The biggest change of decentralization in Thailand happened in 1997 together with the passage of the new constitution, widely celebrated as “The People’s Charter.” However, there was a deep concern that this rush might bring severe political conflicts or conflict of interests to the country. Some were afraid that the people were not ready and the mafia would win in the local election. In addition, there were also reports about political assassinations which targeted local politicians and their family members in daily newspapers. These resulted in local politics being seen as ‘bloody’.

There was a good deal of similar political crime reportage and that in turn created a sense of fear in society. This begs the question whether similar political assassinations took place country-wide or only in specific areas. And, What is the exact number of such cases taking place each year? Are these crimes increasing or decreasing after decentralization? And finally, is local Thai politics really as dangerous as people believe (and fear)?

Source: Thairath newspaper, 24 October 2007, front page.

What the National Survey shows

Between 2000 and 2009 there were 481 (100%) assassination attempts on local politicians (both administrative and council officers including candidates and clerk) or 459 cases. 1 In some cases, there were more than one victim attacked in the same incident. From this number, there were 362 (75.3%) deaths. Sadly indeed, this appears a high number. However, in comparison to nationwide murder cases (almost 4,700) and the number of local politicians (around 160,000), the percentage of assassinations it is considerably lower than the earlier number suggests at less than 1%.

Among the 481 victims, 467 (97%) were men and most of these were between 41-59 years old (54.1%). A Gun shot was most common murder method at 93.1%, followed by bombs, 3.1%, then other methods at 3.7%.

When examining murder statistics, it becomes clear that presidents of organizations are in a position of highest assassination risk; records show 139 victims , almost 30%, who are in positions of power. This might be due to the authority a president has in the organization over human resource management and budget allocation. Furthermore, smaller local government organizations see more political violence than larger ones; there were 349 victims, 72.6%, working for Sub-district Administrative Organizations (SAOs).

Table 1. Top 11 provinces with cases of murder attempts on local politicians

Number Province Region Number of cases Percentage

1 Narathiwat South 34 7.1%

2 Pattani South 31 6.4%

3 Phatthalung South 30 6.2%

4 Yala South 24 5.0%

5 Songkhla South 20 4.2%

6 Nakorn-Si-Thamarat South 18 3.7%

7 Nakom Pathom Center 16 3.3%

7 Phetchabun Center 16 3.3%

9 Nakon Ratchasima Northeast 13 2.7%

10 Chiang Mai North 12 2.5%

10 Supan Buri Center 12 2.5%

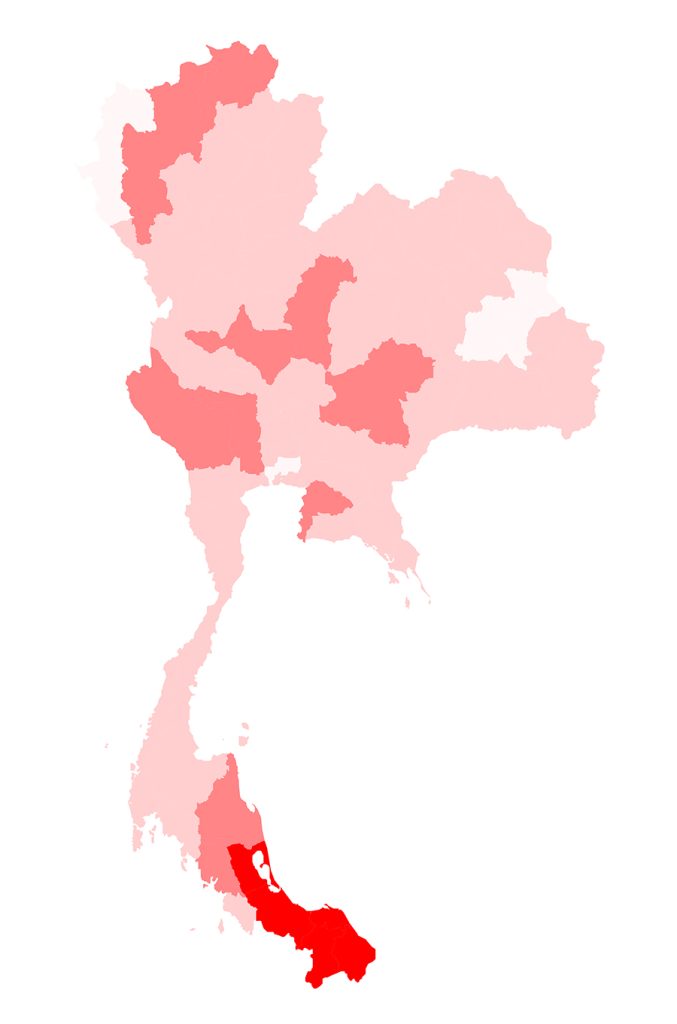

It is interesting to note that although this violence took place widely across the country, there were some crisis areas, especially in Southern Thailand (42.2%), and also the central area (26.4%). Four out of eleven provinces listed above are in the “Deep South”. Narathiwat, Pattani, Yala and Songkhla (in some districts) have experienced difficult situation for a very long time (See the dark red area on Figure 2). In contrast, there are only five provinces that have no recorded murder attempts. Three out of these five provinces are in the north-eastern region (See the white points on Figure 2).

The trend of political assassination that took place from 2000-2009 was unpredictable and unstable. In 2003 and 2005 at 13.3% and 14.1% respectively, the number is high. While in 2008-2009, there was a gradual decrease of incidents in every region of the country.

Looking at these numbers, one should also consider the political situation at the national level. At the beginning of 2003, The Thai government announced the war on drugs campaign. A number of studies have indicated that as a result of this deadly campaign, around 2,500 persons were murdered. 2 In early 2004, after the raid on a Thai army weapon storage facility in Narathiwat, the political situation in the three border provinces in the South grew worse. There was an increasing number of cases of violence —murder, assassinations, bomb planting and so on— and this brought political unrests. The amount of violence in the area rose substantially between 2004 and 2005. 3

The assassination of Charnchai Silapauaychai (นายแพทย์ชาญชัย ศิลปอวยชัย),

In 24 October 2007, Dr. Charnchai Silapauaychai (นายแพทย์ชาญชัย ศิลปอวยชัย) (53 years old), the president of Phrae Provincial Administration Organization, was killed in a shooting. Phrae is one of the Northern provinces that is well-known for its political violence. He is the only PAO president among the eight upper-North provinces of Thailand who has been assassinated.

Prior to the murder, Dr. Charnchai was reportedly at odds with his political opponent, Ms. Siriwan Prassachaksattru. She is an heir of a politically influential well-known family which is one of the old political party leaders in Phrae. Dr. Charnchai failed to appoint Mr. S (Ms. Siriwan’s cousin) as a vice president of Phrae PAO. Subsequently, Mr.Pongsawat Supasiri (Ms. Siriwan’s younger brother) who was chairman of Phrae PAO council, hindered one of Dr. Charnchai’s projects, i.e., a 120 million loan from Krung Thai Bank.

It is worth noting that Dr. Charnchai had switched sides from the old party and voiced support for the People Power Party (PPP) (พรรคพลังประชาชน), a new rendition of the Thai Rak Thai party (TRT) (พรรคไทยรักไทย). In fact, he had successfully gathered all the opposition votes from council members to join his political group, ‘Hug Muang Phrae’ (กลุ่มฮักเมืองแป้). As a result, Phrae PAO council gained a majority vote for the dismissal of Mr. Pongsawat as chairman. Dr. Charnchai also ordered the remove of a campaign banner with a photo of Ms. Sawit on it. As such, there is a strong reason to believe that she was threatened by the loss of political power and status.

After the murder of Dr. Charnchai, Phrae PAO leaders were replaced for the first time in ten years. Since then, Ms. Siriwan and Mr. Pongsawat have failed to be elected into any local political positions. 4 Even though they had never been charged, in society’s eyes they were guilty by association. It shows that although decentralization of power has not been able to eliminate political violence, society, through an election, has the power to choose whom they see fit for the political job and reject those who have a questionable or violent track record.

As for the court case, after a lengthy process, in November 2015 the Supreme Court of Thailand sentenced two defendants, the gunman and the motorcycle driver, to life imprisonment. Meanwhile, the civil court dismissed all charges for other defendants, included Mr. J (Ms. Siriwan’s cousin) citing not enough evidence to prove involvement beyond a reasonable doubt.

During the late 19th and the mid-20th centuries, Phrae’s economy was very much shaped by the competition for natural resources such as land, wood, tobacco and wolfram. These resources enabled the major political families to grow rich. Members of these wealthy and influential families were usually known as ‘Paw Liang,’ (พ่อเลี้ยง). It means someone who was rich, powerful, had many followers, and often got involved in violence (as being fearless) to obtain respect from the people.

It is worth noting that the death of Dr. Charnchai occurred only two months before the general elections. This case shows that political conflict does not necessarily only occur at the national level. Political conflict and assassinations take place at the local level where there is personal and business conflict. Conflict between politicians from the same party, not just conflict between political opponents, could develop and become violent. Although it is hard to clearly identify what really caused the assassination (as usually there is more than one reason), we could not rule out the background of economic competition.

Nuttakorn Vititanon

Lecturer at School of Law

Mae Fah Luang University, Chiang Rai, Thailand

This paper is a part of the author’s Ph.D. dissertation on “Conflict and Violence of Local Politics in the Upper North of Thailand (A.D. 2000-2009)”, submitted at Mae Fah Luang University.

Notes:

- The word ‘assassination’ is used interchangeably with ‘murder’. In Thai language, the word ‘assassination’ (การลอบสังหาร) means surreptitiously kill someone, which is obviously different from English meaning. Primary information is collected from (1) the domestic newspaper, Thairath, between 1 January 2000 and 31 December 2009. This source is accessible in the National Library of Thailand (2) two online databases which are the Matichon e-library and online news clipping. Sub-district headmen and village headmen are not included into the definition of ‘Local politician’ in this study as well as the ones who had previously been in that position. ↩

- It was a year in which Thailand had extremely high murder case numbers. The number of homicides usually ranged between 4,000-5,000 cases, but in 2003 the number raised to 6,434 cases. See: http://statistic.ftp.police.go.th/ dn_main.htm (accessed on 16 July 2010) ↩

- In 2004 there were 1,843 times of recorded cases of violence and 1,703 times in 2005. See more in: Srisompob Jitpiromsri, Khwamrunraeng Cheng Krongsang Khwanrunreng Nai Jangwat Chaydantai Sathanakan Khwamrunreng Nai Jangwat Chaydan Paktai Nai Rob Song Pee (2547-2548) [Structural violence of violence structure in the Southern provinces of Thailand, the unrest situation in the South during two years (2004-2005)], ศรีสมภพ จิตร์ภิรมย์ศรี, ความรุนแรงเชิงโครงสร้างหรือโครงสร้างความรุนแรงในจังหวัดชายแดนใต้ สถานการณ์ความรุนแรงในจังหวัดชายแดนภาคใต้ในรอบ 2 ปี (พ.ศ.2547-2548), Deep South Watch Network. Available online: http://www.deepsouthwatch.org/node/16 (accessed on 22 December 2009) ↩

- In 2011, Ms. Siriwan obtained a seat under the party-list proportional representative system (as the votes came from the whole country), but not as an MP from Phrae province. ↩