The Cold War left a dramatic mark on Malaysian politics and society. The anti-communist Emergency of 1948–60 demonstrated the lengths to which first British colonial, then local, elites were prepared to go to combat communism’s advance domestically. But the still-pervasive threat of communism, then the specter of an all-too-convenient communist bogey, resonated across the polity well beyond the marginalization, then defeat, of the Malayan Communist Party (MCP). The Cold War left a complex and enduring legacy for Malaysian formal politics and civil society. We can see these implications still in terms of political ideologies, settlement patterns, restrictive legislation, and geopolitical positioning. Overall, Malaysia did experience a genuine, and genuinely aggressive, communist movement, and its counterinsurgency measures, coupling a hearts-and-minds strategy with military suppression, remain a benchmark for countering violent extremism among security forces today. But what has left a deeper stain is less the Malayan Communist Party per se than how these battles sculpted the ideological, demographic, legal, and security landscape: a largely Chinese, internationally vilified, anticapitalist movement at a formative period in Malaysian sociopolitical development helped to delegitimate ideological alternatives and bolster a strong, centralized, specifically communal and capitalist state, nested in a significantly depoliticized society.

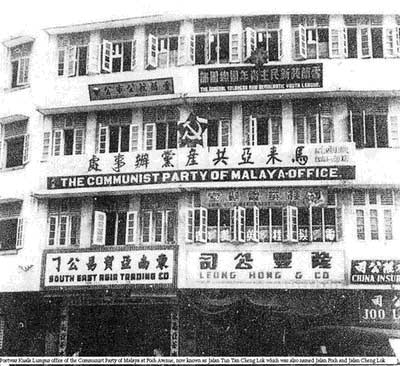

Malaysia offers a particularly interesting case to consider. On the one hand, its 2018 general elections, in which a largely programmatic coalition ousted a more explicitly patronage-oriented one after 61 years in power, but an Islamist third party also made a strong showing, signal the still-significant pull of ideological rather than merely transactional or technocratic politics. On the other hand, that political mapping also reflects the long-term history of suppression of left-wing movements: Malaysia has not had a strongly (or at least, overtly) class-based political alternative, beyond a small, beleaguered Socialist Party, in decades, notwithstanding its early history of active, popular left-wing politics. That the MCP, including its armed wing (the Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Army, MPAJA, then the post-war Malayan People’s Liberation Army, MPLA), sparked a traumatic anticommunist guerilla war just as the now-Malaysian state was taking shape proved pivotal to the shape and character of that state, from restrictions on sociopolitical organizations (especially those on the left), to downplaying the Chinese role in Malaysian political development, to constraining the range of ideological perspectives generally deemed legitimate.

Cold War Residues

The Malaysian state would appear no longer to have faced an appreciable threat of communism after the Emergency wound down, even though the MCP fully surrendered only in 1989. But especially with the Cold War (and within Southeast Asia specifically, the Vietnam War still raging), the communal, pro-capitalist late 1960s/early 1970s state faced minimal pushback in quashing its then-key challenger, a cross-racial Socialist Front, as both leftist and Chinese-dominated, with “Chinese” read as “communist.” Indeed, communism as specter still provides, a useful foil to legitimate a strong state and a concertedly depoliticized society. The Cold War’s legacy thus lives on in Malaysia, effectively crystallizing domestic rivalries. That durable residue is particularly clear in terms of political ideologies, settlement patterns, restrictive legislation, and Malaysia’s geopolitical positioning.

Ideological Space

Anticommunist ideology contributed to British and Malayan efforts to suppress radical trade unions and class-based alignments, helping to entrench instead ethnic pillarization and communal politics. That outcome specifically reflected the interests of elites in UMNO and its Chinese and Indian partners in the Alliance, then Barisan Nasional (National Front). Their model of political affiliation and administration depended on voters’ primary axis of identification’s being along lines of ethnicity, not class—and from the outset, the Alliance/BN supported a capitalist economic model, supplemented by pro-Bumiputera (Malay and other indigenous) redistributive policies.

The logic of the Cold War allowed British and Malayan elites to press ideological embrace of capitalism not as in their own interest, but as warranted by existential threat. In those early days, the mass of Malays were small-scale rice farmers, sustained in that role by British policy and presumably agnostic at best toward capitalism. But the community’s dominant elites were securely invested in the order the British wrought. British policies sought to establish a Malay agricultural middle (and capitalist) class, while creation of a Malay administrative service and other ethnically targeted efforts expanded that integration into the British polity.

Most Chinese economic elites were equally embroiled in capitalist pursuits. But rather than small-scale farmers, more of the Chinese (and Indian) working class constituted an emerging industrial proletariat, in factories as well as rubber plantations, tin mines, and paid labor such as dock-work. It was from among this base in Malaya and Singapore that left-leaning trade unions emerged, presenting critical perspectives on (Western-dominated) capitalism. Trade unions served as potential or actual launching pads for critical, partisan political engagement, facilitating not only class- rather than ethnic-identification, but also collective action. Ideologically denigrated or simply repressed early on, labor remains largely quiet now. And while the early years after independence saw left-wing parties making real headway, especially at the local-government level, early suppression and disincentives have left no party that serves as the acknowledged workers’ party.

Importantly, formal politics retains limited tolerance for critical engagement. Even so, long beyond the MCP’s demise, one may still be branded as “communist,” as a catch-all delegitimation, nor is the state’s ethnocentric spin on neoliberalism, inclusive of extensive preferential policies, presented as “ideological”; rather, dominant political discourse frames Malay supremacy as demographically and sociologically inevitable and rarely considers seriously alternative economic frameworks. All told, the patterns the Cold War entrenched, of communal rather than class alignments, of eschewing consideration of socialist or social-democratic models, and of deeming Chinese citizens intrinsically suspect, have enduringly colored post-Cold War ideological possibilities and praxis.

Population Resettlement

The Cold War’s second key legacy in Malaysia concerns the human landscape itself. Emergency-era anticommunist efforts extended to the forcible resettlement of over a half-million ethnic Chinese, about one-tenth the population at the time, into what were euphemistically called “New Villages,” as a (punitive) prophylactic effort intended to disrupt MCP supply chains.

However concentrated in cities and around mining sites, some share of ethnic Chinese had long occupied subsistence farms; the Japanese occupation in the 1940s increased that rural dispersion, with as many as 500,000 Chinese squatters in settlements along the fringes of the jungle by 1945. These communities supplied the MPAJA with food and other supplies, conduits for information, and recruits, willingly or not (Tilman 1966, 410, Yao 2016). Colonial authorities assumed MPAJA troops could not survive long in the jungle without such provisions, so moved communities wholesale into fenced-in villages. Integration into the political mainstream was part of the effort, primarily via the Malayan Chinese Association (MCA), which supplied amenities and helped New Villagers adapt to their new environment (see Teh 2007 [1971]).

But resettlement left both MCP sympathizers and others geographically isolated in monoethnic towns and, in many cases, deeply dissatisfied with so intrusive a state. Mass displacement heightened ethnic identification, including carving out a clear niche for the MCA as communal protector. The initiative also sparked new forms of local governance, including introduction of representative structures designed to increase residents’ sense of investment in their new communities (Strauch 1981, 40-41), and fostered new techniques and justifications for surveillance.

New Villages remain scattered across especially western peninsular Malaysia. They may be less ethnically mixed than more organically formed cities and towns. And they have been inconsistently served, at best. Although most had basically adequate infrastructure by the mid-1980s, the settlements have faced overcrowding and scarce agricultural land; limited employment opportunities and, hence, outmigration; poor or limited schools and other amenities; and inadequate administration and fiscal resources (Rumley and Yiftachel 1993, 61-2). All told, the extent of population reconfiguration Cold War anticommunism inspired represents an enduring and consequential legacy of the period.

Legal Curbs

Third, we turn to the legal landscape. Unlike elsewhere in the region, anticommunist efforts did not elevate the armed forces per se, notwithstanding protracted military engagement. In retrospect, that restraint is fairly remarkable. However, the Emergency saw new curbs on civil liberties and sociopolitical reorganization that persisted even beyond the Cold War. Not just labor-related, but also other civil-society organizations have remained subject to rules on registration and official scrutiny dating back to Emergency regulations. Moreover, the norm of requiring special police powers to interdict loosely defined, including specifically political, threats persists, as a holdover from Cold War-era efforts.

More insidiously, this sociolegal apparatus helped to entrench devaluation of critical political engagement as daring, reckless, or simply inappropriate—and specifically to encode an assumption of Chinese Malaysians as perhaps unreliably loyal. The key developments that served to entrench this view were urban Malay–Chinese racial riots in the late 1960s, especially in Kuala Lumpur after the May 1969 elections. Over time, though, the dominant reading of “May 13th” shifted, erasing the ideological cast of rebuking an ascendant Socialist Front in favor of a purely racialized depiction: new enactments after a period of emergency rule from 1969–71, complementing the NEP, rendered verboten any attack on, or even critical discussion of, Malay special rights.

Still today—and thus far persisting, notwithstanding the first change of government since independence—Malaysia has a set of legal constraints clearly out of proportion with any actual threat. While it lasted, the Cold War offered a handy specter, not too really present, but conveniently aligned with local power struggles and prejudice, to justify measures otherwise objectively unduly coercive. Decades on, that legacy remains.

External Relations

Lastly, as sociopolitical patterns crystallized in Malaysia, prosecution of the Cold War elsewhere in Asia buffered the polity from external intervention or even sharp critique. Western powers tolerated illiberal leadership in Malaysia and other regional states, so long as those partners opposed communism themselves (and through the 1970s, especially if they facilitated military access to Vietnam). As such, Malaysia enjoyed protection from uncomfortable conditionality or external pressure.

What is not clear is the extent to which, and why, these allowances became habit: beyond Vietnam, beyond even the fall of the Soviet Union, the US and other democracies continued to accept an increasingly repressive Malaysian state, so long as it remained a useful trading partner. American policymakers grumble at the scope of preferential policies, but Malaysia still seems to benefit from a laissez-faire approach, with rapprochement premised overwhelmingly on shared economic interests and approaches. Malaysia has aligned neatly enough ideologically with anticommunist external powers to be non-threatening, and, hence, largely unchallenged.

In short, Malaysia has enjoyed wide leeway since its Cold War-era birth, especially once ASEAN had taken shape and offered an additional buffer against presumed-creeping militant communism. That experience would seem to offer a lens on the scope of the Cold War as an international conflict: prosecuting it entailed shutting off, coopting, or containing challenges internally before they could find ideological allies abroad or otherwise graduate from domestic to transnational.

Conclusion

The end result of these processes has been long-term fortification of an electoral-authoritarian regime that is only now in the early, uncertain stages of formal transition. That regime privileges communal identities, reinforced by enduring settlement patterns. It also privileges capitalist development, with welfare support couched as gifts from a benevolent regime rather than entitlements due citizens, and a widespread, deeply internalized, only intermittently sidestepped discouragement of critical engagement with politics. Parts of this legacy are no doubt to be found across the region, but Malaysia’s substantially bloodless, phased decolonization from Britain, its communal framework, and its developmentalist ambitions and efforts spin these legacies in particular, and consequential, directions.

It remains open to debate how much threat the MCP ever actually posed in Malaya: whether the polity could really have gone communist. Clearly, the MCP’s armed wing was well-structured and fairly potent, but the organized political left was largely noncommunist and itself significantly communally stratified. What is more clear is the extent to which communism did not need to win to leave an irrevocable, deep mark on the polity, shaping its institutional, ideological, social, and strategic paths in key ways in the years and decades ahead.

Meredith L. Weiss

Professor, Department of Political Science, University at Albany, SUNY

Banner: View of the National Monument of Malaysia located in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Image: EQRoy / Shutterstock.com

References

Rumley, Dennis, and Oren Yiftachel. 1993. “The Political Geography of the Control of Minorities.” Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie 84 (1):51-64.

Strauch, Judith. 1981. Chinese Village Politics in the Malaysian State. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Teh, Hock Heng. 2007 [1971]. “Revisiting Our Roots: New Villages.” The Guardian 4:3.

Tilman, Robert O. 1966. “The Non-Lessons of the Malayan Emergency.” Asian Survey 6 (8):407-19.

Yao, Souchou. 2016. The Malayan Emergency: Essays on a Small, Distant War. Copenhagen: NIAS Press.