Anan Ganjanapan

Local Control of Land and Forest: Cultural Dimensions of Resource Management in Northern Thailand

Chiang Mai / Regional Center for Social Science and Sustainable Development, Faculty of Social Sciences, Chiang Mai University / 2000

Shigetomi Shin’ichi

Tai noson no kaihatsu to jumin soshiki

(Village organization for rural development in Thailand)

Tokyo / The Institute of Developing Economies / 1996

English edition: Cooperation and Community in Rural Thailand: An Organizational Analysis of Participatory Rural DevelopmentTokyo / The Institute of Developing Economies / 1998

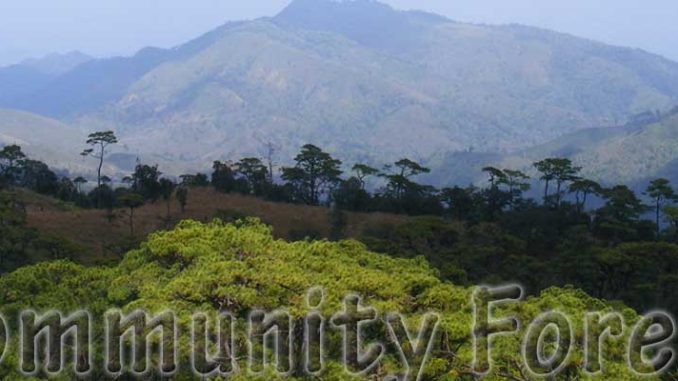

The debate over sustainable forest use in Thailand has recently become intense, with the Royal Forestry Deparment, NGOs, and local communities disagreeing over how best to manage forest resources. Legislation on a Community Forest Bill, initiated in the early 1990s, has still not been enacted. These disagreements are complicated by the power of what John Embree called the “loosely structured,” bilateral nature of Thai society.

Shigetomi Shin’ichi argues that capitalist penetration has not dissolved social unity, but rather encouraged the transition from bilateral relationships to collective cooperation as an adaptation to the market economy. Villages in Northeast Thailand have developed collective organizations like labor exchange groups, funeral ceremony unions, and saving unions. He sees these efforts leading to the formation of local organizations that will manage forest resources under programs sponsored by government and NGOs. He observes that these programs have succeeded where they coincide with natural villages organized around Buddhist temples or guardian rituals. No longer religious, however, the collective organizations are based on economic incentives.

Anan Ganjanapan argues the opposite: that self-sufficient peasant society based on the unity of kinship or community has been destroyed by capitalist penetration and the modern state’s legal institutions and ownership regulations. Efforts to revitalize community forests thus need to restore the “community” and its moral values. Anan suggests that customary regulation of land, forest, and community be thought of not only in terms of economic resources but holistically, as part of a community’s life. He also suggests that sustainable use of natural resources can not be expected without full recognition of local people’s collective rights to resource management.

Where Shigetomi sees the transition of bilateral into community cooperation, Anan sees a community unity that has long managed communal resources. The reviewer points out, however, that such communal traditions have declined, and communities have not been strong enough to maintain management of their resources by themselves. His own research, as well as Shigetomi’s, indicates that successful community organization often depends on a charismatic leader to guide villagers through decision-making and conflict resolution. A combination of communal solidarity and bilateral relations can thus exist.

Finally, the presence of state agents does not have to lead to conflict. In Northeast Thailand, forest officers have worked with NGO activists and community leaders to mediate state-community relations and implement proper forest management.

Fujita Wataru

Fujita Wataru is Junior Research Fellow at the Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Kyoto University.

Read the unabridged version of this article HERE

Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia. Issue 2 (October 2002). Disaster and Rehabilitation