As far as I can tell, there had never been a writer’s conference of this magnitude in the Philippines before December 1958, when I was just about to turn five years old – and there has surely never been one since. And what could have brought all these literary luminaries together to the mountaintop? Nothing less than the same general subject that brings us here together today, in another Asian city, nearly six decades later: the vital, inescapable, and compelling but also troubled, thorny, and challenging relationship between literature and politics.

In that 1958 meeting, the subject fell under the rubric of the conference theme, “The Filipino Writer and National Growth.” In the course of dusting my office library during an idle moment a few weeks ago, I chanced upon the conference proceedings, compiled in a special issue (First Quarter, 1959) of the journal Comment – and it struck me, preparing for this conference with quite another beginning in mind, that it might as well have been 1958 all over again, given what I was dealing with. More than half a century after bringing the best of our literary minds to bear on literature and politics (not to mention two and a half millennia after Plato), we Filipino writers remain consumed by the subject, for good reasons both old and new.

Novelists and Pamphleteers

Typical of the views expressed during that 1958 conference was that of the novelist Edilberto Tiempo:

A novelist and a pamphleteer belong to two different, irreconcilable categories. Literature, we must recognize, is not so directly concerned with finding answers to social problems that will be immediately embodied in action; and, furthermore, novelists and poets are not equipped to substitute for political or economic leaders. Their concern is not so much to act as recorders of life and events [but to] give them synthesis, to give them order and coherence…. The successful writer transcends the incidents of his time and becomes a sage and prophet…. Artistic revelation is his final responsibility to himself and his art.

That sounds today like a fairly safe and sensible statement to make, but in 1958 it was merely the latest in a decades-old series of salvos and counter-salvos fired even before the Second World War by partisans of what, on the one hand, was called the “art for art’s sake” school of poet Jose Garcia Villa and, on the other, the “proletarian literature” bannered by Salvador P. Lopez. In the 1930s, Filipino writers had been torn by these adversarial positions, with Villa and Co. on the cutting edge of poetic modernism and Lopez and Co. harking back to a long tradition of revolutionary and subversive literature in the Philippines.

The critic Elmer Ordoñez, who was one of the editors of that Comment issue, would recall the sarcasm of one of Villa’s staunchest allies, the physician and short story writer Arturo B. Rotor, who had earlier written thus:

That no Filipino has shown a notable grasp of the events that now absorb the country’s attention indicates the extent to which he has failed in his art. No notable story, for example, has appeared thus far about the peasants in Central Luzon and their efforts to improve their living conditions. While the rest of the country are talking about the slums of Tondo, our poets still sing ecstatically about the sunset in Manila Bay. What then shall we think of these writers who debate so learnedly about rhythm and balance in prose and who do not even glance at the newspapers? What shall we say of them who will work for weeks over a single phrase, but who will not spend five minutes trying to understand what is social justice and why some peasants in Bulacan were caught stealing firewood from a rich landowner’s preserves?

Dr. Rotor, who died in 1988, was absent from the Baguio conference so we cannot know for sure what he would have said to the likes of Dr. Tiempo (who, incidentally, neither believed in art for art’s sake, thinking that it lacked “high seriousness”), but we can guess. Indeed, if he were still alive today, he could be making the same caustic complaint about much of contemporary Philippine literature, especially in English – unless he were made to understand, as I shall try to do in this paper, that our appreciation of issues like social justice has become rather more complex than dealing simply with land ownership or gainful employment. These continue to be major problems, for sure, but they have been compounded by such recent developments as the large-scale export of Filipino labor and its effects on the Filipino family, the globalization of economic and cultural modes and practices, and the growth of the digital divide within our societies.

How far have we Filipinos come in our experience of and thinking about literature and politics since 1958?

I’d like to review and examine the impact, if any, of literature on our current political life – my provisional thesis being that while the influence of traditional literary forms has been tremendously diminished by economic and cultural factors, non-traditional forms have taken up the slack, and that the expressive literary imagination continues to be a significant political force in Philippine society today.

Politics and literature have had a long and uneasy relationship in the Philippines, where creative writers and journalists have been the bane of an almost unbroken succession of colonial rulers, despots, autocrats, and dictators. The country’s tortuous political history has given rise to many opportunities for direct engagement in political resistance by Filipino authors, from Francisco Balagtas’s anti-despotic Florante at Laura and Jose Rizal’s novels in the 1800s to the anti-imperialist playwrights of the early 1900s and the anti-Marcos propagandists of the 1980s onwards. Beneath the larger and more obvious national political issues, of course, have lurked the politics of gender, religion, region, and – most importantly in our experience – of class.

But before anything else, a bit of history might be more helpful in laying the groundwork for my thesis.

An Archipelago of Tongues

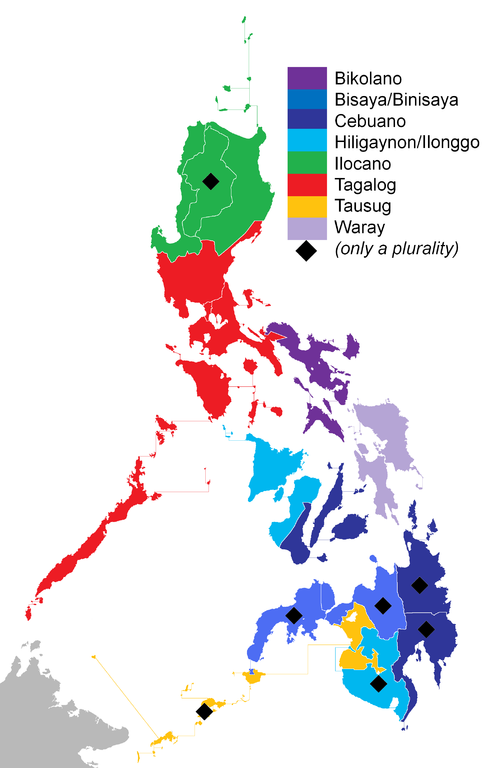

The Philippines today is a country of about 82 million people, mostly Roman Catholic with a small but significant Muslim minority, living in an archipelago of more than 7,000 islands. We were invaded by Spain in 1521, by the Americans in 1898, and by the Japanese in 1941, before achieving independence in 1946. Our racial stock is composed mainly of Malay, Chinese, and Spanish blood, and there has been tremendous intermixing between these races; many indigenous tribes also remain.

Between 1972 and 1986, we were ruled by the martial-law dictator Ferdinand Marcos. We have had three democratically elected presidents since Marcos was deposed in 1986, but we continue to have serious economic and political problems. Our rich are very rich, our poor are very poor, and our poor are very many. One out of every ten Filipinos is living and working abroad. Three out of every ten sailors in the world are Filipinos. According to the Asian Journal Online, there are supposed to be up to 500,000 Filipinos here in Malaysia, about 200,000 of them undocumented.

We have over 100 languages, although English and Filipino are used most widely throughout the nation. Spanish is now used by only a very few – usually the very old, and the very rich.

Our literature represents all these conditions. We had a rich literature in the native languages before the Spaniards came. While there were no great bonfires of heathen books of the kind that happened in Mexico, the friars nevertheless succeeded in over-writing local epics with Christian and imperial themes. And then we learned to write in Spanish, and used Spanish against the colonizer. Our most famous novels, written by our national hero Jose Rizal, are in Spanish, and they helped ignite the revolution against Spain; Rizal himself was executed.

When the Americans came, we took to English like ducks to water. English quickly became the language of the elite, and for the Filipino writer, acceptance into the ranks of American literature became the ultimate goal. Poetry and fiction followed the styles and themes of their American counterparts. Filipino, the other national language, was seen to be a pedestrian language, unworthy of high literary achievement.

A resurgence of nationalism from the 1960s onwards, especially during the martial law years, changed much of that. Writing in Filipino became a form of resistance, and in both English and Filipino, political themes prevailed.

Today, the most palpable element of Philippine social reality is the economic diaspora of millions of our countrymen because of difficult conditions at home, accompanied by the incursion of globalization and its positive and negative effects, and this, too, is reflected in our literature.

A Poetry of Suffering

What is interesting for us today is how closely our political and poetic histories have often coincided. Our heroes were poets, and our poets were heroes. Our first great poet, Francisco Balagtas, published a long poem in 1830 titled Florante at Laura (Florante and Laura), a political allegory against despotism set in Albania, where a Christian prince condemned to death by a usurper is saved by a Muslim warrior.

The revolution against Spain in 1896 was instigated by men of letters, from privileged scholars such as Jose Rizal – who wrote a long lyrical poem, “My Last Farewell,” in his prison cell shortly before his execution, among many other works – to proletarian revolutionary Andres Bonifacio, who wrote a stirring poem about love for the Motherland. These poems continue to be recited and studied in schools.

During the American occupation, political theater – also conducted in verse and song – became the primary form of resistance. And while our literature in English has been largely personal and introspective, the period of political ferment in the 1960s and 1970s saw traditional poets in English exchanging T.S. Eliot for the kind of poetry associated with Ho Chi Minh and Mao Tse Tung. One of our finest poets, Eman Lacaba, joined the communist guerrillas and was killed in combat in 1976; another English major and poet, Jose Ma. Sison, reorganized the Communist Party and continues to lead it in exile from the Netherlands. In 1983, several Filipino poets were fired from their government jobs for publishing a volume of poetry critical of Marcos.

For my generation of young writers in the 1970s, the poet Eman Lacaba was the apotheosis of the writer as revolutionary – an ideal to which we passionately subscribed, seeing ourselves as the vanguard of what we called the Second Propaganda Movement after that of Jose Rizal and his comrades-in-exile in Barcelona in the 1880s. As his older brother Jose (himself one of our most talented and significant poets) recalls, Eman was a prototypical ‘60s hippie enamored of Rimbaud, marijuana, and other mindbenders. “His early poems were high complex, allusive, hermetic, obscure; we had, after all, nurtured our verse on objective correlatives and the seven levels of ambiguity. In the English and Tagalog poems that Eman wrote in Mindanao [where he had joined the New People’s Army], you can feel the tension created by his attempt to turn his back on his former style, and work for greater simplicity, directness, and clarity,” Jose Lacaba notes. Perhaps more than his poetry, Eman Lacaba’s brutal death – shot through the mouth by an informer, after capture in the mountains – ensconced him in the pantheon of Filipino writer-heroes.

That’s a revered status to which the self-exiled chief of the Communist Party, Jose Ma. Sison, probably aspires, having been a poet himself and a SEAWRITE awardee, although it doesn’t help that he remains alive and relatively well in Western Europe. But whatever might be said of Sison’s personal choices and aesthetics, it can’t be denied that his 1968 poem, “The Guerrilla Is Like a Poet,” exerted a profound influence among young writers of that generation, by simultaneously elevating subversion to a fine art and giving poetry, in turn, that edge of lethal danger that decades of submission to formalism had bled from it, as this excerpt shows:

[quote]The guerrilla is like a poet

Keen to the rustle of leaves

The break of twigs

The ripples of the river

The smell of fire

And the ashes of departure

The guerrilla is like a poet

He has merged with the trees

The bushes and the rocks

Ambiguous but precise

Well-versed in the laws of motion

And master of myriad images… [/quote]

Today, with the decline of Marxist regimes and the fall of Marcos, Philippine poetry continues to keenly political, but with a more personal element. We write about the loneliness and hardship of the Filipino worker and migrant abroad, about our love-hate relationship with America, about sexuality and gender, about marginalized communities, about holding on to one’s identity in an increasingly homogenized universe.

These are all the same subjects most of us write about, but what seems particular to the Filipino is our Roman Catholic notion of suffering and sacrifice as prerequisites to salvation. In a sense, our heroes are those who can bear their crosses and endure – indeed, invite – terrible pain. The crucified Christ and the mater dolorosa are iconic figures in our literature and art.

We have a poem which, translated, reads:

[quote]When one submits himself

to wounding,

the sharpest pain is bearable;

when one is unwilling,

even the merest scratch

can fester. [/quote]

What’s interesting is that this poem (quoted by the critic E. San Juan Jr.) was written before the Spaniards came, indicating a certain native propensity for, or at least an awareness of, willingness in encountering pain.

Leon Ma. Guerrero, Rizal’s translator, observed in the context of our Roman Catholicism that “Filipinos do not value failure, or for that matter tragedy, for its own sake, but only insofar as these are submerged into the larger end of sacrifice.” He notes that “We save our highest homage and deepest love for the Christ-like victims whose mission is to consummate by their tragic ‘failure’ the redemption of our nation.” Jose Rizal, Andres Bonifacio, and more recently Ninoy Aquino are three such Christ-figures, after whose deaths the nation came together and overthrew its oppressor.

Our literature and poetry then are an articulation of suffering for freedom and salvation, in both a collective and personal sense. Indeed the writing of the poem itself is already a liberative act that mitigates, even as it celebrates, the poet’s agony.

A Moral and Material Crisis

Today, as you well know from the political news emanating from Manila, we are suffering anew and suffering aplenty, from a deep moral crisis in leadership that is not helping our material situation any. Our President, Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, was caught with her hand in the electoral cookie jar, and was on the verge of being ousted through either a forced resignation, another popular revolt, or impeachment, until she rallied her forces and allies and recovered ground for the time being.

The next year promises to be a politically tumultuous one for the Philippines, with the President’s credibility at an all-time low, and with a new energy and economic crisis in the offing. Our most basic, strategic problem is mass poverty and the injustice it breeds and which also breeds it. Our immediate challenge is to find the leadership that will galvanize us into a nation resolved to unite to help itself. We seem to be in grievous need of another Redeemer, but none has emerged as yet, which is what has been keeping Mrs. Arroyo in office.

In all this, journalism, not creative writing, has taken to the forefront of political engagement. We pride ourselves in having Asia’s freest – some would say most licentious – press, and again it has served the cause of public debate with riotous distinction. And over the past few years, Filipino journalists have paid the price for their audacity. According to the New York-based Committee to Protect Journalists, the Philippines is the “most murderous country in the world” for journalists – more than Iraq, Colombia, and Bangladesh – with 18 journalists killed in the line of work since 2000.

No Filipino novelists, poets, playwrights, or essayists have shared in this dubious distinction, and for good reason. For all the literary talent we think we have, it can be argued that creative writers really don’t matter in Philippine politics – certainly not as much they used to – because, to be hyperbolic about it, no one reads, no one buys books, and no one understands what we’re doing. In terms of the subtitle of this conference, we have a lot of knowledge, but little, if any, influence.

It’s a sad fact that in a country of over 80 million people, with a literacy rate of about 95%, a first edition for a new novel or book of stories even by an established author will run to no more 1,000 copies – which will take about a year to sell, and earn the author a maximum of about P50,000 (about 3,300 Malaysian ringgit) for a few years’ work. There’s no such thing as a professional novelist or poet in the Philippines, which makes it easier for writers of any worth to be sidetracked or co-opted by the government or by industry.

It’s ironic that Philippine literature’s political edge should be blunted not by timidity nor by censorship but by sheer logistics or market forces. The simplest and clearest reason many Filipinos don’t buy books has to be poverty, with the price of an average paperback being higher than the minimum daily wage prescribed by law. Even among the middle class readers whom we expect to be our major market, we face stiff competition for the same disposable peso from, say, John Grisham.

But perhaps we writers ourselves are partly to blame, for distancing ourselves from the mainstream of popular discourse. Politics is nothing if not the domain of the popular, and the very fact that many of us write in English is already the most distancing of these mechanisms. The question of language has always been a heavily political issue in multilingual Philippines, where some regionalists still resent the choice of Tagalog as the basis of the new national language Filipino in 1935, and where English is reacquiring its prominence not only as the lingua franca and the language of the elite but as our economic ticket to the burgeoning global call-center industry.

The inadequacy of English as a medium for the creative expression of native experience was put forward by such poets and critics as Emmanuel Torres (quoted by Gemino Abad) who said in 1975:

The poet writing in English… may not be completely aware that to do so is to exclude himself from certain subjects, themes, ideas, values, and modes of thinking and feeling in many segments of the national life that are better expressed – in fact, in most cases, can only be expressed – in the vernacular.

With this, Abad (himself a poet and critic) vehemently disagreed, contending that:

If anything at all must needs be expressed – must, because it is somehow crucial that not a single spore nor filament of the thought or feeling be lost – then one must needs also struggle with one’s language, be it indigenous or adopted, so that the Word might shine in the essential dark of language. Otherwise, the vernacular, by its own etymology, is condemned to remain the same slave born in his master’s house.”

It’s an old debate that those of us who inhabit the postcolonial world have dealt with and engaged in for ages. But to cut that long and familiar story short, even if Dr. Abad were correct in claiming for English the ability to convey every nuance of our native experience, the fact remains that any kind of writing in English – least of all creative writing – will reach a severely limited number of Filipinos. What may be fine for poetry could be absolutely useless if not even counter-productive in politics.

Politics, of course, is more than a numbers game, especially where the few have always ruled the many. Political change in the Philippines has historically been led by the middle class, from the Revolution against Spain of 1896 to the anti-Marcos struggle of the 1970s and the 1980s to the Edsa uprisings of 1986 and 2001. Therefore, one might argue that English is, in fact, the language of reform and revolt in the Philippines.

But it is this same English-literate middle class – our potential readership – that is the strongest bastion of neocolonialism in the Philippines, blindly infatuated with Hollywood, hip-hop, and Harry Potter, keen on trading the local for the global, opportunistic in its outlook and largely unmindful of the social volcano on the slopes of which it has built its bungalows. As I often say at home, our rivals on the bookshelves are not each other, but Tom Clancy, Danielle Steele, John Grisham, and, yes, J. K. Rowling.

I’m certainly not suggesting that we stop patronizing these authors. Rather, if we are to be interested at all in readership and consequence, we Filipino writers should re-examine whether there are huge unvisited corners of the popular imagination that we have failed or even disdained to reach.

In a recent lecture on “Our Revolutionary Tradition,” the essayist and sometime government minister Adrian Cristobal (who incidentally attended Baguio as one of its youngest participants) observed that:

English is not the enemy, it’s the absence of a common language. We can, as intellectuals – whether writers, journalists, orators, politicians – fulminate as much as we can against an unjust social order – but it’s doubtful that we can move out multitudes to revolution. We cannot touch their minds and hearts because we speak in a foreign language, because despite all our protestations, we are also of the elite by virtue of our alien education. We gain prestige, we can even achieve glory, but we shall remain out of touch because we cannot reach the hearts and minds of the many. For to reach the heart of the Filipino requires the discovery of its language.

Death by SMS

Indeed it may not even be the language but the medium and the mode of creative expression that we should be looking at. Given the near-constancy of turmoil in our politics, it’s hardly surprising that new forms of protest literature have arisen – chiefly, the SMS or “text” message as it’s more popularly known in the Philippines. According to industry reports, “at least 200 million text or SMS messages are sent every day in the Philippines – that’s more than two for every Filipino and earns the country its reputation as the world’s SMS capital.”

The extreme fluidity and the cumulative force of these text messages brought a flood of people to the streets and helped depose President Joseph Estrada in 2001. The opposition’s weapon of choice was comic ridicule in the form of the “Erap” joke – “Erap” being the presidential nickname – which circulated with lightning speed, cementing the public (or more accurately the middle-class) perception of its leader as grossly corrupt, incompetent, and therefore unworthy of continued support. The most popular ones addressed his alleged stupidity:

Q: Why did Erap stare at a bottle of orange juice?

A: Because it said ‘concentrate.’

Q: Why can’t Erap dial 911?

A: Because he can’t find the eleven on the phone!”

Others played up his fabled venery:

A Philippine Airlines pilot tells Erap before landing: “Mr. President, we have begun our descent. Please fasten your zipper and return Weng to her upright position!” (referring to a PAL flight attendant rumored to be one of the President’s mistresses).

Ordinary citizens elsewhere would have been imprisoned or shot for such impertinence, but not in the Philippines. Given the numbers, repression would have been futile. More than a hundred million text messages would fly across the country at the height of the frenzy, most of them bearing another call to arms, or another joke to bring President Estrada down another peg. These text messages and jokes were reinforced by spoofs of popular songs, distributed on CDs that couldn’t be duplicated fast enough. It may be an overstatement to say that technology did Estrada in – Chairman Mao’s dictum about “people, not things” making the difference would be well worth quoting at this point – but what we call “Edsa 2” or “People Power 2” would certainly not have gone as smoothly as it did without some digital lubrication.

Today, with Mrs. Arroyo, the situation is somewhat different, although it’s ironic and telling that her credibility and Presidency are being undone by another technological imp – the digitized copy, in CD and transcribed PDF formats, of a damning series of wiretapped conversations President Arroyo was supposed to have had with an election commissioner who promised to deliver the votes she needed to win. These so-called “Hello, Garci” tapes (“Garci” being Virgilio Garcillano, the election commissioner in question) went through the Internet like wildfire, and became the subject of countless spoofs; for a while, a Website offering new “Hello, Garci” ringtones crashed because of the volume of demand. A flood of GMA jokes – like the old Erap jokes – swept the cellular networks (among them: “Clinton’s downfall was a cigar, GMA’s is Garci.”).

Like other examples of folk humor, these short, spontaneous, and often imaginative comic outbursts are, I submit, a new form of popular literature that empowers individual citizens and allows them to engage political authority in a manner that may not be directly confrontational and certainly not violent, but whose cumulative impact can wear reputations down as water does stone. A despot should have more to fear from text jokes, from messages forwarded to dozens of Hotmail and Yahoo addresses, and from a satirical comedy skit on TV, than from any novel or epic poem or three-act play. (This reminds us of Martin Esslin’s proposition that the dominant dramatic form today is the 15-second TV commercial, which contains all the elements of classical drama, delivered in a compact, compelling way.)

One of the interesting side issues that came up in the course of Congressional or parliamentary hearings on the Garci tapes was the question of originality and authenticity; in this digital age, was a digital copy itself, in effect, a new and legally acceptable original? Who was the author of the tapes who could be held liable for them? Were the characters in it and their acts subject to prosecution? Did spreading the tapes or even listening to them constitute a criminal offense? And, of course, given that the tapes and their transcripts remained unauthenticated by a credible third party during the whole brouhaha, what was fact, and what was fiction?

These, to me, were eminently political but also eminently literary questions, involving authorship, textual analysis and exegesis, publication and even copyright, if you will. The same questions and considerations apply to the responses the tapes provoked.

Fortunately for Mrs. Arroyo, and despite the protest resignation of ten of her Cabinet members, she was able to buy some time with the intercession of powerful allies, including conservatives in the Catholic Church, and also with the failure of a palatable alternative to emerge from the ranks of the opposition. With both sides having learned from two popular uprisings, passions have abated, fatigue has set in, old strategies and tactics haven’t worked, and most indications point to a bruising drawn-out war rather than another decisive skirmish on the streets. Perhaps it’s just as well for us, as the pause favors the novelist who takes the long, critical view over the editorialist with a quick prescription for the morrow. Those jokes and the deep wellspring of satirical humor that bred them need to acquire more permanence in a Great Filipino Comic Novel, which has yet to be written.

I’ve often remarked on this strange feature of our literary landscape, so far removed from our everyday reality as a people: the crushing humorlessness of much of our literature. We are a laughing, smiling people; we laugh even in the worst of times and the most perilous of moments as a nervous reaction and as a coping mechanism. We have had great comedians like Dolphy and comic heroes like Juan Tamad – dunces, tricksters, kind-hearted rogues, characters who survive by their wits no matter what. But when we write novels, it’s as if we were confessing to a priest or preaching from the pulpit instead of confiding in one another; our words suddenly acquire a numbing solemnity, a high seriousness that may yet be Jose Rizal’s most enduring and yet also most paralyzing legacy to his successors.

A few years ago, on a fellowship in England, I gave myself this task of writing what I planned to be a darkly comic novel about the plight of our millions of migrant workers overseas. I thought I was starting well – only to stop when I realized how the darkness and the grimness were slowly but surely overtaking my intentions. I remain convinced, however, that fresh comic insights – instead of belabored iterations of the sadness we already know – are the key to the revitalization of our literature, and that comic sufferance, not tragic suffering, may yet be the best nexus between Philippine literature and politics.

Jose Dalisay Jr.

Department of English and Comparative Literature,

University of the Philippines

This piece is based on an address to the 4th International Seminar on Southeast Asian Literature, held in Kuala Lumpur, 29-30 November 2005

Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia. Issue 8-9 (March 2007). Culture and Literature

References

“216 Filipinos detained in 1st round of Malaysia crackdown.” Asian Journal Online 3 March 2003. Accessed 12 September 2005 at http://www.asianjournal.com/cgi-bin/view_info.cgi?category=BN&code=00009747.

Abad, Gemino H. 1998. “Mapping Our Poetic Terrain: Filipino Poetry in English from 1905 to the Present.” The Likhaan Anthology of Philippine Literature in English, ed. Gemino H. Abad, 3-24. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press.

Bendeich, Mark. 2005. “Asia tries to put SMS genie back in its bottle.” Reuters UK, 1 September 2005. Accessed 10 September 2005 at http://today.reuters.co.uk/news/newsArticle.aspx?type=reutersEdge&storyID=2005-09-01T111318Z_01_NOA140129_RTRUKOC_0_FEATURE-ASIA-SMS.xml.

Committee to Protect Journalists. 2005. “The Five Most Murderous Countries for Journalists,” 2 May. Accessed 13 September 2005 at http://www.cpj.org/Briefings/2005/murderous_05/murderous_05.html.

Cristobal, Adrian. 2005. “Our Revolutionary Tradition.” Inaugural Plaridel Lecture, Writers Union of the Philippines. Manila, 27 August.

Dalisay, Jose Jr. 2001. “Showtime at EDSA.” People Power 2: Lessons and Hopes, ed. Thelma S. San Juan, 242-47. Pasig City: ABS-CBN Publishing.

Esslin, Martin. 1982. “Aristotle and the Advertisers: The Television Commercial Considered as a Form of Drama,” in Television: The Critical View, ed. Horace Newcomb. New York: Oxford University Press.

Guerrero, Leon Ma. 1951. “Our Choice of Heroes.” Sunday Times Magazine, 20 December. Accessed 12 September 2005 at http://www.jose-rizal.com/firstfilipino/choice04.htm.

Lacaba, Jose F. 2001. “Eman.” Araw: Philippine Art and Culture Today 1: 75-79.

Ordoñez, Elmer A. 2004. “Proletarian Literature.” Manila Times Internet Edition, 2 May. Accessed 11 September 2005 at http://www.manilatimes.net/national/2004/may/02/yehey/weekend/20040502wek3.html.

San Juan, Epifanio Jr. 2005. “Philippine Writing in English: A Bakhtinian Perspective,” 25 July. Accessed 12 September 2005 at http://www.geocities.com/icasocot/sanjuan_bakhtin.html.

Sison, Jose Ma. 2005. “The Guerrilla Is Like a Poet,” 23 August. Accessed 12 September 2005 at http://www.ctv.es/USERS/patxiirurzun/nueve/sison.htm.Tiempo, Edilberto. 1959. “The Challenge of National Growth to the Filipino Writer.” Comment 8: 91-96.