Over the past fifteen years, politics have stagnated and democracy has faltered in Southeast Asia. The region has gone from a bellwether of global democratization, with countries such as Indonesia, Thailand, Malaysia, and the Philippines making breaks from dictatorial pasts, to a center of the new era of authoritarianism. Now, Southeast Asian states often are led by politicians, such as the Philippines’ Rodrigo Duterte, who win elections, destroy any institutions that could constrain their power and use social media to whip up supporters with misinformation and attacks on a wide range of minority groups. At the same time, retrograde authoritarianism has returned to Southeast Asia as well, in the form of outright military juntas, like the brutal one that rules Myanmar, and acts in some ways like it is carrying on strategies from the isolated, xenophobia military rulers that dominated Myanmar between the early 1960s and late 1980s.

Meanwhile, after fending off the pandemic in 2020, the region has faced a massive COVID-19 outbreak this year. The new wave is decimating populations and causing massive economic damage, while also sparking ferment against the political order. Even states like Vietnam and Thailand that had largely been spared by the pandemic in 2020, with minimal caseloads and few deaths, now face rising caseloads and deaths. Some, like Vietnam, which along with countries such as Australia and New Zealand and China had adopted “zero Covid” strategies of attempting to eliminate the virus, have backed off, with Vietnamese leaders moving toward an admission that the virus cannot be quashed, and that Vietnamese people will have to live with the virus in the long term, as it hopefully becomes less dangerous over time.

Yet at the same time, the rising caseloads and deaths across Southeast Asia has sparked a feeling, among many populations, that the region’s leaders, nearly all of whom are autocratic, have mishandled this year of COVID-19, and particularly have mishandled the outbreak of the Delta variant and the race to vaccinate populations. While the region’s more authoritarian leaders are fairly entrenched, and some have the power of the armed forces on their sides, this wave of COVID-sparked protest, often led by younger people already fed up with regional leaders, has the possibility of upending the regional order.

Between the 1980s and the early 2000s, Southeast Asia was at the center of a global wave of democratization. Thailand, Indonesia, the Philippines, and East Timor all became democracies, and countries like Cambodia, Malaysia, and Myanmar launched political reforms. By the early 2000s, Freedom House ranked Thailand a full democracy and other organizations considered Indonesia, the Philippines and East Timor flourishing democracies as well. Although Cambodian prime minister Hun Sen had toppled a coalition government with a coup in 1997, and never seemed willing to really let go of political power, he did allow some degree of political opposition, as well as one of the most vibrant civil societies in the region. Similarly, although Malaysian leaders used gerrymandering, voter suppression and fraud to prevent the opposition, until 2018, from winning a general election, the opposition remained powerful, especially in urban areas, and an independent press and civil society blossomed.

But since the late 2000s, the region has regressed politically, part of a global wave of democratic backsliding that seems to be gathering pace. Authoritarian populists in Southeast Asia have undermined freedoms in the Philippines, Cambodia, and Thailand; military juntas have further crushed democracy in Thailand and, most notably, Myanmar. Seemingly promising reformers, like Indonesian president Joko Widodo, have faltered in battles against corruption and once again empowered antidemocratic actors like the armed forces, while in Malaysia the opposition coalition that won power, for the first time, in the 2018 elections wound up fighting with itself and making little headway in promoting major reforms. The most repressive regional states, like Vietnam, actually have become more authoritarian in the past decade, with Hanoi cracking down on the few independent writers, bloggers, and other journalists operating in Vietnamese society and beginning to curtail the general public’s social media usage as well. The main regional organization, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, has done little amidst coups and other reversals, even when autocrats wield the most brutal types of repression, like the Myanmar junta, which has killed over a 1,000 people, launched scorched earth policies against the opposition, and jailed journalists, activists, medical professionals, and religious leaders. Today, East Timor remains the only fully free democracy in Southeast Asia.

In the first year of the pandemic, Southeast Asia survived COVID-19 mostly unscathed. Indonesia and the Philippines faced sizable outbreaks, but caseloads remained minimal in Thailand, Vietnam, Singapore, and even impoverished Myanmar. (Vietnam, a country of roughly 96 million people, was reporting just a handful of cases per day and virtually no deaths.) Leaders in places like Thailand, Singapore, and Vietnam instituted effective policies on mask wearing, contact tracing, closing borders, and quarantining. The reasons why poorer countries in the region, such as Cambodia and Myanmar and Laos, did not seem to have many COVID-19 cases remains somewhat obscure. Some of the states, like Myanmar, instituted relatively effective public health measures that probably helped curtail the pandemic’s spread. But others, like Cambodia, did relatively little and had low caseloads, though the reported figures probably differ somewhat from the actual numbers, given the difficulty of reaching many people in Cambodia and Laos and the repressive nature of the governments. Nonetheless, much of Southeast Asia remained, in 2020, one of the biggest pandemic success stories, especially compared to wealthier states in North America and Europe, which suffered extremely high caseloads and death tolls.

In 2021, however, the inflexibility and repression of Southeast Asian governments has hampered the battle against the virus. While the region’s autocrats were able to manage COVID-19 at first with techniques that depended on central control like border closures—while also forestalling public anger by banning large gatherings—in 2021 authoritarian governments have faltered as the challenge has shifted. Southeast Asian states have struggled to get their populations vaccinated; three of eleven countries in the region have vaccinated over 60 percent of their eligible populations. To be fair, the poorer countries in the region have struggled with vaccination just like many other lower-income states around the world, but even middle-income Southeast Asian countries, like Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, and the Philippines have not had widespread vaccinations. Meanwhile, countries like Vietnam have struggled in trying to switch away from a “zero-COVID” approach, which they touted in 2020, to a more flexible pandemic strategy that accepts the idea that populaces must, to some degree, live with the disease while working to minimize its health effects, get people vaccinated, and hope that COVID-19 becomes less virulent over time.

Often, these failures stem from corrupt and autocratic politics, or from political situations in which leaders spend their time battling each other rather than the virus. The Thai government originally handed domestic vaccine production over to a company, controlled by the Thai king, that had no real experience making vaccines, and that firm struggled to ramp up vaccine production. The Myanmar junta, meanwhile, appears to be withholding vaccines from political opponents, and favoring health care services for people it can verify as favorable to the armed forces and the junta government. In Malaysia, politicians spent much of 2020 and 2021 trying to , and eventually succeeding in, topple each other’s parliamentary coalitions, and using pandemic-era emergency orders to boost their political powers rather than trying to halt the virus’s spread. While these Malaysian leaders fought and attempted to secure their political futures, they failed to develop a clear approach toward the pandemic, even in a country with the financial resources to develop an effective COVID-19 strategy.

Today, Southeast Asia is struggling with one of the worst COVID-19 outbreaks in the world, and the real caseloads and death tolls from the disease in the region may actually be much higher than public reported by Southeast Asian governments. Since the February 2021 coup, Myanmar has collapsed into a situation akin to a failed state, with pandemic patients dying at home, unable to get oxygen, vaccines, or medication, and the country’s failures spreading the virus further into China and likely into other parts of mainland Southeast Asia as well. Indeed, Myanmar seems to be developing into a “superspreader” state, and may well be responsible for passing on more virulent strains of the virus in the coming months or year. Malaysia now has one of the highest per capita daily cases of COVID-19 of any country in the world. Thailand was, in September, recording around 13,000 new cases per day, and other Southeast Asian countries like Indonesia also have suffered massive outbreaks and high death tolls in the past year. Meanwhile, a recent study by the Economist suggested that, although Southeast Asian states publicly have reported about 217,000 COVID-19 deaths since the beginning of the pandemic, the real figure may be at least 2.5 to 8 times higher, because of concealing of reported cases and the inability for public health authorities to identify caseloads in rural and hard to access parts of the region.

The pandemic era, though a public health disaster in Southeast Asia (as well as in most of the world) may prompt the biggest political changes in Southeast Asia since the 1990s. Even in places where autocrats are holding on, failing efforts to control the virus have damaged leaders’ legitimacy, as the pandemic has done in other parts of the world where leaders have struggled to contain COVID-19. The spread of COVID-19 and the subsequent economic damage has made people even more desperate in countries like Thailand, the Philippines, Indonesia, Myanmar, and Malaysia, among other states where anger already was rising over inequality and where countries are recorded their contractions in decades. Partly as a result, public protests were erupting more often. Large anti-government protests have taken place in 2021 in Thailand and Myanmar, and Malaysia’s government collapsed in 2021.

Even in normally placid Singapore, the usually dominant People’s Action Party (PAP) called an election amidst the pandemic and won re-election, but the opposition put up a strong result, as the PAP lost nine percentage points in the popular vote share as compared to the 2015 general election. After the mediocre showing (by its standards) in the 2020 general election, the PAP’s prospective prime minister candidate, Heng Swee Keat, took himself out of the running for the job, leaving the PAP looking less of a well-oiled machine than it had in past years. In addition to the weaker general election result, Heng Swee Keat’s ticket in the East Coast GRC had barely defeated the opposition ticket, hardly what PAP leaders must have wanted to see from a possible next prime minister.

Southeast Asian reformers who want to capitalize on the discontent brewing over the virus and its economic effects face high hurdles to converting anger into real political change. The regime’s leaders are often either so brutal that they can crush opposition or, as Lee Morgenbesser has noted in a recent book, have become sophisticated enough to co-opt opposition and defang reform movements.

The Myanmar junta falls into the first camp: It clearly will kill protesting civilians. The Thai military, police, and current government also use brutal force against demonstrators and other opponents, and in Thailand, as in Myanmar, there is always the possibility that the armed forces will end a period of protest with a coup, even against a government that already has been installed by the army. Leaders in the region, even in freer states like Indonesia, also use skewed courts, unfair election rolls, laws constraining print and online reporters, police and army intimidation, and other tools of a more sophisticated authoritarianism to stifle dissent.

Despite the pandemic’s health and economic toll, autocratic leaders in Southeast Asia are clearly digging for more years in power, and sometimes attempting to use legal changes or quasi-legal maneuvers to retain de facto control. In the Philippines, for instance, President Rodrigo Duterte is trying to sidestep term limits on the presidency that allow for only one single, six-year term and run for vice president in 2022. (Other autocratic leaders in different parts of the world have used similar measures, like Vladimir Putin shifting from president to prime minister and then running again for president.) As veep, he would presumably wield real political power, instead of the placeholder president, presumably longtime Duterte ally Bong Go, close to Duterte and likely willing to do his bidding.

Still, tarnished governments now face a different political reality, even with all the tools of power at their disposal. Unlike leaders of Myanmar, Vietnam or Cambodia, most Southeast Asian politicians are unable to simply rule by force; they require some degree of popular legitimacy even when they use other tools to constrain political and civil society opposition. They call elections that, while often not fully free and fair, do have the possibility of a loss for ruling parties, they preside over parliaments that debate and even censure the government, and they operate in countries with active, if often legally constrained, civil societies. And now, publics crave political leaders who will prioritize effective public health strategies over politicking, partisanship, and repression, and see that the current wave of leaders, such as Thai prime minister Prayuth Chan-ocha, cannot pass this test.

In a sign of how this hunger for competent governance can reshape politics, Malaysia’s leading reformist party made an alliance with the long-dominant party, United Malays National Organisation (UMNO), to run the country together and develop new pandemic strategies. After more than a year of political battles and ineffective government, the move likely will enjoy high levels of popular support. It also will put Malaysian reformers in position to potentially win power the next time national elections are called, provided the government adopts a more effective pandemic strategy. After all, in other regions of the world, failed pandemic policies have led publics to oust leaders or turn sharply against them, from U.S. President Donald Trump to Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro. Although many Southeast Asian states are more repressive than the United States or Brazil, the pandemic has been so destructive that it might spark political change.

Joshua Kurlantzick

This column is adapted from the Council on Foreign Relations In Brief “Is COVID-19 Shaking up Politics in Southeast Asia?“, which is at https://www.cfr.org/

Joshua Kurlantzick is senior fellow for Southeast Asia at the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR). He is the author, most recently, of “A Great Place to Have a War: America in Laos and the Birth of a Military CIA”. Kurlantzick was previously a visiting scholar at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, where he studied Southeast Asian politics and economics and China’s relations with Southeast Asia, including Chinese investment, aid, and diplomacy. Previously, he was a fellow at the University of Southern California Center on Public Diplomacy and a fellow at the Pacific Council on International Policy.

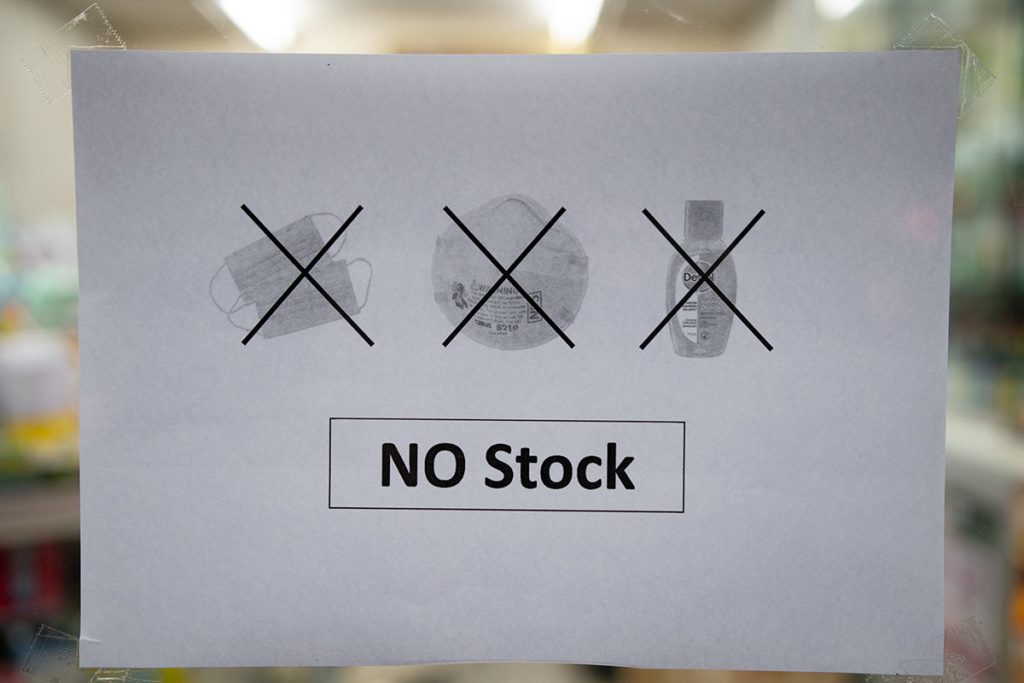

Banner: Facemasks at farmers market in Thailand. Photo by