There is an emergent digital culture in the art and cultural sector in Hanoi, Vietnam, which is producing a shift in the nature of work for cultural professionals, the way of preserving and displaying art collections as well as the nature of international connections. This is an important shift in the cultural sector because digitization processes provide an increased agency for cultural professionals to present their own image of Vietnamese culture to an international audience. Cultural professionals are now the ‘mediators’ of Vietnamese culture on an international scale. Digitization of artworks and museum collections as well as making this content accessible online via digital platforms is vital to foster more international connection and allows these professionals to tell their own story about Vietnamese culture. They now have the ability to raise awareness internationally on, for instance, traditional and contemporary photography or lacquer painting. This includes subject matter that is not so often seen globally online, which helps to update the commonly shared images and narratives that are related to war and history, victim-perpetrator paradigm, tourist hotspots, and traditional clothes. More broadly and in terms of economic development, this digital transition in the cultural sector can help to improve the international standing of the Vietnam and provide a way of attracting foreign investment.

Ensuring Sustainable Digital Transition in the Cultural Sector

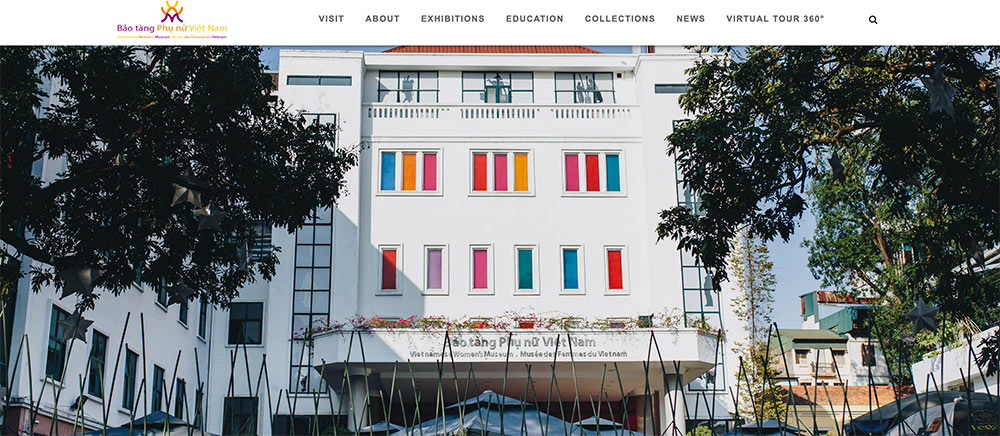

The digitization of artworks and collections has become one of the central aspects of work for cultural professionals in the art and cultural sector in Hanoi. Whilst this digitization of art and culture in Hanoi has been happening for the last 5 years, it has been predominantly for archiving and preservation. It is only now that parts of these digital archives have started to be made publicly accessible. The current transition that is taking place in the art and cultural sector in Hanoi includes the digitization of art collections into digital archives for preservation. State museums and art institutions are carrying out digitization projects, such as VICAS, the Museum of Ethnology, and the Vietnamese Women’s Museum. These national digitization projects focus on the preservation of folk arts and intangible cultural heritage and are supported by the Ministry of Culture, Sport and Tourism. These digitization practices include scanning images, objects and photographs for preservation or in order to create digital archives. However, these digital archives and collections are (mainly) not publicly accessible but, rather, solely for preservation and archiving. For this reason, the link between national cultural institutions working on digitization for archiving and preservation vis-à-vis on public digital access to digitized work and collections is limited.

This suggests a need for more provision of access to artworks and artifacts, in order to make these collections more inclusive and accessible to the public and more engaging and interactive for audiences. It suggests a need to put in place a common set of standards and protocols for the digitization process and digital transition of art and culture in Vietnam that is currently underway. A digital culture policy is required for this in order to ensure best practices are put in place and challenges are addressed.

Today, cultural professionals are beginning to find innovative ways of publicly displaying digitized content by using new digital technologies. This is happening predominantly in non-governmental, independent organisations and art spaces. For instance, there are some initiatives by independent, non-governmental art organisations, whose digitization projects are sponsored by UNESCO, the Goethe Institute, the British Council and the Danish Embassy. Manzi Art Space provides an example of an independent art space that is innovative in its work on the public display of digitized art collections. They are currently experimenting with the use of augmented reality, for instance, with an art project entitled ‘Into Thin Air’. However, some national institutions have begun to utilize new digital technologies. For instance, the Vietnamese Women’s Museum started using YouTube to connect the museum to its audience, with virtual exhibitions, and has begun to create 3D digital models of their art pieces (a digitization project that has been initiated by the author and co-investigators on this research project at RMIT University).

Potential for Digital Development in the Cultural Sector

Vietnam has been moving towards digitization in many areas for the past decade, including government, economy and society. “In the new Vietnam, science, technology and innovation have a critical role to play in furthering Vietnam’s development” (Cameron et al., 2019). It is important for Vietnam to be able to utilize new digital technologies such as Artificial Intelligence (AI), virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR), and interactive, immersive platforms as well as to have access to digital infrastructure such as 3D scanning. However, as the program for national digital transformation (Vietnam Government, 2020) outlines, in order “to sustain high growth, Vietnam will need to overcome substantial challenges”. The primary challenge for policymakers will be to allocate resources and there is also another need to overcome the challenge of human resources and skilled personnel, with the need for collective training and up-skilling – which is the case across the workforce and society – in order to enable a successful digital transformation (Vietnam Government, 2020). The Vietnamese Government outlines key areas of focus: (1) the importance of internationalization in order to open up Vietnam to new markets, for knowledge and skills transfer, and for investment; (2) the need for cybersecurity and privacy; (3) the need to improve digital infrastructure in order to be able to utilize new platforms and apps.

The Vietnam government has outlined a strategy for “national digital transformation by 2025” in order to create socioeconomic development and to allow the country to take an active role in the fourth industrial revolution (Vietnam Government, 2020). The goal is to become a “prosperous digital country that pioneers trying out new technologies” (Vietnam Government, 2020). This transition is important for achieving the nation’s sustainable development goals. 1 The strategy demonstrates priorities in the development of a digital society in order to achieve “digital divide bridging”, especially in terms of access and digital infrastructure, with implementation of fiber optic broadband and 5G network (Vietnam Government, 2020). The strategy also highlights a willingness to push for more international connections, by outlining the objective of establishing digital enterprises that are “capable of going global” (Vietnam Government, 2020). International connections have been identified as a key contributor to digital transformation, with the connection of technology enterprises abroad that can facilitate the “application of new technologies and new models in Vietnam” (Vietnam Government, 2020).

While discussion is taking place on digital culture policy and digitization for preserving cultural heritage in other countries in the region like Malaysia and Singapore (Barker and Beng, 2017; GovTech Singapore, 2020), in Vietnam there is little discussion on digitization strategy and processes nor policy discussion regarding agreement on professional standards and practices for the cultural sector. This is the case even as a lot of art and culture is transitioning to online platforms, transferring to digital formats and the amount of exhibitions online is increasing. While there is policy on digital government, economy and society, there is yet to be a policy on digital culture. Yet, digital culture is important for the cultural preservation and dissemination of Vietnam internationally, to maintain and promote Vietnam’s national identity, to begin to commercialise digitized culture content, and to strengthen international relations.

Systematic protocols and standard practices need to be put in place in order for digitization to be a sustainable solution for preservation and representation of art and culture in Vietnam. As Fanea-Ivanovici argues, “sustainable digitization” is required and certain requirements are necessary for effective digitization (Fanea-Ivanovici, 2018). This is critical in order to avoid or for Vietnam to be lagging behind other countries in the region or globally. This is because many countries globally have put in place a digital culture plans and policies. 2 In addition, within the framework of the UNESCO 2005 Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions, in 2017 participating States adopted the Operational guidelines on the implementation of the Convention in the digital environment; and in 2018 they agreed a roadmap to foster diversity and strengthen the cultural value chain. Fanea-Ivanovici considers the need for open-access archives and museum collections so that audiences can have equal access to digital art and cultural content (Fanea-Ivanovici, 2018). Fanea-Ivanovici argues it is important to discuss this issue in order to ensure a “sustainable and inclusive growth” in the art and cultural sector (Fanea-Ivanovici, 2018) and to ensure more equal representation of art and culture globally.

Challenges in the Digitization Process in Vietnam

The lack of intellectual property and copyright law or digital culture policy is another challenge that respondents mention in relation to challenges and issues with the cultural sector in Hanoi. Many respondents linked to issues with intellectual property and copyright when talking about the current state of the art world in Hanoi. Participant 4 from Quây Son says “copyright is a big problem in Vietnam” and Participant 2 from Phò Dày says there is “no law from government to protect copyright and artists.” Participant 15 from Song Hong also says that “IP and copyright is an issue and concern with Facebook, even though it’s free.”

Many respondents call for an intellectual property law and copyright law to be established and enforced. They see this lack of policy and law as creating another challenge in the digitization process and in impeding their ability to utilize digital platforms, as they do not know what they can publish online and because the copyright and intellectual property system currently is unclear and complicated. In some cases, this makes some decide not to publish artworks online. As Participant 15 from Song Hong says, “there is no policy on digitization”. Participant 18 from Cá also shares that there is a “need for standards and markers for digitization” and a “need for IP”. Participant 18 from Cá says that these are required in order for the cultural sector to develop. Participant 19 from Dong Nai is clear in outlining the importance of creating this policy, by referring to “the importance of a sufficient IP law, or one that is enforced. People need to be educated on how to use art online, how to share and download. It is important to make content accessible but in the right way. There is a need for a policy on digital culture – there is policy on digital society, economy, but not on culture.”

Furthermore, there should be a country-specific and culture-specific policy for digital culture due to the specific nature and structure of the cultural sector in Hanoi. This transition towards digitization will also be specific, thus, requiring a specific ‘digital culture’ policy and adequate intellectual property protection laws online. Whilst many discussions nationally are about policy concerning the preservation of cultural heritage and traditional culture, more consideration is necessary on how to make digitized archives publicly accessible and how to best preserve contemporary culture digitally.

Emma Duester

Lecturer, Communication, School of Communication and Design

RMIT University, Hanoi, Vietnam

References

Barker and Beng, (2017) ‘Making Creative Industries Policy: The Malaysian Case’ in Kajian Malaysia, 35(2), 21-37.

British Council (2018) Cultural and Creative Hubs in Vietnam 2018-2021. Available online at: https://www.britishcouncil.vn/en/programmes/arts/cultural-creative-hubs-vietnam.

Last accessed 23 March 2020.

Cameron A, Pham T H, Atherton J, Nguyen D H, Nguyen T P, Tran S T, Nguyen T N, Trinh H Y & Hajkowicz S (2019). Vietnam’s future digital economy – Towards 2030 and 2045. Brisbane: CSIRO.

DigGov Singapore (2020) Digital Government Blueprint. Available online at: https://www.tech.gov.sg/digital-government-blueprint/ Last accessed 28 April 2021.

Fanea-Ivanovici, M. (2018) ‘Culture as a Prerequisite for Sustainable Development: An Investigation into the Process of Cultural Content Digitisation in Romania’ in Sustainability, Vol. 10, No. 1,

pp.18-59.

Kulesz, O. and Okell, M. (2020) Supporting Culture in the Digital Age. Public Report. Surry Hills, Australia: International Federation of Arts Councils and Cultural Agencies. Available online at: https://ifacca.org/media/filer_public/30/b4/30b47b66-5649-4d11-ba6e-20d59fbac7c5/supporting_culture_in_the_digital_age_-_public_report_-_english.pdf Last accessed: 13th May 2021.

Lim, L. and Lee, H. (2018) ‘Introduction’ and ‘Culture, Digitization, Diversity: Asian Perspectives’ in Routledge Handbook of Cultural and Creative Industries. London and New York: Routledge.

Ly, T. (2016) A Research Paper about Policy and Creative Hubs in Vietnam. Available online at: https://creativeconomy.britishcouncil.org/media/resources/research-paper-about-policy-and-creative-hubs-in-vietnam.pdf. Last accessed 29 March 2020.

Miles I., and Green L. (2008) ‘Hidden Innovation in the Creative Industries’, NESTA report, July. Available online at: file:///C:/Users/v13008/AppData/Local/Packages/Microsoft.MicrosoftEdge_8wekyb3d8bbwe/TempState/Downloads/2008HiddenInnovationInCreativeIndustries%20(1).pdf. Accessed 6 January 2021.

Mori, Y. (2011) ‘The Pitfall Facing the Cool Japan Project: The Transnational Development of the Anime Industry under Post-Fordism’ in International Journal of Japanese Sociology, Vol. 20, No.1, pp. 30-42.

Ngo, L., V. Tran, M. Tran, and Q. Nguyen (2019) ‘A study on relationship between cultural industry and economic growth in Vietnam’ in Management Science Letters 9 (2019), pp. 787-794.

Nguyen, D. et al. (2019) Vietnam’s Future Digital Economy: Towards 2030 and 2045. Brisbane, Australia: Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation.

UNESCO (2019) Creative Cities Network. Available online at: https://en.unesco.org/news/joining-hands-promote-ha-noi-creative-city-and-unesco-creative-cities-network-viet-nam. Accessed 26 May 2020.

Vietnam Government (2013) Statement of the 7th session of 11th Central Committee of Communist Party of Vietnam. Available online at: http://english.tapchicongsan.org.vn/Home/Focus/2013/376/Statement-of-the-7th-session-of-11th-Central-Committee-of-Communist-Party.aspx. Accessed 12 June 2020.

Vietnam government (2017) National action plan: For the implementation of the 2030 sustainable development agenda. Available online at: https://vietnam.un.org/sites/default/files/2020-08/ke%20hoach%20hanh%20dong%20quoc%20gia_04-07-ENG_CHXHCNVN.pdf Last Accessed 28 April 2021.

Vietnam Government (2020) Introducing Program for National Digital Transformation by 2025 with Orientations towards 2030. Available online at: https://vanbanphapluat.co/decision-749-qd-ttg-2020-introducing-program-for-national-digital-transformation Last accessed: 13th May 2021.

Notes:

- The three main areas are: (1) digital government, (2) digital economy and (3) digital society. This means that there is nothing yet on digital culture. For instance, there is a section on making government documents and services publicly available on digital platforms – but this needs to be translated into the culture sector. It instead says that such decisions are devolved to each sector and organisations part of this sector to devise roadmaps for standard, systematic digitization. ↩

- At a provincial level, in 2014 the Quebec Ministry of Culture and Communication adopted its Digital Cultural Plan which includes a vast range of measures designed to help creative actors appropriate new technologies, and to enhance the visibility of cultural content in the digital environment. In Mexico, in late 2017 the Secretary of Culture drew up the country’s Digital Culture Agenda, which focusses on several strategic pillars, including: the cultural and creative industries; skills; preservation; and social participation. Further south in the Americas, for over a decade the Ministry of Culture of Colombia has promoted its Digital Culture Policy, which seeks to foster the creation of digital cultural content throughout the country, among other objectives. Meanwhile, in the United Kingdom in 2018 the Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport (DCMS) launched its Culture is Digital policy paper, which encourages the use of digital tools to drive audience engagement; boost the digital capability of cultural organisations; and unleash the creative potential of technology. Multilateral organisations have also started developing a strategic vision on these topics. Since 2014, the Ibero-American General Secretariat (SEGIB) and the Organization of Ibero-American States (OEI), have coordinated to implement a Digital Cultural Agenda for Ibero-America, which will promote digitisation; society’s participation in digital culture; creative industries; the generation of local and shared content; and the preservation of cultural heritage (Kulesz and Okell, 2020: 8). ↩