Democracy’s durability (and desirability) is a topic of debate worldwide, and the conversation is no less contentious in Southeast Asia. It is, of course, a region that has experienced numerous transitions toward and away from democratic practice in recent years. New research on Myanmar’s recent political evolution provides some novel insights on transitions. These insights can be used to see how similar dynamics played out during Indonesia’s reformasi period, and could potentially occur during hypothetical transitions in Thailand and Vietnam.

One particularly thorny problem in transitions to democracy from any kind of authoritarian rule is what to do with the exiting authorities. In the context of a personalistic regime, the answer is relatively straightforward: exile or confine the former leader, purge critical positions of loyalists and generally clean house. Undoubtedly, the success of this strategy relies to some extent on the influence of the incoming government relative to the former leadership.

An outgoing military regime complicates the scenario. Although top leaders may step down, a new democratically-elected government typically relies on the military for national security. Unless the new regime comes with its own army, most of the military will be sticking around. Given their enduring influence, outgoing military regimes can often negotiate their own withdrawal.

In the case of Myanmar’s recent transition, the military (known as the Tatmadaw) insisted on a constitutional arrangement that preserved a substantial number of legislative seats and an effective constitutional veto going forward. They also maintained ownership of businesses in a number of important and profitable industries, such as mobile telephony and beer. Perhaps most importantly, the Tatmadaw maintained their command structure, nationwide presence and coercive power. This has allowed them to strategically use violence to protect rents and political influence. One particularly valuable—and conflict-linked—sector is jade mining and export.

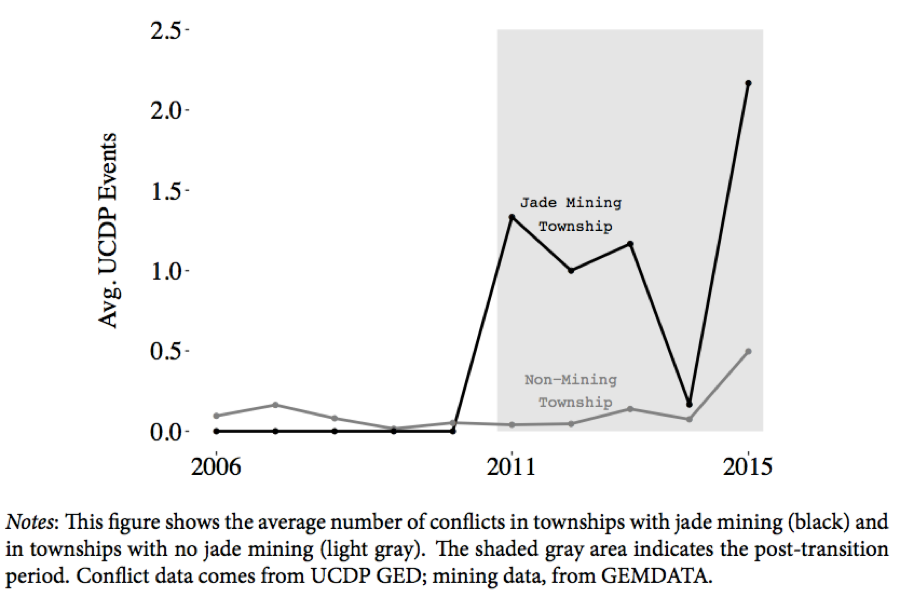

In a forthcoming paper in World Politics, Darin Christensen, Mai Nguyen and I document a surge in Tatamadaw-initiated violence in jade mining areas around Myanmar after the transition to civilian (and later, democratic) governance. We find that the military used violence in places where they had previously jointly extracted jade with rebel groups. This violence served to deter the new civilian government from exerting control of the industry and its revenues. In the article we test a range of alternative explanations, finding that strategic violence by the Tatmadaw is the account most consistent with the data. The following chart illustrates the main empirical finding. 1

Jade Mining and Conflict in Myanmar 2006-2015

The critical take-away from the study is that in countries where there are valuable rents that co-occur with pre-existing anti-government groups, a military can plausibly stoke violence to control or protect those rents in the face of a transition to democracy.

How does this apply more broadly within ASEAN?

Thailand

As Thailand gingerly endeavors to bring democratic practice back into politics, uncertainty regarding the post-transition role for the military is important. Similar to Myanmar, the Thai military have reserved substantial space in politics by establishing an appointed 250-person Senate whose members have an equal say in government formation as the 500-strong elected House of Representatives. This gives the military-affiliated party a major leg up in the electoral process; this is in addition to any electoral manipulation or generic incumbency advantage they may be able to muster.

It appears, at present, that the results of the 2019 general election are set to return the Thai military party Palang Pracharath to power, given the Senate buffer. For now, at least, a full transition to democracy is unlikely. Imagine, however, a situation in which the military (somewhat unexpectedly) lost decisively and chose to hand power over to a civilian, democratic administration.

It appears, at present, that the results of the 2019 general election are set to return the Thai military party Palang Pracharath to power, given the Senate buffer. For now, at least, a full transition to democracy is unlikely. Imagine, however, a situation in which the military (somewhat unexpectedly) lost decisively and chose to hand power over to a civilian, democratic administration.

The ongoing Malay Muslim insurgency in Thailand’s deep south, or any post-election protests, could be used to justify violence that either prolongs their administration or forces more extensive economic concessions. At issue would be stakes and positions of power in the country’s 56 state-owned enterprises. Members of the military already sit on the governing boards of the most important SOEs, “including national oil, telecom, tobacco, airline, railway and pharmaceutical companies. This tactic of fomenting violence would not be new as the Thai military have used unrest in the past to justify dramatic action, including the coups of 2006 and 2014. Stoking violence in the south or elsewhere could provide a similar pretext in the event of a transition.

Indonesia

Looking back to Indonesia’s post-Suharto transition, it remains notable the extent to which the military reduced its formal role in politics after having been so closely involved. For decades, twenty percent of seats in the parliament were reserved for the armed forces, which was reduced during the early reformasi days and eventually eliminated in 2002. The army played a major role in the ‘New Order’ regime, with military personnel serving in civilian government posts as well as political roles.

Ongoing conflicts in East Timor and Aceh at the time of transition provided an opportunity for strategic violence by the army in ways that mimic the Myanmar case. In particular, renewed army offensives during 2001-2002 in Aceh have been attributed by some observers to vested military interests in the black and gray economy, including natural resources, commercial agriculture, weapons and drugs. Long relying on “non-budgetary sources of income,” the Indonesia military in Aceh were loath to end a conflict that would require their withdrawal, especially as professional opportunities were drying up nationwide. This problem continues to the modern day – with major internal conflicts resolved and civilian space still reduced, the question remains of what to do with ‘surplus colonels.’

Vietnam

As a final comparative (and speculative) case, Vietnam provides an intriguing contrast to Myanmar, Thailand and Indonesia. Although the Vietnam People’s Army (VPA) continues to hold a privileged position in society, including numerous economics advantages, since 2001 it has been more firmly subordinate to the civilian leadership of the Communist Party. VPA representation on the Politburo since 2001 has fallen to half of what it was in the preceding decades.

The military continues to hold a great deal of economic power, however, controlling dozens of businesses, including the Viettel mobile operator (which has subsidiaries in ten countries), electronics import/export, real estate and a football team. Although that power has eroded somewhat, the VPA is estimated to own more than 80 enterprises.

In the event of a transition to democracy, the VPA would be hard-pressed to use strategic violence of the kind described above to protect its political and economic benefits, because their earnings are not dependent on control of particular territory and there is no existing insurgency to exploit.

However, Vietnam’s ongoing marine territorial disputes within the South China Sea could be stoked to generate national sympathy for the institution if central decision-makers attempted to take back critical military-owned enterprises. At the same time, if non-defense businesses are removed from the VPA portfolio, it would be in their interest to ratchet up tensions with China to justify greater defense spending and acquisitions, well known to be a lucrative business. This suggests an interstate corollary to the Myanmar conflict dynamic – the well-known tactic of fueling external clashes to protect one’s position back home.

To conclude

Where militaries have attained advantaged positions in politics and business, it is challenging to dislodge them. With a legal claim to the use of violence and the means to carry it out, armies can protect illegitimate or questionable economic positions through seemingly legitimate violent actions. Although many transitions account for military interests in the successor regime, few are effective at curbing the perverse incentives that militaries experience.

Renard Sexton

Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science, Emory University

Visit Renard Sexton’s research website: www.renardsexton.com/research

Thanks to Mai Nguyen for greatly helpful feedback.

Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia, Issue 26, Trendsetters, October 2019

References

Christensen, D., Nguyen, M., & Sexton, R. (2019) Strategic Violence during Democratization: Evidence from Myanmar. World Politics, 1-35.

Kingsbury, D., & McCulloch, L. (2006). Military business in Aceh. (in) Verandah of violence: The background to the Aceh problem, 199-224.

McCargo, D. (2015). Tearing apart the land: Islam and legitimacy in Southern Thailand. Cornell University Press.

Rabasa, A., & Haseman, J. (2002). The military and democracy in Indonesia: challenges, politics, and power. Rand Corporation.

Thayer, C. (2012). Military politics in contemporary Vietnam. in The Political Resurgence of the Military in Southeast Asia: Conflict and Leadership (ed. J.D. London). Routledge.

Notes:

- Image courtesy of the authors (pre-print of Figure 2 in Christensen, Nguyen and Sexton (2019). ↩