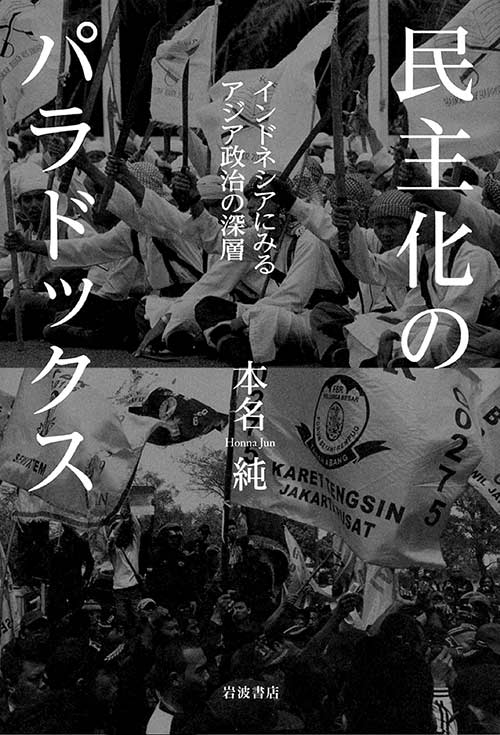

Jun Honna, Paradox of Democratization: The deep structure of Asian politics from Indonesian case

Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten. 2013

Original title in Japanese: 民主化のパラドックスーインドネシアにみるアジア政治の深層

Reviewed by Akiko Morishita

The book begins with Honna’s real experience during his fieldwork when he interviewed a lawyer on local political corruption in post-Soeharto Indonesia. The lawyer, an anti-corruption NGO leader in Central Java, rattled away details of corruption at provincial level for about an hour. After that, however, he intimidated Honna by asking for “information fee” payment. As such, it became clear to Honna that the lawyer is also a local gangster, who gathers information on political scandals and uses it to extort money from politicians and bureaucrats.

[pullquote]In Indonesia, informal violence actors have expanded their influence under the shadows of democratization.[/pullquote]This opening story, as Honna suggests, is just the tip of the iceberg. In contemporary Indonesia, such “non-democratic” forces, specifically informal violence actors (preman), have expanded their influence under the shadows of democratization. This book brings intriguing stories of the democratization process from political and military eyes. Such in-depth understanding on the structure of Indonesian politics has rarely found space in the Japanese media although for Japan, Indonesia is a significant country in terms of economic and international relations. Japanese media usually superficially focuses on topical issues including terrorism, communal conflicts, poverty and a change leadership or government. To a wide audience of Japanese readers, it provides a good insight into the dynamics of politics and violence in one of Japan’s important trading partner within the ASEAN region. Such information, as Honna wishes, may be useful for consideration in shaping practical and meaningful relationship between Japan and Indonesia.But more than that, Honna analyzes what lies behind this “paradox of democratization” in post-Soeharto Indonesia by examining what is the reality of democratization and what lies beneath democracy in Asia. With this, he takes the approach of area studies to dig deep into Indonesian politics and military by his longstanding on-site observation and the extensive interviews he had with prominent Indonesian figures, ranging from top national politicians to national military commanders and influential preman leaders. This alone is a significant step as many Japanese researchers find it difficult to take such approach in studying Indonesian politics.

As shown in the book’s contents, Honna examines six phases of post-Soeharto politics:

- The ending process of New Order period

- The purpose and political consequences of democratic reform

- Power struggle among political elites in the transitional period of democratization (1998-2004)

- Another power struggle among political elite in the established period of democratization (2004-present)

- Security and democratization seen from separatist movements, terrorism, and communal conflicts

- The “underworld” and democratization.

Honna’s focus on the military institution shows how military figures are (still) the key political players in all the six phases of post-Soeharto Indonesia. It informs readers that the relationships between the military and the president as well as internal rivalry within the military have been a critical factor in shaping Indonesian political history and current political situations in most cases. This may not surprise global experts studying Indonesian politics and its military but may provoke the thoughts of its Japanese readers who are interested in Indonesia in many ways.

Honna’s focus on the military institution shows how military figures are (still) the key political players in all the six phases of post-Soeharto Indonesia. It informs readers that the relationships between the military and the president as well as internal rivalry within the military have been a critical factor in shaping Indonesian political history and current political situations in most cases. This may not surprise global experts studying Indonesian politics and its military but may provoke the thoughts of its Japanese readers who are interested in Indonesia in many ways.

The best part and the true value of this book is in its conclusion. Here, Honna takes away the value judgment from the fact that Indonesian politics and security after democratization are managed based on collusion and “mutual assistance (gotong royong) among a small number of elites mainly consisting of the same old faces of Soeharto’s New Order period. He convincingly argues that the reason why in Indonesia democratization could be established and politics and society are stable in broad terms, is precisely because the problems in the old regime remains unsolved in the Reformasi period. Specifically, there is a room for political elites who have vested interests of the old regime to enjoy the political game of democracy, and thus the old elites rarely have motivation to destroy the new system. As a consequence, Indonesian democratic system is somehow sustained and stable today. Readers may see the light with this “paradox of democratization.” Honna suggests that the stability does not have conflict with a situation where the old problems remain unsolved and they are two sides of the same coin. In this point, such conclusion transcends the dichotomy between “democratic” and “non-democratic,” a norm influenced by modern Western political thought that tends to oversimplify in evaluating the quality of democracy in (developing) countries.

From such a point of view, Honna offers a meaningful approach to support the development of democracy in Indonesia. That is, we should not blindly agree with global business actors and policy makers from the West emphasizing a great deal on democratization and political stability in Indonesia for their own reasons. Rather, we should support or at least not disrupt the players who are really trying to improve today’s poor grade of democracy in Indonesia. It reminds us that the true reformists are a minority but can be seen and counted upon in the bureaucracy, political parties and civil society of Indonesia.

After going through this book, readers may envision two questions. One is about the future relationships between Indonesian people and the state, and the other is the different layers of Indonesian politics. The first question is whether Indonesian political system of collusion and power-and-interest sharing among a small groups of political elites will remain unchanged whoever become the President. If so, Indonesian voters may be disappointed every five to ten years because the President, whom the voters have elected with full of expectation to bring about social, economic, and political improvement to the country, would chose political stability rather than real political reform and show poor performance of solving the old political problems until the end of his term. Will Joko Widodo, the newly elected President of Indonesia, end up just like previous presidents disappointing people at some point in their terms? If the trend continues, people’s distrust of the government and its leaders would be more and more critical. The proliferation of distrust and cynicism might lead to another crisis or chaos disrupting the unity of the Indonesian nation-state.

The other question is whether there are other forces and players – apart from the political elite and the military – who had shaped Indonesian political history and influencing the current political trend. While the political elite and the military have been influential in politics, how about the real money holders and conglomerates or big businesses in Indonesia? Have they merely followed the leaders in power after democratization or are they among the unseen power players? Inside stories from the viewpoints of large domestic and foreign companies in Indonesia may show different faces of Indonesia’s democratization processes. Possibly, another layer of the deep structure of Indonesian politics may emerge as the next frontline for young Japanese researches to explore.

Akiko Morishita

(Kyoto University)

Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia. Issue 16 (September 2014) Comics in Southeast Asia: Social and Political Interpretations