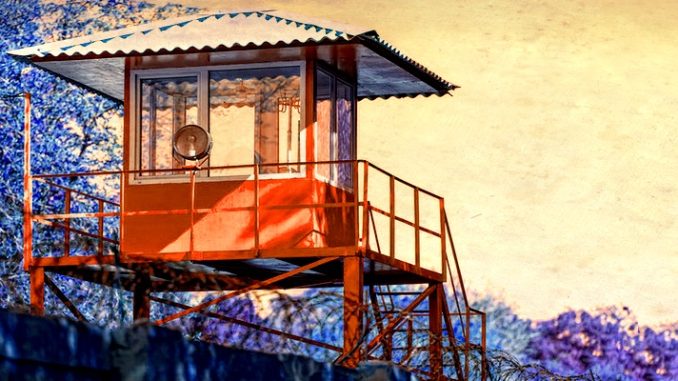

Many borderlands in Southeast Asia—in southern Thailand, East Timor, Papua New Guinea, Sulawesi, Aceh, southern Philippines, Myanmar—have become violent. In the peripheral spaces of Southeast Asian nation-states, people flee from horrific acts of violence committed by state forces, military units, border guards, police, vigilante groups, and armed guerrillas. In these violent borderlands, civilians are squeezed between military and paramilitary state forces on the one hand and armed guerrillas on the other (Amporn, this issue). Communal violence escalates in places where people of different ethnicities and confessions had learned to live as peaceful neighbors. People are suspected of being military informers or helping hands of armed opposition groups, and the consequent disappearances, abductions, tortures, and killings contribute to an atmosphere of fear. Nearly always, however, conflicts that are dubbed ethnic or religious reveal themselves to be conflicts of resource competition, the violence sparked by the huge interests at stake in the illegal economy defended by powerful groups within the nation-state far from the eyes and “civilization” of the center (Wadley and Eilenberg, this issue). As we will see in the features of this issue, agencies of the state are eager participants in the border economy as well, and their policing of the border helps to sustain a profitable situation for the exploitation of migrant labor.

People at the border are at unease with the nation’s centers, by whom they are considered bandits, delinquents, or presently “terrorists.” In southern Thailand and southern Philippines, for example, Islamic schools have come under the scrutiny of secret service branches, aided by special military assistance of the United States and its allies. Governments profile Islamic teachers and threaten to close Islamic schools which refuse to collaborate with the government, thereby building up files of potential terrorists. For the governments of Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, and the Philippines, the proclaimed war against terror is a welcome opportunity to increase control and pressure on civil society in the borderlands, especially its Islamic parts (Horstmann 2005).

And yet, even formidable military forces are not able to achieve full control at the edge of the nation-state. Where people in the past avoided enslavement and conscription by escaping to the hinterlands, high mountains, or wide sea (Scott 1990, 1998), people today slip to the other side of the porous border. The northeastern Malaysian states of Kelantan, Perak, Perlis, and Kedah became the natural exile of Patani Malays fleeing persecution by the Thai state in the 1930s, the 1960s, and the current escalation of communal violence. Especially in Kelantan and Perak, Patani Malays were allowed to establish villages with the tacit understanding of the Malaysian state. But today, insurgent leaders are pursued deep into Malaysian territory, causing them to flee as far as Europe and the Middle East. People say they fear arbitrary state forces more than the armed fighters of radical Islamic organizations, but the army and police themselves do not feel comfortable in border villages where they have to expect snipers and ambushes.

The shocking escalation of violence in many borderlands has brought hidden geographies of the state into the limelight of the world’s media and academia. Nevertheless, many of these regions remain virtually unknown. In the borderland of Bangladesh, Burma, and India—one of the least known places in South and Southeast Asia—the protest of Bangladeshi, Burmese, and Indian people against gas exploitation, forced labor, and loss of resources and land has come to the attention of a global public (van Schendel, this issue). But the atrocities committed by the Tatmadaw (Burmese army) in the Karen, Shan, and Rohingya borderlands and the consequent flight of the masses into neighboring borderlands remains virtually unnoticed.

In this issue on states, peoples, and borders, the relationship between people and the state is put into a new perspective. Anthropologists have long focused their scholarship on marginal ethnic minorities in the peripheries of Southeast Asian states, but they have tended to see these as communities with clearly inscribed identities. The features and articles in this issue take borders into full account in identity formation. Contributors are interested in what the border and its related order do to the people and what the people do to the border, including its border guards. The authors in this volume do not take the border for granted, but look for the transformation of the political ecology of the border in the practices of the state and of people who, depending on their location, may be clients or enemies of the state.

The research in this issue distances itself from the notion of fixed, unchanging communities and embraces a perspective in which people in the borderland are subject to constant classification by the border regime and have to bear the consequences of the border every day. For example, the Akha, Lahu, and Yao in the mountainous Thai-China-Lao-borderlands have to adapt to a classification regime of people, culture, and natural resources whereby some so-called tribal peoples do not get much more recognition than cattle. People regarded as subverting the dominant order of the state are sometimes pushed to the brink of extinction, such as the Cham in Cambodia, the Rohingya in Burma, and the Thai-Lüe in Yunnan (Kiernan 1996; Davis 2004 and this issue; van Schendel, this issue). Armies take pains to destroy the Islamic mosques of the Cham and Rohingya and the Buddhist monasteries of the Thai Lüe to rip out the roots of ancient cultures. While some mosques in Burma and monasteries in Yunnan have been reconstructed, thousands of Shan, Karen, and Rohingya people have been forced by military operations to cross the border into neighboring states as refugees.

But the border can by no means be limited to a territorial line. It extends deep into the heart of the national territory—into the center itself—extending to every agency where the state deals with the alien, the illegal, the migrant, the refugee, and the political dissident detained in high-security prisons or detention camps. While the Bangladeshi state initially promised villages for the Rohingya refugees, none materialized and the Rohingya had to settle in UN-supervised refugee camps. Some have been detained in Bangladeshi prisons for crossing the border illegally. Likewise, the Karen, subject to the whim of the Thai military and border patrol police, are located and relocated in unsafe locations adjacent to the Thai-Myanmar border where they are accessible to cross-border raids by the Tatmadaw (Rajaram and Grundy-Warr 2004). In the monsoon season, provisions are nearly impossible to transport to these isolated places in the forest, but the Karen refugees are kept there because the Thai military fear they will slip out of the camp, enter further into Thailand, and disappear into the cities. Karen refugees are regarded as temporary aliens who should return to Myanmar as soon as possible.

The lives of others have been affected differently by borders. The Orang Laut have a history of governing the sea, its marine resources, and its travel routes, but they were gradually impoverished with the merging of powerful states around them (Chou, this issue; Benjamin and Chou 2002). In this issue, we are concerned with re-centering the spaces in between states, bringing border zones into the center of analysis, and finding a level of analysis in between the local and the global in anthropology. The contributors insist that, far from a borderless world in which the nation-state is doomed to disappear, we live in a world in which the nation-state’s border as a classifying machine is rapidly gaining in importance. Second, the border not only shapes folk identities, but also classifies people in a hierarchy of value, as argued brilliantly by Michael Kierney (2004). This argument can be applied to Southeast Asia, but let me first illustrate the point with a European example.

Lampedusa—a tiny island in the Mediterranean where a handful of inhabitants used to make a living from fishing until the tourist boom arrived—is the southernmost point of Italy, only one hour by ship from Tunesia. Tourists come to relax on Lampedusa’s fine beaches, but migrants also arrive in small boats every day when the sea is quiet. Many of them have a long, arduous journey; some even traverse the Sahara. Others never arrive, drowning in the sea or dying of thirst. Arriving migrants are immediately put into Lampedusa’s detention camp, from which they are transferred to other Sicilian or southern Italian camps. Many are deported to Libya, without even being informed of their fate. Hundreds of people are deported in this way without any recognition of their existence as human beings with personal names. 1

Similar detention camps for foreigners are beginning to emerge in Australia, Malaysia, and Thailand, where people escaping from violence, poverty, or both are confined outside the realm of basic human rights (Rajaram and Grundy-Warr 2004). The governments of Thailand and Malaysia are not interested in the migrant as a human being; they limit themselves to confinement of the migrant body. While much of the work on borderlands has focused on the shifting of human identities, the question of the refugee concerns the elimination of basic human rights as the key effect of the border on people who have to cross it to survive.

Border zones are regarded by the state in a negative light, as zones of political instability and subversion. This insecurity justifies large military budgets, and the rise of drug addiction along the trade routes provides the pretext for government intervention. In January 2003, newly elected Thai prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra proclaimed a war on drugs in which police forces were given carte blanche to kill people who might be affiliated with drugs. In just one year, more than 2000 people were killed by police death squads. Governors and police forces were pressured to come up with black lists: People on the black list were summoned to the district office to confirm their identity before being murdered the next day; the killers operated from motorcycles, wearing plain clothes and masks to avoid identification. That people were effectively removed from the realm of basic human rights was of no concern to Thaksin, who simply stated: “In a war, there are dead people… these people deserve to die.” In particular, the government ordered summary executions of alien Burmese who operated drug cartels on Thai territory. Being wholly outside Thai law, these aliens had little chance of mercy. And as Thaksin’s campaign targeted people everywhere in Thailand, this was a case in which human rights abuses common to the border were imported and generalized to society as a whole.

Borderlands are therefore a realm outside the order of the state, yet integral to it and its economy, of which a large share is illegal. Like Batam in the Singapore-Indonesia borderland, many border-zones are the Wild West of their respective regions, providing vacuums in which illegal multi-million dollar businesses boom. Drug rings on the Thai-Myanmar border involving hill minorities, border guards, and corrupt officials have flooded Thailand with amphetamines. Heroin is smuggled via Bangladesh and India for the North American and Western European markets (see van Schendel, this issue). Governments may tolerate these operations, they may profit from some of the rackets, or they may be actively involved to the extent that it is impossible to distinguish between legal and illegal domains. 2 This is particularly true for large logging operations in Borneo, where logs are smuggled into Malaysia (see Wadley and Eilenberg, this issue). In another example, night-clubs may be closed by the Islamic ruling party in Kelantan and Malaysian Muslims tried for violations of sharia law, but crossing the border to Thailand brings the sex-tourist into another world, one in which tour groups arrive daily to visit massage parlours or engage in gambling and other practices that are forbidden, risky, or expensive at home. Casinos are often found in the spaces between countries such as Thailand and Laos on the banks of the Mekong River, or on Burma’s southern border, providing a playground for high society. Towns like Sungai Golok on the Thai-Malaysian border would be sleepy places without the cross-border smuggling and markets, the drug trade, the hotels and prostitution.

This hierarchy of value, as expressed in the “good times” of tourists who temporarily leave the rigid orders of Malaysia and Singapore, is also the reason for labor migration and cross-border marriage. Well into the 20th century, people moved in many directions through the borderlands of Southeast Asia. It is only in the wake of the post-colonial nation-state that the possession or lack of citizenship has had dramatic consequences in people’s lives. As non-citizens, the Rohingya in the Burmese-Bangladeshi borderland can be expelled from Burmese territory. Although many people in Malaysia have Philippine or Indonesian ancestors, present-day Filipinos and Indonesians are regularly deported or forced to leave to avoid arrest.

In cross-border migration, unequal gender relations and border regimes overlap in the hierarchy of value. The case of Muslim women from Thailand working in Malaysia is exemplary. Instead of accentuating their identity along kin or religious lines as sisters or Muslims, Thai-speaking Muslims hold themselves apart from Malays, who perceive them to be influenced by the Thai Buddhist cosmology. Still, many women from Thailand are drawn to work in Malaysia to improve their lives, and many find spouses there. Going back and forth between “home”—Thailand—and their new home in Malaysia, they keep tight to their cross-border networks of kin and friends, which are crucial to mobilize support in difficult situations (Tsuneda, this issue).

The entrenchment of borders with their attendent hierarchies of value constitute border regimes. The Thai and Malaysian economies make huge fortunes by exploiting the fragile situation of Burmese or Indonesian migrants who are denied the security of staying legally and/or permanently. Regular police raids among migrant populations protract this regime: If workers of alien origin dare to protest low wages, the police may arrive to beat them up and change their status from laborers with work-permits to illegal and deportable aliens. 3 The regime is most profitable for Thai employers and police, who might steal the migrants’ wages before deporting them. Sexual abuse and beatings are rampant in prisons and detention camps. And yet, despite these pressing problems, migrants and refugees will continue to come in large numbers.

Much research needs to be done on the specific political ecology of individuals and states in Southeast Asian borderlands. Exciting research is already emerging, showing how loopholes and vacuums in the largely invisible borderlands create specific border regimes characterized by hierarchies of values. Brokers emerge who use the border regime to their advantage. Human trafficking and smuggling result from the huge wealth disparities between nations and the protracted conflicts that force people to cross borders. The contributors to this issue, besides reviewing their fields, show that there are parties who have an interest in the perpetuation of conflict, the illegal border trade in all manner of goods, and the exploitation of illegal labor. Borderlands are by no means marginal to the world or to anthropology. Studying them may create opportunities to move away from state-driven methodologies and terminologies. Borderlands provide a privileged situation for anthropologists to study the strategies used by governments to discipline and survey their populations, and also the practices used by people to resist them, including flexibility in affiliation and border-crossing supported by networks in two or more countries. Anthropologists might use their research on states, peoples, and borders to refute much of the received wisdom of cultural anthropology. No space is more in flux than these border landscapes .

Alexander Horstmann

References

Benjamin, Geoffrey, and Cynthia Chou. 2002. Tribal Communities in the Malay World: Historical, Cultural and Social Perspectives. Singapore: ISEAS.

Davis, Sara. 2005. “Premodern Flows in Postmodern China: Globalization and the Sipsongpanna Tais.” In Centering the Margin. Agency and Narrative in Southeast Asian Borderlands, ed. Alexander Horstmann and Reed L. Wadley. Oxford: Berghahn Books.

Heyman, Josiah. 1999. States and Illegal Practices. Oxford: Berghahn Books.

Horstmann, Alexander, and Reed L. Wadley, eds. 2005. Centering the Margin: Agency and Narratives in Southeast Asian Borderlands (Anthropology of Asia Series). Oxford: Berghahn Books.

Kiernan, Ben. 1996. The Pol Pot Regime: Race, Power, and Genocide in Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge, 1975-79. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Kierney, Michael. 2004. “The Classifying and Value-filtering Missions of Borders.” Anthropological Theory 4, 2: 131-56.

Palidda, Salvatore. 2005. “Migration between Prohibitionism and the Perpetuation of Illegal Labour.” History and Anthropology 16, 1: 63-73.

Rajaram, Prem Kumar, and Carl Grundy-Warr. 2004. “The Irregular Migrant as Homo Sacer: Migration and Detention in Australia, Malaysia and Thailand.” International Migration 42, 1: 33-64.

Scott, James C. 1990. Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Scott, James C. 1998. Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Notes:

- Similarly, Palidda (2005) argues that increased border patrolling does not decrease but perpetuates illegal labor, noting that the policing of the U.S.-Mexican border has criminalized labor that is vital to the American economy. ↩

- See Heyman (1999) for an excellent framing of the relation between state and illegal practices at the border. ↩

- The author witnessed one such brutal clampdown on Burmese migrants while attending a workshop in Chiangrai on Borders, Security and Migration in Europe and Southeast Asia in December 2003. ↩