2000年に入ってから、漫画について批判的な視点や学問的観点から注目が予想以上に集まっている。明らかに、より大きな三つの流れがこの背景には存在している。一つ目は、ほぼ無制限な市場経済の拡大であり、消費主義や新たな類の「ポップカルチャー」もこれに含まれる。二つ目は、グローバル化の過程であり、これは例えば白石さやによると (2013: 236-237)、日本のマンガやアニメが特定の作品としてよりも、他の社会に応用可能な文化産業のモデルとして、世界的な規模で普及している事に現れている。三つ目が、情報社会の出現により、参加型で流動的な文化の形態が脚光を浴びるようになった事であり、これについてはファンアートやコスプレ、ソーシャルネットワーキングサービスなどを挙げておけば十分であろう。全く驚くべきことに、漫画が一般に認められたのは、基本的に従来の活字メディアによって形成された漫画のアイデンティティに崩壊が生じた、ちょうどその時であった。

こうした流れが、メディア研究や文化人類学、社会学、さらにその他の分野における、マンガ関連の研究を推し進めてきた。この点について、ある東アジアと東南アジアのポップカルチャーの編著本の序章には、次の事が誇らしげに述べられている。「学会であるテーマが妥当かどうかを示す基準の一つは、経済学者や政治学者たちが、これをいつ重視するようになるかである」(Otmazgin & Ben-Ari 2013: 3)。大抵、このような権威付けが意味するのは、マクロ分析の方が入念な個々の事例のクローズアップよりも好まれるということである。せいぜい、漫画はこれといったメディア特有の属性を持たぬ、単なる一次資料の役割を果たせば良いということになる 1。しかし、このような傾向は、政治学の分野それ自体よりも、過去十年間の学術研究の変化に負うところが大きいようだ。上記の本より40年前、Benedict Andersonは、インドネシアのアニメと漫画を用いて、インドネシアの政治的コミュニケーションの研究を行っていたが、これは今日でも驚くほどに洗練された手法であった。「形式は内容と同じ程度にものを言う」(1990: 156)などの基礎前提や、娯楽的な続き漫画は、一コマの政治漫画とは違い、研究者が「形式に目を向け、しかる後に内容を見る」事を要するという見解は、決して時代遅れなどではない。むしろ、特に現代の地域研究で漫画を使う有効性を示している。日本研究は、近年のマンガと関連メディアの有効性を示している点で先を行く。ここでの主流は、漫画研究をポップカルチャーや社会科学の分野に割り当てる傾向で、テキスト分析やヴィジュアル吟味、その他の美学的考察は大抵が無視されたままである。アメリカやヨーロッパの漫画は、「グラフィック・ノベル」という名のもと、あちらの文学部で学術的に考察される一方、特に日本のマンガ、より一般的にはアジアのマンガは、このような学術的取り組みの価値が無いかのようにみなされている。

しかし、この特集号の諸論文は、必ずしも、ある地域研究の枠組みに依拠しているわけではない。ここに掲載された論文は、東南アジア研究を優先させるというより、漫画とその研究に関する論文である。これらが東南アジア研究に貢献できぬと言うのではなく、ただ、そのような貢献が漫画研究を介して行われるという事だ。その意味をここで手短に述べておいた方が良いであろう。

世界的な規模で、漫画研究は、英語、フランス語、日本語、あるいは、アメリカン・コミックス(アメコミ)、バンド・デシネ、マンガといった地政学的、言語学的に明確な文化に応じて枝分かれしており、興味の大半は英語、フランス語、日本語の漫画である。東南アジアの漫画に焦点をあてるという本号の試みは、まだ、かなり例外的なものである。通常、漫画文化の研究は、北アメリカ、西ヨーロッパと日本の比較が中心で、時折、特に日本のマンガについては、韓国や中国語の市場の比較もこれに含まれる 2。この偏重ぶりは、インドネシアと日本の漫画プロジェクトにもあらわれた。これは2008年に国際交流基金(ジャパン・ファウンデーション)が二カ国間の国交50周年を機に後援、実施したものである 3。この成果であるDarmawan とTakahashiの編集による短編集は、当初、両国の言語で出版される予定であったが、日本語版はついに実現せず、日本人のマンガ評論家や読者たちが、インドネシアと日本の両国に起源を持つ非マンガ形式の漫画について学ぶことができなかった。

本号では、東南アジアにおける「マンガ」の役割だけに着目しているわけでもない。焦点はむしろ、漫画の多様性にあり、その範囲は自伝的物語から、絵日記、エッセーのようなブログ上の書き込み、教育向けの作品(歴史教育や性教育に関するものも)、さらには娯楽的フィクションに及ぶ。興味深いことに、紹介された作品例の大半が、もはや「日本の」、「インドネシアの」、「ベトナムの」、といった文化によって分類できるような範疇には当てはまらぬものである。それどころか、さまざまな形でフュージョン・スタイルと呼ぶべきものに広がっていることが特徴的である。さらには、一方では商業的で、型通りで、ファン本位のものとしての「マンガ」があり、もう一方には個人的で、創造力に富んだグラフィック・ナラティブとしての「同人誌」があるという差別化が東南アジアの漫画には必ずしも当てはまらないということが示唆される。おおよその場合、西洋的、日本的観点からも相互に排他的であると見なされているこの二つの種類が、文化的、経済的状況に関する限り、多くの共通点をもつように見えるのである。マンガであれ同人誌であれ、作家達が、少なくとも、それだけで生計を立てることは不可能なのである。

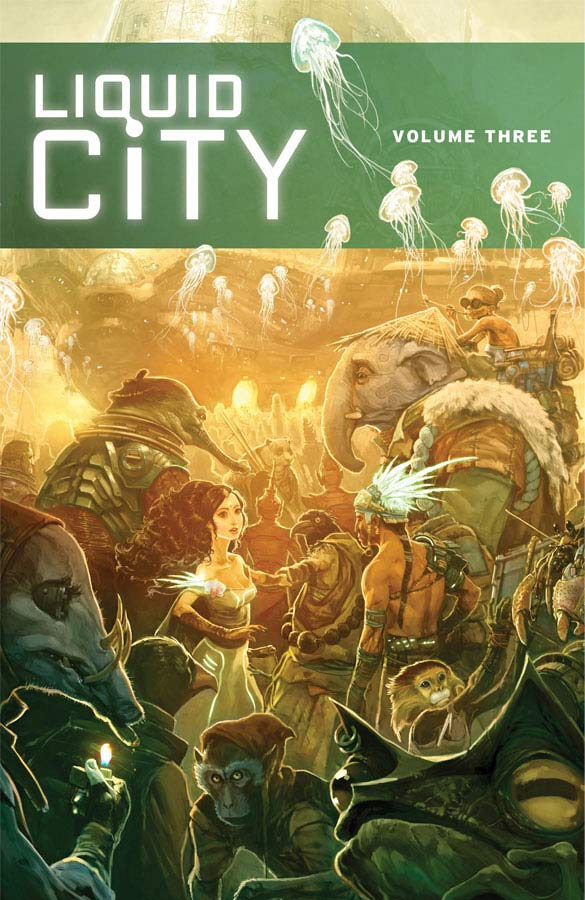

近年では、東南アジアの若手研究者で、大抵が日本を拠点にマンガ研究に携わる者達が、自分達の地域の漫画に注目し、これらを日本語で批判的に紹介しようと懸命に努力している 4。すでに1990年代の後半には、アメリカで教育を受けた文化人類学者で、インドネシアの専門家である白石さやがこの分野に着目しており、初めは日本マンガの普及について、しかし程なくして、現地の漫画文化についても関心をもつようになった。2013年に彼女の論文集が日本語で出版されたことから、彼女の初期の取り組みを再発見し、今日の方法論的問題と関係付けて読みなおすことができるであろう。同様に、特筆しておくべきことは、ベテランの漫画歴史家John Lentが、1999年から、“The International Journal of Comic Art (IJOCA)”という雑誌を世界中のアニメやグラフィック・ナラティブに関する記事のために提供してきたことである。これらの筆者たちの中には、彼の最新巻“Southeast Asian Cartoon Art (2014)”に寄稿した者もいる。これらの評論的、学術的試みに加え、重要な漫画名作選についても、最後に触れておこう。“Liquid City”は、ちょうどその第3巻が出版されたところである(Liew 2008, Liew & Lim 2010, Liew & Sim 2014)。各巻は東南アジアの漫画家たちによる12話以上の短編作の英語翻訳からなる。この名作選のおかげで、(第2巻に対して)アイズナー賞が与えられていなくとも、いかなる漫画研究も、その動機が政治科学や社会学、あるいは美学的な関心であっても、結局は、作品が読めるかどうか次第なのだということがよくわかった。

ジャクリーン・バーント(Jaqueline Berndt)

京都精華大学大学院マンガ研究科・教授

Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia. Issue 16 (September 2014) Comics in Southeast Asia: Social and Political Interpretations

Selected Publications

Anderson, Benedict R. O’G, 1973, “Cartoons and Monuments: The Evolution of Political Communication under the New Order”, id., Language and Power: Exploring Political Cultures in Indonesia, Ithaca, (New York: Cornell University Press, 1990), pp. 152-193.

Berndt, Jaqueline. 2010, ed. Sekai no komikkusu to komikkusu no sekai [Comics Worlds and the World of Comics] (Global Manga Studies, vol. 1), Kyoto: International Manga Research Center, ed., pp. 5-15; [bilingual edition, 2 vols, English and Japanese <http://imrc.jp/lecture/2009/12/comics-in-the-world.html]>

_____2014. “Manga Studies #1: Introduction,” Comics Forum (academic website for Comics Studies, Leeds University), 11 May 2014 [3000 words] <http://comicsforum.org/2014/05/11/manga-studies-1-introduction-by-jaqueline-berndt/>

_____2014, ed. Nihon manga to “Nihon”: Kaigai no sho komikkusu bunka o shitajiki ni (Kokusai manga kenkyū 4) [Japanese manga and “Japan,” seen from the perspective of the respective comics cultures abroad], Kyoto: International Manga Research Center.

Cheng Chua, Karl Ian Uy, and Kristine Michelle Santos, “Firipin komikkusu no ‘shi’ nitsuite” [The “Death” of Philippine Komiks], in J. Berndt, 2014, pp. 159-180.

Darmawan, Ade and Takahashi Mizuki, eds, Kaldu Ikan: komik Indonesia + Jepang (comics anthology, in Indonesian), (The Japan Foundation, 2008).

Gan, Sheuo Hui, “Manga in Malaysia: An Approach to Its Current Hybridity through the Career of the Shojo Mangaka Kaoru,” in Ōgi, Fusami, J. Berndt & Cheng Tju Lim, “Women’s Manga beyond Japan: Contemporary Comics as Cultural Crossroads in Asia,” IJOCA, vol. 13, no. 2 (Fall 2011), pp. 164–78.

Goethe Institut Jakarta, 2012-2013. City Tales (Comics Blog) <http://blog.goethe.de/CityTales/pages/about_E.html>.

_____2014. City Tales (book edition, only available via Goethe Institut).

Kusno, Abidin, “Master Q, Kung Fu Heroes and the Peranakan Chinese: Asian Pop Cultures in New Order Indonesia,” in Otmazgin & Ben-Ari, eds, 2013, pp. 185-206.

Lent, John, ed., 1999, Themes and Issues in Asian Cartooning: Cute, Cheap Mad, and Sexy, Bowling Green: Bowling Green State U Popular P.

_____2001, Illustrating Asia: comics, humor magazines, and picture books, (Honolulu: University of Hawaii).

_____2004. Comic art in Africa, Asia, Australia, and Latin America through 2000: an international bibliography, (Westport CT: Praeger).

_____2011. “Cambodian, Vietnamese Comic Art: A Symposium,” IJOCA, vol. 13, no. 1 (spring), pp. 3-108.

_____2014, ed. Southeast Asian Cartoon Art: History, Trends and Problems, (Jefferson, NC: McFarland).

Liew, Sonny, Liquid City Volume 1, (Berkeley: Image Comics, 2008).

Liew, Sonny, and Lim, Cheng Tju, eds, Liquid City Volume 2, (Berkeley: Image Comics, 2010).

Liew, Sonny, and Joyce Sim, Liquid City Volume 3, (Berkeley: Image Comics, 2014).

Lim, Cheng Tju, 2010. “Lest We Forget: The Importance of History in Singapore and Malaysia Comics Studies,” in J. Berndt 2010, pp. 187-200.

_____2013. “Singapore Comics,” IJOCA, vol. 15, no. 1 (spring), pp. 723-733.

Otmazgin, Nissim, “Popular Culture and Regionalization in East and Southeast Asia,” in Otmazgin and Ben-Ari, eds, 2013, pp. 29-51.

Otmazgin, Nissim, and Eyla Ben-Ari, eds, Popular Culture Co-productions and Collaborations in East and Southeast Asia, Kyoto CSEA Series in Asian Studies 7 (Singapore: NUS Press, in association with Kyoto University Press, 2013).

Otmazgin, Nissim, and Eyla Ben-Ari, “Introduction: History and Theory in the Study of Cultural Collaboration,” in Otmazgin and Ben-Ari, eds, 2013, pp. 1-25.

Shiraishi, Saya. 1997. “Japan’s Soft Power: Doraemon Goes Overseas,” Peter Katzenstein & Takashi Shiraishi, eds, Network Power: Japan and Asia, (Cornell University Press), pp. 236-249.

_____2013. “Umi o koeta Doraemon, id. Gurōbaruka shita nippon no manga to anime, Tokyo: Gakujutsu shuppan, pp. 19-27.

_____2013. Gurōbaruka shita nippon no manga to anime, (Tokyo: Gakujutsu shuppan).

Sihombing, Febriani, “Komikku o ‘seijika’ suru ‘eikyō’ron to ‘yōshiki’ron—Indoneshia no komikku gensetsu nitsuite” [The ‘Politicization’ of Comics by ‘Influence’ and ‘Style’: On Comics Discourse in Indonesia], in J. Berndt, ed., 2014, pp. 59-84.

ojirakarn, Mashima. 2014. “Tai komikkusu no rekishi: Tayō na manga bunka no aida de keisei sareta hyōgen” [A History of Thai Comics: Formation of Style in-between a Comics Cultures], in J. Berndt, ed., 2014, pp. 85-118.

_____2011 “Why Thai Girls’ Manga Are Not ‘Shōjo Manga’: Japanese Discourse and the Reality of Globalization”, in Ōgi, Fusami, J. Berndt & Cheng Tju Lim, “Women’s Manga beyond Japan: Contemporary Comics as Cultural Crossroads in Asia,” IJOCA, vol. 13, no. 2 (fall 2011), pp. 143–63.

Notes:

- Indicative of the trifling with one particular sort of comics, i.e. manga, is, for example, the unawareness of already established titles: Hana yori dango is globally not known as “Men are better than flowers” (Otmazgin 2013: 39) but “Boys over flowers;” likewise symptomatic is the wrong spelling of “Crayon Sinchan” [correct: Shinchan] (Kusno 2013, passim). ↩

- The long disregarded role of Chinese-language media products for the recent spread of Japanese manga culture has been pointed out by Kusno (2013) and also Shiraishi (2013: 82-83). ↩

- Under the general title Kita! Japanese Artists Meet Indonesia, the following comics artists participated: Agung Kurniawan, Beng Rahadian, Dwinita Larasati, Eko Nugroho, Kondoh Akino, Nishijima Daisuke, Oishi Akinori, Shiriagari Kotobuki. ↩

- See Cheng Chua & Santos (2014), Gan (2011), and especially noteworthty, doctoral candidate Febriani Shihombing (2014), and Mashima Tojirakarn (2011, 2014). ↩