The Internet led to exciting claims and predictions about how it could change the world, one area of which was in terms of democratisation. Academics in the 1990s predicted that with its decentralized, uncontrolled and anonymous nature, the Internet would help liberate people living under autocratic regimes. The prospect of the Internet as a liberating tool was hyped during the Arab Spring and the “Green Revolution” when the media reported of the Iranians using Twitter to mobilise protests against dictatorship.

Recently, James Curran, Natalie Fenton and Des Freedman from Goldsmiths, University of London, debunked several myths about the Internet in the book Misunderstanding the Internet (Curran et al., 2012). One of the myths which was declared unsound is the democratising power of the Internet. Curran et. al. argue that the proclaimed nature of the Internet as being uncontrollable is untrue; autocratic regimes know how to control the Internet as can be seen in China and Saudi Arabia.

When social media is frequently used in political campaigning, Curran et. al. explain that its primary function is expressive, rather than “recasting or regenerating the structures that uphold” the status quo. This tool for expression does not necessarily lead to democratisation. Real democratisation requires real concrete participation from the people.

Moreover, most of the explanations as to why the Internet fails to generate freedom refer to the social context, which predates the Internet. They, however, go only as far as saying that mobilisation initiated on the Internet needs corresponding offline factors; these offline institutions or systems will be the final factor in determining the success of mobilisation. Curran et al. explain that the Internet merely energises activism, but there are other political factors which are more influential in the revitalization of democracy.

The important presumption on which both sides of the debate base their arguments is that Internet users have a democratic spirit and aspire to see their society more liberal, just and equal. Authoritative regimes on the other hand are the ones who suppress freedom. As Duncan McCargo points out, the discussion about social media and democratisation could be termed as the “censorship paradigm,” which sees “a zero-sum contestation between state power (seeking to suppress information and freedom of expression) and heroic citizens/journalists who aim to push back the censors and open up more space for the debate of sensitive and salient political issues.” 1 It might be hard to imagine Internet users as the ones aspiring for less freedom, less equality, and less democracy, but they do exist and even play important roles in some countries. Cases from a Southeast Asian nation show a serious deficit in the attempts to understand the Internet in this aspect.

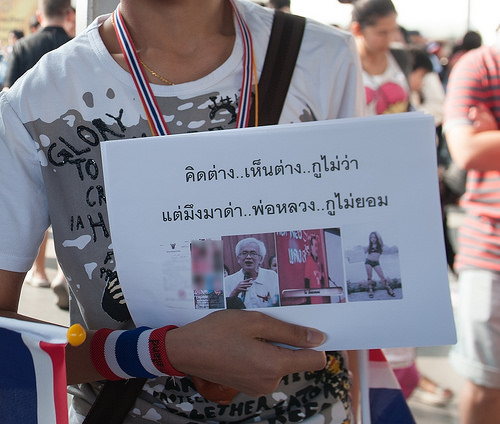

Thailand is a country where democracy has not taken root and whose people are highly polarised. The author has studied cases from 2007-2014 which show that social media functions as anti-social media and is used for illiberal and offensive purposes, and even to promote partisan political stances. The cyberspace of Thailand from 2010-2013 was overwhelmed with what was termed “political cyber bullying”, meaning the posting of personal information and rumor on the Internet in a way that is intended to identify, defame and humiliate the victims because of their political views. Centering on the issue of the monarchy, the practice of political cyberbullying has had serious consequences: one student was denied a place at university; two victims had their employment terminated in Thailand, and; at least six people faced legal charges.

Since the military coup of 19 September 2006, Thailand has been characterised by deeply divided politics. Bangkok has been regularly rocked by mass street protests from either the Yellow Shirt supporters, who mainly are pro-establishment, royalist, and anti-election, and the Red Shirts, who mainly are anti-establishment and supporters of former premier Thaksin Shinawatra. The royalists’ 2008 protests culminated in the closure of Bangkok’s airport and its 2014 protest led to a military coup which toppled the government of Yingluck Shinawatra, sister of Thaksin. Red-Shirt supporters staged mass demonstrations in 2009 and 2010, which were violently suppressed by the then government. The Yellow Shirts have accused Thaksin and the Red Shirts as being an “anti-monarchy movement,” an allegation that the accused cannot counter other than by denying it because the alleged crimes are punishable under Article 112 by up to 15 years in jail. After King Bhumibol Adulyadej endorsed the coup in 2006, Thais have been overwhelmed with hunger for information and eagerness to express their thoughts about the monarchy. This is where new media came in. The Internet provides an uncensored platform for the anti-establishment to discuss the taboo topic of the monarchy when mainstream media dare not to touch the issue (see Kummetha 2012). The first recorded case of political cyberbullying involved users of the progressive, anti-establishment Same Sky web forum, who were bullied in 2007, because of their provocative comments about the monarchy. Chotisak On-Soong, one of the victims, had to move out from his apartment and change his mobile phone number after his personal information was revealed.

The big wave of offensive practices came when the pro-elite government brutally cracked down on the Red-Shirt protesters in central Bangkok in 2010 when than 90 people were killed. Some Red Shirts directed their anger at the monarchy on Facebook and were bullied in return by the pro-establishment side. Vonvipa Kedjulome was reportedly ousted from her job after the royalists launched a bullying campaign against her. The campaign on Facebook urged people not only to harass her through all channels but also to contact her employer and report her ‘disloyal’ behavior. In another case, royalists launched an online bullying campaign against a high-school student using the name ‘Kanthoop’ (joss stick) and pressured universities not to admit her. The campaign went so far as offline royalist protests at a university. She passed the entrance examination to four universities, but three denied her a place due to social pressure (Kummetha, 2014).

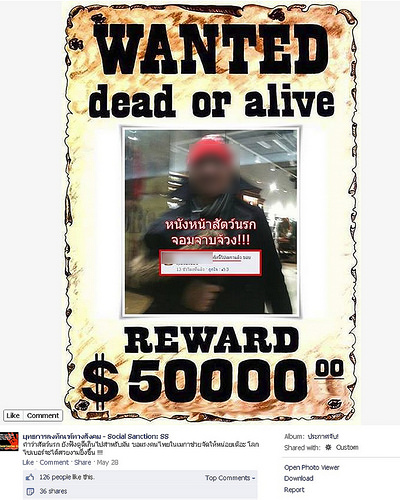

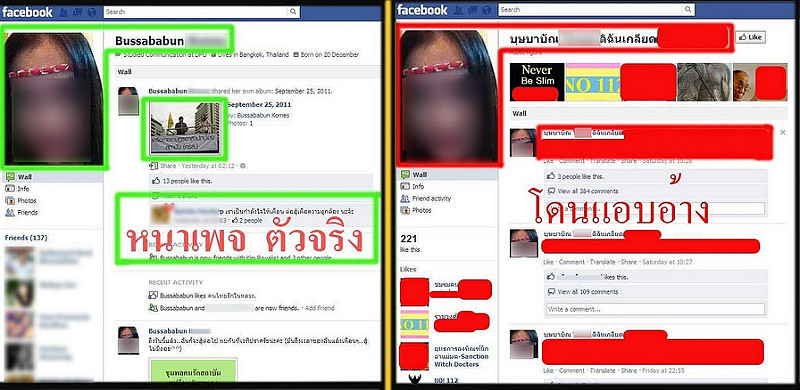

Political cyberbullying in Thailand became more organized and systematic when a group called “Social Sanction” (SS) was founded and operated mainly on Facebook and Youtube around 2010-2013. Proclaiming itself as a private lèse majesté prosecutor, its systematic techniques of political cyber bullying created a climate of fear throughout Thai cyberspace. Since Facebook encouraged the sharing and circulation of what was trending, especially in the form of photos, the SS’s hate speech, degrading comments, and abhorrentlydoctored photos of the victims were widely shared and circulated. An SS co-founder, asked not to be named due to privacy concerns, told the author that by “exposing bad people,” as the SS preferred to call their activities, they helped reinforce the lèse majesté law, which was loosely enforced by the Thai police. Such exposure also brought cases to public attention and led to legal prosecution. Throughout the three years of its existence, the SS bullied more than 50 individuals. Some of the victims were merely Red Shirt supporters and were not involved in lèse majesté (see TNN, 2012).

Subsequently in 2010, anti-establishment groups adopted similar tactics to harass those believed to be guilty of online bullying, for example, by creating spoof Facebook pages/accounts using the names and photos of known right-wing royalists to disseminate messages defaming the monarchy. Later, Anti-Social Sanction was founded by a group of SS victims to uncover the SS members as a means of revenge and deterrence. Surachat Singhaniyom, an Anti-SS core member, told the author that more than 50 Facebook avatars were created to infiltrate the secret SS Facebook group. Due to their more sophisticated tactics, Anti-SS exposed greater amounts of alleged personal information of their victims. For example, names of parents, ID card numbers, and sometimes also the ID card numbers of the victims’ parents were exposed. The SS took revenge by uncovering Nithiwat Wannasiri, a core Anti-SS member, and filed a lèse majesté complaint against him. Due to the legal complaint, the Anti-SS decided to shut down their page (TNN, 2012).

Other tactics to silence criticism against the King include a campaign to manipulate the abuse report system of Facebook and Youtube in order to have the anti-establishment and lèse majesté pages/profiles shut down. A Facebook page called Report Association of Thailand, for example, produced the most thorough and credible graphic manual for this purpose. The page also organized what is called “bomb reports” of target Facebook pages/profiles by multiple users at the same time, ranging from a few hours to a week or a month. This tactic rests upon the assumption that the more reports in a short-time period, the faster a page will be blocked (TNN, 2012).

Even on Change.org, a platform built on the idea of e-democracy, has been used for illegitimate purposes. For example, in 2014 more than 20,000 people signed their names in support of a campaign to pressure the UK government to forcibly extradite a lèse majesté suspect to face prosecution in Thailand (see the petition created by Tubthong: http://chn.ge/1IDtQxW ). Campaigns aimed at censoring differing voices can be found from time to time on Change.org Thailand.

One of the reasons why such anti-democratic uses of social media grow in Thailand is because the right wing feels that Thai civilian governments have not been serious enough in cracking down on dissidents. They use the Internet as the platform to privately prosecute Red Shirts and at the same time pressure the government to follow up cases, and on many occasions, the state authorities have done just that. A survey conducted in 2014 by the author shows that political cyber bullying leads to a climate of fear and self-censorship among Thai Internet users. Most importantly, it shows that the Internet users can themselves be the champions of censorship.

Evidence from Thailand show that anti-democracy and anti-free speech Internet users do exist and discussion about social media and democratisation has overlooked them; an over-simplistic view sees users as stereotypically pro-democracy.

More studies should be conducted in other societies with divisive, on-going conflicts, such as Thailand’s Deep South and Myanmar, where the author has found similar cases. In Myanmar, political cyberbullying tactics were mostly deployed by the anti-Muslim ultra-nationalists during the campaign of ethnic cleansing against Rohingya Muslims in Rakhine State in western Myanmar around mid-2012 to 2013. The targets of online campaigns are not only Muslim Rohingya but also any Muslim from other ethnic groups, Burman human rights defenders, and Burmans who condemn such persecution (Kummetha, 2013).

As can be seen, all qualities which were acclaimed as facilitators of pro-democracy activism also facilitate campaigns with anti-democratic purposes:

Anonymity: Royalists can disguise themselves under pseudonyms and bully the alleged anti-monarchists without accountability or responsibility;

Connectivity: The like-minded right wing get together online and become a strong force against free speech;

Autonomy: Internet users feel that they should take matters into their own hands, rather than wait for slow state mechanisms.

The bullying in the end has the air of e-governance when royalists call on the state for the victims to be prosecuted.

To sum up, the Internet can strengthen activism which has illiberal as well as liberal goals. Yet Internet is content-blind. Its users, however, are the ones who determine its purpose.

Thaweeporn Kummetha

Thaweeporn Kummetha is a Bangkok-based journalist at Prachatai online newspaper and head of Prachatai’s English website ‘Prachatai English’, where she writes mainly on human rights and Thai politics. She is the editor of Thai Netizen Network’s Netizen Report from 2011-2014. In 2013, Thaweeporn was invited to speak at Google Ideas’ forum in New York on political cyberbullying in Thailand and Myanmar.

YAV, Issue 20, Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia. September 2016

References:

Curran, James; Natalie Fenton and Des Freedman (2012). Misunderstanding the Internet. London: Routledge.

Kummetha, T. (2012). “The internet in Thailand: The battle for a transparent and accountable monarchy”. In Global Internet Society Watch 2012 Internet and Corruption. The Association for Progressive Communications.

_____. (2013). “Anti-Social Media? #Cyberpersecution Trending.” Google Ideas. New York.

_____. (2014). “”Witch hunts” at rally sites and on the Internet.” Retrieved from Prachatai English (23 January): http://prachatai.org/english/node/3837

TNN. (2012). “Netizen Report 2011.” Bangkok: Thai Netizen Network.

Notes:

- See the news here: http://www.manager.co.th/iBizchannel/ViewNews.aspx?NewsID=9550000147248 ↩