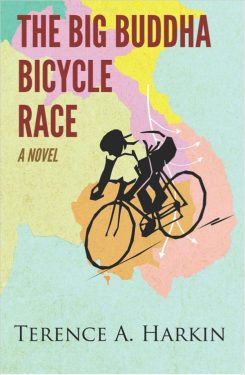

Title: The Big Buddha Bicycle Race

Author: Terence A. Harkin

Publisher: Silkworm Books (2017), 396 pages

In cyberspace, the word Vietnam comes up as a metaphor for the threat of annihilation followed by a disastrous undoing. Like the bits of “quantum information” used by Chinese intelligence in information processing, it’s an example of entanglement – the ability of separated objects to share a condition or state – which Einstein dismissed as “spooky action at a distance”.

This strange semantic, gnoseological reflection is induced by “The Big Buddha Bicycle Race”, a novel by Terence A. Harkin. The book is ostensibly a Vietnam “war diary”: Harkin served in the US Air Force with the 601st Photo Flight at Ubon Royal Thai Air Force Base, an obscure air base in upcountry Thailand, during the latter years of the war. But, on closer inspection, the war is just one of many spooky actions woven into a “wilderness of mirrors”, to quote James Angleton, chief of CIA counterintelligence from 1954 to ’75.

Perhaps because the places, characters and stories do not simply make up a war memoir. This book is a mirror onto many lives. The bicycle in the “Big Buddha Race” is a time machine. For those there at the time, it’s a means of soul-searching. Every page arouses a memory, a bitterness, a sweetness, a lament for time lost: maybe for a song, another book, an author, a film, an event, a slogan. It was a formidable time in culture and counterculture, Sex & Drugs & Rock & Roll, a time when conversations like this took place:

“Who’s Jack Kerouac?” asked Dave.

“He’s the beatnik writer dude who gave Dennis Hopper the idea for Easy Rider,” Tom explained.

Featuring the existential meanderings of young protagonist Brendan, the alter ego of author Terry, the novel is another “Heart of Darkness”-style narrative, one that could only happen in a theatre like the Mekong basin, between Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos. This small, secluded country (in the centre of the book’s cover) crossed by the Ho Chi Minh Trail supply route between North and South Vietnam, was targeted by gunships like the one Terry himself served on. It is also where “Air America” operated, the CIA-operated airline made famous by the eponymous Mel Gibson movie about an agent transporting opium to Vientiane on behalf of an Asian general seemingly based on Vang Pao.

Featuring the existential meanderings of young protagonist Brendan, the alter ego of author Terry, the novel is another “Heart of Darkness”-style narrative, one that could only happen in a theatre like the Mekong basin, between Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos. This small, secluded country (in the centre of the book’s cover) crossed by the Ho Chi Minh Trail supply route between North and South Vietnam, was targeted by gunships like the one Terry himself served on. It is also where “Air America” operated, the CIA-operated airline made famous by the eponymous Mel Gibson movie about an agent transporting opium to Vientiane on behalf of an Asian general seemingly based on Vang Pao.

Another key player in this scenario was Anthony Poshepny, known as Tony Poe (whom Terry met 1987). He was military adviser to the forces of Vang Pao, who may have been the inspiration for Colonel Kurtz in “Apocalypse Now”.

Throughout this story, Laos has been the victim of a minor error, which may seem trivial in History, but is significant of the time. The error is reiterated in Harkin’s novel, though he is not guilty of it. Tom Robbins described it in “Villa Incognito”, a colourful novel that turns the nightmares of war into a psychedelic dream: “Around 1960, when events in that small Southeast Asian nation forced Western media to start paying attention to Laos, the Associated Press, networks, and news magazines decided that it would tax the American intellect—rigid yet porous—to comprehend that Lao was the adjective form of Laos, and, always preferring the dumbing-down of an audience to challenging it, they invented the term Laotian, a rather ugly (…) word”.

But let’s not get lost in the “wilderness of mirrors” of a History that is now romanticised in the curiosity of tourists. This book sets the “American war”, as it is called in Vietnam, against Cold War geopolitics in Southeast Asia. But the author adds his own twist to Kissinger’s version of events. As is the case in a description of the Domino Theory much feared by American strategists at the time.

“Here it’s a life-and-death gamble. Imagine a worst-case scenario and the North Vietnamese Army ends up occupying Northeast Thailand? What would they do to a bar girl who had been sleeping with the enemy?”

In this twist of scenes and analyses, with its “spooky action at a distance”, Harkin’s novel creates an entanglement effect between past, present and future: the fears created by the Domino Theory resound today with new players in what has been called a “New Cold War”. Whereas the local Thai Communist insurgents of the time are depicted as the ghosts of today’s Thai generals. The bicycle race referred to in the novel’s title and ending unconsciously anticipates or recalls the cult of the bicycle in contemporary Thailand.

Current inhabitants of Southeast Asia will enjoy spotting other similar situations and reincarnations of characters. From this perspective, Harkin’s novel is also a classic diary of old Asian hands and expats in Southeast Asia. It could even be seen as a prequel to those journals, foreshadowing their adventures and misadventures, vices and stereotypes. And especially their addiction to sex. These days the syndrome can be caught in the red-light districts of Bangkok or Pattaya but is often turned into a fatal attraction in Isan, Thailand’s poorest, northeast region, where the book is set, where the Big Buddha Bicycle Race takes place and where the bar girls come from. Many expats follow them back there, hoping for not just sex but also to find a woman to look after them.

In the end, every fantasy turns out to be an illusion. As Terry reveals at the start of the book. “It must have been a hallucination… How can I trust dream-visions that keep floating up from the murky depths? Hasn’t my memory been obliterated by drink and drugs and the passage of time?”

In a world where saiyasat, the supernatural, is deeply rooted in the collective unconscious, the only important distinction is not between reality and dreams but between preta, or ghosts, and nimitti, hallucinations. Brought on above all by the diverse visions of life that we face.

Reviewed by Massimo Morello, a Bangkok-based journalist