The peace process between the Government of the Philippines (GPH) and the National Democratic Front of the Philippines (NDFP) has been going on and off for thirty-two (32) years now, ironically to resolve an armed rebellion that has in turn lasted for fifty (50) years. Six presidents starting from Corazon Aquino in 1986 have engaged in protracted negotiations with communist rebels to secure a lasting peace. Judge Soliman Santos, Jr., who has been a city Judge in Bicol Province and was a former NDF leader, refers to it as “ this protracted peace process almost as long as the protracted people’s war.” But can a durable political settlement really be reached?

This paper argues that a final political settlement is not possible until both parties genuinely and fundamentally agree to end the violence. But what has become clear over time is that both Parties have looked at negotiations as opportunities that allow both sides to secure economic and political benefits, gain some kind of respite from the fighting, be visible in the public consciousness, have a voice in a public conversation that engages a sizeable intellectual audience, and lastly, and interestingly, as a way to actually still wage war, physically and symbolically, from both ends of the negotiating table.

The peace process has turned into a shared narrative rife with tactical discontinuities borne out of a separate understanding and definition of the sort of peace that lies at the end of the process. In this more disjointed narrative, one side seeks peace at the end of a mailed-fist approach, while the other seeks peace through the seizure of state power. In other words, both think that peace is possible only after their victory.

This paper hopes to show and study preliminarily the content, strategies, and tactics that continue to box and freeze the peace process through the years. This will be taken from interviews, mostly of Francisco Lara, Jr., long-time Head of International Alert and one who has had a long reputable experience in conflict resolution, having actively participated in these talks. Another most insightful reference is Judge Soliman Santos,Jr., who through his papers and speeches, continues to monitor and comment on the negotiations. The paper is also informed by others who have been part of the talks at one time or another, and of those who have followed and analyzed said peace talks. It will also look at signed agreements and documents based on two important books released by both parties: The GRP-NDFP Peace Negotiations: Major Written Agreements and Outstanding Issues, published by the National Democratic Front of the Philippines [NDF-Monitoring Committee: Quezon City, Philippines, March 2006] and The GRP-NDF Peace Negotiations, published by the Office of the Presidential Adviser on the Peace Process (OPAPP) and the United Nations Development Programme [Pasig City, Philippines, c2006].

For peace and conflict scholars who have been monitoring the GRP-NDFP peace process, an important nagging puzzle is: why has a final political settlement evaded the Parties in the GRP-NDFP peace process despite more than thirty-two (32) years of formal and back-channel negotiations? And the even more significant paradox is: why have both Parties continued to engage in negotiations despite knowing they will only fail to reach an agreement? Why have the peace negotiations remained impervious to collapse?

If the two parties are serious about resolutely ending violence, then they must also begin to imagine what can, and must, happen next. The paper notes that negotiations have been conducted without clearly agreeing, and perhaps intentionally, how the end of violence between the protagonists will actually look like. Lara says and I quote:

“This obvious flaw is almost a self-inflicted wound that has enabled both Parties to soldier on, so to speak, in negotiation after negotiation, as if operation after operation, of a prolonged and protracted conflict.”

For example, among the many issues that need to be addressed, two fundamental issues avoided or skirted by both Parties, wittingly or unwittingly, are:

- Will the rebels be allowed to maintain their weapons, and

- Will the perpetrators of war crimes and human rights violations from both sides be exempt from punishment and the rendering of justice for the crimes they have committed? These issues fall within the broad framework of transitional justice, and disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration. Demobilization and reintegration have been relegated as a last component of the negotiations under “end of hostilities and disposition of forces,” an agenda item that both Parties have failed to collectively discuss in previous talks. Transitional justice isn’t even in the post-conflict agenda.

Basic issues, along with other critical issues such as extortion or “revolutionary taxation,” or the conduct of a bilateral ceasefire, or the establishment of stationary rebel camps have been consciously avoided, even though they are essential in generating trust and building a public constituency in support of the peace process.

Without a shared understanding of, and an agreement on, what the end game must look like, both Parties are bound to view the peace negotiations as tactical opportunities for securing benefits that otherwise would not be possible if ever armed violence is effectively suspended, and a fragile peace is established.

These benefits include:

- The release of CNN (CPP/NPA/NDF) cadres and combatants in jail, and of soldiers and policemen seized by the NPA;

- The continuation of extortion or revolutionary taxation, and

- The tactical distancing of their ground forces to reduce armed clashes.

For both the GRP and the CNN, the conduct of peace negotiations also allows the continued prosecution of a low-intensity conflict that gives one side, the NDFP, a status of belligerency, and the other side, the AFP/PNP, continued access to increased budgetary outlays. Eduardo Quitoriano, an active consultant in post-development projects funded by Belgian ODA, put it this way:

”The CPP-NPA got breathing space to expand and re-establish its middle bureaucracy (as prisoners were released) but also, they risked exposing its personalities and network. The AFP gained a lot of information and is currently using that to launch its offensives.”

The paper will focus on two important episodes in the history of the GRP–CNN peace negotiations: one, the formal and back-channel peace negotiations under President Benigno Simeon Aquino III, and two, the back-channel and formal talks prior to the termination of negotiations under President Rodrigo Duterte.

A comparative approach is essential to understand how the reasons that prompt the conduct of formal negotiations, in the first place, have endured and persisted despite the limited success of the talks.

Though it provides a quick history of the peace talks from when they began in 1986, the period of analysis is limited to 2010-2018. The contrasting nature and substance of the negotiations under the Aquino and Duterte administrations requires closer scrutiny. There were high hopes for a different kind of peace negotiations under the Duterte presidency, change was coming in a “kind of paradigm shift” as Santos had called it. But in the end, in both cases, both Parties agreed to conduct formal and informal (back-channel) peace negotiations. And in both cases, the back-channel and formal negotiations bore fruit at the outset but later were disrupted by accusations of bad faith and violations of prior agreements thereby terminating the formal negotiations.

It is in fact even superfluous to ask why as this ebb and flow is not endemic to these two episodes alone — the same has happened since the time of President Corazon Aquino. It is as if any attempt to engineer a final political settlement is doomed from the start.

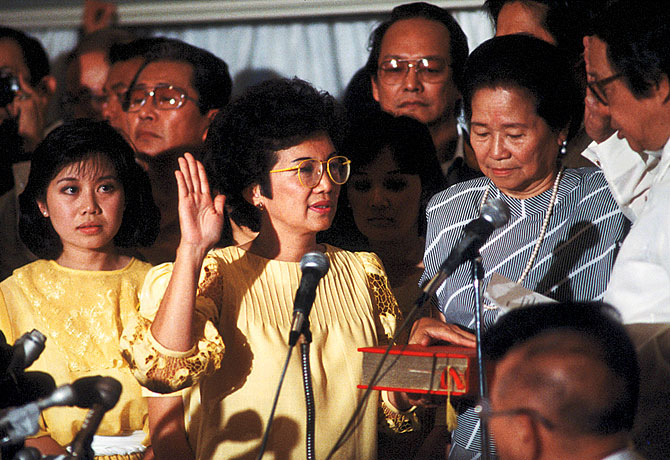

A History of the Peace Talks

Immediately after the EDSA People Power Revolution, Corazon Aquino granted political prisoners headed by Jose Maria Sison executive clemency. As part of her government’s policy of reconciliation, she ordered the opening of peace negotiations with the National Democratic Front (NDF), the Cordillera People’s Liberation Army (CPLA) and the Moro National Liberation Front. In May 1986, exploratory negotiations between the two panels, Government and the NDF, began, focusing on possibly ending all hostilities and providing NDF representatives safety guarantees. The military said this was naïve. A carry over perhaps from the the EDSA People Power euphoria. Or an expression of goodwill from both sides who used to be allies against the Marcos dictatorship.

The government panel was headed by Human Rights Commission Chairman Jose W. Diokno, together with members then Agriculture Secretary Ramon Mitra, and Audit Chairman Teofisto Guingona. Designated NDF negotiators were Antonio Zumel and Satur Ocampo.

While a nationwide ceasefire did happen in 1986, on December 10, Human Rights Day, the talks didn’t progress to substantive issues as both panels expected different things: the government offered socio-economic programs to reduce poverty, generate productive employment, and promote equity and social justice when the NDF wanted to begin with human rights issues, and demanded the creation of a new coalition government and a constituent assembly. Diokno tried a compromise with his program called “Food and Freedom, Jobs and Justice” but when on January 22, 1987, demonstrators largely farmers, who wanted to engage Malacanang, were shot at indiscriminately by riot police, the NDF walked out of the talks. Despite the impasse, the government still rolled out an amnesty package for rebel returnees to reintegrate into the mainstream of society.

Journalist and former Human Rights Commissioner Paulynn Sicam, who was technical staff, consultant and panel member, for 26 years, says:

“The CPP may have been forced to sit down with government and talk peace to be relevant after the EDSA People Power, but from the outset, their negotiators’ hands were tied by Joma Sison who thought they had given too much to government by signing an agreement for a two-month ceasefire and ordered them to find a way out of the talks. The Mendiola Massacre is widely believed to have been staged by the Party to give the NDF panel reason to walk out of the talks.” (No evidence given but widely believed means among journalists at that time.)

Aquino appointed new government peace negotiators under the leadership of Senator Teofisto Guingona who was instructed to dialogue with NDF regional leaders. He designated Roman Catholic bishops as regional negotiators or facilitators.

In 1987, Aquino created the Office of the Peace Commission (OPC) whose main function was to define and adopt a systematic approach and an administrative framework for the government’s peace effort. It was chaired by Health Secretary Alfredo Bengzon. The same Administrative Order also formed the Joint Executive-Legislative Peace Council.

Fidel V. Ramos was as committed to a lasting peace and initiated exploratory talks after his State of the Nation Address in 1992. The Hague Joint declaration was signed by both parties on September 1, 1992, agreeing on four issues: 1. human rights and the international humanitarian law; 2. Social and economic reforms; 3. Political and constitutional reforms; and 4. End of hostilities and disposition of forces. Appointed government negotiators were Congressman Ambassador Howard Dee as Head, and as members: Jose Yap, Department of Justice Secretary Silvestre Bello III, Atty. Rene Sarmiento and Zenaida Pawid, who was a peace advocate for the Cordillera peoples.

The end goal was to reach a negotiated peace settlement that would 1) include agreements on reforms, 2) end the armed rebellion, and 3) bring the struggle to the rule of law and democratic processes.

Three more exploratory meetings in two and a half years followed the Hague meeting and netted four other procedural agreements: 1) The Breukelen ( a small town in Utrecht) Joint Statement, 2) Joint Agreement on Safety and Immunity Guarantees (JASIG), 3) Joint Agreement on the Ground Rules of the Formal Meetings, and 4) Joint Agreement on Reciprocal Working Committees (RWCs).

The conduct of the first round of the negotiation in Brussels, Belgium on June 25,1995 was based on these agreements but the next morning, the government suspended the negotiation because the NDF did not show up at the first substantive session. The new precondition to continued meetings was that captured New People’s Army leader Sotero Llamas, a top ranking NPA commander captured by the Armed Forces of the Philippines in an encounter, be brought to Brussels.

After a year of no talks, it was frenetically followed by 15 rounds of both formal and informal meetings from June 1996 to March 1998, that resulted in five more agreements:

- Additional Implementing Rules Pertaining to Documents of Identification,

- Supplemental Agreement to the Joint Agreement on the Formation, Sequence and Operationalization of the Reciprocal Working Committees (RWCs),

- Comprehensive Agreement on Respect for human Rights and International Humanitarian Law (CARHRIHL),

- Additional Implementing Rules of the Joint Agreement on Safety and Immunity Guarantees (JASIG)re Security of Personnel and Consultation in furtherance of of the Peace Negotiations, and

- Joint Agreement in Support of Socioeconomic Projects of Private Development Organizations and Institutes.

However, again, the NDFP protested that the government by insisting on the Philippine constitution as framework for negotiations violated the Hague Declaration, specifically the provision which stipulates that “the holding of peace negotiations must be in accordance with mutually acceptable principles of national sovereignty, democracy and social justice…” While they did agree on this wording, the government panel claims this doesn’t give the NDFP equal sovereign status, that nowhere in the Hague Joint Declaration does it say this, and that in fact, Congressman Jose Yap opened the meeting at the Hague clearly expressing that the GRP panel recognizes only one Constitution and only one rule of law.

So when in August 1998, Estrada signed the Comprehensive Agreement on Respect for Human Rights and International Humanitarian Law or CARHRIL, the GRP insisted that only the government can prosecute, try and apply sanctions against human rights violations. Just as quickly the NDFP protested in favor of their own judicial system and legal processes. Its NPA captured AFP and PNP officials Obillo, Montealto and Bernal. With the impasse, GRP suspended the Joint Agreement on Safety and Immunity Guarantees, or JASIG, for NDF panel members since peace negotiations were not going on. A humanitarian mission headed by Davao Archbishop Fernando Capalla, in March 1999, went to the Netherlands upon their invitation and negotiated for the release of the abducted military personnel, who were released and thus led to resumption of talks. But then again in May, the NDF terminated the talks because the government violated the national sovereignty principle when it ratified the Visiting Forces Agreement. By June, FVR localized the peace efforts to deal with the insurgency.

Sicam comments on hindsight:

“When FVR was president, the CPP initially did not think the peace process could go forward with a so-called fascist general at the helm of the government. But they were surprised at how open FVR was to dialogue, and even to compromise. The Hague Joint Declaration, although flawed and disadvantageous to the government was signed and became the basis for the talks. Most of the existing agreements were signed during FVR’s term. The NDF certainly gained a lot but they held out for more and so FVR.s term ended without a lasting peace agreement.

In GMA’s term, they would look back to the FVR years with nostalgia. They missed his openness and his self-confidence in dealing with them. Certainly, Ramos wouldn’t be labelled by the military as pro-left. It would never be the same again. Although every new administration initiated peace talks with high hopes, the process would invariably fail on the same issues. In addition, the military that trusted FVR’s judgment was not as confident in the judgement of the succeeding civilian presidents.”

Ambassador Howard Dee, in his Ramon Magsaysay lecture, titled “Why is Peace so Elusive?” in September 2018, referred to the peace negotiations he headed in FVR’s time, and lamented too that FVR’s openness and commitment were squandered. It took a military-general president to abolish the anti-subversion law and immediately create in 1993 a National Unification Council that would develop a comprehensive peace process as part of his presidency’s economic program.

Arroyo, recognizing the urgent need to heal and rebuild after the EDSA People Power 2, reconstituted the GRP panel headed by Silvestre Bello III, Department of Agrarian Reform (DAR) Secretary Hernani Braganza, Rene Sarmiento, Riza Hontiveros Baraquel and Chito Gascon. They first conducted back-channel or informal goodwill talks in Netherlands to pave the way for formal peace negotiations which did take place in April 2001 in Oslo hosted by the Royal Norwegian Government.

Negotiations were at two levels: Panel-level meetings to build up confidence and goodwill between the two parties, and Reciprocal Working Committee meetings on Social and Economic Reforms to discuss and agree on how to conduct negotiations on the draft of what is to be the Comprehensive Agreement on Social and Economic Reforms (CASER). The next round in June was suspended by the government reacting to the NDF panel’s chair congratulating the Fortunato Camus Command for the assassination of then Congressman, ex-martial law torturer, Rodolfo Aguinaldo. The GRP said it violated the expressed commitment of both parties to improve the climate of the peace talks. After some time, the GRP, through back-channel meetings, initiated reviving the talks but the NDF officially rejected it in April 2002 unless the US and EU took the CPP/NPA and Jose Maria Sison from their terrorist list. And despite then Speaker of the House De Venecia’s initiative to reopen the negotiations, the NDF refused arguing that the new proposed Final Peace Agreement was actually a surrender document.

Informal exploratory talks followed in Oslo and succeeded in resuming the formal negotiations after three and a half years of silence. After meetings in February, April and June, they signed the Oslo Joint Statements 1 and 2 where both 1) renewed their commitment to address the root causes of the armed conflict by adopting social, economic and political reforms; 2) agreed to accelerate the work; 3) form the Joint Monitoring Committee, the agreed interim body that will monitor the implementation of the Comprehensive Agreement on Respect for Human Rights and International Humanitarian Law; 4) agreed to continue confidence build-up efforts; and 5) agreed on the date of the next round of talks in August in Oslo. The NDF didn’t honor it however because the CPP/NPA and Sison got relisted by the US as terrorists when in the first meetings in Oslo GRP promised to communicate with the US and demand to respect our sovereignty and desire to resolve the armed conflict, and that the GRP is officially engaging the CPP/NPA represented by Sison.

In February 2005, Arroyo formed a new GRP Panel headed by Nieves Confesor with members Rene Sarmiento, Sedfrey Candelaria, Annabelle Abaya and Paulynn Sicam. This new group began to consult with the different peace constituents such as the military, police, local government units, and civil society groups, updating them on the status of the peace talks and soliciting inputs on various issues.

On August 3, however, the GRP didn’t only cancel the scheduled talks but also suspended the Joint Agreement on Safety and Immunity Guarantees. NDF Panel Chair Luis Jalandoni issued a press statement in July that the Arroyo Government, consumed by a serious election cheating scandal, needed to be replaced by a “transitional governing council.” CPP declared it was going to wait for a new government before resuming peace talks. Roger Rosal, spokesperson for the CPP/NPA, even asked “What is the use of continuing talks with a lame-duck regime that will be gone very soon?”

The Norwegian Facilitators informally talked to both parties and agreed on a resumption but the NDF disowned any agreement to go back to the talking table. The impasse lasted seven years.

Jose Maria Sison, in the book, The GRP-NDFP Peace Negotiations: Major Written Agreements and Outstanding Issues published by the NDFP, cites that in Arroyo’s time, the Joint Secretariat received in 22 months since it opened 544 complaints against the GRP armed forces and 58 against the NDFP armed forces (or the NPA). He believes that people are confident about CARHRIHL, the only real document signed after The Hague Joint Declaration, and believe in it as a mechanism for peace but that the Joint Monitoring Committee has not met on these complaints, therefore “… so many victims of violations of human rights and international humanitarian law are being denied justice.” {P.2}

The Aquino-CNN Peace Talks

International Human Law and human rights lawyer and Judge Soliman Santos, Jr., long-time peace advocate who has monitored the peace talks since his first engagement in it in Naga while working with Jess Robredo in 1986, says that it was clear from the “verbal and body language” of both the GRP and the CNN panels that there was lukewarm interest in furthering the peace negotiations after it was formally reopened in 2011. He thinks both parties have given their own strategies more importance: the GRP’s then more sophisticated Internal Peace and Security Plan (IPSP) Bayanihan or the old Protracted People’s War (PPW) with its new target of strategic stalemate in 5 years (supposed to be 2017). Santos quotes from the CPP’s highest policy statement on its 43rd anniversary on December 26, 2011:

“The Aquino regime has simply shown its lack of sincerity and seriousness in peace negotiations with the CNN. We should dispel any illusion that the regime is interested in addressing the roots of the armed conflict and forging agreements with the CNN on social, economic and political reforms. Clearly it is hell bent on destroying the Party and the revolutionary movement.”

And on the 43rd anniversary of the NPA on March 29,2012, it added:

“The Aquino regime is not interested in serious peace negotiations with the CNN. Within the framework of its Oplan Bayanihan, it considers peace negotiations only as a means to divide and weaken the revolutionary forces while it escalates brutal military campaigns of suppression to decimate the armed revolution and suppress the people’s resistance. Unwittingly, it is inciting the people and the revolutionary forces to intensify their armed resistance and to advance the people’s war from the strategic defensive to the strategic stalemate.”

Santos asked (in 2012) that if the CPP/NPA believed this, then they should have totally and categorically pulled out from peace negotiations. The CPP anniversary statement explains why they have not and will not:

“However, we continue to express our desire for peace negotiations in order to prevent the enemy from claiming falsely that we are not interested in a just and lasting peace and also to keep open the possibility that the enemy regime would be compelled by the crisis and/or by our significant victories in people’s war to seriously seek negotiations. Indeed, the only way to compel the enemy to engage in serious negotiations is to inflict major defeats on it and make it realize the futility of its attempt to destroy the revolutionary movement, especially the people’s army.”

The Aquino administration also focused on the peace negotiations with the MILF as his legacy because they seemed more genuinely committed to resolving the conflict. A general ceasefire was one of its significant agreements when they began talking in 1997, whereas the CNN is always averse to a ceasefire. Because the MILF shifted from armed struggle to peace negotiations toward reaching a Bangsamoro self-determination, it was easier for the GRP to engage them constructively. This engagement was strategic and not just tactical for the MILF. Santos says that clearly for the CNN, the peace negotiations are tactical: for international diplomatic recognition of the status of belligerency and help secure legitimacy internationally in view of their terrorist listing; for propaganda; for prisoner releases. There is no strategic decision to sincerely give peace negotiations a real chance at political settlement. The CPP mocked the MILF for allowing the Aquino regime to use the peace talks to hoodwink them. Lara recalls that in the early exploratory talks after Aquino took office, it was even being considered that maybe the guerrillas could take on other tasks like being forest rangers when they reintegrate, or that President Aquino, P-Noy and Jose Maria Sison, Joma, could perhaps meet, face to face.

By late December of 2014, after Pope Francis’ visit that literally took the country by storm, there were feelers that CNN wanted to resume talks. Trillanes then asked was there time for it and what could be achieved, if at all, in a year and a half? But surprisingly, both panels actually agreed there was enough time to at least draft a Comprehensive Agreement on Social and Economic Reforms and a Truce and Cooperation Agreement based on a general declaration of mutual intent. Some observed that this initiative from the CNN came after the country-based CPP leaders, couple Wilma and Benito Tiamzon, were captured. Without the couple believed to be hardliners, Joma seemed to have acquired more elbow room in the negotiation. The tone of his statements changed from that of the earlier anniversary statements. But as Lara said, the GRP was under siege after the major tactical errors that led to the deaths of 44 SAF commandos, which in turn threatened the passage of the Bangsamoro Basic Law. And it was ironic that the government dropped negotiations with CNN in favor of the BBL but by the end of Aquino’s term, neither the BBL nor the CNN peace process moved forward.

The Aquino government did succeed in securing the Comprehensive Agreement on the Bangsamoro but it didn’t amount to much because the enabling law to institutionalize it was not passed. The passage of a renamed Bangsamoro Organic Law would only happen under the Duterte presidency.

The Duterte-CNN Peace Process

In 2016, the campaign news reported that presidential candidate Davao City mayor Rodrigo Duterte had asked his former Lyceum Professor and CPP founder and Chair Jose Maria Sison to once and for all abandon the armed struggle and instead, join the democratic process, use it to fight for the kind of change, for substantive economic, social and political reforms, the communists have been fighting for for almost half a century. He was said to have admonished Sison:

“Armed struggle as a means to achieve change is passe in the modern world we are living in today. Over 40 years of armed struggle and thousands of lives lost is too much to bear.” He was direct and he cut through the charade. He was asking the CPP-NPA-NDFP to change its strategy of a protracted people’s war to bring about the change from a “semi-colonial and semi-feudal” system to a “national democratic” one. He was asking them to stop using the peace negotiations as another stage of struggle subsumed under the PPW.

Santos saw this challenge as a paradigm shift in the most recent peace negotiations. He asks:

“Is it not a viable alternative for the revolutionary movement to strategically and transformationally ‘join (and reform) the democratic process instead based on the movement’s faith in the masses and in the merits of the national democratic program? Are the masses who make history not bound to sooner or later support that program which presumably represents their best interests if that program and its standard bearers are offered as a choice in a viable democratic political process that does not involve a costly resort to arms?”

Lara says he believes to this day that Duterte genuinely thought he could reach a political settlement with the CNN because he had been dealing with them since his time as mayor of Davao City.

“Everyone acknowledges Duterte’s successful record when it comes to brokering bargains with various groups that had a short-term or long-term presence in the city, whether it’s the MNLF, the MILF, or the CNN, including warlord clans such as the Ampatuans during the height of the latter’s power. In turn, these groups respected Duterte and avoided creating tensions, or starting wars within the city. He is not anti-communist, nor discriminatory to Muslims and the indigenous peoples.”

In response, Sison, in the same Davao media forum, was supposed to have referred to “an impending interim ceasefire.” He went on to say:

“The ceasefire between the armed forces of the GRP and the CNN, and the eventual conclusive success of the peace negotiations should make more resources available for expanding industrial and agricultural production and education, health and other social services. The people’s army will not be idle even if it is in a mode of self-defense and does not actively carry out offensive military campaigns and operations against the AFP and PNP. It can continue to engage in mass work, land reform, production, health care, cultural work, politico-military training, defense and protection of the environment and natural resources against illegal mining, logging and land grabbing, and it can continue to suppress drug dealing, cattle rustling, robbery, kidnapping and other criminal acts as well as despotic acts of local tyrants.”

For the first time, too, the CNN called the GRP the Duterte Regime, not the usual US-Arroyo or US-Aquino Regimes. That was a good sign. It was off to a good start.

On June14-15, 2016 presumptive President Duterte initiated exploratory talks in Oslo, facilitated by the Royal Norwegian Government. The GPH was represented by then incoming Presidential Adviser

On the Peace Process Secretary Jesus Dureza and incoming Panel Chair Silvestre Bello and Panel Member Hernani Braganza. Braganza brought in Lara as Consultant and Technical Staff. This resulted in the signing of a Joint Statement on June 15, 2016 which set the agenda for the resumption of the talks.

I asked Lara how he was perceived in those talks considering he is an ex-Party member and now represented the government. Lara was in the CPP for more than 15 years and worked with peasants before he moved to NGO work and even government work with Horacio Morales when he was Estrada’s Secretary of Agrarian Reform.

“The relationship blows hot and cold—with the temperature shifting quickly and easily depending on my acquiescence or contestation of their analysis of the situation and the effectiveness of the political strategies that they employed.”

He shares that when he was part of a 4-person exploratory team under the Aquino presidency that conducted back-channel talks with the NDFP panel in Utrecht, and continued up to when talks officially resumed starting in June 2016, the relationship was in his own words “robust and friendly, and it allowed him to have honest discussions and feisty debates with the NDFP about the declining prospects of a protracted war that was weighing down on society as a whole. I think I was perceived at this point as a friend and ally who understood the context behind the continuing revolution, and could transmit such context and its concomitant demands to the other side. And perhaps could help flesh out future options for the many senior members of the CNN still involved in the armed struggle.”

I asked him about the unfortunate incident of his being singled out and announced to the press as an opportunist benefitting from huge fees from a London-based NGO, International Alert.

“I was publicly denounced at some point in an NDFP statement as a misleading and opportunist chronicler and analyst of events they did not agree with. This was after I said in a public discussion of the war in Marawi that it was unlikely that the CNN can get involved in fighting violent extremists in Lanao because they were geographically far away. They denounced me because I had unconsciously embarrassed them, and undermined their narrative and imagery of the CNN as an armed movement that was nationwide in scope and network.

When I confronted them after that public statement that their claims were ‘fake news,’ their lame response was that this was just their ‘carino brutal.’

That to me showed their ugly side: the kind of relationship the CNN wanted to have with many former comrades – often transactional and opportunistic, with no care about the impact on the person they deal with.”

I asked him to describe the room atmosphere during these talks.

“There would be a lot of tension, a lot of bad and painful words, cursing at times, but never against each other. There were always cooler heads in these negotiations that could pull parties away from the brink. When there were walk-outs, they were usually meticulously planned by either side, and in fact formed part of a strategy, rather than spontaneous outbursts. By this time, we would have been negotiating for so long, and more or less knew how each side would react. A lot of language engineering is done by both sides to prevent offending the other.”

The official Update Report on the GRP-CNN Peace Negotiations dated July 12, 2018 states the following as the Major Gains:

President Duterte has undertaken unprecedented and even unconventional actions and decisions to seek peace.

- Engaged the CNN even before his assumption into Office through back-channel talks conducted by incoming peace officials. This broke the impasse in the peace talks (2011-2016).

- Personally welcomed and met with the top leaders of the CNN in Malacanang

- Released prisoners facing criminal charges to allow them to participate in talks to be conducted abroad and in the Philippines

- Declared a unilateral ceasefire, which was reciprocated by the CNN, and this lasted for 6 months from August 2016-January 2017. This literally reduced violent incidents on the ground.

- The four rounds of talks (August, October 2016, January, April 2017) achieved the following:

-

- accelerated and simultaneous dicussions on drafts of agreements on the remaining three substantive agenda of the talks: socioeconomic reforms, political and constitutional reforms, and on end of hostilities and disposition of forces, based on agreed common outlines;

- completed common draft chapters on Agrarian Reform and Rural Development (ARRD) and on National Industrialization and Economic Development (NIED) of the Comprehensive Agreement on Social and Economic Reforms initialed by the GRP-CNN bilateral teams in November 2017;

- got the following documents signed by both Parties: i. Supplemental Guidelines for Operationalizing the Joint Monitoring Committee under CARHRIL, ii. Ground Rules for the conduct of meetings of the Reciporcal Working Committees for Social and Economic Reforms, and iii. Interim Joint Ceasefire Agreement to become effective upon signing of its implementing rules.

Report says that despite the positive developments, the peace talks were disrupted four times in 2017 due to the CNN’s withdrawal of the unilateral ceasefire and continuing intensification of NPA attacks against government forces and civilians. The GRP had to cancel the following: a) in February the Formal talks and the Joint Agreement on Safety and Immunity Guarantees (JASIG); b) in May the Fifth Round of Formal Talks; c)in July the Back-channel Talks; and d)in November also the Back-channel Talks.

Finally, because the CNN failed to show sincerity and commitment to pursuing genuine and meaningful peace negotiations, Duterte signed Proclamation 360 on November 23, 2017, terminating the peace negotiations and instructing the OPPAP/GRP to cancel the scheduled peace talks and meetings with the CNN. Shortly after, he signed Proclamation 374, declaring the CPP-NPA a terrorist organization, and the Department of Justice filed last February a petition in court under the provisions of the Human Security Act for a judicial affirmation.

But on April 4, Dureza issued a statement that President Duterte, in a Cabinet meeting, directed him to work on the resumption of peace talks with the CNN, emphasizing the importance of forging a ceasefire agreement to stop mutual attacks and fighting while talks are ongoing. According to Dureza, the President said:” Let’s give this another last chance. He even committed to provide support, if necessary, to replace the revolutionary tax that he wants stopped.

On June 14, PAPP held a press conference where they announced that even back-channel meetings would be delayed because the president wanted the bigger peace table engaged, meaning, the general public as well as other sectors in government. This was to make sure all those consensus points and agreements forged in the negotiations table really have palpable support from them. The CNN were invited to attend the public consultations on these peace negotiations.

So where at is this major effort now? On July 5, the PAPP released a statement that, following the command conference convened by the President the night before in Malacanang, peace talks with the CNN are still open subject to the President’s four premises: 1) there will be no coalition government, 2)the so-called collection of a revolutionary tax will be stopped, 3) the venue of the talks will be local, and 4) there will be a ceasefire agreement that will encamp in designated areas armed NPA members.

The president is also encouraging local government units to agree on local peace arrangements with insurgents in their respective areas. He also keeps open the possible resumption of talks to be still facilitated by Norway. And on July 11, he convened the cabinet cluster on Security, Justice and Peace to discuss localized peace engagement with local communist groups. The guiding framework for this will be covered in an Executive Order.

Waging Peace Outside of the Negotiation Table

The story of our long-running peace negotiations has been one of “talking while fighting,” and when it got worse, “fighting without talking.” The peace process under the Duterte presidency which for all intents and purposes was off to a good start, went quickly from most promising to “talking without fighting” to “fighting without talking” and finally, to the government’s all-out war, all in a matter of just six months.

Santos agrees that it is about time to once and for all pursue this localization of peace engagement with insurgents. Every failed formal negotiation so far in our national narrative always ended with the suggestion that it be brought to the local government units but never seriously and officially initiated. It almost always sounded as a threat to the CNN who definitely didn’t like the idea of dispersing the power. But even if the big peace talks were to continue, the new paradigm shift should be that it adopt the community-based approach, which entails consulting the various sectors of the general public. And it should be seen as central and not just supportive of the panel-to-panel negotiations. Santos saw this work in Naga in 1986 with Robredo’s efforts to dialogue with the poor and discontented. This worked in the Bondoc Peninsula in Quezon Province, considered a hotbed of insurgency as it is one of the poorest areas in the Philippines.

If we want a public to own the process of peacemaking, and have a stake in it, then it is best done at the community level. As has been observed over the years, the formal national-level GRP-CNN peace negotiations held in Europe are so top-level and detached from what actually happens on the ground. There is a huge gap between the top and the bottom, and therefore these negotiations don’t stand on a solid stable foundation. Even local communities in conflict-afflicted areas are far removed from these talks when the local issues should naturally link up to the national issues. These issues are not isolated cases.

In the final analysis, Santos says: “A critical mass of local community-based peace constituencies—in other words, a local mass base for peace—should also be able to help push the talks to move, along with other favorable national and international factors.”

It is the time to seriously initiate and pursue peace engagements outside of the formal panel to panel, or the GRP-CNN, peace negotiations. That these talks have not put an end to the world’s longest-running Communist insurgency, far from it in fact, is a clarion call to all concerned to explore another way of holding these peace talk negotiations.

Maria Karina Africa Bolasco

Ateneo De Manila University Press