Between Malaysia’s 14th general elections in May 2018 and December 2021, Putrajaya saw a change of three prime ministers and the collapse of two ruling coalitions. As a result, the office of the foreign minister rotated thrice between two appointments and the country’s defence portfolio was led by three different ministers, consecutively. In the background, the onset of the COVID-19 health and economic crises exacerbated the domestic landscape.

During that timeframe, too, Malaysia released its first ever defence white paper and two foreign policy frameworks articulating the country’s priorities and position in the conduct of its external relations. This essay argues that despite the domestic political upheaval and episodic missteps in its external ties over the last four years, Malaysia’s broad foreign policy underpinnings remain unchanged in substance. The conduct of personality-driven foreign relations may have contributed to an air of policy incoherence but the precepts of Malaysian diplomacy have been consistent. However, moving ahead, the staying power of new focus areas such as health diplomacy, cybersecurity, and cultural diplomacy will depend very much on the country’s internal stability, leadership, and resource prioritisation.

One Step Forward: Precepts and Policies

The political turmoil in Malaysia was unprecedented for a country that had, until 2018, been helmed uninterrupted for nearly six decades by the Barisan Nasional (National Front) government. The ramifications of backroom party manoeuvres that resulted in the unseating of the elected Pakatan Harapan (Alliance of Hope) coalition in 2018 and that then triggered a series of political implosions continue to roil below the surface.

A memorandum of understanding on transformation and political stability between the federal government and coalition of opposition parties is the only instrument keeping the partisan peace until the next general elections are due upon the dissolution of the 14th session of Parliament in July 2023. Yet, this truce notwithstanding, Malaysia’s domestic environment remains highly politically-charged with state elections at the end of 2021 seen as priming the pump for the nation’s 15th general elections. As such, a sense of uncertainty about the endurance of Malaysia’s policies prevails.

In September 2019, a little over a year after the Pakatan Harapan government was voted in with promises of a Malaysia Baharu (New Malaysia), Malaysia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs released its, “Foreign Policy Framework of the New Malaysia” (“2019 Framework”) titled, “Change in Continuity.” Three months later, the Ministry of Defence tabled Malaysia’s first ever comprehensive defence white paper (DWP) to Parliament for approval. In outlining the contours of Malaysia’s foreign and defence posture, these documents affirm long-standing fundamentals: inclusive internationalism, non-alignment, non-intervention, peaceful settlement of disputes, and the rule of law. Both also make clear that the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) will remain the cornerstone of Malaysia’s foreign policy.

Strikingly, the documents are a product of their time. In aspiring to better respond to the evolving realities of Malaysia’s strategic environment, the 2019 Framework and the DWP reflect the optimism of a nation that then seemed to be turning a corner with a change in government. Both documents were the result of a consultative process that included non-government stakeholders. The 2019 Framework pledges proactivity and prominence on the international stage. It speaks of advocating human rights, protecting sovereignty, and recognising non-traditional security challenges such as migration, cybersecurity, and terrorism. The DWP, on the other hand, sketches a plan for an integrated, agile, and focused future force that would more effectively defend Malaysia’s position as a “maritime nation with continental roots”. It proposes a new approach to defence science, technology, and industry in the country. The DWP was envisioned as “another element [to] enhance Malaysia’s geopolitical profile.”

Two Steps Back: Inconsistencies amid Continuity

In February 2020, the Pakatan Harapan government unravelled, the Perikatan Nasional (National Alliance) coalition led by Muhyiddin Yassin came into power, and COVID-19 upended the world. The Framework and DWP documents effectively went into abeyance. Yet, the axioms upon which they were built persisted even if Malaysia’s foreign policy execution appeared to lack coordination or consistency, at times. This incoherence seemed particularly pronounced in response to Beijing’s provocations to Malaysia’s claims in the South China Sea and with the announcement of the trilateral Australia-United Kingdom-United States (AUKUS) arrangement.

As Malaysia battled the first wave of the pandemic in the first half of 2020, it also had to deal with intimidation of its contracted oil exploration vessel, West Capella, by the Chinese survey vessel, Haiyang Dizhi 8, in the South China Sea. The United States and Australia sent warships to the area to signal presence and capability. The move may also have been intended as a gesture of support for regional partners but Malaysia’s then-foreign minister, Hishammuddin Hussein, distanced Putrajaya from the US’ response. Cautioning against the potential of increased tensions from “warships and vessels” in the South China Sea, the minister’s remarks appeared to have equivocated the escalatory effect of both Chinese ships, on the one hand, and US and Australian vessels, on the other.

As others have pointed out, to avoid any misunderstanding, Malaysian policy elites should have made it clear that the statement reflected the government’s continuation of its equidistant policy from major powers since the early 1970s. 1 Putrajaya’s anxiety relates to US-China rupture changing the nature of the South China Sea dispute from one of regional overlapping claims to major power contestation. It should have communicated this better. The perception of Malaysia associating with China’s narratives on the region was not helped by Hishammuddin’s gaffe a year later when he used the term, “elder brother” in a joint media conference with Wang Yi, China’s State Councillor and foreign minister. As a result of heavy criticism by Malaysians on social media, Hishammuddin clarified that, “Malaysia remains independent, principled, and pragmatic in terms of our foreign policy” and that his “elder brother” phrase was a personal reference to Wang Yi’s relative seniority rather than any indication of bilateral ties between Malaysia and China.

A year later, on the 47th anniversary of Malaysia-China relations, 16 People’s Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF) planes flew in tactical formation close to Malaysia’s national airspace over the South China Sea. Unusually, both the Royal Malaysian Air Force (RMAF) and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs issued their own media statements with the latter basing theirs on the former’s. The RMAF’s detailed incident report was carefully worded. It noted that the planes entered the “airspace of Malaysia’s Maritime Zone, Kota Kinabalu Flight Information Region and neared [italics author’s own] Malaysian airspace.” The statement also made mention of the aircraft posing a “threat to [Malaysia’s] national sovereignty and flight safety.” By contrast, the ministry’s reference to “this breach of the [sic] Malaysian airspace and sovereignty,” implied an actual rather than a threatened violation of national airspace. China’s confrontational act was never in any doubt nor was Malaysia’s disposition to defend its territory (the RMAF scrambled its jets in response). However, closer coordination with counsel in the drafting of the ministry’s statement after the incident would likely have led to a more legally accurate statement and improved public alignment between the two agencies.

Malaysia’s aversion to entanglement in great power politics in its own backyard was further evinced by the government’s response to the announcement of AUKUS in September 2021. Ismail Sabri, the country’s ninth prime minister, sworn into office only a month earlier, expressed concern about AUKUS’ impact on stability in Southeast Asia. Saifuddin Abdullah who, in Ismail’s cabinet, returned to the foreign affairs portfolio that he had led under the Pakatan Harapan government, released a statement in support of the prime minister’s position. Hishamuddin Hussein, who reassumed his leadership of the defence ministry, did the same. All three statements reiterated the risks of a conventional and nuclear arms race, particularly in the South China Sea. Saifuddin further underscored Putrajaya’s disquiet alongside Jakarta’s in a joint press conference with his Indonesian counterpart, Retno Marsudi.

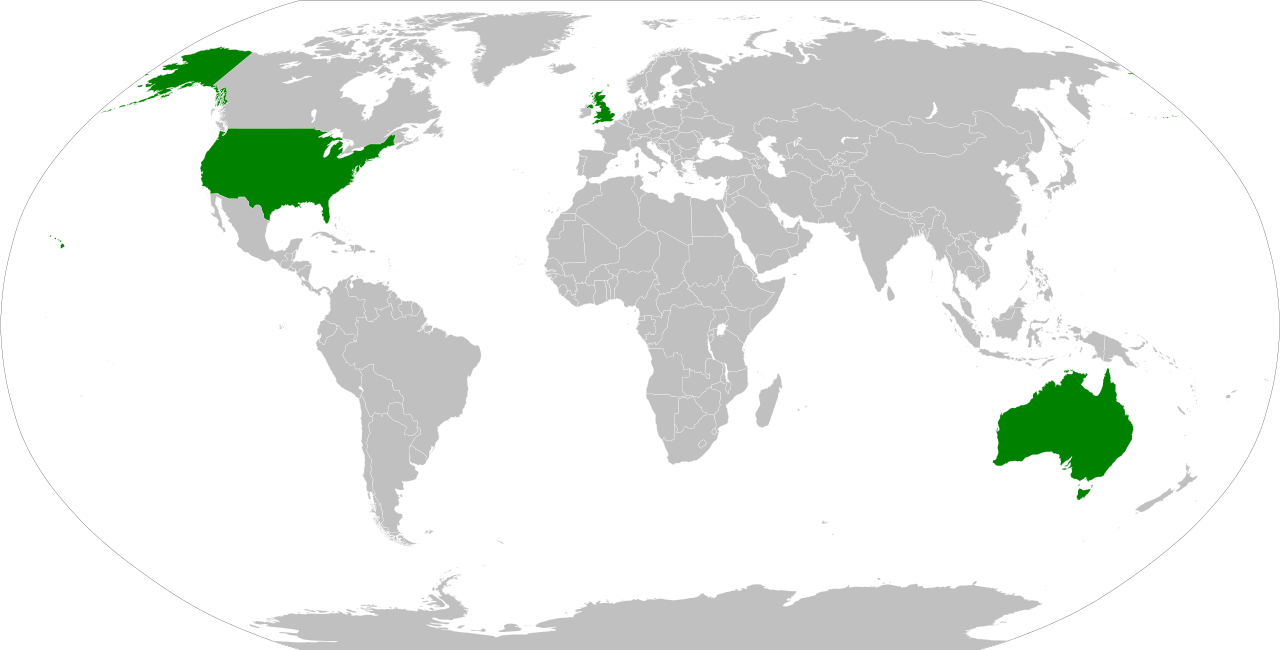

Despite Malaysia’s reservations about AUKUS, the government has welcomed deeper relations with all three countries in the security pact, bilaterally and multilaterally through platforms such as the Five Power Defence Arrangements (FPDA). Additionally, although Hishamuddin misspoke about consulting with China on AUKUS (he then walked his statement back), he stressed that Malaysia would “continue with the advantages [in reference to the FPDA] that we have when facing the geopolitical super powers in the region, especially in the South China Sea.” His ministry, in fact, hosted the FPDA’s 50th anniversary celebration and the FPDA ministers’ meeting following a 10-day exercise with Australia, New Zealand, Singapore, and the United Kingdom.

Saifuddin Abdullah’s return to the foreign ministry as part of Ismail Sabri’s government in 2021 revived an earlier focus on human rights. The ministry’s 2019 Framework had sought to take a more active stance on the issue as part of Malaysia’s transformation into a more developed and conscionable nation. But a large part of this sustained interest to advocate for a rights-based foreign policy agenda is attributable to the minister’s own commitment stemming from his days as a youth activist and interactions with grassroots organisations later in his career.

In 2018, Saifuddin urged Malaysian lawmakers to reconsider ASEAN’s non-interference policy with then-specific reference to the plight of the Rohingya. In 2021, the minister reiterated his sentiments with the eruption of the crisis in Myanmar, calling instead for a policy of non-indifference. Saifuddin stood firm in refuting the participation of the Tatmadaw’s Senior General Min Aung Hlaing at the ASEAN Summit in October 2021 unless there was progress on ASEAN’s five-point consensus.

Conclusion: A foreign policy framework for the future?

In December 2021, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs released another foreign policy framework, this time titled, “Focus in [sic] Continuity: A Framework for Malaysia’s Foreign Policy in a Post-Pandemic World” (“2021 Framework”). Meant as an extension to the 2019 Framework, the document affirms Malaysia’s foreign policy fundamentals but aims to “provide fresh impetus, focus, and direction” especially in the aftermath of COVID-19. Like the 2019 Framework, the updated version restates non-alignment, international law and norms, and human rights as enduring principles. As with the earlier iteration, the 2021 Framework was prepared in consultation with non-government stakeholders. It reemphasises cybersecurity as a focus issue but adds to the list Malaysia’s links to the global economy, health diplomacy, the digital economy, cultural diplomacy, peaceful coexistence, multilateralism, and the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals of 2030. Each of these areas is elaborated upon in terms of foreign policy objectives and implementation.

Given the volatility of Malaysia’s domestic situation, the 2021 Framework allays questions surrounding the country’s immediate foreign policy imperatives. However, it is also precisely because of the shifting plates of Malaysia’s political landscape that there remains uncertainty over the durability of the 2021 Framework in its entirety. Priority areas such as peaceful coexistence and multilateralism are, by their nature, longer-term objectives that can and will endure political capriciousness. Moreover, as part of the larger bureaucratic engine, Malaysia’s career diplomats serve professionally regardless of political leader and have offered functional stability amid the ongoing partisan flux.

However, in order to advance a progressive foreign policy agenda, emerging areas such as the digital economy as well as health, cultural, and cyber diplomacy will require a cultivation of specialised skill-sets, lateral cross-cutting knowledge, and concerted, inter-agency coordination. These areas will, in turn, necessitate sufficient resource allocation, institutionalised capacity, and focused political resolve. Malaysia’s foreign policy fundamentals are sound enough for auto-pilot conduct, if necessary. But the basics are no longer enough in an increasingly complex world. As the DWP and foreign policy frameworks themselves recognise, Malaysia must be proactive and entrepreneurial in its outreach. Unless the domestic political erraticism abates, however, the country’s international agenda may not advance beyond the rudimentary. Foreign policy is, after all, but an extension of domestic policy. To get it right outside, Malaysia must first get it right at home.

Elina Noor

Elina Noor is Director, Political-Security Affairs and Deputy Director, Washington, DC office, Asia Society Policy Institute

Notes:

- C. C. Kuik and D. Thomas, “Malaysia’s Relations with the United States and China: Asymmetries (and Anxieties) Amplified,” Southeast Asian Affairs, forthcoming (2022). ↩