Twenty years after the fall of Suharto how has the country dealt with the legacy of the authoritarian New Order’s repressive policies and actions? The story of transitional justice, or reckoning of the past, is one of abject failure with no significant convictions or substantive accountability for past human rights abuses. At the same time, it is also a story of stubborn persistence where the failure of official pathways to justice has led activist and civil society groups to pave new paths that rely less on the state and more on society. Said differently, the politics of Indonesia’s past hasn’t gone away; its arc has shifted from top-down to bottom-up, from official to informal, and from redress to recognition.

The lack of official progress belies the impressive number and variety of proposed initiatives to address the past that have been put forth and debated over the past two decades: criminal prosecution, fact-finding, truth commissions, legal reform, reparations, documentation and memorialization (ICTJ-Kontras 2011). This diversity partly reflects the number and variety of human rights violations that occurred during Indonesia’s authoritarian era including mass killings, counter-insurgency, mass incarceration, forced labor, forced detention, kidnappings, street violence, torture and executions.

At the same time, this diversity also has a pattern and a trajectory along three broad areas of transitional justice; the retributive path, the restorative path, and the reparative path. Each of these in turn include official institutional initiatives that failed and informal non-official paths that followed, producing a recursive relationship between official and societal measures for transitional justice.

Trajectory 1: The Judicial Path

For activists and advocates of transitional justice, the prosecution of perpetrators in a court of law is generally considered the holy grail of addressing past human rights abuses.

Official measures of retributive justice in the post-Suharto era began with constitutional and legal reform. In particular, new laws stipulated that “all gross human rights violations will be tried in a Human Rights Court” (Law 39, 1999). However, the same law also affirmed that “the right not to be prosecuted under retroactive law” is a “basic human right that may not be diminished under any circumstances whatsoever” (Law 39, 1999) This clause, known as the retroactive principle, straightjacketed transitional justice coming out of the gate and has been used to argue against trying perpetrators for past human rights abuses.

Subsequent laws did allow ad hoc human rights courts to try retroactive cases but because of their restrictive formulation, few cases have actually gone to trial and those that have, have achieved no significant justice. The Ad Hoc Human Rights Court in Jakarta on the violence in East Timor, for example, found only six of eighteen defendants guilty despite overwhelming evidence and all six convictions were later overturned on appeal (Cohen 2003). In the case of the ad hoc trials on Tanjung Priok, where prosecutors tried military and security forces for firing upon demonstrators in northern Jakarta in 1984, the courts convicted twelve out of fourteen defendants but a subsequent appeals court vacated all of the convictions (New York Times 2005).

Frustrated with the courts and tribunals within Indonesia, activists and advocates have also looked abroad to international courts and in some cases foreign courts to try alleged perpetrators. The UN Special Panels in East Timor are one prominent example but activists have also gone elsewhere such as to US and Australian courts (Center 1992; ABC News 2007). These trials have led to convictions in some cases but all lack jurisdiction and enforcement mechanisms to prosecute high-level perpetrators in Indonesia proper.

Given these constraints, activists more recently have explored a third path that embraced a legalistic model though only in symbolic terms. In 2015, the fiftieth anniversary of the 1965 massacres, Indonesian activists organized the International People’s Tribunal, or the IPT, as a way to highlight the lived experiences of the survivors of 1965 to the international community (Palatino 2015). The IPT organized survivors, witnesses, experts and historians to testify on the events of 1965 while international figures within the human rights community including justices and lawyers served as judges. After several days of testimony the court issued rulings in favor of the plaintiffs on nine counts including on mass killings, enslavement, torture, enforced disappearance, sexual violence, exile and propaganda (IPT 1965).

Trajectory 2: Reconciliation

A second model within Indonesia’s transitional justice framework emphasizing reconciliation. Loosely, reconciliation is the idea of bringing together different sides of a conflict to acknowledge and resolve past differences.

In Indonesia, the closest the government came to instituting official reconciliation measures was in 2012, when then-President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono’s administration signaled the President’s intention to issue a broad national apology for the country’s most glaring human rights violations that had taken place during the New Order (Jakarta Post 2012). But as soon as news emerged, opposition also began to mobilize making public pronouncements and threats against an apology, effectively dooming the initiative. President Jokowi also flirted with the idea of an official apology before abandoning it due to opposition.

Again, frustrated with the failure of official mechanisms, groups also sought reconciliation in their own ways. One example is an organization of Indonesian ex-PKI members, the families of army generals killed in 1965 and victims of other conflicts who have formed an organization called the Children of the Nation Gathering Forum (FSAB, Forum Silaturahmi Anak Bangsa). Meeting periodically, the group seeks to facilitate dialogue and reconciliation among different factions of the events of 1965 (Lowry 2014).

Another set of initiatives have involved the organization Syarikat, where progressive young members of the Islamic organization NU sought to promote reconciliation around 1965 by engaging in dialogue meetings and joint projects between former members of the PKI and members of the NU community, creating support groups and associations for women victims, joint lobbying to the legislature to end discrimination of former political prisoners and their families and promoting measures to restore their rights (McGregor 2009). Other examples include the use of “islah,” an Islamic form of peacemaking used between the military and victims and families of victims of the Tanjung Priok Massacres, and in Aceh, the use of diyat, an Islamic practice of making payments to the next of kin of those killed or disappeared in conflict (Kimura 2015). These cultural and societal approaches offered openings for reconciliation but also proved problematic and dissatisfying to many of the victims.

The Politics of the Truth

If legal retributive models and reconciliatory initiatives have achieved little by way of transitional justice, what about the practices of truth-seeking and truth-telling?

An early form of truth seeking involved fact-finding initiatives, especially around the events of 1998 and also on the violence in Aceh. These early missions and their subsequent reports were embraced by the human rights and international community for offering a comprehensive and substantive account of events, naming Indonesia’s security apparatus among the culprits of the violence. But the pattern did not continue. Later fact-finding suffered from a lack of credibility, a tendency towards ad hockery, and ultimately a lack of action.

Truth and Reconciliation

Another official mechanism to pursue truth lay in the model of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) that the government decreed in 2000 and established in 2004. NGO and civil society organizations pushed strongly for the law and were encouraged initially that it had the power to investigate gross violations of human rights, but they soon became disenchanted to find that the law also endowed the TRC the power to give amnesty to perpetrators, bar cases addressed in the TRC from going to court, and allow victims to receive compensation only in exchange for amnesty. Seeking to remedy the weaknesses in the law, activists brought a suit to the Constitutional Court which unexpectedly vacated the entire law, leaving the human rights groups legally in the right but without any TRC law at all (Kimura 2015).

A Year of Truth

Given their frustration with the government and the failure of official fact-finding as well as the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, civil society organizations have sought to promote truth in their own way. NGOs and civil society groups like the Coalition for Justice and Truth (KKPK) have highlighted the historical memory and suffering of past human rights violations by pooling resources and coordinating efforts to “amplify the voices of the victims of Suharto’s New Order regime” though public testimonials called “hearing testimonial events” (Ajar 2012).

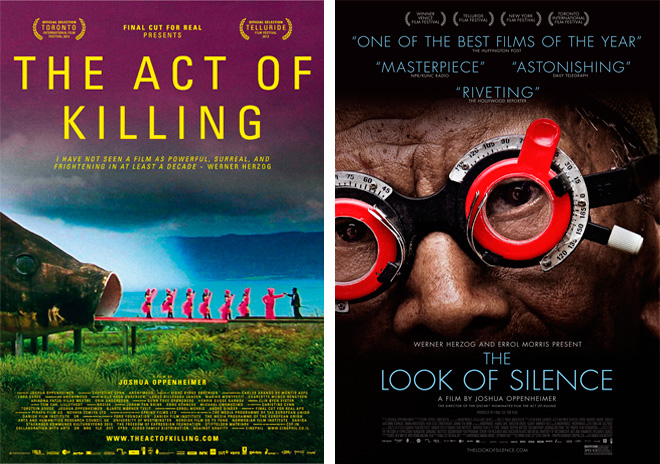

Truth-telling has also emerged through popular culture, most notably in provocative films such as “The Act of Killing” and “The Look of Silence.” More generally, there have been dozens of books published by 1965 survivors, including many women. At the same time, the academic literature around 1965 has also boomed with both Indonesian and international scholars uncovering newfound documents about the role of the military or the role of the international community in the events of 1965.

A National Symposium

The most recent and surprising example in the realm of truth-seeking was the government organized symposium about the different viewpoints of 1965 called the “National Symposium: Dissecting the 1965 Tragedy, A Historical Approach” (Jakarta Post 2016). The meeting was remarkable for being the first of its kind, a government-sanctioned public discussion of 1965. And though there has been limited follow up since the meeting, it was also significant in that an organizing member from the government acknowledged the state role in the killings. The Symposium also produced its own kind of backlash from military-affiliated groups and conservative Islamic organizations, who organized an anti-PKI counter-symposium (Kompas 2016).

Conclusions

The prospects for official transitional justice in Indonesian are dimmer today than at any time since the fall of Suharto. In the context of this highly limited and constrained environment, civil society groups have shifted their focus, largely abandoning big official national approaches and taking matters into their own hands. Relying less on formal institutional activities, advocates have sought to engage their own initiatives that engage in truth-seeking, truth-telling and symbolic forms of justice. The emphasis here is more toward recognition rather than redress and an appeal for more societal support than official actions.

The state has been unable or unwilling to engage in any kind of meaningful process of transitional justice. This refusal is broadly consistent across different kinds of justice including legal/judicial approaches, reconciliatory approaches, and truth-seeking approaches. Nonetheless, the politics of the past refuses to go away in the social and political discourse of Indonesia. There is more discussion and debate than ever about the past and more evidence collected by activists, academics, victims and victims’ families, writers, and documentarians. Of the three modes of transitional justice, the truth-seeking and truth-telling mode has been the most successful if only serving the purpose to “tread water” until further kinds of justice are possible.

Ehito Kimura

Associate Professor

Department of Political Science

University of Hawai’i at Manoa, Hawai’i

Reference

“Balibo 5 Deliberately Killed, Coroner Finds.” ABC News, November 16, 2007. http://www.abc.net.au/news/2007-11-16/balibo-5-deliberately-killed-coroner-finds/727656.

Cohen, David, Seils, Paul, and International Center for Transitional Justice. Intended to Fail: The Trials before the Ad Hoc Human Rights Court in Jakarta. New York, N.Y.: International Center for Transitional Justice, 2003.

“Concerning Human Rights, Pubic Law No. 39 (1999).” The House of Representatives of the Republic of Indonesia. Accessed May 25, 2018.

England, Vaudine. “Indonesian Acquittal Has Shades of the Past.” The New York Times, July 13, 2005, sec. Asia Pacific. https://www.nytimes.com/2005/07/13/world/asia/indonesian-acquittal-has-shades-of-the-past.html.

Findings and documents of the International People’s Tribunal on crimes against humanity in Indonesia, 1965. Jakarta and The Hague: IPT 1965 Foundation, 2017.

Hermansyah, Anton. “1965 Symposium Indonesia’s Way to Face Its Dark Past.” The Jakarta Post, April 19, 2016. http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2016/04/19/1965-symposium-indonesias-way-to-face-its-dark-past.html.

“Helen Todd v. Sintong Panjaitan.” Center for Constitutional Rights. Accessed May 25, 2018. https://ccrjustice.org/node/1638.

ICTJ, and Kontras. Indonesia Derailed : Transitional Justice in Indonesia since the Fall of Soeharto : A Joint Report. Jakarta Indonesia: International Center for Transitional Justice ;Komisi untuk orang Hilang dan Korban Tindak Kekerasan, 2011.

Kimura, Ehito. “The Struggle for Justice and Reconciliation in Post-Suharto Indonesia.” Southeast Asian Studies 4, no. 1 (2015): 73–93.

Lowry, Bob. “Review: Coming to Terms with 1965.” Inside Indonesia. August 2, 2014. Accessed May 24, 2018. http://www.insideindonesia.org/review-coming-to-terms-with-1965.

McGregor, E. Katharine. “Confronting the Past in Contemporary Indonesia: The Anticommunist Killings of 1965–66 and the Role of the Nahdlatul Ulama.” Critical Asian Studies 41, no. 2 (2009): 195–224.

Nur Hakim, Rakhmat. “Ini Sembilan Rekomendasi Dari Simposium Anti PKI – Kompas.Com.” Accessed May 24, 2018. https://nasional.kompas.com/read/2016/06/02/17575451/ini.sembilan.rekomendasi.dari.simposium.anti.pki.

Palatino, Mong. “International Court Revisits Indonesia’s 1965 Mass Killings.” The Diplomat. Accessed May 25, 2018. https://thediplomat.com/2015/11/international-court-revisits-indonesias-1965-mass-killings/.

Pramudatama, Rabby. “SBY to Apologize for Rights Abuses.” The Jakarta Post. Accessed May 24, 2018. http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2012/04/26/sby-apologize-rights-abuses.html.

“The ‘Year of Truth’ Campaign in Indonesia.” AJAR (blog). Accessed May 24, 2018. http://asia-ajar.org/the-year-of-truth-campaign-in-indonesia/.