The fourteenth Malaysian General Election is scheduled to be called on or before 24 August 2018. The election campaigns from both the ruling and opposition parties have virtually started. The clear election agendas so far are the 1MDB and its related scandals and the rising cost of living. Compared to the time when the Wall Street Journal reported the story of Najib Razak’s personal money scandal in July 2015, Najib’s premiership has became more stable after the division of the opposition parties. However, he still faces opposition from the urban middle classes. For scandal-plagued Prime Minister Najib, the announcement of the 2018 budget on 28 October is one of the limited chances to regain some popularity from the urban electorates before the coming General Election.

Najib said his government would place more emphasis on the cost of living and housing issues in the Budget 2018(FMT 2017). Dealing with the problems of housing has been an important political and social agenda since independence. The government has actively supported housing acquisition for low-income groups since the 1970s. However, housing policy under the Najib administration expanded on previous initiatives and added urban middle-income groups. To understand the political economy of housing provision under the Najib administration, we have to look at the history of the Malaysian housing policy.

Brief History of the Malaysian Housing Policy

In the 1950s and 1960s, the scope of the government housing policy was limited; the main target group for housing provision at that time was civil servants. A broader housing policy from the Malaysian government started in earnest in the 1970s. According to Syafiee (2016), the history of housing provision in Malaysia can be divided into four phases, namely ‘Housing the Poor (1971–1985)’, ‘Market Reform (1986–1997)’, ‘Slums Clearance (1998–2011)’, and ‘State Affordable Housing (2012–present)’. Here I follow Syafiee’s categorization to summarize the past housing policy in Malaysia.

The phase of ‘Housing the Poor (1971–1985)’ overlaps the project period of the New Economic Policy (NEP) from 1971 to 1990. NEP had two-pronged objectives, namely eradicating poverty irrespective of race, and restructuring Malaysian society to eliminate the identification of race with economic functions. The introduction of NEP and the steady economic growth since Independence brought a huge inflow of rural residents, mainly Malays into the urban area, especially the Kelang Valley area surrounding Kuala Lumpur. The emerging urban slums in the 1970s prompted the government to address housing for the poor. The government started to impose a rule on private companies where housing project had to have a thirty percent quota of low-cost housing with a controlled selling price of RM25,000 per unit in 1982. During this phase, the main providers of the medium and high-cost houses were private companies, while state governments and their government-owned companies, the State Economic Development Corporations (SEDCs), with the support of the federal government, provided the low-cost houses.

A privatization policy announced by the fifth Prime Minister Mahathir Mohammed in 1983 and the economic recession in 1986 expanded the role of private companies. During the phase of ‘Market Reform (1986–1997)’, private companies played a key role in housing provision. Since the rule of the thirty percent quota for low-cost houses, private companies used the cross-subsidy system, which uses revenues collected by the sale of high-cost houses to reduce the cost of low-cost houses. The federal and state government started to retreat from the direct housing provision during this phase.

However, the government changed housing policy again after the Asian Financial Crisis in 1997. The federal government came to play a leading role in direct housing provision especially for the low-income group by introducing new government schemes like the Program Perumahan Rakyat (PPR) during the phase of ‘Slums Clearance (1998–2011)’. This policy came about following a recommendation by National Economic Action Council (NEAC) to drive economic growth after the crisis and to eliminate slums. To achieve clearance, Selangor state government and KL city hall undertook the ‘Zero-Squatter Policy’ and targeted the year 2005 as the Zero Squatter year (Sufian and Mohamad 2009: 109). The ceiling price for low-cost houses changed from RM25,000 per unit to four pricing tiers, between RM25000 and RM42,000. depending on the location and the type of the house in 1998.

Moving to today, comparing with the three previous phases, the ‘State Affordable Housing (2012–present)’ saw a change in the target group for housing provision. In the previous phases, the government’s main target was those of low-income, and only directly provided low-cost houses in principle. However, both the federal and state governments during the Najib administration started to offer direct housing provision to the middle-income group. Najib announced the new scheme of Perumahan Rakyat 1 Malaysia (PR1MA) in 2011. Under the PR1MA scheme, selling price of houses are between RM100,000 to RM400,000 and the monthly household income of the target group should be between RM2,500 to RM15,000. 1 The house provider, Perbadanan PR1MA Malaysia, is s Federal government-owned company under the purview of the Prime Minister Office. Prices of PR1MA houses are at least 20% cheaper than the prevailing market rates. In addition to PR1MA, various housing schemes targeting for the middle-income group by both Federal and State governments emerged after 2011. For example, the Federal government has schemes such as Perumahan Penjawat Awam 1Malaysia (PPA1M) for civil servants, Rumah Wilayah Persekutuan (RUMAWIP) for the residents in Federal Territories, while the State governments also have their own schemes such as Rumah Selangorku in Selangor and PR1MA Pahang in Pahang.

The involvement of the government in direct housing provision to the middle-income group is an interesting case when compared with neighboring countries. Other than the case of the Housing and Development Board (HDB) in Singapore, the governments of Thailand and Indonesia are not directly involved in housing provision for middle-income groups, although they provide programs for loans, subsidies and tax breaks.

Why did the Malaysian government under the Najib administration start the direct house provision targeted to the middle-income group?

Affordable Housing for the Urban Middle-income Group

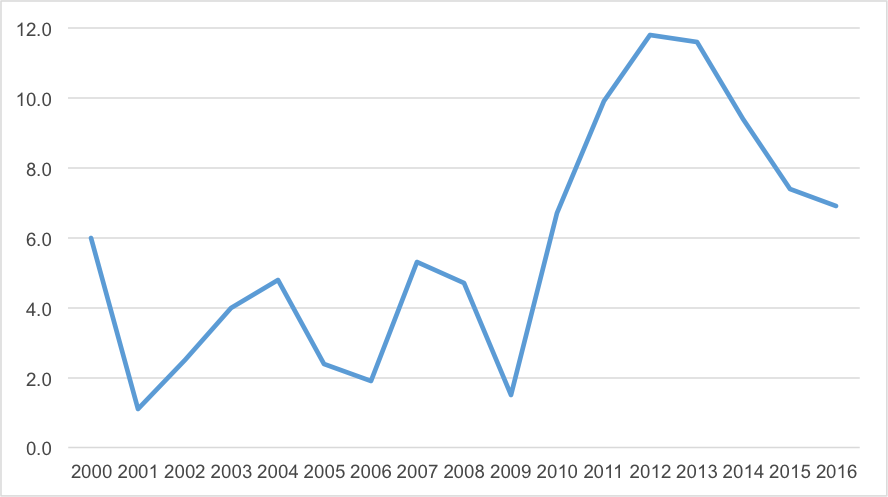

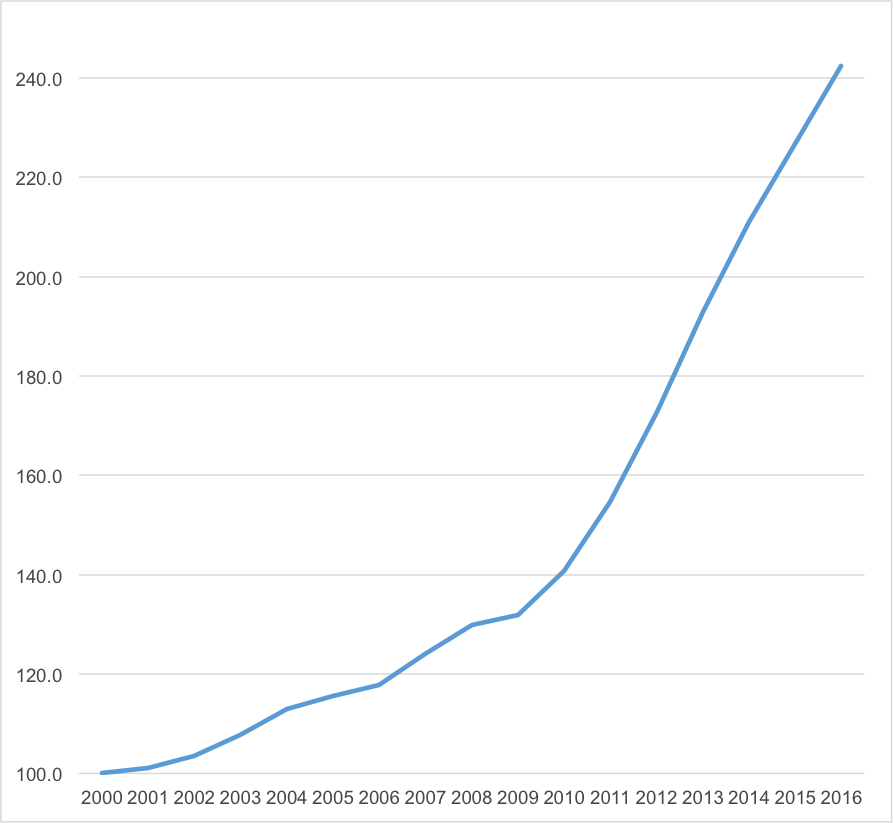

To address the above question, we look at the economic and political background since the turn of the century. Malaysian house prices rose steadily after 2000 as shown on Graph 1. The pace of increase in house prices was temporarily stagnant in 2009 due to the recession caused by the 2008 global financial crisis. However, house price quickly recovered and further increased between 2009 and 2012 as shown on Graph 2.

Source: National Property Information Center (NAPIC)[3]

Source: National Property Information Center (NAPIC)

Property experts and the media warn that Malaysia is facing a potential crisis of a “homeless generation,” where an entire young generation or even generations of prospective house buyers in their 20s and 30s will not be able to buy houses (Lim 2017). Both the demand and supply sides have driven increases in house prices.

On the demand side, demographic factors especially in the urban area make the problem acute. Malaysian population is growing at around 2% per year and will reach 38.6 million by 2040. The urban population rate has increased from 62% in 2000 to 75% in 2016. 2 Median house prices in Kuala Lumpur was 5.4 times the median annual household income in 2014, while the national level was 4.4 times (Khazanah Research Institute 2015: Ⅺ). In addition to the demographic factors, the exemption of Real Property Gain Tax (RPGT) from April 2007 to December 2010 also pushed up house prices. The exemption of RPGT contributed to the mushrooming “property clubs” of speculators and accelerated house flipping for quick profit. The government reintroduced RPGT in January 2010 and increased its rate in January 2013. In November 2011, Bank Negara also reduced the maximum loan-to-value (LTV) ratio to 70% for the third house financing, instead of normally as much as 90% to curb flipping. Rising house prices have contributed high household debt. Malaysia’s national household debt to gross domestic product (GDP) ratio in 2015 stood at 89.1%, with 56.2% of the total debt being loans to buy houses and real estate for residential and non-residential purposes (Malay Mail Online 2016). Concern about household debt incurred by housing loans increasingly moved on to the political and social agenda during the Najib administration.

On the supply side, developer’s continued reliance on traditional construction methods contribute to rising house prices. Using traditional methods, developers take three to four years on average to deliver houses. Long construction periods enable developers to leverage the lack of supply and jack up prices (Syed 2016). Rising abandoned house projects since the Asian Financial Crisis have also badly affected housing costs. Urban Wellbeing, Housing and Local Government Minister Noh Omar said there were 253 abandoned private housing projects in the peninsular between 2009 and July 28 2017 (The Sun 2017).

Wooing Urban Constituents

As rising house prices became a serious economic and social issue for the urban middle-income group, Najib needed to prove that he was addressing this issue properly. He also had a strong political incentive in appealing to the urban middle-income group. In the 2008 General Election, the ruling coalition party, Barisan Nasional (BN) failed to gain the two-thirds majority of Federal Parliamentary seats, a number which it had kept since the formation of BN in the 1970s, instead, it lost four state governments in the west coast of the Peninsular, Selangor, Penang, Kedah and Perak. These losses were largely in urban areas.

Najib announced the Government Transformation Programme (GTP) in 2010, which consisted of seven key areas the government would address. To tackle rising house prices is an important agenda in one of the seven targets, “addressing cost of living” of GST. Before and during the 2013 General Election, both BN and opposition parties promised to deliver affordable housing to woo urban constituents. In the coming General Election, affordable housing will be of yet greater importance to voters.

Tsukasa Iga

Tsukasa Iga is a postdoctoral researcher at the Center for Southeast Asian Studies(CSEAS) at Kyoto University. His main research interests are media, social movements, and political scandals in Malaysia. He also joins the collaborative research project on politics of the urban development in Southeast Asia.

Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia. (Issue 22), Young Academics Voice, December 2017

Free Malaysia Today (FMT). 2017. “PM: Budget 2018 to focus on living cost, housing issues,” September 8 (http://www.freemalaysiatoday.com/category/nation/2017/09/08/pm-budget-2018-to-focus-on-living-cost-housing-issues/).

Khazanah Research Institute. 2015. Making Housing Affordable. Kuala Lumpur: Khazanah Research Institute.

Lim, Ida. 2017. “Warning of ‘homeless generation’, HBA wants Rent-to-Own’ for middle-class too.” Malay Mail Online, April 4 (http://www.themalaymailonline.com/malaysia/article/warning-of-homeless-generation-hba-wants-rent-to-own-for-middle-class-#ugTQjedFcsJrEZx9.97).

Malay Mail Online. 2016. “Malaysia’s household debt to GDP stands at 89.1pc,” April 29. (http://www.themalaymailonline.com/malaysia/article/malaysias-household-debt-to-gdp-stands-at-89.1pc#kweeThFQbkdlposu.99).

Sufian A. and Mohamad N. A. 2009. “Squatters and Affordable Houses in Urban Areas: Law and Policy in Malaysia.” Theoretical and Empirical Research in Urban Management 4(13): 108-124.

Syafiee Shuid. 2016. “The housing provision system in Malaysia.” Habitat International 54: 2010-223.

Syed Jaymal Zahiid. 2016. “How a skewed system keeps house prices high and developers rich.” Malay Mail Online, October 18 (http://www.themalaymailonline.com/malaysia/article/how-a-skewed-system-keeps-house-prices-high-and-developers-rich).

The Sun. 2017. “Govt rehabilitates 190 abandoned private housing projects,” August 2 (http://www.thesundaily.my/news/2017/08/02/govt-rehabilitates-190-abandoned-private-housing-projects).