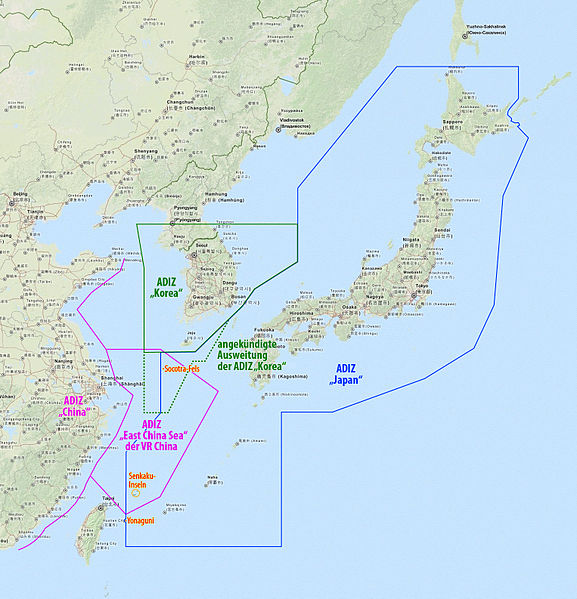

China’s November 23, 2013 declaration of an Air Defense Indentification Zone on the East China Sea, overlapping an area of the Diaoyutai/Senkakus disputed with Japan, has rankled its neighbors, principally Japan and South Korea. It has pushed these countries as well as the United States and Australia to challenge the new rules Beijing imposed, by flying into the declared ADIZ without reporting their flight plan to China or taking unusual steps to identify themselves. In China’s defense, Chinese sources argue that countries have the right to declare ADIZ – as Japan itself declared one in the same area over forty years ago and that the US and about twenty other countries have several such zones that other states respect — and that moreover the move was defensive and in response to Japanese politicians’ threat to shoot down Chinese drones flying over Japanese airspace.

Some observers, including the US Secretaries John Kerry of the State Department and Chuck Hagel of Defense, on the other hand, reacted to the latest Chinese moves by accusing China of an attempt to change the status quo, by extending to air space the contention over maritime spaces that had long fraught relations between China and Japan. The stakes in the maritime disputes include sovereignty, exploitation of the ocean’s living and non-living resources, access to vital sealanes of communication for the claimant-states and other ocean users; for the big powers they involve strategic competition for regional leadership; and additionally on the part of China, a perceived need to set right perceived historical wrongs. The attempt to unilaterally exercise jurisdiction in air space above disputed islands and waters, on the other hand, appears to have created a new object of dispute, with critics seeing the threat to freedom of overflight to be no less significant than how exaggerated maritime jurisdictional claims threaten freedom of navigation at sea.

Freedom of navigation has long been identified by the US as its core interest in the South China Sea, and this was underscored by an incident on December 5 in which a Chinese ship maneuvered close to the USS Cowpens, a guided missile cruiser that China accused of tailing its new aircraft carrier (the Liaoning) which it had deployed to the South China Sea. Defense Secretary Hagel called Chinese actions “irresponsible” and said that the incident could have triggered “some eventual miscalculation”. One problem is that among the still unresolved issues in the Law of the Sea Convention is the interpretation of the provisions regarding the rights of states to conduct military activities at sea, with Chinese and US implementing contradictory policies in this regard. This incident was one more evidence of the two powers’ propensity to challenge each other’s military presence and activities, and is something that can only be addressed through bilateral talks between the two sides.

Closer to Southeast Asia, after the Chinese ADIZ over the East China Sea was announced, there was speculation that China might be considering declaring a similar ADIZ over the South China Sea. Wu Shicun, President of the Hainan-based National Institute for South China Sea Studies, argued that an ADIZ over the South China Sea was not viable – given the much wider area that will need to be covered, China’s lack of legal and technical preparations for doing so considering that it has not clarified its legal claims to the nine-dashed lines, and the number of disputing states that could be affected and whose reaction might impinge on China’s other strategic goals in Southeast Asia. Wu also alleged that unscrupulous Western media outfits stood to benefit by sensationalizing the ADIZ issue and moreover demonizing China by forwarding a baseless claim that China would do the same for the SCS. His stance tries to differentiate China’s approach towards Japan in the East China Sea and towards ASEAN countries in the South China Sea.

However, just this year, China also announced that it was implementing the Hainan Provincial People’s Congress policies requiring ‘foreign fishermen’ operating within the disputed Spratlys or Paracels to seek China’s permission to fish or conduct surveys in areas within Hainan’s ‘jurisdiction’, an area which covers about two thirds of the ocean. Indeed, a similar but stronger announcement by China had been made in late 2012 when it said that it would board and inspect foreign fishing vessels, and other reports claim that the most recent announcement was a reiteration of a thirty year-old law. US State Department spokesperson Jen Psaki has called this latest move to restrict other countries’ fishing activities in disputed portions of the South China Sea “a provocative and potentially dangerous act“.

Objectively, the provisions declared by Hainan would be near impossible to implement when one considers the risks, as the militaries of not just China but at least four other governments operate in the area, and because doing so would raise more accusations against China of blatant violation of its UNCLOS commitments. It is this type of limitation on fishing rights that the Philippines precisely hopes to prevent when it formally filed complaints against China before the International Tribunal on the Law of the Sea (ITLOS). If China implements boarding measures or otherwise prevents normal fishing activities by coastal states even in their own EEZs, it will provide the strongest support for the validity and significance of Philippine claims.

The Philippines – now focused on its legal strategies – has wisely chosen not to over-react and instead sought clarification from China on the meaning of the new measures. Vietnamese fishermen, meanwhile, continue to fish in the Paracels, although there were reports of one incident where Chinese authorities stopped a fishing vessel and confiscated its catch.

As the ADIZ debate flew fast and furious and as affected countries struggled with a response to China’s fishing regulations, a ‘mysterious’ report that China was preparing to invade Philippine-held Pag-asa (Zhongye) island in the year 2014 was published by a Chinese magazine Qianzhan on January 13, a summary of which was published by China Daily Mail under the headline, “China and the Philippines: The reason why a battle for Zhongye (Pag-asa) Island seems unavoidable.” To date, there has been no confirmation from official sources in China that this was true, and other Chinese analysts criticized such a perspective, with some implying that this was someone else’s black propaganda intended to further demonize China.

A specific threat against the Philippines might make sense in the context of the run-up to March this year, when the case filed by the Philippines questioning the legality of China’s 9 dash line will receive its first airing before the ITLOS arbitral panel. This assumes that China sees the abitration case as potentially so damaging to the legitimacy of its territorial and maritime claims that it would resort to such desperate measures as waging war at the cost of abandoning international norms and its avowed political-diplomatic courses of action. However, because the execution of such a threat to use violence would mean loss of life (more likely on the Philippine side, given the firepower asymmetry), and would change the status quo in clear violation of many China-ASEAN confidence-building agreements, the political cost to China’s ties with ASEAN would be too high. So high that commentators, including expert analyst Carl Thayer, have dismissed the report as little more than ‘bravado’.

Setting aside bravado, China’s recent acts of strong assertion of sovereignty as well as promotion of its strategic interests increasingly appear aimed at getting other regional and even extra-regional states to accept a new reality of China as East Asia’s great power and Southeast Asia as its strategic backyard– no matter the repercussions for China’s image as irredentist and hegemonic. But will China’s latest actions help it earn this acceptance and recognition as a great power, by ASEAN, Japan, South Korea, Australia and the United States, among others? Do Chinese actions inspire confidence in a future where it can play a responsible leadership role, ready to exercise self-restraint and mindful of the sensitivities of both its smaller neighbors and peers? Or will its actions – whether defensive from its perspective or provocative in the eyes of others – lead to outcomes that China itself dreads the most – an offensive remilitarization by Japan and an all-out military containment policy by the United States?

Such outcomes, while conceivably acceptable to at least some in ASEAN, will not redound to Southeast Asia or ASEAN’s benefit and will set back – possibly irrevocably – decades of efforts to build a regional security architecture around the principles of cooperative security and inclusive multilateralism. The higher risk of military confrontation also directly undermines the ASEAN + 3, where cooperation between China and Japan are deemed vital to continued economic dynamism; and the East Asia Summit where the challenges of developing new approaches to provide collective strategic leadership for the East Asian region have yet to be met.

ASEAN itself cannot afford to ignore these new developments and merely focus on its own community building project, even as the 2015 milestone rapidly approaches. The stronger push for regional integration that 2015 symbolizes will not prosper if great power rivalries contribute to division and polarization among the member states of ASEAN.

In the South China Sea, the slow-moving consultations for a legally binding regional code of conduct are bound to become moot if the current status quo should evolve into competition for military control or administrative jurisdictions over wider and wider spaces of oceans or airspace. Middle power diplomacy will slip into even greater irrelevance as the military-industrial machineries step into high gear, and an even greater danger lurks if arms races by great powers trigger higher defense spending by Southeast Asian countries, many of whom are still embroiled in disputes with neighbors. The level of insecurity and gravity of security dilemmas can only increase under such scenarios.

Strategic rivalry among the great powers can only make things more difficult for ASEAN and its member states. What ASEAN can or should do about it seems to be a question that isn’t yet being seriously asked.

Aileen San Pablo-Baviera

Dr. Aileen San Pablo-Baviera teaches at the Asian Center, University of the Philippines

Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia. Issue 15 (March 2014). The South China Sea