Reviewing Indonesia’s presence at the international stage should be based on their concrete foreign policy decisions. Among several foreign policy sectors, economic interest is placed at the centre of gravity. Jokowi’s main priority to fulfil economic interests also manifested in Indonesia’s foreign policy priorities by promoting “economic diplomacy” at the forefront of its current international engagement. Indonesia’s economic diplomacy agenda is aligned with the domestic goals and vision, mainly to pursue national aim of higher economic growth and infrastructure development. One of the most notable Jokowi’s economic diplomacy decisions is Indonesia-China Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) cooperation. This article will analyse Indonesia’s BRI cooperation and some political-economic dynamics around them.

Indonesia’s Position and Perception Towards the BRI

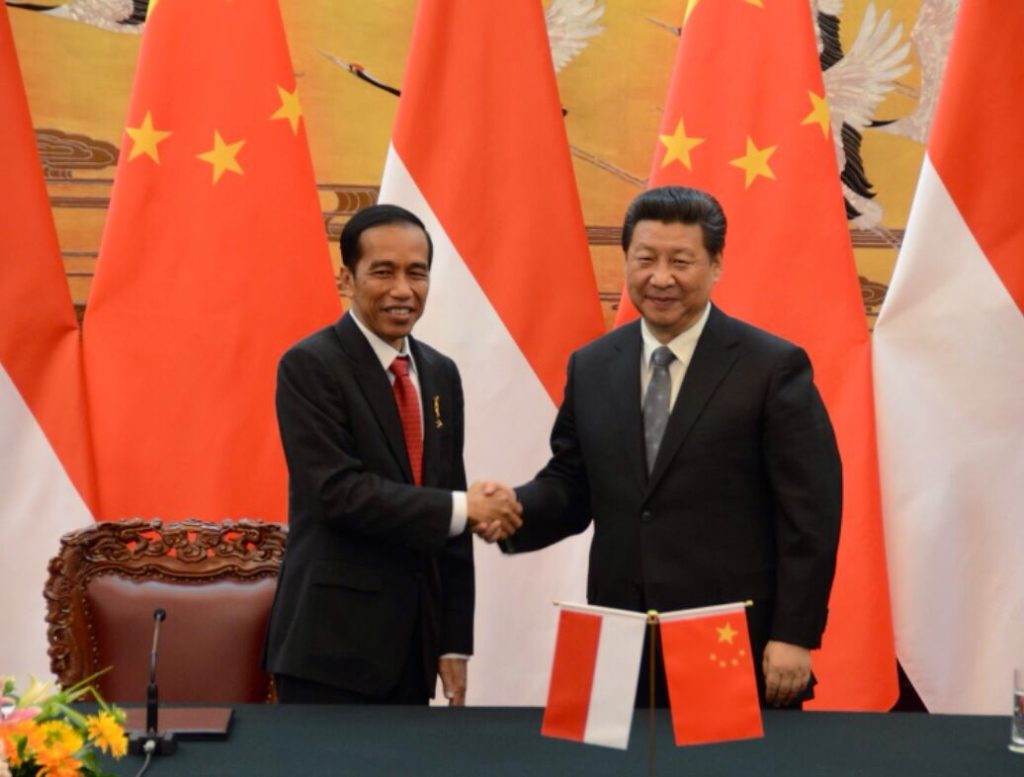

During the visit of China’s President Xi Jinping to Indonesia in 2013, he announced the interest of Chinese government to develop maritime partnership through the 21st Maritime Silk Road mechanism. At that time, Indonesia is under the leadership of President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, so the maritime development was just paid scant attention on his foreign policy priorities. However, both governments were committed to elevate the engagement into a “Comprehensive Strategic Partnership” level.

As the 2014 presidential election results made President Jokowi to take over the next leadership, Indonesia’s foreign policy priority follows the successor’s visions. Jokowi’s first term foreign policy was much weighted on the vision to expand its maritime presence and power, aligned with his election manifesto, Jokowi introduces the concept of “Global Maritime Axis” or “poros maritim dunia” to transform Indonesia as a maritime nation. China grasped Jokowi’s vision as the potential door to open in elevating stronger bilateral partnership.

China is reportedly the first country visited by Jokowi after inaugurated to attend the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Summit in 2014 and met his counterparts. Apart from showcasing his maritime-axis vision to the world, Jokowi announced its commitment to join the China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and to incorporate Indonesia’s global maritime vision with China 21st Maritime Silk Road (MSR). The visit opened the door of Indonesia-China cooperation under the framework of BRI. The second meeting happened in March 2015 at the Boao Forum whereby Jokowi and Xi released a joint statement and underlining the pledge to develop a stronger maritime partnership.

In the 9th East Asia Summit (EAS) 2014 held in Nay Pyi Daw, Myanmar, President Jokowi reemphasised his vision for “global maritime nexus,” in which the China’s MSR is definitely complementing Jokowi’s ambitious maritime agenda. As Jusuf Wanandi argues, the BRI initiative is clearly benefiting Indonesia, but the scale depends on Jokowi’s ability to develop the synergy between the BRI and domestic connectivity agenda. The most potential cooperation was relied on the Action Plan of Indonesia Ocean Policy 2016-2019 that correspond with China’s BRI cooperation priorities.

The effective way to understand Indonesia’s position towards the BRI is by reviewing Jokowi and his administration’s public statements. At the 1st BRI Forum in 2017, Jokowi was expressing his optimism and support that the BRI will result the greater industrialisation and infrastructure development in the region and even appreciate the initiative of being realistic and concrete. In an interview with the South China Morning Post (SCMP), Jokowi reiterated Indonesia’s relationship with China will focus on infrastructure and manufacturing developments as featured in the BRI.

Since then, Indonesia keeps consistent to upgrade the cooperation under the framework of BRI. However, at least until 2018, there is as yet no concrete infrastructure projects agreed between Indonesia and China due to differences in perceptions on what BRI projects are. China considers all infrastructure projects and economic interactions as BRI cooperation, meanwhile Indonesia only count the projects that have committed since Xi and Jokowi’s leadership period. 1 Hence, the political commitments between two countries over BRI cooperation are moving forward.

In 2018, Indonesia’s President Special Envoy and Coordinating Minister for Maritime Affairs, Luhut Pandjaitan visited China and pointed out that both countries are natural partners in the BRI. Along with his counterpart, China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi, the two states committed to fully implement the BRI cooperation consensus and advance the development of Indonesia’s Regional Comprehensive Economic Corridors which are also tapped by the BRI initiative. Luhut was even noted that Indonesia’s relations with China has always been the privileged direction of Jakarta’s foreign relations, signalling Jokowi’s high pleasure with Beijing.

A year later, Indonesia proposed 28 projects worth US$ 91.1 billion to be considered by China’s investors as part of the BRI cooperation. At the side-line meeting between Indonesia-China during the G20 Japan Summit in 2019, President Jokowi made a special funding request to President Xi, noting that Indonesia has not been among the biggest beneficiaries of BRI. Foreign Minister Marsudi stated in 2019 that Indonesia attaches great importance to the BRI initiative and looks forward to promote stronger partnership through this platform. Seeing these statements coming from Indonesia’s high-level officials, Indonesia is highly valuing the BRI partnership and there is no ambiguity for Jakarta’s position on it.

Domestic Criticisms and Oppositions towards China’s BRI

However, numerous negative sentiments and issues are challenging Indonesia’s stance and perception towards the BRI. The initiative was arguably facing several negative sentiments domestically surrounding the issue of debt-trap, loss of sovereignty, and the entry of Chinese workers to Indonesia. 2 The CSIS study suggests how the lack of awareness and information about the BRI results the growing concerns about Indonesia’s dependence on China. 3

Indonesia has been more cautious in its approach to the initiative, as the major obstacle to the BRI development is public opinion. As Indonesia’s foreign engagement can be assessed democratically by the public, the concerns of Indonesians in general is crucial. In fact, Jokowi’s challenges on the BRI is straightforwardly coming from the domestic constituents. In three consecutive years, Jokowi faces huge protests demanding to close the gate for Chinese workers in the BRI projects. Indonesian prominent economists like Faisal Basri and Emil Salim in many occasions also criticise some aspects of the BRI such as on its investment quality and the entry of Chinese workers.

The Vice Chairman of Indonesian House Representatives (DPR), Fadli Zon even warned Jokowi for the BRI’s threat to national politics and economic sovereignty. Former Jokowi’s Coordinating Minister for Economy, Rizal Ramli, Luhut’s predecessor wrote that BRI is a double-edged sword because of its “lend-to-own” scheme that will allow Beijing to wrestle control of Indonesia’s strategic assets.

Apart from debt-trap risks, Indonesia’s government has been criticised over the consequences of BRI projects to the environment. In 2019, 240 civil society organisations opposed the BRI’s hydropower dam project in North Sumatra as it would danger the endemic species of orang-utan. Another BRI project, the Jakarta-Bandung high-speed rail also criticised for a lack of proper environmental impact studies. Indonesia’s prominent environmental-based institution, The Indonesian Forum for Environment or WALHI was also concerning about the BRI investments on dirty energy electricity projects and coal mining financing. With these series of criticisms, the BRI domestically in Indonesia is under critical challenge.

Chinese President Xi acknowledges the critics towards the environmental aspect of BRI projects and introduces some feedback solutions. In the 1st BRI Forum, Xi proposed an establishment of the International Coalition for Green Development, to integrate the green development agenda with the BRI projects worldwide along with the United Nations Environment and Ministry of Ecology. Xi also called for the initiative to be “open, green and clean” during his speech at the 2nd Belt and Road Forum in 2019.

Beijing’s government strategically promotes a pro-environment and contra-climate change narrative via its guidance on promoting the Green Belt and Road and the Belt and Road Ecological and Environmental Cooperation Plan. 4 At the latest Boao Forum for Asia (BFA) Annual Conference 2021, Xi reemphasised China’s commitment to green development, infrastructure, energy and finance under the BRI umbrella.

Indonesia has also anticipated such environmental-based criticisms with several commitments. Minister Luhut claims that Indonesia is demanding for the use of environmental-friendly technologies and reject the second-class technology that will bring negative impacts to the ecosystem in the BRI projects. His Deputy, Ridwan Djamaluddin also stated that even the government offers the power plant investments to China, Indonesia will keep balance the economic benefits with the environmental preservation in dealing with Beijing and suggests that Jakarta is on the right track. Meanwhile, on the issue of BRI trap, Indonesia’s Foreign Ministry spokesperson Arrmanatha Nasir responds by stating that Jokowi puts emphasis on ownership and national driven approach in dealing with China—that BRI will follow national development strategy, not global or long-provider driven.

Hence, the issues around the BRI cooperation have influenced Indonesians’ perceptions to China. According to a poll by the Pew Research Center, Indonesians who have favorable views of China has declined over time due to a rising concerns about Jakarta’s dependence to Beijing. The data shows 53 per cent of respondents in 2018 had a confidence to China’s stronger partnership with Indonesia, down from 66 per cent in 2014. Another survey from Lingkaran Survei Indonesia (LSI) found that 36 per cent Indonesians see China bring a bad influence to Indonesia. These facts show how Beijing-Jakarta relationship is facing domestic challenges and may become the significant hurdle for a closer BRI cooperation.

With this high political content and risk, Indonesia’s economic diplomacy is primarily managed by the foreign ministry. Although specifically on the BRI, Indonesia has anticipated the risk of debt-trap by emphasising business-to-business (B2B) mechanism over the BRI partnership. Minister Luhut as the vocal point of Indonesia-China relations claimed many times that Indonesia would not be trapped with the negative consequences of BRI with this B2B arrangement. However, considering that BRI remains under the Chinese government control, is it difficult to separate the political motives behind it or what Stromseth claims as Beijing’s “economic statecraft” 5 and Dunst suggests as a gateway for China’s global expansion and anti-U.S. political units. 6

Considering the involvement of business or state-owned enterprises within the BRI partnership, Indonesia’s economic diplomacy towards the BRI is not fully organised by the foreign ministry, but also involving other relevant offices. Luhut Pandjaitan for instance is the most active minister regarding the BRI partnership, backed with his position as Indonesia’s Coordinator for Cooperation with China and Coordinating Minister for Economic Affairs.

Aware of the issue is easily being politised, Jokowi’s administration responds that BRI is undergone with a win-win engagement. The government is trying to pull the BRI under the eyes of commercial views, not political ones. The B2B arrangement of BRI implementation is a way to support this narrative, Jokowi put emphasis on non-government funding scheme. Chief of the Indonesian Chamber of Commerce or KADIN, Rosan Roeslani supports the government position on BRI by suggesting that Indonesia will get huge benefits from infrastructure development into other commercial benefits. Jokowi’s approaches by not integrating politics to the BRI has made the domestic grievances remains under-controlled- despite the pandemic, Jokowi and Xi even continue to pursue a greater BRI partnership.

The BRI cooperation of Indonesia-China faces a variety of political dynamic domestically. However, Jokowi’s government attempts to manage it under win-win cooperation with a strong involvement of business sectors. Indonesia’s government tries to separate the political dimensions from China’s BRI partnership given to its high disruption. The BRI in Indonesia would not be far from criticisms and political opposition from different groups. As long as both governments do not carry the cooperation under what called “economic statecraft,” it will be sustainable.

Noto Suoneto

Noto Suoneto is a foreign policy analyst and host of Foreign Policy Talks Podcast. He is also part of Y20 (G20 Engagement Group) Indonesian Presidency 2022.

Notes:

- Siwage Dharma Negara and Suryadinata, Indonesia and China’s Belt and Road Initiatives: Perspectives, Issues and Prospects, (Singapore: ISEAS Yusof Ishak Institute, 2018). ↩

- Nur Rachmat Yuliantoro, “The Belt and Road Initiative and ASEAN-China Relations: An Indonesian Perspective,” The Belt and Road Initiative: ASEAN Countries’ Perspectives, edited by Yang Yue and Li Fuijian, (Beijing: Institute of Asian Studies and World Scientific Publishing Ltd., 2019), pp.81-102. ↩

- Yose Rizal Damuri, Vidhyandika Perkasa, Raymond Atje, and Fajar Himawan. Perceptions and Readiness of Indonesia Towards the Belt and Road Initiative, (Jakarta: Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) Indonesia, 2019) ↩

- Johanna Coenen, Simon Bager, Patrick Meyfroidt, Jens Newig, and Edward Challies, “Environmental Governance of China’s Belt and Road Initiative,” Environmental Policy and Governance, Vol.31, Issue 1 (2021), pp.3 -17. ↩

- Jonathan R. Stromseth, “Navigating Great Power Competition in Southeast Asia,” Rivalry and Response- Assessing Great Power Dynamics in Southeast Asia, edited by Jonathan R. Stromseth, (New York: Brookings Institution Press, 2021), pp.1-31. ↩

- Charles Dunst, Battleground Southeast Asia: China’s Rise and America’s Options, (London: London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) Ideas, 2020). ↩