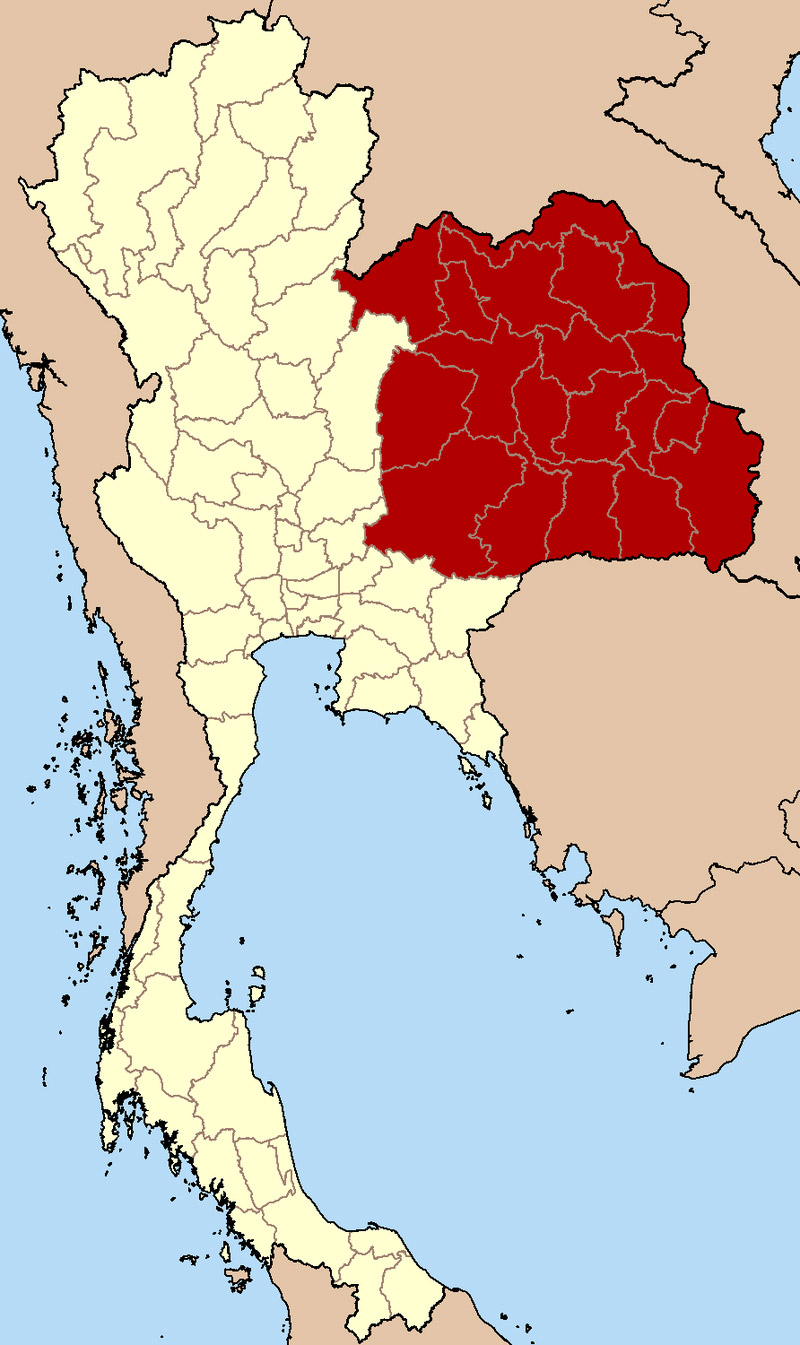

The eerily dull atmosphere of the 2019 elections was a telltale sign that the path towards democracy for the Thailand was still blocked by the same gatekeepers—the junta-backed ruling elite. The Pheu Thai Party, the leading opposition party, won the majority of parliamentary seats but failed to form a government. What do these election results mean for voters in the Northeast region (also known as Isan)? Will the clear signal that junta leader General Prayuth Chan-ocha is determined to stay in power be the start of a rejuvenation of the powerful Redshirt movement that has long been the expression of political frustrations in Isan? In this essay, I attempt to answer the latter question from a perspective of the rank and file of this political movement. I argue that Red identity, and political identity in the Isan more generally, is even more complex in 2019, but it has not developed into an ethnic political movement.

The History of the Redshirts in Thailand’s political landscape

Political conflicts that led to the 2006 coup that ousted controversial Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra bifurcated the country. On one side there was the Yellowshirt movement (formally known as the People’s Alliance for Democracy—PAD) who vehemently disliked Thaksin and his political associates, citing corruption, nepotism, power abuse, and anti-royalism. Most Yellowshirts were middle-class city dwellers who professed their dislike for corrupt politicians and upheld conservative values associated with “Thainess”. They staged a series of protests between 2005 and 2006 aiming to oust Thaksin, a feat achieved with the 2006 coup. On the other side was the Redshirt movement (formally know as the United Front for Democracy Against Dictatorship—UDD), formed around 2007 in response to the coup and the Yellowshirt movement. Redshirt protesters came from a range of socioeconomic backgrounds, but the majority of them came from provinces in the North and the impoverished Northeast (also known as Isan) (Naruemon and McCargo 2011).

In 2014, a military junta led by General Prayuth Chan-ocha removed the government associated with former Prime Minister Yingluck Shinawatra, younger sister of Thaksin. Thailand’s “color-coded” street movements again featured at the heart of politics. The coup was staged using street protests by the People’s Democratic Reform Committee (PDRC)—a coalition of former Yellowshirt protesters, elite supporters, and anti-Shinawatra groups—and counter-protests by the Redshirts as a pretext. Yet, while PDRC leaders were not subject to military harassment in the aftermath of the 2014 coup, Redshirts were harshly suppressed throughout the country (Saowanee and McCargo 2019). Because of the junta’s violent, suppressive measures, the Redshirt movement was essentially paralyzed. In the immediate aftermath of the coup, protests were small and sporadic, mostly organized by university students, academics, or those identifying themselves as neither red nor yellow.

A couple of years after the coup, Redshirts finally began to emerge again, showing their support by attending various political events around the country. At the largest post-coup gathering organized at Thammasat University on July 24, 2016 to examine the draft constitution, a large number of Redshirts assembled, sporting their red clothing and paraphernalia. Redshirt attempts to host activities independently, such as referendum monitoring, however, were not permitted (Saowanee and McCargo 2019). As junta rule progressed, moreover, Redshirt leaders continued to be bombarded with legal charges. Some fled the country while others were arrested, tried in military courts, and imprisoned. From my field research trips during the junta period, I returned with narratives of anger and frustrations. On one occasion, when I was interviewing a group of Redshirt villagers in Ubon Ratchathani, instead of answering my questions, out of the blue one of them asked when someone would step up to be a leader to push the military out. The Redshirts remained relatively quiet but deeply frustrated, waiting for the military’s tight grip to ease.

The Redshirts and the 2019 elections: Growing frustrations

After a series of delays for almost 5 years, finally came the March 2019 general elections. The Redshirts mobilized. As in times past, they appeared in the audience of Pheu Thai mass campaign rallies in the Northeast donning their red UDD shirts. A difference this time was that the party’s key rally speakers did not mention its ties to the movement, though other speakers were not barred from doing so. Local UDD-Pheu Thai leaders talked about the plights of the Redshirts before and after the coup, especially the ordeal the Redshirt leaders went through while being imprisoned—bolstering the “double-standard” grievance that the movement campaigned against during the heyday of its protests. This rhetoric went hand-in-hand with the party’s anti-junta platform, which was well-received by the audiences.

The Redshirts also attended rallies by the anti-junta Pheu Chart Party and disbanded Thai Raksa Chart Party. Pheu Chart’s campaign strategist was UDD Chairperson Jatuporn Promphan. Many Redshirts occupied front seats at rallies in Kalasin Province, reminiscent of their rally days back in 2010. The defunct Thai Raksa Chart, spearheaded by another highly influential UDD leader and orator, Nattawut Saikua, also attracted the interest of the Redshirts. In Roi Et Province on March 13, 2019, after the party was disbanded over a charge of nominating former princess Ubolratana as prime minister candidate, Nattawut Saikua gave a speech urging voters to vote for any party representing democratic, anti-junta values. Here, too, the Redshirts showed up in the front rows cheering the speakers on enthusiastically.

What this shows is that Isan voters no longer identified their “redness” with only Pheu Thai when it comes to electoral politics. They thought they had more choices. Many of them still supported Pheu Thai because they saw the party as a victim of injustice just like they were, fighting side-by-side together since the 2006 coup. 1 That was not at all surprising. As part of an ongoing research project on their political beliefs, I have been interviewing Redshirts after the elections. An interesting finding is that many of them, especially the most ardent protesters, favored Future Forward Party leader Thanathorn Juangroongruangkit’s bold and confrontational style. Some expressed their preference for another anti-junta politician, Police General Seripisut Temiyavet, thinking that only a strongman character was a match for the military authoritarianism that had been ruling the country for years. 2

The elections, as some Redshirts have told me, could not and did not solve the country’s long-standing conflicts. As we have witnessed so far, elections have been part of the problem by allowing more players to be even more visible in exercising their powers for the benefit of the ruling elites. It allowed the continuation of military influence in politics. As the verdict on Thanathorn’s cases are looming near at the time of this writing and the day-to-day economic hardships are growing more serious, there is no guarantee that large-scale street protests will not erupt again. But some Redshirts are more cautious than others, preferring to continue their struggle through the parliamentary system first. However, when asked what they would do if the situation got to the point where parliament could no longer function, most of them said, “ja ok maa” [will come out], meaning they are still willing to take to the streets and join demonstrations.

Thus, although Redshirt activists today may not necessarily have their “red’ shirts on, they have internalized their political experiences and beliefs. Despite experiencing harsh suppression and witnessing the plight and demise of their leaders or fellow activists, these ordinary, aging protesters are still engaged in politics by closely monitoring the news and staying in touch with their smaller, close-knit groups waiting for an opportunity to show their “redness”. We do not know what that opportunity will look like and how exactly these activists will express their “red” ideology. All we know is that the movement is still in the game, dormant but not dead.

Redshirt Identity and Isan Identity

Over time, the Redshirt movement has come to be particularly associated with the country’s most populous region, the Isan. However, this does not mean that the Redshirt movement is an ethnic movement. First, there are Redshirts in all regions of Thailand, including the opposition stronghold of the South. Second, not all people living in Isan are Redshirts. So, what is the relationship between Isan identity and the Redshirt movement?

As I have written elsewhere, the Redshirt movement was not entirely uniform (Saowanee and McCargo 2016, 2019; Saowanee 2018). The main organization leading the Redshirt coalition was the United Front for Democracy against Dictatorship (UDD), but it was not the only Redshirt organization. Indeed, there were different factions in the movement, but all of them claimed to support democracy. Not all Redshirts supported Thaksin (some even despised him). Conversely, there were people who always voted PT and liked Thaksin but never joined any Redshirt rallies and still called themselves “red”.

In addition, there were other non-Redshirt movements in Isan. These tended to be based on causes other than “politics” per se, such as the Assembly of the Poor. In the past, protest groups often avoided labeling their cause “political” due to the deeply rooted view in Thai society that “politics is bad”. The Redshirt movement, however, embraced its identity as a “political movement”. This has led some of these other movements to distance themselves from a Redshirt identity. 3 At their recent protests in October 2019 in Bangkok, some Assembly of the Poor protesters vocalized their frustrations of not wanting to be associated with electoral politics, fearing that the government would use such association to accuse them of having a manipulator from behind the scene (e.g., Thaksin)

More generally, the “red” identity carries with it some risk and social stigma. Many people fear being persecuted if they openly admit they are red because of some of the perceived attributes such as anti-monarchy, anti-junta, etc. Many formerly ardent protesters are reluctant to say they are “red” even though they voted for Pheu Thai.

What this implies is that “red” identity, although perhaps the most dominant, cannot be characterized as the identity of the Isan region, or the Isan people. It is unlikely that this region would be a location for an ethnicity-based civil war, as some observers have argued. While ethnic identity is present, it is not strong enough to become a driving force for separatism. The Lao identity has been successfully assimilated and transformed into Thailand’s regional identity (Saowanee and McCargo 2014; Ricks 2019).

This is not to say that the Redshirt movement doesn’t express frustrations held generally by the people of the region. The belief that the Isan people are legitimate voters/citizens of the country is strong and has become the main drive for them to take part in politics, both Redshirts and non-Redshirt. Both Redshirts and non-Redshirt Isan people see inequality as a big problem in Thailand, and feel that the Isan region has been neglected and exploited rather than developed. Isan people have thus been struggling to tell the state to listen to them in various causes even before the birth of the Redshirts. What the Redshirt movement shares with the political culture of the Isan region is mostly a desire for inclusion and development (see Saowanee 2019b). As such, we have not seen Redshirt organizations from Isan turn to ethnic rhetoric or goals of separatism.

Saowanee T. Alexander

Ubon Ratchathani University, Thailand

References:

Saowanee T. Alexander & McCargo, D. 2016, ‘War of words: Isan redshirt activists and discourses of Thai democracy’, South East Asia Research, vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 222-241.

Naruemon Thabchumpon & McCargo, D. 2011, ‘Urbanized villagers in the 2010 Thai Redshirt protests: Not just poor farmers?’, Asian Survey, vol. 51, no. 6, pp. 993-1018.

Saowanee T. Alexander, 2018, ‘Red Bangkok? Exploring political struggles in the Thai capital’, Critical Asian Studies, vol. 50, no. 4, pp. 647-653.

Saowanee T. Alexander, 2019b, ‘Isan; Double trouble’, Contemporary Southeast Asia, vol. 41, no. 2, pp. 183-189.

Saowanee T. Alexander & McCargo, D. 2019, ‘Exit, voice, (dis)loyalty: Northeast Thailand after the 2014 coup’, in MM Montesano, T Chong, M Heng (eds.), After the coup: The National Council for Peace and Order era and the future of Thailand, ISEAS, Singapore, pp. 90-113.

Notes:

- Saowanee T. Alexander, 2019a, ‘Cooptation doesn’t work: How redshirts voted in Isan’, New Mandala, 10 April, viewed 16 October 2019, https://www.newmandala.org/cooptation-doesnt-work-how-redshirts-voted-in-isan/. ↩

- However, judging from their outward appearances, no Redshirts attended Future Forward rallies, although some did attend at least the rally in Ubon Ratchathani Province. This suggests that for whatever reason these Redshirts did not want to display their identity at Future Forward Party rallies. The reason behind this is worth investigating, but suggests that there is a degree of reservation among the Redshirts in openly supporting Future Forward Party. ↩

- Ironically, activists such as the Assembly for the Poor, have many similarities to the Redshirt movement in terms of their goals. There have always been a multitude of groups in Isan protesting against state-initiated mega projects before the Redshirts also began talking about inequality and unfairness. ↩