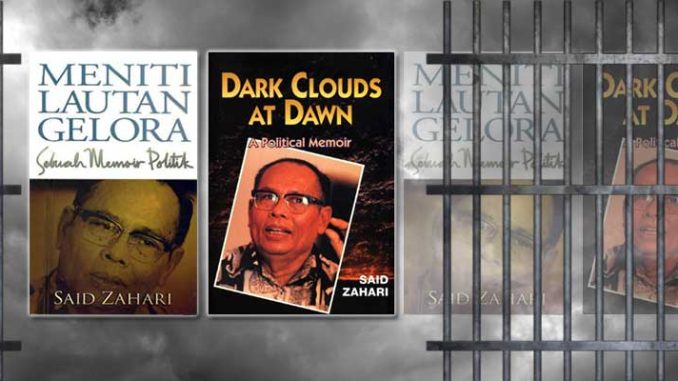

Said Zahari

Dark Clouds at Dawn: A Political Memoir

Kuala Lumpur / Insan / 2001

Said Zahari

Meniti Lautan Gelora: Sebuah Memoir Politik

Kuala Lumpur / Utusan / 2001

Translated and adapted from the remarks of Abdul Rahman Embong at the book launch of Said Zahari’s memoir in Kuala Lumpur in April 2001.

Editor’s Note: Said Zahari was a journalist in the 1950s and 60s, crucial years in which the nature of leadership, public debate, and political participation were institutionalized in the emerging nation-states of Malaysia and Singapore. Born and raised in Singapore, Pak Said wrote for the anti-colonial Malay-language newspaper Utusan Melayu and became its dynamic editor at its main office in Kuala Lumpur in 1959. In 1961, he led the workers of Utusan in a historic 3-month strike to try to preserve its editorial independence from the ruling political party UMNO. As a result, he was banned from Malaya. Moving from journalism into politics, he joined the effort of the multi-dimensional and multi-ethnic left to forge an alternative to the conservative turn of Lee Kuan Yew’s People’s Action Party. On the very night in February 1963 that he joined Partai Rakyat (People’s Party) and was elected to its leadership, he was swept up in the mass arrests of Operation Cold Store. By this means the governments of Singapore and Malaya cleared the way for their (ill-fated) merger as Malaysia. A contemporary of Mahathir bin Mohamad and Lew Kuan Yew, Said Zahari was held without charge for over 17 years.

Usually the appearance of an important new publication promises to shed light on a topic that is unknown or little discussed. In the case Said Zahari’s memoir, we are faced with a different situation. The memoir is being launched today, but the book is already well known and much anticipated. It has been discussed for the past several years in the various language media of Malaysia and Singapore, especially since the publication of a memoir by one senior political leader across the Causeway who was responsible for making Pak Said his “special guest” at Changi and other prisons for about seventeen years – a period Pak Said refers to as “seventeen years of long nights.” Even more noteworthy is that Pak Said’s memoir has been published in three languages – Malay, Mandarin, and English – by three different publishers at about the same time, something extraordinary in the world of publishing in this country or any other.Pak Said’s memoir has drawn such attention for good reason. The public – whether friends or general readers, irrespective of ethnicity – will want to learn about the trials and tribulations of Pak Said’s struggle. A nationalist figure of the left, Pak Said joined Utusan Melayu shortly after World War II, in the period when that newspaper was at the height of its influence as an independent, nationalist, and anti-colonial voice in Malay journalism. He later replaced co-founder Yusof Ishak as editor and led the famous 1961 Utusan strike which resulted in his being banned from Malaya and becoming the “special guest” of the Singapore government. Readers will want to discover his heart’s desires, his experience of struggle, his ideas and world view – particularly how he endured so long despite the thousand thorns along his journey. We want to delve into his soul, to see if he holds personal rancor against those responsible for seizing his freedom and the happiness of his family. We want to know how his wife, Kak Salamah, faced this tempest while suffering from breast cancer and bearing responsibilty for four young children. We want to know the truth about the label “communist” imposed retrospectively upon him by the Singapore government eight years after he was jailed – was it appropriate or a cheap but poisonous label used by the authorities to suppress political opponents in order to remain in power? All of this has been recounted very well in this 374-page memoir.

As readers will learn, Pak Said is an ordinary human being who has been blessed with both life’s bitterness and extraordinary fortitude. Although he was not able to pursue higher education because of the outbreak of World War II, he became fluent in Malay, English, and later on, Chinese, became a journalist renowned for defending press freedom, and led the then largest and most influential newspaper in Malaya and Singapore. Although born into a Malay family and subsequently editor of a Malay press, he built bridges to other ethnic groups, all of whom respected and accepted him. Although he was not a leader of a major political party and did not even become a leading figure in that party, he was much hated and feared by the authorities in Singapore. To my mind, he is a fighter whose principles and struggle for freedom have exacted from him the exorbitant price of being the Malay political detainee with the longest record in detention – almost two decades – an experience that has nevertheless not weakened his resolve at all.

We may ask why someone like Pak Said is moved to write a memoir. The answer is probably quite simple: he has a message to convey, something that comes from his heart and his experience that he wants to share with readers and preserve in the historical record. In my opinion, a memoir is a personal historical statement woven together with national and international history. It is a statement about how national and international history makes an impact on personal history and how the individual responds to that history. The writing of a memoir cannot be faked by making up what is not there or exaggerating what is. Should this happen, the sensitive reader would certainly detect it and feel the lackluster lifelessness of the work. Pak Said’s memoir is far from this. Dark Clouds at Dawn is a memoir that is truly authentic and intense with feeling, written from the viewpoint of “the narrator as actor” (‘yang empunya cerita’). It is a story that belongs to the turbulent age when Malaysia, Singapore, and Southeast Asia struggled for independence against colonialism and imperialism. Reading it informs us not only of one personal history but of a mosaic of events occurring in our homeland, in Singapore, and in Southeast Asia that may previously have eluded us

When we acknowledge memoir to be a genre of historical writing from the perspective of the actor himself, we acknowledge that history is not monolithic, but complex in character, not linear but full of twists and turns. It is not created solely by great figures who are powerful and exalted, but also by those who are victimized, powerless, and branded with all manner of labels. History is filled with protagonists and antagonists, with winners and losers. But the history that is proclaimed and published is often one-sided history of the victors, which treats those who lost with cruelty. And history is sterile when it belongs only to the victors, not taking into account the others who shaped its path. In my opinion, the publication of Pak Said’s memoir and its recognition as a contribution to historical writing will enhance our understanding of our country’s history and of those events and figures whose names we already know well.

The great Indonesian author Pramoedya Ananta Toer wrote in Bumi Manusia (This Earth of Mankind) that “a painting is literature rendered in colors while literature is a painting rendered in words.” Pak Said’s memoir is such a painting in words – beautiful, dynamic, filled with joys and sorrows, will and fighting spirit, comradeship, fortitude, generosity of spirit, optimism, and humility. He faced his life’s troubles without harboring personal vengeance against those who seized his freedom and the happiness of his family. As he explains in his preface, “everything that happens has its causes and effects…. [I]n life, it is decreed that there is hardship in ease, and ease in hardship.” Against this generosity of spirit, those who seized his freedom, who hurled accusations, and especially those who tortured him seem to possess a stunted humanity and small, hollow souls. This impression is lasting, whether or not we agree with Pak Said’s views and interpretations.

Pak Said never went to any university to obtain higher education. But the Changi Prisons and Ubin Island, as well as the struggle at Utusan, were the real “university” from which he “graduated” with distinction. It was only in 1996, at the age of 68 and after suffering a stroke, that Pak Said first officially stepped foot into a university. By this time, he was not a student, but a Guest Writer in the Department of Communications at Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia. It was this sojourn which resulted in this historically significant memoir. UKM deserves commendation for its efforts to establish a Memoir Series under the auspices of UKM Press and for making possible the writing of this memoir. And Utusan deserves credit for publishing it.

The launching of this book today is a sweet moment for Pak Said, his family, and comrades, some of whom are unnamed and unknown. It is also a testament to his role in the history of press freedom and the political history of Malaysia and Singapore more generally. His story, as captured in this memoir, is the crystallization of the intense resolve of an extraordinary figure in an extraordinary time that has now been recorded for our historical nourishment. It is eternally dedicated to all those who gave of themselves in the struggle for freedom, justice, and humanity.

Abdul Rahman Haji Embong

Abdul Rahman Embong is Professor in Sociology of Development and Principal Research Fellow at the Institute of Malaysian and International Studies (IKMAS), Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia. He is a senior member of UKM Editorial Board which oversees UKM Press and was advisor to Pak Said when he was preparing for this memoir during his two-year tenure at UKM. This essay was translated by Muhammad Nadim Adam, with assistance from Sumit K. Mandal and Donna J. Amoroso.

Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia. Issue 3: Nations and Other Stories. March 2003