalist activists, who want to do good deeds for the nation, to press charges against leading and rank-and-file dissidents for breaching Article 112 (offending the monarchy). A case in point is the Thailand Help Center for Cyber Bullying Victims (THCVC) whose members were trained to file an Article 112 complaint and have received evidence for lawsuits from the private chat group. These royalist activists deliberately file complaints at a provincial police station far from the accused’s residences to create extra hurdles such as travel costs and time spent on the trips. 15 Between November 2020 and November 2022, there have been 239 cases of Article 112. Of this number, ‘ordinary citizens’, including members of the THCVC and the royalist Thai Bhakdi, filed 109 complaints. 16

So far, it remains difficult to assess the detrimental impact of digital repression on protest campaigns in Thailand specifically and Southeast Asia generally. What studies in repression and social movements can tell us is that digital repression contributes to disrupting and disorienting movements’ public communication and strategies of mass mobilization. In addition, the prosecution of digital activists can deplete their limited resources – be it time, money, and energy – by forcing them to fight in countless court cases. 17 This together with digital surveillance and online smear campaigns can take a toll on activists’ wellbeing and private lives. Some dissidents I interviewed told anecdotes of fear, exhaustion, and anxiety from being spied on, charged, and demonized for doing what they believe is for Thailand’s better future. Few of them, especially rank-and-file supporters became discouraged from partaking in protests. Ultimately, the repression has raised the costs of mass mobilization, particularly in the digital space. The prospect of countering its long-term effects remains dimmed.

Janjira Sombatpoonsiri

Assistant Professor and Project Leader

Monitoring Centre on Organised Violence Events, Thailand

Notes:

- See, for instance, Steven Feldstein, The rise of digital repression: How technology is reshaping power, politics, and resistance (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2021); Erica Frantz, et al. “Digital repression in autocracies. V-Dem Working Paper,” 2020, https://www.v-dem.net/media/publications/digital-repression17mar.pdf ↩

- See more in, “The spectre of digital authoritarianism in Southeast Asia,” Kyoto Review 33, https://kyotoreview.org/issue-33/from-the-editor-the-spectre-of-digital-authoritarianism-for-southeast-asia/ ↩

- Janjira Sombatpoonsiri and Dien Nyugen An Luong, Justifying Digital Repression Via Fighting ‘Fake News’: A Study of Four Southeast Asian Autocracies (Singapore: ISEAS Yusof-Ishak Institute, 2022), https://www.iseas.edu.sg/articles-commentaries/trends-in-southeast-asia/justifying-digital-repression-via-fighting-fake-news-a-study-of-four-southeast-asian-autocracies-by-janjira-sombatpoonsiri-and-dien-nguyen-an-luong/ ↩

- For instance, after the 2018 discussion between the Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen and his Vietnamese counterpart Nguyen Xuân Phúc regarding how to deal with ‘inaccurate news,’ the Cambodia’s ruling party stepped up the crackdown on the media accused of spreading the ‘wrong information’. See, Ate Hoekstra Phnom Penh, “Cambodia proposes law targeting ‘fake news’,” Deutsche Welle, 4 October 2018, https://www.dw.com/en/cambodia-considers-new-law-targeting-fake-news/a-43323565 ↩

- Bill Marczack et al., “Hide and seek: Tracking NSO’ spyware to operations in 45 countries,” The Citizen Lab, 2018, https://citizenlab.ca/2018/09/hide-and-seek-tracking-nso-groups-pegasus-spyware-to-operations-in-45-countries/ ↩

- For instance, Jonathan C. Ong and Jason Vincent A. Cabañes, “Architect of networked disinformation: Behind the scenes of troll accounts and fake news production in the Philippines,” The Newton Tech4Dev Network, 2018, https://scholarworks.umass.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1075&context=communication_faculty_pubs ↩

- For instance, Ric Neo, “When would a state cracks down on fake news? Explaining variation in the governance of fake news in Asia-Pacific,” Political Studies View 20(3), https://doi.org/10.1177/1478929921101398 ↩

- For instance, Steven Feldstein, “Government Internet crackdowns are changing. What should citizens and democracies respond?”, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, March 2022, https://carnegieendowment.org/files/Feldstein_Internet_shutdowns_final.pdf ↩

- Royal Gazette, “Computer-Related Crimes Act, B.E. 2550 (2007), no. 124, sect. 27 kor”, https://www.tsu.ac.th/files/Computer_Crimes_Act_B.E._2550_Thai.pdf; Royal Gazette, “Computer-Related Crimes Act B.E. 2560 (2016), no. 134, sect. 10 kor. http://www.ratchakitcha.soc.go.th/DATA/PDF/2560/A/010/24.PDF ↩

- These insights are drawn from my interviews with 10 activists and movement supporters targeted by Pegasus. The interviews were conducted in July and August 2022. ↩

- Interview with P, August 2022. ↩

- Janjira Sombatpoonsiri, “ ‘We are independent trolls’: The efficacy of royalist digital activism in Thailand,” Perspective 2022/1, ISEAS Yusof-Ishak Institute, https://www.iseas.edu.sg/articles-commentaries/iseas-perspective/2022-1-we-are-independent-trolls-the-efficacy-of-royalist-digital-activism-in-thailand-by-janjira-sombatpoonsiri/ ↩

- See, Hardy Merriman, “The trifecta of civil resistance: Unity, planning, discipline,” International Center for Nonviolent Conflicts, 19 November 2010, https://www.nonviolent-conflict.org/resource/the-trifecta-of-civil-resistance-unity-planning-discipline/ ↩

- See similar insights in the case of Colombia and Guatemala in Richard Wilson, “The anti-human rights machine: Digital authoritarianism and the global assault on human rights,” University of Connecticut, Faculty Articles and Papers, 2022, https://opencommons.uconn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1614&context=law_papers ↩

- VoiceTV, “Mapping 112 lawsuits, citizens against citizens,” 29 October 2021, https://voicetv.co.th/read/xZ3RycdVl ↩

- Thailand Lawyers for Human Rights, “Numbers of those charged with Article 112 from 2020 to 2022,” 22 November 2022, https://tlhr2014.com/archives/23983 ↩

- Jules Boykoff, “Limiting dissent: The mechanisms of state repression in the USA,” Social Movement Studies 6(3) (2007): 281-310. ↩