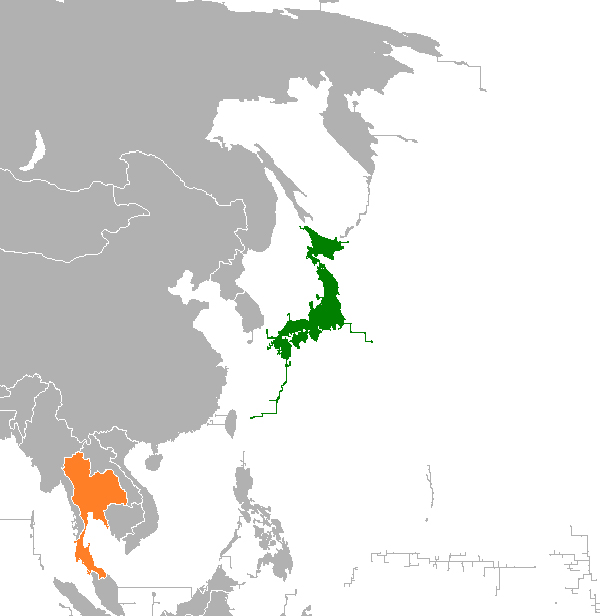

In Thailand, flags were flown half-staff following the murder of former Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. The Thai prime minister, General Prayuth Chan-o-cha, who first came to the premiership after his coup in 2014, also posted a condolence message on his Facebook page. It referred to Abe as “Japan’s favorite son” who had made “his beloved Japan and the world a better place”. And despite the tilt of his government towards the People’s Republic of China (PRC), he also referred to Abe as a “great friend”. But General Prayuth was not the only Thai premier to post a public condolence message stressing the personal relationship with the murdered former Japanese prime minister and offering an exuberant assessment of the latter. From exile, deposed former Prime Minister Yingluck Shinawatra wrote of the “visionary leadership that empowered Japan to recover from economic hardship” while also mentioning that she met and consulted with Abe several times while in office. Her likewise deposed and exiled elder brother Thaksin called Abe a “savior who revived and strengthen[ed the] Japanese economy”.

These messages across partisan lines reflect of course longstanding good bilateral relations, and the importance accorded to Japanese investment by the governments of all three prime ministers. Yet, given the degree of political polarization in Thailand, the glowing assessment of Japan’s longest serving prime minister across party lines is striking.

A Trusted Friend: Japan and Thailand before Shinzo Abe’s Premiership

What certainly contributed to the wording of the messages was that Japan is seen very positively by the Thai public across the political divide due to the history of Japanese-Thai relations. More than 90% of the respondents of a 2021 survey considered Japan as a trustworthy partner of Thailand (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan 2022).

Modern diplomatic relations were already established in 1887, much earlier than between Japan and other countries in Southeast Asia, as Thailand was also never formally colonized. Since the reign of King Chulalongkorn (r. 1868–1910) a small number of Japanese were hired by Thai governments while some Thais studied or trained in Japan. During World War II, both countries entered into a military alliance. One important legacy of the alliance is that forced labor and sexual slavery do not overshadow Japan’s relations with Thailand in the present. And consequently, Shinzo Abe’s revisionist historical views received little coverage in Thailand. After the WWII, Japanese-Thai relations were quickly rekindled. Japanese overseas development aid to Thailand began in the 1950s, and Japanese investment poured into the country. The lowest point of the bilateral relations was reached in 1972, when students organized a boycott of Japanese goods to protest against the dominant position that Japanese companies had acquired in the Thai economy. A public diplomacy campaign supported by the Japanese Foundation is credited for overcoming this crisis. But the massive inflow of Japanese investment after the Plaza Accord, creating jobs and contributing to raising standards of living played an at least as important role. Japanese investment also contributed in Thailand becoming a middle-income country in 2011.

Universal Values and Thai Coups

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, the governments of Prime Ministers Thaksin Shinawatra and Junichiro Koizumi began to negotiate a free trade agreement to further boost the economic relationship. But before the Japanese-Thai free trade agreement could formally be concluded, Thaksin Shinawatra was ousted by a coup on 19 September 2006. Shinzo Abe became prime minister for the first time the following week. The coup posed a challenge for the first Abe government. How to engage with the junta was a question of principle. But the military government also posed a threat to the free trade agreement, as it was widely seen as a Thaksin policy, and therefore rejected by one faction of the anti-Thaksin protestors. It took behind the scenes maneuvering through personal contacts and the invitation to Japan of the coup-installed Prime Minister General Surayud Chulanont to see the agreement formally concluded during the latter’s visit to Japan in April 2007 (Kobayashi 2010, 114–129).

Prior to the visit, in November 2006, a new, value oriented foreign policy had been unveiled. The Arch of Freedom and Prosperity emphasized democracy, freedom, the rule of law, human rights, in addition to the market economy. Abe’s August 2007 speech in the Indian parliament on the Confluence of the Two Seas which introduced the Indo-Pacific into geopolitical discourse explicitly referenced the Arch. The Joint Statement at the signing of the Japanese-Thai free trade agreement, named an Economic Partnership, explicitly referred to the “importance of universal values such as freedom, democracy, basic human rights and rule of law”. It also defined the partnership as strategic. The joint statement thus attempted to integrate Thailand into the Arch of Freedom and Prosperity based on these common values and interests, and Japanese-Thai relations into Japan’s grand strategy – regardless of the recent coup.

Five years later, elected Prime Minster Yingluck Shinawatra and Prime Minister Yoshihiko Noda of the Democratic Party of Japan reiterated this commitment to the shared values in their March 2012 Joint Statement on the Strategic Partnership.

General Prayuth’s coup of May 2014 posed a major challenge to Shinzo Abe, who had returned to the premiership in 2012. It undeniably violated the spirit of the Japanese-Thai strategic partnership. At the same time, the alliance with the United States remained the lynchpin of Japan’s security. Undermining the harsh response of the United States and the G7 nations by continuing business as usual was therefore not a conceivable option (Aizawa 2021: 175–177). The initial response was thus harsher worded than in 2006. The current Prime Minister and then Foreign Minister Fumio Kishida (serving 2012–2017), stated that the coup was “deeply regrettable (遺憾)”, rather than “regrettable (残念)”. Japan “strongly urged (強く求める)” the restoration of democracy, while in 2006 this was only “strongly hoped (強く期待する)”.

At the same time, Japanese investment in Thailand had made the kingdom an “indispensable economic partner” for Japan as Kishida stated when visiting Bangkok in May 2016. And the kingdom has one of the highest number of Japanese residents, whose safety had to be ensured.

Understanding this, the junta reached out to the Japanese business community. In the following days and weeks, they served as a crucial go-between the Japanese government and the Thai junta, successfully lobbying for working with the new government (Aizawa 2021: 178–180). But Tokyo was also very much aware that a complete refusal to work with General Prayuth’s government would only lead to a heavier reliance on the People’s Republic of China, which had launched the Belt and Road Initive only in the previous September. Finally, in October 2014, when it had become clear that the junta would remain in power for the time being and the reaction of EU and USA remained very limited, Prime Minister Abe decided to be the first head of a G7 government to hold a bilateral meeting with Prayuth on the sidelines of the Asia-Europe Meeting in Italy. A second meeting followed the very next month during the East Asia Summit in Myanmar. In comparison to the initial response, the wording was gradually toned down. Japan “strongly expected (強く期待)” a “prompt” restoration of democracy in Italy, but merely “expected (期待)” it in Myanmar.

In February 2015 Japan was the first G7 nation to receive General Prayuth. This further normalization of the relationship provided much sought international legitimacy for the junta. But in the official Joint Press Statement confirmed, Prayuth had to confirm “democracy, the rule of law, and human dignity” as “shared values”. He also publicly promised the return to electoral democracy according to the junta’s political roadmap. This wish for a swift return to democracy was reiterated in subsequent meetings, but overall the relationship returned to the status quo ante. The constitutional referendum of 2017 and the elections of 2019 despite their flaws was then accepted as a return to democracy, as did the EU and the USA.

The Meaning of ‘Free’

The Japanese engagement with the junta has been criticized on principle. On the other hand, as the regime critical Matichon Weekly expressed it, the engagement allowed to pressure Prayuth to publicly express his commitment to electoral democracy as well as to promise an election the following year on an international stage (Matichon 2015: 10). The relatively quick normalization of bilateral relations was also be criticized as being inconsistent with a value-based Japanese foreign policy. But the Japanese deemphasizing of civil liberties and human rights and foregrounding of the rule of law as a prerequisite for foreign investments when dealing with the junta was very much in line with overall articulations of Japanese foreign policy by the Abe government (Aizawa 2021: 183). This occurred of course in response to a raising PRC especially in Southeast Asia. Shinzo Abe’s speech, The Bounty of the Open Seas: Five New Principles for Japanese Diplomacy, that was to be held in Jakarta in January 2013 but was ultimately only published, differentiated already between protecting civil and human rights, upholding the international rules-based order, and keeping national economies open and free as separate principles. Implicitly, this allowed for pursuing human freedom and democracy, and economic openness separately. The speech A New Vision from a New Japan given the next January at the World Economic Forum only referred to democracy once, as a necessary foundation for the rule of law, which alone can guarantee “freedom of movement of people and goods” and through it ensure prosperity. This was reiterated during the Address at the Opening Session of the Sixth Tokyo International Conference on African Development given in Nairobi in August 2016, which has been identified as the official launch of A Japanese Free and Open Indo-Pacific Strategy (Green 2022: 131). In Bangkok in 2019, when giving an interview to the Bangkok Post during the 2019 ASEAN Summit, Abe omitted all references to democracy and shared values – in line with the ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific launched that year. The meaning of freedom in the Indo-Pacific as well as in the Japanese expectations of its strategic partner meant first of all economic freedom.

Two Legacies for Japanese-Thai Relations

Bilateral cooperation with Thailand under Prime Minister Fumio Kishida continues on the trajectory shaped under Abe. The focus is on areas where intergovernmental cooperation is mutually wished for, in particular in regard to Japanese investment in Thailand. Questions of shared values and democracy are meanwhile avoided in the public statements. In 2022, Kishida has visited Thailand twice. Neither the statement of the Japan-Thailand Summit Meeting in May nor the statement about the Elevation of the Relations to a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership from November mentioned the contentious terms. The Five-Year Joint Action Plan agreed upon in November merely mentions a joint upholding of the rule-based international order and principles.

One of the most impactful legacies of the Abe’s premiership is the reform of Japanese defense policy, which aimed at making Japan a “normal” country in this regard and to ultimately amend article 9 of Japan’s postwar peace constitution. Restrictions on exporting military equipment were lifted in 2014. This aimed at allowing for bilateral cooperation in development and production of arms to support modernizing the Japanese Self-Defense Forces, but also to develop and strengthen bilateral defense ties. Attempts under Abe to sell equipment to Thailand, such as an air defense radar system, or sign an agreement about future cooperation as it was done with the Philippines or Indonesia failed. Policy and possibly also personal continuities allowed for the signing of an agreement on the Transfer of Defense Equipment and Technology during Kishida’s inaugural overseas trip to Southeast Asia in May 2022. Kishida had briefly been minister of defense in 2017.

Looking Forward

Under Shinzo Abe Japan was the first G7 nation to engage with the post-coup government of General Prayuth Chan-o-cha on a bilateral basis. This contradicted joint Japanese-Thai statements about shared values signed in 2007 and 2012 but were in line with the general trajectory to emphasize the openness of the Indo-Pacific for business over the freedom enjoyed in the region. The continuity of the engagement with the military government will also have contributed to the deepening of defense ties finally achieved by Prime Minister Kishida in May 2022, who served as foreign and defense minister under Abe. All of this explains General Prayuth’s exuberant assessment of the longest-serving Japanese prime minister on Facebook. At the same time, this engagement could easily have resulted in deteriorating the relationship with Thailand’s largest party, Phuea Thai, tied to the Shinawatra family. The likewise rhapsodic description of Abe in the posts by Thaksin and Yingluck Shinawatra demonstrate that this did not happen. This can be explained by Shinzo Abe balancing the official relations with General Prayuth’s governments with a personal and informal exchanges with exiled prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra as Thaksin revealed in his condolence message on Facebook. From a realist perspective, Shinzo Abe’s legacy for the future of Japanese-Thai relations appears positive. But Thailand is changing and with it Japanese-Thai relations. First, as the 2019 elections and the 2020/21 student protests have demonstrated, younger Thais have embraced democracy and human rights as Thai values. Second, the present partnership is very much an economic one. But Thailand has become less attractive for Japanese FDI, while Chinese investment is increasing. This erodes the basis of the relationship. Going forward, reemphasizing democracy and human rights as shared values, as in 2007 and 2012, might therefore serve Japan well to balance Japanese relative loss of economic hard power in Thailand.

David M. Malitz

Senior Research Fellow, DIJ, Japan

Banner Image: Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe (R) writes his name in a condolence book for the late Thai King Bhumibol Adulyadej at the Thai Embassy in Tokyo on October 14, 2016. Salma Bashir Motiwala, Shutterstock

Reference

Aizawa, N. (2021). The Japanese Business Community as a Diplomatic Asset and the 2014 Thai Coup d’État. In J. D. Ciorciari, & K. Tsutsui (Eds.), The Courteous Power: Japan and Southeast Asia in the Indo-Pacific Era (pp. 172-196). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Green, M. J. (2022). Line of Advantage: Japan’s Grand Strategy in the Era of Abe Shinzō. New York: University of Colombia Press.

Kobayashi Hideaki 小林秀明. (2010). Kūdetā to Thai seiji: Nihon taishi no 1035hi クーデターとタイ政治―日本大使の1035日. Tokyo: Yumani shobō.

Matichon Weekly มติชนสุดสัปดาห์. (13–19 February 2015). Patinya ‘Japan’: Lueaktang ton pi 2559 ปฏิญญาเจแปน: เลือกตั้งต้นปี 2559 Matichon Weekly มติชนสุดสัปดาห์, 1800: 10

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan 外務省. (2022, May 25). Kaigai ni okeru tai-Nichi seron chōsa Reiwa 3-nen do ASEAN kekka shōsai shitsumon bun/sentaku shi 海外における対日世論調査 令和3年度 ASEAN 結果詳細 質問文/選択肢. Retrieved November 16, 2022, from https://www.mofa.go.jp/mofaj/files/100348514.pdf