In early 2017, I started to work in visual ethnography for my new border study in Pattani, on a project about being ‘queer Muslim’. Since I wrote a reflexive article “Pondan under the Pondok” (Samak 2017a) about my childhood memories of homosexual practice in the Islamic school where I did religious studies for six years, those experiences still keep me questioning, how did this happen at a place that seems to be so strongly anti-homosexuality?

In that same year, there was a big argument among scholars and activists both inside and outside of Thailand’s three “Deep South” provinces debating on how to open up homosexuality to public discussion, and how to make queer people and identity visible in the community (see Anticha 2017). At that time talking about being queer in Islam became a very sensitive topic. Then, one day my former student from Islamic college asked if I ever saw stray sheep in Pattani? I wondered why I never noticed these sheep that lived among us. Suddenly that question came to me again; why there were so many sheep here, and how did they look so dirty, wandering around like stray dogs.

Nonhuman subjects

Reading Haraway (1991), gives us the idea of non-human actors that challenge our assumptions about social actors and the hybridity of human and nonhuman in everyday life. There is a way to understand the social and cultural contexts of Muslim society in Thailand’s Deep South using the framework of object-oriented ontology in posthumanism (Ming 2019). I reworked my project researching queerness in Muslim society to also look at nonhuman actors as one of the social actors that narrates social and cultural life, as they are living in the same environment as us humans.

After following sheep for three months, I realized that they’re not strays, but were living in shared pens next to the mosque, together with other sheep and animals that belonged to people in the community. I used GPS to mark the spots where the sheep went around the neighborhood, similar to the way anthropologists follow a head villager to learn about a village’s setting. In my case, the sheep took me to all the places where they usually go, including the graveyard, the Islamic school, the mosque, the market, shops and the military checkpoints. The owners told me that the sheep know where they can go and where they cannot cross, so animals have their perception of place and sometimes they can realize boundaries between Thai Buddhists and Melayu Muslims by looking at their spots beside the road.

Sheep are nonhuman – that is, animals – but later I realized there are other nonhuman subjects to be considered. I noticed through spending nights in tea shops that people kept telling stories of djinn (originally an Arabic term; a supernatural being created by God that lives in a world parallel to humans, but invisible. Sometimes the locals call them pi – Thai for ghost). Reading Fuhrmann’s Ghostly Desire (2016) provided me the possibility to think about queer personhood, which I compared to the djinn in Islamic belief, to compare the invisibility of queer people and Jinn. In stark contrast, there are some subjects that locals like to talk about, but other subjects that they don’t discuss at all.

The third nonhuman subject I focused on was “waves”. I found that the beaches of the South are a kind of “comfort zone” for locals and the many Muslim women who sell food there for a living. I collected plastic waste from the beach to create the “waves” in my art; those objects also served as my narrator, telling me the traces of life lived there, and the waves became to symbolize, for me, gender and livelihood. I followed some art students to Thepha village in neighboring Songkhla province, and we learned about the different words – both Thai and Malay – that locals used to describe different kinds of waves, and how it showed how they relate to their environment as part of their livelihood and their everyday life relation with nature. But these villages were under order of the government to relocate in order to build a new power plant, so many of them went to protest in Bangkok. I made a documentary film to both record the situation and tell the sense of the waves of the south, in art form.

Art and anthropology in practice

Art is not only a subject for anthropologists to focus on material culture, but also an active platform for for change – in the conception of art and in debate over the definition of socially-engaged art that is associated with a sense of culture (Morphy and Perkins 2006). My video work “Sheep” (2017-2018) implies hierarchy and religious violence and represents another face of Muslim society in the culture of the Deep South, showing how humans interact with the nonhuman from our human perspective, as well as serving as metaphor for the people of the Deep South within the Thai state and violence (Thanavi 2018). Creating myths about ‘stigmatized sheep’ is no different from how the state attempts to define people in the Deep South (Samak 2017b).

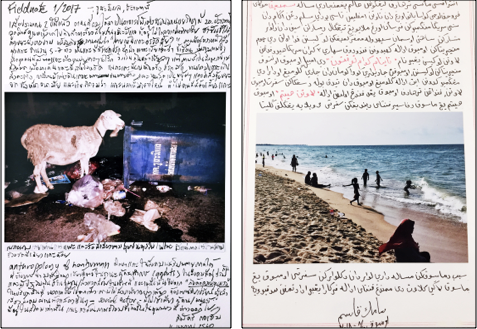

In this “nonhuman ethnography” project (2017-2020), I have created work across the anthropological and art practice of photography by making “field-notes,” combining the knowledge and methodology of academic research with contemporary art. The field-notes were exhibited at the first Bangkok Art Biennale (BAB) in 2018, after I discussed “untranslatability” with the curator Patrick D. Flores. I decided to translate my notes originally written in Thai into Melayu, using Jawi script. This is my way of opening discussion with the audience, to show how narratives and knowledge – become burden and boundary on our understanding. Also I wanted to give a feeling of the complexity of ignorance and our cultural differences; even as citizens of the same country, the gap between the local Melayu language and Jawi script remains unsurmountable for “normal” Thais from outside the region. The only way to understand is through photos or visuals. Somehow the work tries to communicate the distance of this relation, to show Thai audiences how these lives have been ignored.

For example, in the “waves” project I discussed the meaning of waves. A wave is usually a voice, but it can be a noise that no one wants to hear, as well as the voice of the Melayu Muslim local people. ‘A Thin Veil’ (2018), is a silent video work, with nonhumans telling the story of how “waves” relate to the environment, society, culture, and people. The silence of the waves in this documentary is a metaphor for the waves of social life in Melayu culture that are often ignored. The villagers of Thepha have been fighting with the state, to stop a coal-fired power plant from destroying the waves just offshore. Waves can also refer to the situation with fundamentalists; in the south they talk about the “new wave” to refer to Islamic fundamentalists (Willis 2019).

The second video on waves, “By The Shore of The Sea” (2019) is the narrative of a woman and her experiences with waves in her hometown, include her own story reflecting on her own identity and self, as a Muslim woman. In the video she voices her own narrative and that of another woman; she also voices the waves within her mind that can never be claimed. This short video explores all sounds as being waveforms; it is the crashing of the sounds of strong winds, sea waves, and women’s voices. To find what we want to hear – or bear to hear it – these waves are always rolling within our minds from one shore to another.

Considering nonhumans as construction/object, checkpoints are both a symbol of state control and a subject that contextualizes socio-cultural politics in everyday life. This work, “Forever Checkpoint” (2019), was produced in the form of a romantic music video to make a stark contrast with the symbolic violence that the checkpoint represents. Physical and violent assaults continually occur in the three southernmost provinces, which has constructed an image of the border provinces as “culprits.” The militarized border – with more than 2,000 checkpoints – is self-explanatory of how fear and anxiety are constructed by the military regime in Thailand. Also by showing how people under suspicion are seen in everyday life at the military checkpoints – how people are assumed to be unidentified, mysterious and invisible – is my attempt to represent interpretation (Myers 2006) of violence by the Thai state.

Visual ethnography of invisible queer

In late 2017, while waiting at a barber shop on a street near the university in Pattani, I saw two Muslim girls wearing white veils (hijab) stop their motorbike in front of the shop. They waited for a while, and the barber came out and spoke to them. A bit later, while cutting my hair, the barber told me that the two sisters asked him to cut their hair like a man’s. The barber felt uncomfortable because he rarely cuts women’s hair, but he understood that these two girls would have no choice – where could they go without being judged, two women who want the hairstyle of a man?

This observation – a sort of field research – inspired me to make video art on queer Muslims. “The Day I Became…” (2019) is the story of a tomboy 1 Muslim who left their hometown in Yala to work in Bangkok. Moving out of their home was not just moving away, but also feeling that their sexual (dis)orientation was always judged as sinful. Fleeing home did not immediately provide a comfort zone of individual space – now s/he still struggles with his/her family about religion, social stigma, and family shame. Moving out is not merely a matter of space, but it is also moving away from their former religion. A haircut is not only a gender decision, but also a passage in life to being an “ex-Muslim.”

To know nonhuman lives is to see a secondary reflection that helps us to understand how queerness is impacted by normality and non-acceptance in religious discourse and social regulations. Local Muslims have said “no homosexuality in Islam, no gays in our community.” This shows how queer people have to live or feel in Muslim society – hidden under the carpet. At the southern border, people are dehumanized not always by acts of the state on locals, but also in the ways locals disrespect queer people. Lastly, in talking about nonhuman/queer narratives, we can consider how djinn and queer are both invisible. But in reality, stories of the djinn still have space for telling, but queerness never enters the narrative or conversation.

Samak Kosem

Research Fellow, Center of Excellence in Women and Social Security, Walailak University

PhD. Student, Faculty of Social Sciences, Chiang Mai University

References:

Anticha Sangchai. 2017. “กรณีห้องเรียนเพศวิถี: สิทธิความหลากหลายทางเพศกับชายแดนใต้/ปาตานี” [SOGIE Rights and Thailand’s Southern Border Provinces/PATANI: The Case of Buku’s Gender and Sexuality Classroom], Thammasat Journal of History. Vol.4, No.1 (January-June), pp 209-268.

Fuhrmann, Arnika. 2016. Ghostly Desires: Queer Sexuality and Vernacular Buddhism in Contemporary Thai Cinema. (Durham: Duke University Press).

Haraway, Donna. 1991. Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. (New York: Routledge)

Ming Panha. 2019. “หลังมนุษยนิยมกับวรรณคดีวืจารณ์: กรณีศึกษาด้านภววิทยาเชิงวัตถุของแกรห์ม ฮาร์แมน” [Posthumanism and Literary Criticism: A Case Study of Object-Oriented Ontology by Graham Harman]. In Suradech Chotiudompant (ed.), นววิถี: วิธีวิทยาร่วมสมัยในการศึกษาวรรณกรรม [New Turns in The Humanities: Contemporary Methodology in Literature Studies]. (Bangkok: Siam Panya Publishing).

Morphy, Howard and Perkins, Morgan (eds.). 2006. The Anthropology of Art: A Reader. (New Jersey: Blackwell Publishing).

Myers, Fred. 2006. “Representing Culture: The Production of Discourse(s) for Aboriginal Acrylic Paintings”. In Howard Morphy and Morgan Perkins (eds.), The Anthropology of Art: A Reader. (New Jersey: Blackwell Publishing).

Samak Kosem. 2017a. “ปอแนใต้ปอเนาะ: ชาติพันธุ์วรรณาย้อนมองดูตัวเองของ“เควียร์มุสลิม”และความทรงจำวัยเด็กในโรงเรียนสอนศาสนา” บPondan under the Pondok: Reflexive: Ethnography of “Queer Muslim” and Childhood Memories in the Religious School, Thammasat Journal of History. Vol.4, No.1 (January-June), pp.161-206.

Samak Kosem. 2017b. “สหสายพันธุ์นิพนธ์ของแกะเร่ร่อนในรูสะมีแล” [Multi-species of the Stray Sheep in Ru-Sa-Mi-Lae], in Thanom Chapakdee et al (eds), เปิดโลกสุนทรีย์ในวิถีมนุษยศาสตร์ (Exploring Aesthetic Dimensions in the Humanities). Conference proceeding on 11st Thai Humanities Forum, 8-9 September 2017, Srinakharinwirot University. Pp.709-719.

Thanavi Chotpradit. 2018. “Sheep (بيريڠ): Documentary of the Nonhuman”. Chiang Mai Art Conversation. <http://www.cac-art.info/users/thanavichotpradit/journal/60/> (accessed 25 April 2020).

Willis, David. 2019. “David Willis in Conversation with Samak Kosem”. Degree Critical. <https://degreecritical.com/2019/03/22/david-willis-in-conversation-with-samak-kosem/> (accessed 25 April 2020)

Notes:

- “Tomboys” or “toms” in the Thai context are lesbians who have a clear “masculine” style of dress and/or speech ↩