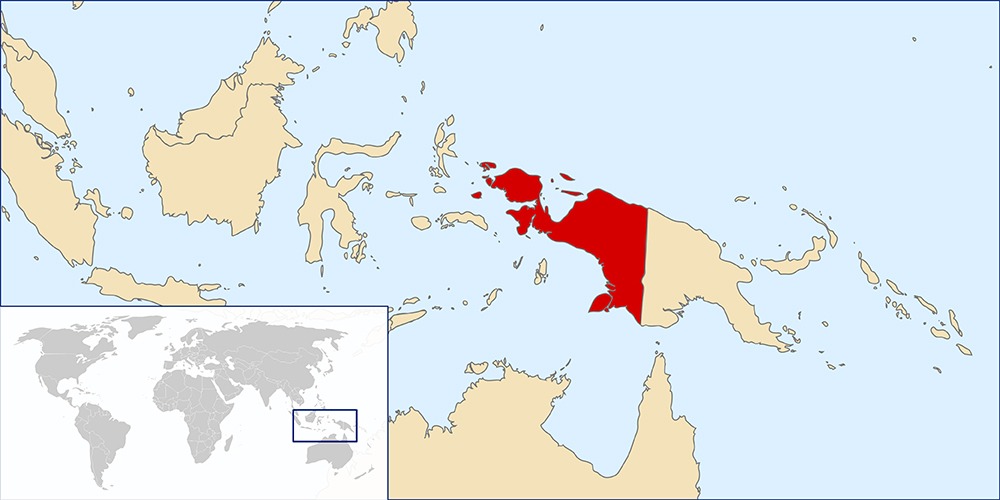

Violence continues in Papua—and its regions. Papua is 421,981 KM2 (3.5 times bigger than Java), with its topography covering mountainous areas and most of the land swamps in coastal areas. When we mention the word Papua, it is almost a definite imagery of a land filled with dense forests, Puncak Jayawijaya, and Freeport gold mine. Does this romantic view still exist today for the most part?

In 2019-2020 in two provinces, the Papua and West Papua provinces of Indonesia, there were a series of incidents that prolonged the weathered conflicts between the Government of Indonesia and Papuans.

Meanwhile, adding to the already tense situation, the central government seemed to be unhinged with the establishment of Kogabwilhan (Komando Gabungan Wilayah Pertahanan/ Joint Command of Defense Zone) and the increase in the status of 23 Korem (Resort Military Command HQ) from type B to type A in several regions, as stated in a Presidential Decree 27/2019 signed by the President on 11 September 2019. This decision, according to analysts, has contributed to violence against civilian non-combatants. This situation occurred primarily by the impacts of security response to actions of those claimed as “OPM (Organisasi Papua Merdeka) combatants.” The military presence in Papua has always been stated to maintain the nation’s unity, security, and stability primarily. In retrospect, analysts have advised that security apparatuses should only be deployed in areas where OPM concentrates, in order to avoid a more significant number of civilian casualties as collateral damage.

Why is it essential to put perspectives to mitigate conflict from the community affected by violence? There have been no instruments available to look upon realities that could reveal the victims’ voices from the ground. Nonetheless, their narratives are essential if policymakers want to move beyond rhetorical statements.

This essay tries to delve into the foundational aspects of violence events in Papua, that risks the well-being of the civilians as collateral damage. From many reports we understand that violence still dominates the Papuan narrative. To go beyond such narrative, we would like to emphasise the needs to attend to the community’s narrative so that decision-makers can find appropriate and non-elitist solutions.

Voices from Below

A “bottom-up” approach that records locality to build peace is not a new milestone in an Indonesia that has a long history of ethnic and religious conflicts. At the end of the New Order in 1998, activists and academics took up the voices from below into peace-building narratives.

Women were acknowledged as important actors because their voices and agency could overcome the patriarchal culture. 1 Indeed, several studies show that the role of local female actors is crucial for the post-conflict recovery period.

The roles of local actors and their structural barriers were also evident in other study of conflict management in Ambon, Poso and Papua. 2 Meanwhile, a thorough mapping of the four roots of conflicts, a variety of local actors, their positions, interests were recorded in the Papua Road Map (2008, 2019). 3 It shows the role of local agencies, namely Papuans and non-Papuans who works hand in hand to produce a “Papua Peace Indicator” as material for dialogue.

In essence, for cases of conflict resolution and peace-building in Indonesia: everyday peace is not a FOREIGN subject. Advocates of peace-building from Indonesia learn very much from other processes, interpret them, and develop strategies as part of their decision-making materials. This is where the gap becomes apparent later. It is the gap between the dimensions of the power relay among decision-makers and the urgency of solving problems presented through a bottom-up approach based on locality.

Roger Mac Ginty (2014) reviews the ideas and practices of everyday peace or the methods by which ordinary individuals and groups seek their survival in the very society ravaged by conflict. 4 His focus is on a bottom-up peace strategy for survival by putting everyday peace into the broader study of peace and conflict. He compiles a typology of the different social practices that make up everyday peace. He asserts that an enhanced form of “everyday peace” (everyday diplomacy) has the potential to go beyond steps to calm conflict to include more positive actions related to conflict transformation.

To contextualise Mac Ginty’s reading in the Papua case, it is important to include more narratives, especially on the persistence of local actors’ efforts. In addition, it will not focus only on elite actors in their efforts to achieve long-term peace. Hence, the public will understand the discourse on “locality” and “agency”, even amid acute social fragmentation.

Locality of Peace Resolution based on Papua Local Contexts

We argue that the current government must change its perspective on the security approach. The government’s approach aims solely at stemming the armed separatist movement because it has an impact on reducing the sense of security in society.

If the community continues to feel insecure for fear of being arrested or becoming “collateral damage” because it is trapped in a conflict situation, any development and welfare approaches from the government will be useless. The government’s credibility in the prevention (cycle) of violence is also damaged.

Most of the Papuans have become too familiar with violence and conflicts over the last 50 years. However, any tension or dispute could usually be solved under traditional processes, some known as the ceremony of “bakar batu” or “tikar adat”, and so on. Principally, the Papuans have recognised some principles of democracy, such as equality and participation in the decision making process. These local values are important in dealing with internal conflict resolution.

With regards to human rights violations/abuses in Papua, it seems that the local mechanism has not yet been considered as tool of analysis. The political process seems to have no reason to appraise it. Legal aspects, including the investigative process, are mostly based on formal and legalistic approach without further consideration to what the Papuans have experienced as victims, in particular women and children. They do not understand the political games which are taking place within their customary land.

The Papuans become victims not only from the ongoing conflicts but also from being the unbeneficial party. Violence and injustice make is a dark cloud over their future in the land of the birds of paradise.

Another formal approach to Papua is the special autonomy law or Otonomi Khusus (Otsus) since 2001. The law has two intentions. The first is to act as a development platform, and the second is to be a mechanism of conflict resolution. At the beginning, the implementation of Otsus seemed to be a comprehensive approach, especially in developing better education and health for the Papuans, as well as the economy and infrastructure (connectivity).

However, current debate on Otsus has becomes a little muddled. It is because both of those who reject Otsus and those who agree with its continuity do not have method of clear assessment, evaluation and indication about its successes and failures. More critically, there is no new design of the future of Papua with or without Otsus. Thus, it needs to be comprehensively evaluated, in terms of regulation and implementation.

Under this complex situation, the humanitarian approach seems to be very limited in Papua. Ordinary people are trying to share realities on the ground based on their experience, but at the same time decision makers and state planners have failed to do the best for Papua.

The government must develop strategies that can positively change Papua’s social economy and political lives. For example, the people in the conflict areas in Nduga and Intan Jaya districts have been terribly affected with the poor distribution of public services, in particular education and health services.

In regards to the issue of human rights, the most adequate approach is to build understanding about the source of violence and about the complete spectrum of human rights aspects. Not all native Papuans have been treated equally and fairly. Hence, there is a strong need to implement the promotion, protection and fulfillment of human rights principles, in the context of civil and political rights, social economy and cultural rights.

A Way Ahead

The dialogue approach is a strategy of building communication or overcoming the communication impasse due to trust issues between the central government and the Papuans. It is a necessary step to build a joint mechanism to reach an agreement and to formulate joint solutions, especially to overcome unresolved problems in various fields.

In terms of human rights issues, legal processes must be transparent and as part of trust building process. For the long term, human rights resolution should be the main approach to reach solution(s), and also to assist the local community to develop their own potentials and capacities.

We would like to see the shift of national regulation or state policy on Papua that is based on the real conditions on the ground.

Irine H Gayatri & Adriana Elisabeth

Irine H Gayatri is a PhD Candidate at the Gender, Peace and Security Centre Monash University (Monash GPS Centre), Australia. Dr. Adriana Elisabeth is the Coordinator of Papua Peace Network/PPN and Lecturer at the Universitas Pelita Harapan, Indonesia.

Notes:

- https://reliefweb.int/report/indonesia/women-indonesian-peace-table-enhancing-contributions-women-conflict-resolution accessed March 21, 2021 ↩

- See also https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/131092/Conflict%20Management%20in%20Indonesia.pdf accessed March 21. 2021. ↩

- http://lipi.go.id/risetunggulan/single/buku-road-map-papua/16 accessed 21 March 2021 ↩

- Roger Mac Ginty. (2014). Everyday peace: Bottom-up and local agency in conflict-affected societies. Security Dialogue, 45(6), 548–564. https://doi.org/10.1177/0967010614550899 accessed 21 March 2021 ↩