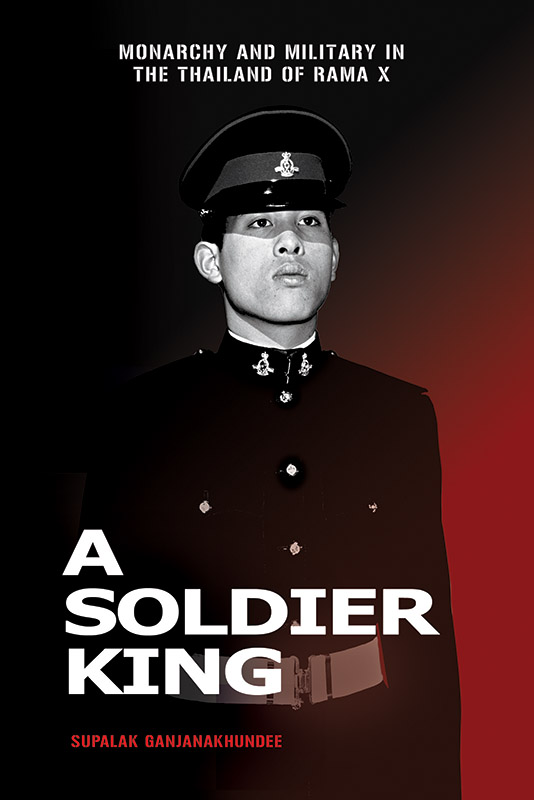

Title: A Soldier King: Monarchy and Military in the Thailand of Rama X

Author: Supalak Ganjanakhundee

Singapore: ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, 2022

In the late nineteenth century, Thailand’s King Chulalongkorn Rama V (1868-1910) undertook reforms that laid the groundwork for a professional military. He introduced Western training, a salaried workforce, and importantly, a ministry responsible for administering a consolidated defence budget. The reforms, that also included replacing a Privy Purse under palace control with a Western-style finance office were to intended to create a modern bureaucratic state. In the twenty-first century, under Thailand’s current King Vajiralongkorn Rama X (2016- ), we are witnessing something remarkable: the re-establishment of overt patrimonialism. By establishing a well-funded private army responsible to him alone, Vajiralongkorn has assumed direct and personalised control of a significant portion of the Thai armed forces, thereby bypassing the government’s own bureaucratic structures.

Supalak Ganjanakhundee’s new book, ‘A Soldier King: Monarchy and Military in the Thailand of Rama X’, is an important and substantial contribution to documenting how Thailand’s new monarch is reviving practices of absolutist rule. He explains how a monarchised military, having sponsored a Cold War revival of royalism in order to oppose communism and legitimize its own rule, is increasingly subject to the whims and caprices of single individual. As Claudio Sopranzetti makes clear in a forthcoming essay (Rama X, Yale University Press), this is a relationship marked far more by fear than by love.

Supalak Ganjanakhundee’s new book, ‘A Soldier King: Monarchy and Military in the Thailand of Rama X’, is an important and substantial contribution to documenting how Thailand’s new monarch is reviving practices of absolutist rule. He explains how a monarchised military, having sponsored a Cold War revival of royalism in order to oppose communism and legitimize its own rule, is increasingly subject to the whims and caprices of single individual. As Claudio Sopranzetti makes clear in a forthcoming essay (Rama X, Yale University Press), this is a relationship marked far more by fear than by love.

Supalak sets out why and how the military-monarchy relationship has changed so significantly since the reign of Bhumibol Rama IX (1946-2016). First, Vajiralongkorn is, by virtue of education and training, a professional military officer. He completed officer training at Australia’s Royal Military College Duntroon, held command positions such as in the King’s Guard, undertook further overseas military training, and even briefly saw action against Thailand’s communist insurgency in the 1970s. All of this makes Vajiralongkorn quite unlike his predecessor Bhumibol, who studied law and was interested in science, and more like earlier monarchs, such as Vajiravudh (Rama VI 1910-1925) and Prajadhipok (Rama VII 1925-1935).

Second, this professional background, combined with personal inclinations that include a notable disinterest in democratic process, is facilitating a significant impact on the Thai armed forces. The establishment of Vajiralongkorn’s private force, the Royal Security Command, including by incorporating two King’s Guard units formerly under the Thai army command, is an important development. Then there is also Vajiralongkorn’s edicts with regard to professional military training. Supalak (p. 84) details how Vajiralongkorn has distributed a handbook to service academies setting out his training philosophy, including that of “simmering”, whereby the art of training soldiers is compared to cooking khai pulo [boiled eggs in sweet brown sauce]. Finally there is Vajiralongkorn’s establishment of a new cadre of officers, the so-called kho daeng or “red-rim soldiers” [because they wear t-shirts with red collars]. These officers graduate from a special three month course in which they commit to the ratchasawat, a code of conduct for those in royal service revived from the era of the absolute monarchy.

Third, the promotion of this new cadre into key positions is changing the institutional underpinnings of the military-monarchy relationship. Under Rama IX, the monarch mediated his relationship to the military primarily through the Privy Council, a handpicked circle of advisers to the monarch. For many years, Bhumibol ensured a compliant military by promoting only those officers deemed suitable by confidante Prem Tinasulanond, the President of Privy Council. Vajiralongkorn has now largely sidelined the Privy Council, assigning it to community and royally-initiated projects. Now he has his own network, comprised of officers who he has known professionally as well as those newly-minted by the kho daeng process.

When combined with Vajiralongkorn’s proclivity for fast-tracking the promotion of members of the royal family and promoting those close to him ahead of other well-qualified candidates, these changes come with a risk of engendering serious disaffection. Supalak (p. 80) tells us of the resistance of some police officers to transferring to his Royal Police Guard, choosing instead to resign or accept punishment in the form of assignment to dangerous posts in the three southern border provinces. Accordingly, Vajiralongkorn’s assumption of control of all Bangkok-based military units can be read as an insurance policy against a coup by soldiers not within his circle of favourites.

This book has many strengths. Supalak has gained access to retired generals such as 2006 coup-leaders Sonthi Boonyarataglin, and progressive Pongsakorn Rodchompoo, as well as others unwilling to be named. In addition to his analysis of changes under Rama X, Supalak weaves the story of the Thai military’s factions and incipient leadership (including the triumvirate of today’s post-junta government Anupong Paochinda, Pravit Wongsuwan and Prayuth Chan-ocha) into an account of the political contestation that paralysed Thailand between the coups of 2006 and 2014. The book is a very useful resource on matters such as distribution of king’s guard units across the Thai military, and recent military promotions, analysed according to army factional alignment (especially with respect to officers associated with the Queen’s Guard or Eastern Tigers, and the King’s Guard or Wongthewan).

There are also some weaknesses. As Supalak himself makes clear (p. 11), the book does not advance a new argument about the Thai monarchy, and instead employs well-known concepts such as McCargo’s “network monarchy” and Chambers’ “monarchized military”. While borrowing in itself is not a flaw, the absence of an overarching thesis to unite the various chapters and sections does lend the book a slightly disjointed feel. Because of this, the book will not necessarily be an easy read for those previously unacquainted with the Thai military and Thai politics more generally. One further area this reader would have liked to have seen developed is with regards to Thai military factions. While the book is assiduous in documenting these, it is not clear what analytical work “factions” perform in terms of explaining the behaviour of the Thai armed forces, nor is it clear how the new Rama X system of favourites will interact with the old factions.

But these are small quibbles. Supalak Ganjanakhundee has given us a thoroughly-researched, lucidly-written and genuinely brave book that will not endear him to Thailand’s powerful establishment. It is a book that needed to be written and should be read, if we are to understand the conservative forces standing in the way of a Thai system of government in which the armed forces are accountable to those that pay for them.

Gregory Raymond

Lecturer, Strategic and Defence Studies Centre, Coral Bell School of Asia Pacific Affairs, ANU College of Asia & the Pacific, The Australian National University