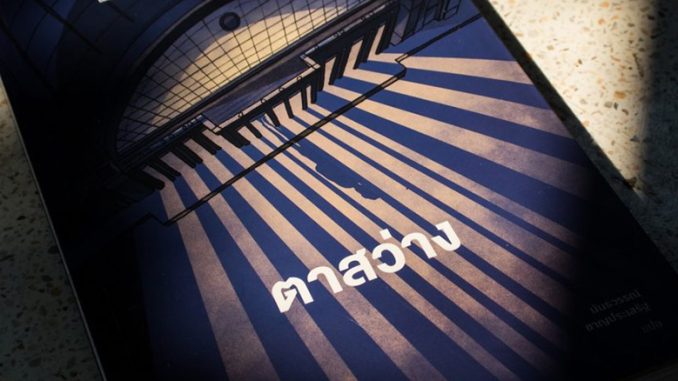

Title: ตาสว่าง [Ta Sawang]

Author: Claudio Sopranzetti, Sara Fabbri and Chiara Natalucci

Translation (to Thai): Nanthawat Charnprasert

Publisher: Reading Italy, 2020

Ta Sawang is a graphic novel by a group of Italian anthropologists. There are different ways of translating the title of this book; it is either “Eyes Brightened” or just “Enlightenment”. Either way, it indicates a moment in one’s life to wake up to a political reality and truthfulness, which was entombed in illusion. The novel is based in part on a true story—the details of which were gathered during the author’s long years of interacting with Thai politics. It is easy to read and serves as an excellent background of the recent political developments of Thailand.

Ta Sawang begins with a poetic statement; “I am waking up to a giant greedy octopus. It is devouring rice fields, rivers, houses and peoples. It took away my eyes. Albeit blind, I can still see. I am enlightened.” Saying this is a middle-aged Thai man, from Udonthani, a province in the far-flung northeast region of Thailand, known as Isan. His name is “Nok”, meaning “bird”, who is blind. Living with his wife in crowded Bangkok, Nok is a leading character of this novel whose dream of building a better life in the city shattered because of his lack of access to political resources.

Like many of his fellows from the periphery, Nok arrived in Bangkok to fulfil his dream. Being unskilled and uneducated however, he had no choice but to enter a labour intensive workforce. Exploited, Nok became enslaved by modern-day’s businesses.

The book travels back and forth different periods of Nok’s life, juxtaposing the present with the past, in parallel with what happened in the political domain. Nok is a typical Thai man from a rural province. Poor but hardworking, Nok found his living a struggle. As this graphic novel portrays, for a long time, the Thai economic development had been uneven, with an evident widening of a gulf between urban and rural provinces. Power was strictly centralised and wealth was concentrated in Bangkok. A political system long dominating the country had left remote regions strikingly underdeveloped.

Nok got married with Kai who was also from his village. The night before their wedding, the radio broadcast a breaking news: The government of General Suchinda Kraprayoon, in 1992, launched deadly crackdowns on protesters in an incident now called, Black May. The calamity ended thanks to the royal intervention. This is an important message riddled throughout the novel in regards to the periodic disruptions in politics at the hands of the Thai power holders and at the expense of democracy.

Nok got married with Kai who was also from his village. The night before their wedding, the radio broadcast a breaking news: The government of General Suchinda Kraprayoon, in 1992, launched deadly crackdowns on protesters in an incident now called, Black May. The calamity ended thanks to the royal intervention. This is an important message riddled throughout the novel in regards to the periodic disruptions in politics at the hands of the Thai power holders and at the expense of democracy.

Hardship caused by the underdeveloped state of Isan and the problem with Thai democracy that had blocked an access to political resources among the poor, Nok was compelled to leave his family behind to search for a job opportunity elsewhere. Being miles away from home, Nok worked extremely hard and counted the day for a family reunion. But disaster stuck. This time, it was the 1997 financial crisis. The booming economy turned to bust. Suffering a new setback, Nok almost gave up on his life in glossy Bangkok.

Strolling into politics, in 2001, was a new breed of politician, Thaksin Shinawatra. Unlike his predecessors, Thaksin crafted an idea that was to empower the marginalised residents of the north and northeast regions, disregarded by the traditional political elites. Propelling a myriad of populist policies, the Thaksin administration was eager to improve their livelihood to catch up with the world of the millennium.

Nok was a recipient of benefits under the Thaksin government. He now switched to working as a motorcycle taxi driver, a seemingly lucrative job in the ever so jammed Bangkok. That Thaksin opened up a political space for the underprivileged peoples like Nok was a part of a revelation. Never before did a politician care for the wellbeing of his supporters. To Nok, Thaksin proffered not just an economic opportunity, but also a sense of political belonging that had been lacking in his consciousness.

By now, his son, Sun, had grown up. Nok was surrounded by his family members and close friends—all of whom felt they were indebted by Thaksin’s policies. They formed a force, together with other supporters of Thaksin, that drove their favourite party, Thai Rak Thai, to the finishing line in the second election. Thaksin returned to the government in 2015 with a landslide victory, becoming the only prime minister of Thailand to have served a full four-year term.

But Thaksin’s success did not last. And Nok’s excitement of an upgraded life was short-lived. Coups are a part of Thai culture. Throughout Nok’s adulthood, he had witnessed several of them. He witnessed it again in 2006. This time, the coup robbed him of his beloved prime minister. The arrival of Thaksin already made Nok ta sawang. However, what came after the topping of Thaksin was a total enlightenment.

Thaksin’s ousting left a power vacuum to be filled with political uncertainty, and in 2010, political violence. The political scene was set on an irony. Red-shirt supporters of Thaksin from the poorest regions strove to colonise Bangkok. The financial district at Rachaprasong was occupied. Next to Louis Vuitton were protesters’ camps. The protest stage turned its back to the mega mall Central World.

The government of Abhisit Vejjajiva ended months of protest with brutality. In May 2010, it opened fire to the protesters, leading to 99 people killed and more than 2,500 injured. Nok was among those injured. He lost his sight and became blind. Here, the book ingeniously uses the term ta sawag to mean “enlightened”, even if one is blind. Yet, for Nok, the darkness gets brighter.

The book mentioned in passing the role of the monarchy in the protracted Thai crisis. Because the book is translated in Thai and sold in Thailand, criticising the monarchy is therefore not an option. But this minor flaw of leaving the monarchy out of the crisis is compensated by an excellent narrative of the Thai political life found in this book, enliven by fine drawings that succinctly reflects the trauma of Nok, and many others in the same situation.

Reviewed by Pavin Chachavalpongpun

Pavin Chachavalpongpun is associate professor at Kyoto University’s Center for Southeast Asian Studies. He is the chief editor of Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia.