Since the start of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, the relationship between the two great powers, Russia and China, has been much discussed and debated in international relations. What is the nature of the Sino-Russian alignment? Is it a strategic alliance or a convenient partnership? What is China’s role and position in the war? What influence will China have over Russia’s conduct of the war?

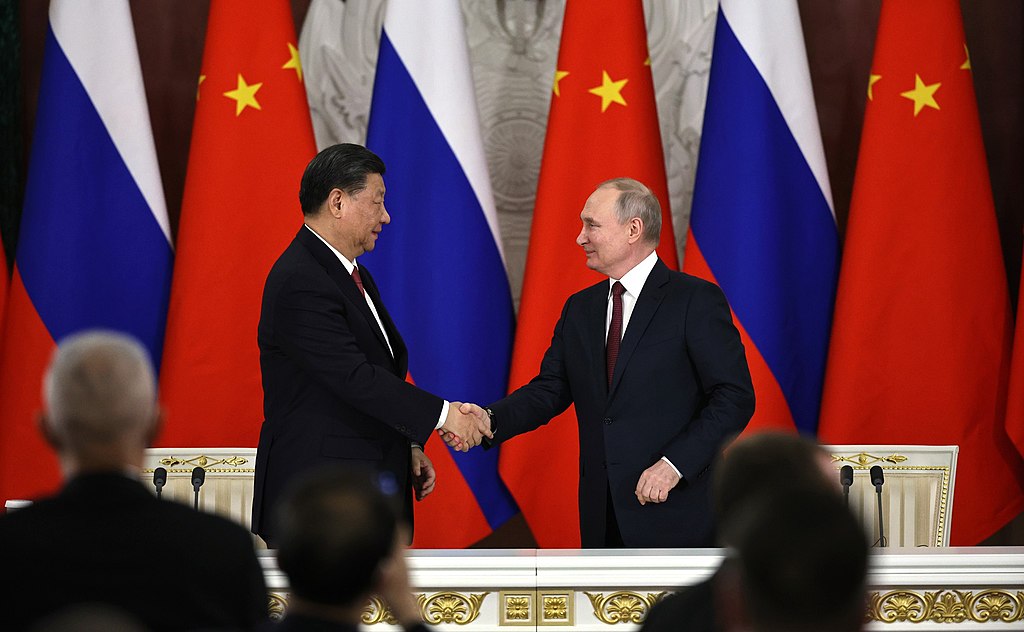

Closer ties between Russia and China have often been characterized as an “axis of authoritarians” or an “axis of revisionists” for their efforts to reshape the global system. 1 Shortly before the Russo-Ukrainian War, Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin even call their relationship a “no-limits partnership”. This article argues, rather, that the wartime relationship between Russia and China is an ambivalent and awkward partnership in which they cooperate only in certain key areas of mutual strategic interests.

First of all, China’s position on Russia’s war in Ukraine is mixed. Beijing has neither condemned the war nor fully endorsed Moscow’s geopolitical adventure. China has blamed the West for continually ignoring Russia’s security concerns, and it abstained from the UNSC/UNGA resolutions condemning Russia. On the other hand, Xi has not recognized Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea or the independent status of Donetsk and Luhansk, the two political entities in the occupied Donbas.

Second, Russia needs China more than China needs Russia. The unprecedented Western sanctions against Russia and Russia’s expulsion from the SWIFT international financial system leave Moscow far more reliant on China as an alternative economy. 2 Bilateral trade in the first four months of 2022 increased by 25.9 percent, and Russian exports to China grew by 37.8 percent. Russia’s natural gas exports to China increased by 15 percent. 3 Thus, the war has led to an asymmetrical relationship in which Moscow is increasingly dependent on China but not vice versa. 4 Today, it is China, not Russia that is the big brother in their relationship.

Third, Russia’s war in Ukraine risks jeopardizing China’s core interest in defending sovereignty and noninterference in internal affairs. For Beijing, Ukraine is not comparable to Taiwan, since Ukraine is a sovereign nation while Taiwan is internationally recognized as part of China. Russia’s invasion might establish precedents and pretexts for external powers to facilitate or defend a declaration of independence by Taiwan. Rather than emboldening China to invade Taiwan, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine can be seen as a threat to China’s core interests there, which are not congruent with Russia’s.

Fourth, the war benefits China in at least two ways. China gains geostrategically in the short term, because the United States has shifted its attention from the Indo-Pacific to transatlantic relations and European security (although the escalating situation in the Taiwan Strait—especially since the recent high-level visit by U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi—is likely to change that equation).

Moreover, the war pushes Moscow towards a Chinese-led international order and accelerates the formation of a bipolar world. Russia and China share the goal of counterbalancing U.S. hegemony and supplanting the liberal rules-based international order. Both powers are seeking to develop an alternative to the G7, founded on the BRICS+ framework. 5 The war turns out to enhance this alliance by default. In other words, Ukraine’s losses are China’s gains.

Far from being a full-fledged autocratic quasi-alliance, the Sino-Russian partnership is driven by their common rivalry with the United States and constrained by their often divergent interests. The war in Ukraine exposes the imbalances and inherent limits of this partnership, and its resilience and future prospects remain uncertain.

‘The Russo-Ukrainian War’ in Thai Politics of Foreign Policy

While Russia’s assault on Ukraine has revitalized the collective solidarity among NATO and European countries, it has received mixed responses in Southeast Asia. Given the fact that the region is relatively distant from Ukraine, and that Russia is a nuclear and energy superpower, many ASEAN states are reluctant to take any unnecessary steps, 6 but the conflict has led to a spike in food and energy prices while affecting regional growth, inflation, and monetary policy in the long run.

In Thailand, the war is viewed through the lens of national politics, the left-right political spectrum, and the generation gap. Although the government’s rhetoric has been neutral, among the general public and on social media the war is seen as a black-and-white moral issue. Right-wing conservatives are likely to be pro-Russian, while the left-wing and liberals are pro-Western and pro-Ukrainian.

Thai conservatives cherish the long-standing friendship and diplomatic relations with Russia, which they see as an old friend that helped modern Siam survive the colonial era. 7 Despite voting to deplore Russia’s attack, Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha said that Thailand would remain neutral in the conflict. Foreign Minister Don Pramudwinai was reported to say that there was no need for Thailand to “rush into playing a role.” 8

Liberals and the younger generation in Thailand are critical of this policy stance and the oft-cited tradition of “bamboo diplomacy”—bending with the wind. Some call the official Thai position “spineless” and lacking all principle. They call for a stronger stance against Russia’s aggression. In Thailand, the war in Ukraine is largely perceived through the prism of internal political contestation. 9

Despite their historic friendship, however, Thai-Russian relations in general have little more than marginal significance in the current context of Thailand’s so-called hedging between the United States, a major treaty ally, and China, its largest economic partner. With little real substance to their relationship, Thailand and Russia are not strategic partners, and this is not going to change in the near future.

The Year Ahead?

The Russo-Ukrainian War has now lasted a number of years, with grave repercussions for global peace and prosperity: shortages of food and energy, soaring prices, and rising inflation. The way forward is uncertain and unsettled. Russia and the West have blamed and sanctioned each other. Supporters on both sides are descending into a polarized, “good versus evil” view of the conflict.

What is to be done? The first recommendation is for international society to take a principled stance, consistent with the UN Charter, and call for the cessation of violence and for humanitarian assistance to the Ukrainian people. Although the war is legally and morally wrong, this call should eschew ideological demonization and shun Cold War thinking: pressuring states to take sides in this war will only exacerbate conflict within and among them.

The second recommendation is that, given the awkwardness and ambivalence of the Sino-Russian partnership, international society should pursue a wedge strategy to slow or prevent the further alignment of these two powers, and it should seek to cooperate with Beijing where possible to utilize China’s roles for the greater good. The only powerful country with leverage over Putin’s Russia is Xi’s China, and although China has said repeatedly that it will not involve itself in the conflict, the need to safeguard its own interests in an interdependent world could make Beijing an, if not the, ideal mediator. 10

In the era of global turbulence, China and Russia remain two key international players. Their alignment is not a formal military alliance but rather ambivalent and awkward, with contrasting and sometimes competing stakes in Eurasia and beyond. Beijing and Moscow cooperate when they can and compete when they must. They are neither permanent friends nor strategic foes. They are merely friends with benefits. Despite the limits of no-limits partnership, however, a longer war in Ukraine is likely to transform these two contending powers into closer allies and tilt the world toward a more bipolar international order.

Jittipat Poonkham

Jittipat Poonkham is Associate Professor of International Relations and Associate Dean for Academic and International Affairs in the Faculty of Political Science, Thammasat University, Thailand. He is an author of A Genealogy of Bamboo Diplomacy: The Politics of Thai Détente with Russia and China (Canberra: Australian National University Press, 2022) and a co-editor of International Relations as a Discipline in Thailand: Theory and Sub-fields (London: Routledge, 2019).

Banner image: Ukrainian T-72AV with a white cross during the 2022 Ukrainian Kharkiv counteroffensive, September 2022

Notes:

- Richard J. Ellings and Robert Sutter, eds., Axis of Authoritarians: Implications of China-Russia Cooperation (Seattle and Washington, D.C.: The National Bureau of Asian Research, 2018); Angela Stent, “Russia and China: Axis of Revisionists?” Global China, The Brookings Institution, February 2020, https://www.brookings.edu/research/russia-and-china-axis-of-revisionists/. ↩

- Bobo Lo, Turning Point? Putin, Xi, and the Russian Invasion of Ukraine (Lowy Institute, 2022), https://www.lowyinstitute.org/publications/turning-point-putin-xi-and-russian-invasion-ukraine. ↩

- Vasily Kashin, “Ukraine’s Losses Are China’s Gains,” East Asia Forum, June 16, 2022, https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2022/06/16/ukraines-losses-are-chinas-gains/. ↩

- China is currently Russia’s largest trading partner, accounting for 18 percent of Russia’s trade in 2021, while Moscow represented just 2 percent of China’s trade. “China’s Economic and Trade Ties with Russia,” Congressional Research Service, May 24, 2022, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF12120. ↩

- Paul Poast, “The BRICS Summit Isn’t Just a ‘Talk Shop’ Anymore,” World Politics Review, July 8, 2022, https://www.worldpoliticsreview.com/articles/30665/with-latest-summit-brics-shows-it-s-not-just-a-talk-shop. ↩

- The reactions of ASEAN members have been varied. While Myanmar’s military junta has become a close friend with Moscow, Vietnam and Thailand have maintained a neutral stance, refusing to either condemn or condone Russia’s actions directly and calling for a peaceful diplomatic resolution to the conflict. Singapore has taken the strongest stance, imposing outright sanctions on Russia. Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines are aligned in their positions on the war. Interestingly, Cambodia, the 2022 chair of ASEAN, has taken a tougher stance on Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. See Ian Storey and William Choong, “Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine: Southeast Asian Responses and Why the Conflict Matters to the Region,” Perspective, ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute, No. 24 (2022), 1–13. ↩

- This is illustrated by the iconic images of King Rama V and Tsar Nicholas II, which were taken when the former visited St. Petersburg in 1897. These images have served as the glue between Thailand and Russia ever since, despite ups and downs in bilateral relations. ↩

- Quoted in Pisan Manawapat and Jakkrit Srivali, “Thailand Must Take Stand on Ukraine,” Bangkok Post, March 11, 2022, https://www.bangkokpost.com/opinion/opinion/2277571/thailand-must-take-stand-on-ukraine. ↩

- To be sure, these deeply divided domestic politics existed even before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and will persist in the future. ↩

- “Scholars see Beijing as Ideal War Mediator,” Bangkok Post, March 5, 2022, https://www.bangkokpost.com/thailand/general/2274143/scholars-see-beijing-as-ideal-war-mediator. ↩