Established in 1913, Singapore’s Communicable Disease Centre (CDC, formerly known as Middleton Hospital), was long in the making. Its gestation over two decades highlighted the question of government responsibility – colonial or municipal – for infectious disease control. Socially, the hospital underlined the need to persuade Asian patients to seek treatment, rather than hide and spread their illness.

The genesis of CDC was a key moment in colonial Singapore. It contributed to a slew of legislative changes in 1907 that expanded the municipal commission’s responsibility for public health and housing in the town. However, the new hospital was built at Moulmein Road only after more preferred sites were turned down by landowners and residents. Its origins also revealed social divisions between Europeans and Asians, and even within the Asian community: upper class Asians, women and children previously avoided the infectious disease hospital. CDC sought to bring European, Eurasian and Asian cases under one roof, but this ideal was not fully realised.

A Dismal State of Infectious Disease Control

The state of infectious disease control at the end of the 19th century was dismal, and the need for a hospital dire. There were a plethora of small, inadequate and unpopular institutions. The Quarantine Station on St. John’s Island screened immigrants arriving by ship and had a camp for contacts of infectious cases, but it was unsuitable for patients residing in Singapore. The best institution for residents was the General Hospital (GH, which became the Singapore General Hospital in 1926), but after 1884 its dilapidated infectious disease wards were moved to Balestier. Henceforth, GH served only European and Eurasian patients, for whom a new Smallpox Hospital was built within GH in 1893.

The Asian community was treated in Balestier in the vicinity of Tan Tock Seng Hospital (TTSH), the privately-run Pauper Hospital which had a small ward for infectious diseases. Municipal records refer to a separate facility at Balestier Road, variously known as the Infectious Diseases Hospital and Quarantine Camp, the Smallpox Hospital or the Hospital for Contagious Diseases. Evidently from this multitude of place names, the facility was not a proper hospital.

In reality, only the seriously ill members of the male Asian working class arrived at these wards and camps. Numerous cases of infectious diseases were hidden from the official gaze and their total yearly number was under-reported. Although there was a ‘Big 3’ of dangerous notifiable diseases – smallpox, bubonic plague, and cholera – in practice, sick persons commonly fled from their houses to another part of the town, or were ejected by their landlords. Sometimes, the ill were moved by rickshaw and dropped off a short distance away from the hospital, and the bodies of the dead were occasionally dumped in the street. In 1899, Alex Gentle, the president of the municipal commission, admitted that upper class Asians, women and children possessed a ‘fear of injury’ towards the Balestier Road facilities. 1

Asian fear of the colonial hospital had a self-reinforcing effect: the more often patients died there, the greater the predisposition to avoid the hospital. The colonial government and the commission frequently failed to contain infectious diseases in the town. Singapore suffered four outbreaks of smallpox and five of cholera between 1892 and 1911. Patients with infectious diseases frequently died in the hospitals, but also in the streets and unknown to others in their own homes.

Struggle for the Hospital

A properly-equipped facility would break the vicious circle. But who would fund it? The colonial government demurred, stating that a large part of its budget was devoted to military expenditure. The municipal commission which administered the town, where infectious diseases were most prevalent, gave priority to other matters such as water supply and disposal of night soil and refuse.

Over twenty years, the colonial government and municipal commission passed the buck back and forth. In 1886, Ordinance XIX made the isolation of infectious diseases liable to become epidemics mandatory, and the government wanted the commission to take up this role. Eventually, in 1893, the commission agreed, but not without submitting a host of conditions. It would deal with dangerous infectious diseases in the municipality, provided that government hospitals remained free of charge, the police (part of the government) continued to enforce patient isolation in their homes, and the government continued its quarantine work at the immigrant depots. The commission could interpret its role narrowly because the colonial government was responsible for health matters in Singapore, while the Municipal Ordinance did not specify the commission’s health work within the municipality.

This unsatisfactory arrangement persisted as the incidence of infectious diseases grew. In 1895, the principal civil medical officer T.S. Kerr urged the government to build a new infectious disease hospital like the one at Province Wellesley, which had helped contain a smallpox outbreak that year. Two years later, the commission bought a disinfecting chamber from Britain to disinfect belongings of infectious disease patients, which was placed at the junction of Rangoon Road and Balestier Road.

This, the government deemed, was not enough. In 1899, it tried to press the matter, calling for a plan for improved accommodation for Asian patients with infectious diseases. Its principal civil medical officer and colonial engineer duly visited the quarantine camp at Balestier Plain and the adjoining hospital for infectious disease, occupied by Chinese, Malay and Japanese patients, both male and female. The visitors surmised that the Malays to be ‘respectable people’, some of whom were living there with their families, and all the patients were satisfied with their accommodation and treatment. 2 They attributed the Asians’ reluctance to come forward for treatment not due to poor hospital accommodation but ‘fear of the unknown’. 3

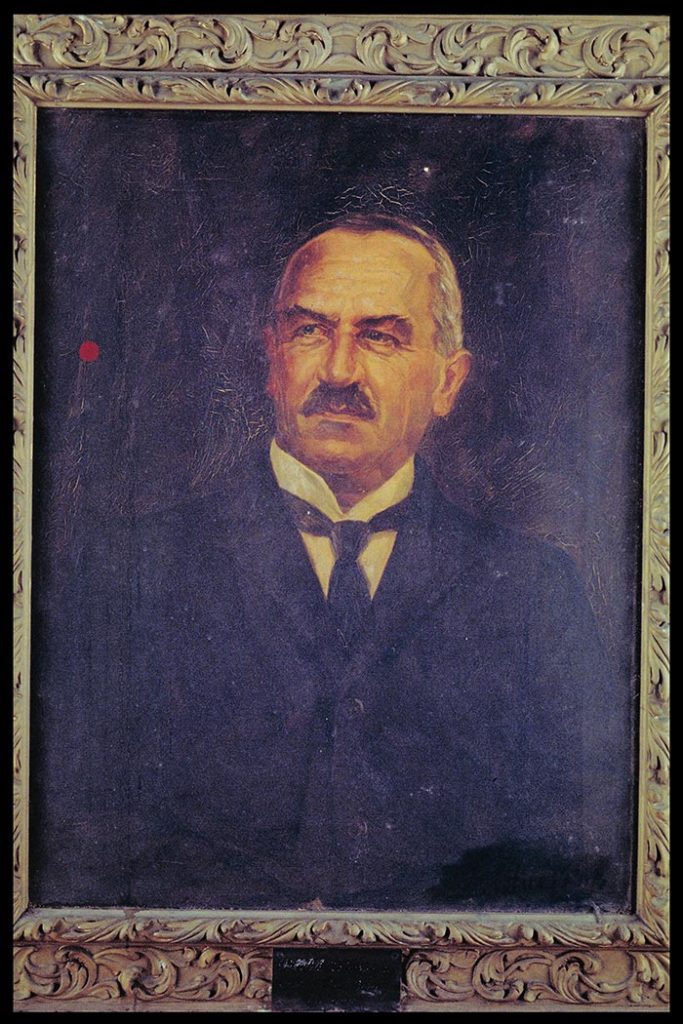

The sole dissenting voice was Dr W.R.C. Middleton, the municipal health officer, who protested that the facilities, with walls and floors ‘impregnated with the germs of diseases treated there’, were plainly not suitable for upper class Asian patients. 4 However, the Governor of the Straits Settlements, Charles Mitchell, decided that ‘it is not desirable to erect a superior class of hospital for infectious diseases at Balestier Road’. 5 The commission would not be moved until the Municipal Ordinance was amended to make it responsible for municipal health. Over the next few years, TTSH unhappily bore the costs of treating infectious diseases.

Calls for a better infectious disease hospital grew within the government. In 1904, W.J. Napier, a member of the Legislative Council, urged the government to build a new hospital as the commission had no money. Even the European ward for infectious diseases at GH was better known, he said, as an ‘obstruction to golf’, and he reminded the council of the case of a man who died of his illness while the government and commission haggled over responsibility for his hospital fees. 6 The Colonial Secretary C.W.S. Kynnersley disagreed, pointing out that the hospital would ‘invariably’ be the commission’s charge, as was the case in Britain. But it would be built, he assured, near the new premises of TTSH at Moulmein Road (completed in 1909), and that preliminary efforts had been made to find a site for it. 7

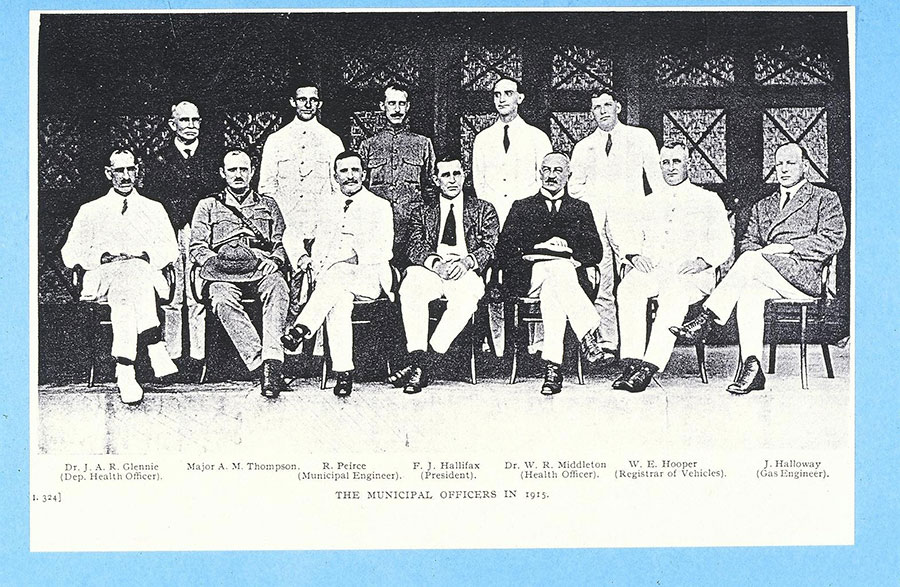

The hospital proposal contributed to the passing of Municipal Ordinance XXXVII in 1907 by the colonial government. The amendments contained major changes which expanded the work of the municipal commission, including ‘to pass By-Laws…for suppression and prevention of dangerous infectious diseases and segregation of patients suffering from such diseases’. 8 Middleton, a Scot, played an influential role, calling for infectious diseases control to draw upon the provisions of the Public Health (Scotland) Act. Broadly, the commission would be responsible for the entire town: to detect overcrowding, demolish insanitary houses, provide back lanes and open spaces, and rebuild unhealthy areas. It hailed the changes as ‘practically an adaptation of the Home Act for the housing of the working classes’. 9

A Litany of Protests over the Site

But while the hospital helped enlarge the role of the municipal commission, its location sparked further conflict. The government had found a preliminary site, naturally enough, at Moulmein Road close to the TTSH in 1905, and the Legislative Council had voted for a contribution of $31,200 for its construction. The full cost would be jointly borne by the government and commission.

This was the extent of the agreement. The following year, the new Governor John Anderson deemed the hospital plan to be ‘too elaborate and the cost excessive’. 10 Some municipal commissioners were also fearful of the possible spread of smallpox to the TTSH and residential houses nearby. They decided to defer the matter to W.J. Simpson, a sanitary expert from Britain whom Anderson had invited that year to investigate Singapore’s high death rates in the town. 11 Simpson felt that the 13-acre Moulmein Road site was too small to manage an epidemic.

The commissioners turned to alternative sites. One was at Paya Lebar, near the Tramway terminus at Serangoon outside the municipal area. But the government and commission were quickly inundated by protests from landowners and residents. The editor of Singapore Free Press submitted a litany of reasons why there was ‘no greater calamity’ than the Paya Lebar site: it was far from town and close to a growing village community and the Recreation Hotel, it would be expensive to acquire the land and would drive down land prices, and infection may be spread by mosquitos and flies. 12 A letter to the paper by ‘Paya Lebarite’, apparently a resident, concurred on the resulting unpopularity of the area, and the need for expensive water piping from the 3rd Mile Stone. 13

The Paya Lebar idea was dropped but subsequent proposals met similar fates. An alternative site at Trafalgar in the northeast of Singapore was judged to be too far from town and lacking a reliable water supply. The most promising location appeared to be near Hood Eng Estate off Telok Blangah Road at Pasir Panjang, owned by the Tanjong Pagar Dock Company. The municipal commission and company were locked in futile talks for three months. Although owned by the government, the company submitted various ‘contradictory’ reasons against the proposal, including the site being earmarked for other purposes (including reclamation) and the ubiquitous fear of the spread of infection. 14

The commissioners, left with no other recourse, returned to the Moulmein Road site. Middleton and R. Pierce, the municipal engineer, found a solution by adding more land, which nearly doubled the site to 25 acres. But this did not bring an end to the matter. In 1910, the municipality revealed that the original scheme had been ‘condemned as extravagant by the Government and a curtailed scheme proposed instead’. 15 After nearly a decade, it lamented, the hospital project was ‘still hanging fire’ – akin to a flintlock musket’s failure to ignite. 16 On 16 September, the commission unanimously stood its ground to reject further proposed cuts to the budget by the government, which finally agreed to contribute half the cost. This institution acceptable to both parties, it was declared, would overcome social stigma towards the existing hospital at Balestier Road; it would be amendable to both sexes and all patients regardless of ethnicity and class. Finally, in 1911, construction of the hospital commenced.

In the same year, however, the largely well-to-do Chetty community submitted a proposal for a hospital of their own, to be built at Paya Lebar. The question of class and ethnicity was still alive and at the forefront of colonial governance. The municipal commission denied the request but only because it did not want separate hospitals. The matter was deliberated by a commission deliberating on amendments to the Quarantine and Prevention of Disease Ordinance. It considered the commonplace objections of upper class Asians to being warded with coolies to be reasonable, and it was not opposed to superior wards for certain groups of patients within the new hospital.

The municipal commission accepted these recommendations in principle. On the surface, the hospital would only have Class B and lower wards for working class Asian patients with cholera and plague. However, European and upper class Asian patients with these diseases could still receive superior accommodation by being admitted to the hospital’s observation wards. For smallpox patients, the commission made concessions for a trio of wards – European, Class A and Class B – the last two being for Asians. The hospital’s planners looked to accommodate, rather than reform, prevailing class and racial sentiments in colonial Singapore.

The Moulmein Road Hospital

On 1 May 1913, the colonial government announced the opening of a new ‘Infectious Diseases Hospital’ at Moulmein Road. 17 Designed mainly by the municipal architect W. Campbell Oman, it was administered by the municipal commission. Its complement of 172 beds comprised three sections for each of the notifiable infectious diseases: smallpox, bubonic plague and cholera. Apologetically, the government stated that only the smallpox section had been built as planned, with separate wards for Europeans, upper and lower class Asians. The push for economy meant that the cholera and plague sections had only lower class Asian wards, but Europeans and upper class Asians could choose to be treated in the observation wards. The Straits Times was more forthright, stating, ‘The new Isolation Hospital in Moulmein Road is little more than the bones of what was proposed when the necessity for a modern institution of the kind was mooted’. 18 The ‘long obsolete’ Quarantine Camp at Balestier Road was closed down and abolished. 19

The new hospital did not yet have a name and was simply known as the Moulmein Road Hospital. It cost over $331,000 to build; the colonial government, contributing a third of the cost, had finally resolved the protracted tussle with the municipal commission over the responsibility for infectious diseases. The hospital’s first medical superintendent was Dr W. Mayne Hitchins, the second assistant municipal health officer, who was assisted by Mrs Toft, the matron. The government gave the commission TTSH’s disused cemetery as the burial ground for the hospital’s deceased. The hospital’s morgue performed autopsies on suspected cases of infectious disease that had previously been carried out at TTSH.

The government hailed the Moulmein Road Hospital as a ‘great advance’ in infectious disease control, ‘properly equipped’ and acceptable to the entire community. Asian patients were reportedly being brought there by relatives and friends, while there were no escapes from the institution in its first year. 20 Subsequent events, however, showed that such self-praise was premature. The following year, when Singapore suffered a cholera outbreak, the admissions were again mostly males. Accommodation quickly became inadequate and in 1914 Middleton urged the commission to take steps to expand it.

It soon became clear that the new hospital was not the complete answer for infectious diseases. Inadequate beds remained a problem in the early years, proof that the government had made a mistake in curtailing the original plan. While it had prioritised the three notifiable diseases, the hospital increasingly treated other infectious diseases, such as diphtheria (cases were transferred from GH to the hospital in 1917), chicken pox and puerperal fever (both made notifiable in 1916), cerebrospinal fever (notifiable in 1917), and tuberculosis (notifiable in 1918).

The hospital was overwhelmed by local cases of the deadly global influenza epidemic in 1918 and 1919. More wards followed: one for diphtheria was built in 1919, followed by a second cholera ward two years later and a second plague ward in 1922. The original hospital premises expanded rapidly and continued to do so, made possible by the acquisition of small pieces of adjoining land.

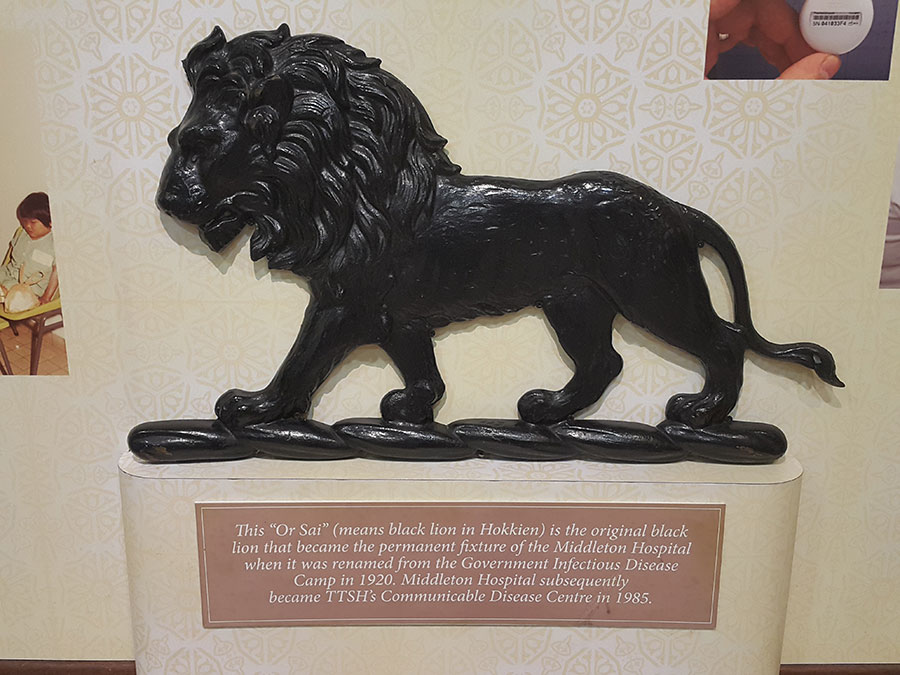

Middleton Hospital and CDC

In 1920, the hospital was finally bestowed the formal name of Middleton Hospital. This fittingly recognised the work and contributions of W.R.C. Middleton, who retired from the municipality that year. As the municipal health officer, Middleton was a tireless advocate for the hospital, and more generally on sanitary matters in Singapore. He passed away later in the year.

The long history of Middleton Hospital will only be mentioned briefly here. Smallpox, plague and cholera became uncommon in Singapore prior to and after World War Two. Diphtheria, a disease of infants and young children, was the most serious illness treated at the hospital, which also treated poliomyelitis, made notifiable in 1941, and typhoid. In the 1930s, the municipal commission, alarmed at the frequency of typhoid outbreaks in the town, attempted to proscribe the numerous itinerant hawkers, especially peddlers of ice-cream and iced drinks.

After the war, Middleton Hospital continued to deal with cases of poliomyelitis, typhoid, cholera, diphtheria, and other infectious diseases. In the 1960s, it screened employees of ice-cream factories for typhoid, showing significant continuity between colonial and post-colonial infectious disease control. In 1960, with the abolition of the City Council (the successor to the municipal commission), the hospital was transferred to the national government.

In 1985, with the discovery of the first Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS) patient in Singapore, Middleton Hospital became the designated institution for the disease. Treatment of this difficult, initially deadly and much stigmatised disease heralded an important phase in the hospital’s history of infectious disease management. In the same year, the hospital was renamed as the Communicable Disease Centre when it was absorbed into TTSH, dropping the name ‘Middleton’ and losing the status of a hospital. Seven years later, with the restructuring of the TTSH, CDC merged with the hospital’s Tuberculosis Control and Epidemiology sections.

CDC continued to manage infectious diseases in Singapore, which remained a major concern due to the city-state’s growing economic and social links with the world. The centre’s most well-known recent contribution was as an isolation centre in conjunction with TTSH during the 2003 Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) outbreak. Like the old infectious diseases, SARS was a challenge with both international and local dimensions.

In December 2018, over a hundred years since its formation, CDC closed. Its historic Moulmein Road site, a sprawling group of terrace wards and pavilions in a zone of greenery, was gazetted for residential development. Infectious disease management passed to the new National Centre for Infectious Diseases nearby in Jalan Tan Tock Seng and part of Health City Novena.

Kah Seng Loh and Li Yang Hsu

Kah Seng Loh is a historian and author of Squatters into Citizens: The 1961 Bukit Ho Swee Fire and the Making of Modern Singapore (NUS Press, 2013). Li Yang Hsu is an infectious diseases physician and head of the Infectious Diseases Programme at the Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health.

This article draws from the research project, ‘Documenting Middleton Hospital, Communicable Disease Centre and the Medical Heritage of Singapore’, which is supported by the Heritage Research Grant of the National Heritage Board, Singapore.

Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia, Issue 26, Trendsetters, November 2019

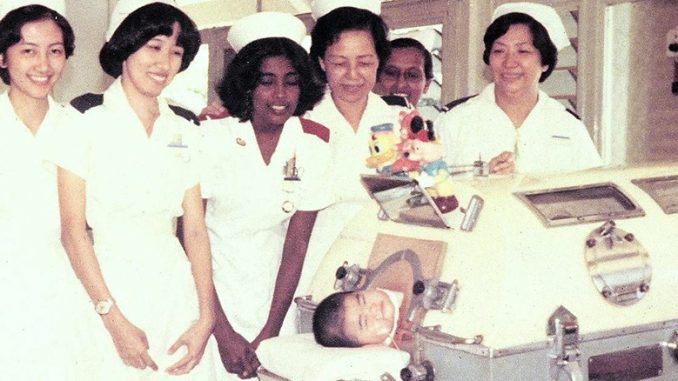

Banner Image: Boy in a negative pressure ventilator (commonly called an ‘iron lung’), celebrating his 1st birthday with nursing staff. Photograph courtesy of Harbhajan Singh.

Notes:

- Singapore Municipality, Administration Report 1899, p. 104 ↩

- Singapore Municipality, Administration Report 1899, p. 105. ↩

- Singapore Municipality, Administration Report 1899, p. 105. ↩

- Singapore Municipality, Administration Report 1899, p. 106. ↩

- Singapore Municipality, Administration Report 1899, p. 106. ↩

- ‘Legislative Council’ 1904, Straits Times, March 12 ↩

- ‘Legislative Council’ 1904, Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, March 12. ↩

- Singapore Municipality, Administration Report 1901, p. 25. ↩

- Singapore Municipality, Administration Report 1907, p. 41. ↩

- Singapore Municipality, Administration Report 1906, p. 9. ↩

- W.J. Simpson, Report of the Sanitary Condition of Singapore (London: Waterlow & Sons, 1907). ↩

- ‘Correspondence’ 1907, Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, June 28. ↩

- ‘Quarantine Camp’ 1907, Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (Weekly), July 4. ↩

- ‘Municipal Commission’ 1907, Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (Weekly), November 7. ↩

- Singapore Municipality, Administration Report 1910, p. 11. ↩

- Singapore Municipality, Administration Report 1910, p. 8. ↩

- CO 275/87 1913 Straits Settlements Medical Report, p. 494. ↩

- Straits Times, 29 May 1913. ↩

- CO 275/87 1913 Straits Settlements Medical Report, p. 494. ↩

- Singapore Municipality, Administration Report 1913, p. 13. ↩