The image of Indonesia as an agrarian nation, a modern country whose agricultural roots should not be forgotten, remains popular in Indonesian political discourses. Cliché as it may be, Indonesian politicians embrace this notion – or at least pay a lip service to it (Davidson 2018). The latest general elections held last year also showed how political hopefuls tried to outperform each other in their pro-peasant and pro-rural rhetoric.

Ironically, this is in stark contrast with the realities of local agrarian conditions in post-authoritarian Indonesia. Although peasants and sympathetic activists have more freedom to organize politically and promote their aspirations, they also face the continuing threat of state-backed and business-backed violence and the ravages of market expansion.

This situation suggests the enduring appeal of and concern for agrarian issues in Indonesian politics. Strangely, there is a lack of analysis that is more attentive toward the dynamics of agrarian politics in Indonesia. One can even say that there is a tendency to elevate urban-based political processes as a primary focus of analyzing contemporary Indonesian politics. 1 This approach however overlooks rural areas as an important locus of political contentions in post-authoritarian Indonesia.

This essay therefore takes a different angle by looking at agrarian politics as a lens to examine Indonesia’s post-authoritarian political trajectory. By utilizing the perspective of agrarian political economy, I show that despite its relative institutional stability, Indonesian democracy still struggles to combat illiberal practices by state and oligarchic actors and improve its quality. This tug-of-war between the peasant-activist coalitions and the conservative forces of the state and the capitalist class takes place in local agrarian politics, a hidden major arena of political competition in the democratic period.

Agrarian Political Economy as an Analytical Framework

Recent scholarly debates on post-authoritarian Indonesian politics have discussed the influence of oligarchic actors – whether it is defined as the ultra-rich or the predatory state and business elites – in politics (Robison and Hadiz 2004; Winters 2011) and the possible counter-oligarchic responses from the lower-classes and the activists against them (Caraway and Ford 2014; Mietzner 2014). While the emphasis on the material power of wealth and the organizational power of the subaltern actors in this body of literature is appreciated, we still need a more thorough explanation of how political contestation for state and economic resources in subnational and peripheral areas influences political dynamics and democratic quality in Indonesia.

Here, insights from studies on agrarian political economy can be a better guide to understand the trajectory of Indonesian democracy. Henry Bernstein (2010), a leading agrarian political economist, urges analysts to use class relations in rural areas as a starting point to analyze agrarian transformation and its socio-political impacts. This means paying attention to the structure of domination of rural economic resources and, by extension, political power (Sidel 2014; Usmani 2018). Additionally, one also needs to look at the political impact of commodification of resources (Sidel 2015).

Using these insights as an analytical framework, I now look at four case studies of agrarian politics in post-authoritarian Indonesia, namely 1) agrarian politics during the democratic transition period, 2) agrarian resource conflicts, 3) the contraction and expansion of rural democratic space, and 4) the influence of extractive businesses in electoral competitions. Through these case studies, I show how the institutional stability of Indonesian democracy hides the political domination of state and oligarchic interests at the expense of ordinary citizens, especially in rural areas.

Democratic Transition: A Missed Opportunity

Organized peasants and agrarian activists played an important role in exerting pressure against the decaying New Order authoritarian regime in the 1980s. 2 During the tumultuous transition period (1998-1999), the transitional government implemented a number of policy reforms, including putting an end to the centralization of power by promoting decentralization and creating avenues for leaders of peasant communities, agrarian activists, and critical scholars to convey critiques and suggestions to the government. At the same time, peasant unions and other related agrarian organizations and alliances actively mobilized and pushed the national and local governments to take a more pro-peasant stance in agrarian policies. After a series of mass protests, a key legislative victory was achieved with the passing of the Parliamentary Decree No. IX/2001 (TAP MPR No. IX/2001) that strengthens the mandate to implement land reform (Rachman 2011, 53-65).

But these high hopes soon faded due to the difficulty of implementing pro-peasant policies on the ground in the context of fluctuating political conditions and the overlapping authorities between national and local government. At the same time, the government’s shifting focus on political stabilization and other macroeconomic issues, combined with the continuing dominance of New Order-linked big businesses in plantation and forest resource sectors meant that agrarian justice no longer became a major political agenda. This suggests that democracy was consolidated without disrupting the old elites’ entrenched interests in rural political economy. Democratization was achieved without a transformation toward more egalitarian class relations in rural Indonesia.

Agrarian Resource Conflicts

In post-authoritarian context, rural resource governance soon became a major site of tensions between oligarchic and counter-oligarchic forces, especially with regard to land and forest resources. The authoritarian developmentalism of the New Order fueled its rapid economic growth by the exploitation of land and forest resources at the expense of ordinary rural citizens. State-owned enterprises and state-backed private corporations expanded their big plantations and agricultural businesses without proper consultation with local peasant communities, leading to the rise of land-grabbing cases in the 1970s and 1980s. This led to rising discontent among peasant communities and their activist supporters, which rejuvenated various local coalitions and alliances for land rights and agrarian justice from the late 1980s.

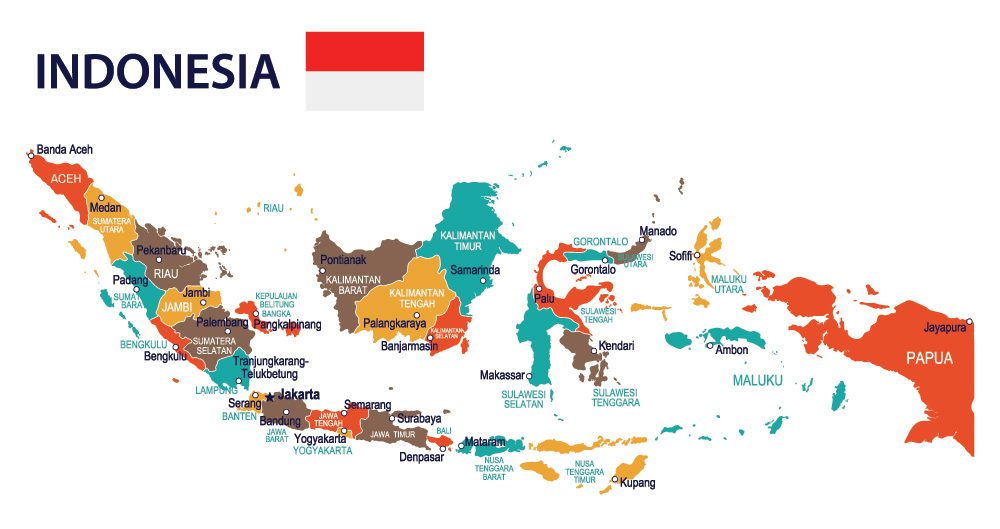

Democratization and decentralization opened up new political opportunities for these local agrarian movements. In early 2000s, local peasant unions sprung up in various places across Indonesia. In my conversations with local peasant leaders and agrarian activists in several provinces, such as Bengkulu, West Java, Central Java, and South Sulawesi, I found that local peasants and activists established these unions as an organizational vehicle to promote the rights of peasants and other rural lower-classes, especially land rights. Many of these unions were formed as a community response toward existing land conflicts in their respective areas.

However, this new wave of agrarian activism has not yet transformed into an effective counterbalance against the mighty rule of the state and capital at the national level. To date, there has been no land reform policy comparable during the height of agrarian populism of the 1960s in terms of its swiftness, redistributive orientation, and socialist-populist undertone. Instead, what the Indonesian government has been promoting since 2005 is a market-oriented land title legalization scheme based on individual ownership. While this policy has been used as settlement mechanisms in conflicts between peasant communities and state and corporate authorities, it does not prevent the transformation of land into commodity – a process that has become a major source of rural contentions in Indonesia in the last few decades. Redistribution of land and forest resources and settlements of land conflicts – two prerequisites for the expansion of civil, political, and socio-economic rights in rural areas for a more substantive democracy – are still a long way to go.

The Contraction and Expansion of Rural Democratic Space

Given the dominance of state and oligarchic actors in rural political economy, it is then unsurprising to see the oscillating contraction and expansion of democratic spaces in rural areas. The continuing interlocking of deep-seated political and financial interests in rural sectors means that rightful criticisms of and oppositions to oligarchic rule in rural areas can be greeted by illiberal, violent responses.

A major indication of this oscillating trend is the rising number of violent agrarian conflicts between state and corporate authorities and peasant communities in post-authoritarian context. Reports from the Consortium for Agrarian Reform (Konsorsium Pembaruan Agraria, KPA), a major land rights NGO in Indonesia, have shown how the rate of land conflicts have accelerated since 2004. 3 For examples, during the ten years of the presidency of Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono (2004-2014), there were more than 1,500 cases of agrarian conflicts covering more than 6.5 million hectares of land involving close to one million rural households (KPA 2014, 12). By the end of the first term of the incumbent president, Joko Widodo (2014-2019), there were more than 1,700 cases of agrarian conflicts and in 2018 alone these conflicts covered more than 800,000 hectares of land (KPA 2019). In these conflicts, state and corporate apparatuses often deploy violent measures against peaceful protests and land occupation campaign by local peasants and activists. Worse, sometimes these protesting peasants and activists are branded as agent provocateurs or communist sympathizers. These repressive measures might be episodic, but they create a climate of fear that limits the willingness of local peasants and civil society actors to speak up.

At the same time, the resistance mounted by local communities and civil society actors against the commodification of rural resources has also expanded the limits of local democratic spaces. 4 Peasant unions and local civil society organizations have made local democracy more vibrant by bringing concerns about land rights and social justice in local political discourses. Some of them even expanded their political advocacy into the electoral arena by establishing alliances with sympathetic politicians or fielding their own candidates in local and national elections. Other opt for the promotion of solidarity economy experiments, by running peasant-owned producers’ cooperatives and credit unions. Albeit limited, these efforts have the potential to expand democratic spaces and limit illiberal and oligarchic influences in local politics.

Subverting Democracy: The Influence of Extractive Businesses in Elections

Another aspect of democratic politics that should examined is the influence of extractive businesses in elections. Sure, Indonesia has passed the litmus test for democratic consolidation and stability by having free and fair competitive elections since 1999. But a deeper look at campaign financing and policy lobbying processes will reveal how extractive businesses influence politics heavily in their favor by financing aspiring political candidates who will in turn issue pro-business policies such as mining licences.

In this quid-pro-quo relationships, extractive businesses, especially coal mining companies, will finance aspiring politicians to participate in the increasingly high cost, money politics-ridden legislative and executive elections. To return their favor, these politicians will then issue mining licences for their business supporters. Studies from the Mining Advocacy Network (Jaringan Advokasi Tambang, JATAM) have shown that the number of mining licences issued in the aftermath of local executive head elections increased exponentially (Jaringan Advokasi Tambang 2018). One study by a consortium of civil society organizations also points out that the number of mining licences issued by the local governments across Indonesia skyrocketed, from 750 in 2001 to more than 10,000 in 2010 (Koalisi Bersihkan Indonesia 2018).

These collusive relationships have brought detrimental impacts to rural communities. It has led to massive socio-ecological destruction of local environment and livelihood. Moreover, it also limits the participatory space for rural communities to express their concerns and aspirations. In this heavily-skewed political arena, money talks louder than the complaints of ordinary villagers and victims of land disputes.

Conclusion

Assessing the trajectory of democracy from the perspective of agrarian political economy shows how Indonesian democracy, despite its institutional stability, still struggles to tame illiberal and oligarchic interests in politics, especially at the local level. In fact, one can even argue that the democratic stability masks the sporadic pattern of local repression and the continuing marginalization of the rural lower-classes. Any analysis of contemporary Indonesian politics, therefore, has to take into account the rural political economy variable.

This persistence of low-quality local democracy stems from local political dynamics shaped by deep socio-economic inequality, especially with regard to access to and ownership of land and forest resources. A more meaningful democracy in Indonesia, where civil and political liberties as well as social and economic rights can be expanded, can only be achieved by addressing this problem.

Iqra Anugrah

Iqra Anugrah is a JSPS Postdoctoral Fellow at the Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Kyoto University

Banner: Papua, Indonesia – March, 2020: Local people developing agricultural practices for sustainable livelihoods in Papua. It’s Unity in Diversity. Photo Bastian AS / Shutterstock.com

Bibliography

Anugrah, Iqra. 2019. “Movements for Land Rights in Democratic Indonesia.” In Activists in Transition: Progressive Politics in Democratic Indonesia, edited by Thushara Dibley and Michele Ford, 79-97. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press.

Bernstein, Henry. 2010. Class Dynamics of Agrarian Change. Halifax: Fernwood Publishing.

Caraway, Teri L., and Michele Ford. 2014. “Labor and Politics under Oligarchy.” In Beyond Oligarchy: Wealth, Power, and Contemporary Indonesian Politics, edited by Michele Ford and Thomas B. Pepinsky, 139-155. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Davidson, Jamie S. 2018. “Rice Imports and Electoral Proximity: The Philippines and Indonesia Compared.” Pacific Affairs 91 (3): 445-470.

Jaringan Advokasi Tambang. 2018. Krisis Rakyat di Tengah Pilkada Serentak 2018. April 10. Accessed March 26, 2020. https://www.jatam.org/2018/04/09/krisis-rakyat-di-tengah-pilkada-serentak-2018/.

Koalisi Bersihkan Indonesia. 2018. Coalruption: Elite Politik dalam Pusaran Bisnis Batu bara. Jakarta: Koalisi Bersihkan Indonesia.

Konsorsium Pembaruan Agraria. 2014. Catatan Akhir Tahun 2014: Membenahi Masalah Agraria-Prioritas Kerja Jokowi-JK Pada 2015. Jakarta: Sekretariat Nasional Konsorsium Pembaruan Agraria.

—. 2019. Catatan Akhir Tahun 2018: Masa Depan Reforma Agraria Melampaui Tahun Politik. Jakarta: Sekretariat Nasional Konsorsium Pembaruan Agraria.

Mietzner, Marcus. 2014. “Oligarchs, Politicians, and Activists: Contesting Party Politics in Post-Suharto Indonesia.” In Beyond Oligachy: Wealth, Power, and Contemporary Indonesian Politics, edited by Michele Ford and Thomas B. Pepinsky, 99-116. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Pepinsky, Thomas B. 2009. Economic Crises and the Breakdown of Authoritarian Regime: Indonesia and Malaysia in Comparative Perspective. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Rachman, Noer F. 2011. “The Resurgence of Land Reform Policy and Agrarian Movements in Indonesia.” PhD Dissertation, Department of Environmental Science, Policy and Management, University of California, Berkeley.

Robison, Richard, and Vedi R. Hadiz. 2004. Reorganising Power in Indonesia: The Politics of Oligarchy in an Age of Markets. London and New York: Routledge.

Sidel, John T. 2014. “Economic Foundations of Subnational Authoritarianism: Insights and Evidence from Qualitative and Quantitative Research.” Democratization 21 (1): 161-184.

Sidel, John T. 2015. “Primitive Accumulation and ‘Progress’ in Southeast Asia: The Diverse Legacies of a Common(s) Tragedy.” TRaNS: Trans –Regional and –National Studies of Southeast Asia 3 (1): 5-23.

Slater, Dan. 2010. Ordering Power: Contentious Politics and Authoritarian Leviathans in Southeast Asia. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Usmani, Adaner. 2018. “Democracy and the Class Struggle.” American Journal of Sociology 124 (3): 664-704.

Winters, Jeffrey A. 2011. Oligarchy. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Notes:

- This is also true for the study of Southeast Asian politics more broadly. For instance, some recent treatments on authoritarian formation and democratization in Southeast Asia focus heavily on urban political contentions and conflicts (Pepinsky 2009; Slater 2010). ↩

- For a fuller analysis on this issue, see Anugrah (2019, 80-82). ↩

- Agrarian conflict reports from KPA are available online in Indonesian at http://kpa.or.id/publikasi/daftar/laporan/ ↩

- Again, I tackled this issue in another published work (Anugrah 2019, 86-90). ↩