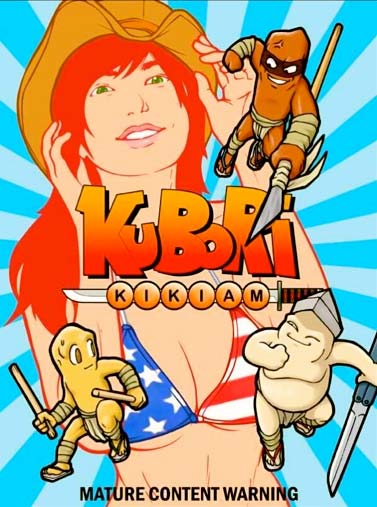

Michael David. Kubori Kikiam: Strips for the Soul Omnibus.

Quezon city: Flipside Publishing, 2013

Reviewed by Kristine Michelle L. Santos

Hence, the generation of children after the end of Bomba comics have idealised perceptions of Philippine comics where righteous heroes line the pages and commit to fulfilling good deeds from one panel to the next. Heroes are not seen crass, rude, or lewd. Nor are they seen small, stupid, and inferior. That said, one of Manila’s most popular independently published comic has the smallest of heroes and one of the most vulgar dialogue in local comics.

So where do we place Michael David’s Kubori Kikiam in Philippine comics?

Kubori Kikiam began in 2000 as a gag comic serial in the local comic magazine Culture Crash. The comic tracked the lives of three mutated kikiams as they thrive to survive the real world and overcome their rivals, shrunken-wielding mutated ninja fish balls. Like fish balls, a kikiam is a processed Chinese meat sausage and is a staple of Philippine street food. Imagining a mutated street food is not far from Philippine reality as locals are fully aware of its dubious and possibly dirty origins. Thus, the three kikiams — Benjo, Manny, and Dodon — are likely small heroes. Together they work as a wonderful comedy trio that matches the energy of the Three Stooges. Benjo portrays the smart collected character, Dodon plays the hot head, while Manny balances the other two characters with his air headedness.

As their struggles surged from one chapter to the next, Kubori Kikiam showed hints of its comedic formula that was buried under heavy censorship. Profanity was heavily bleeped and sexual references were mostly implied or censored altogether. This censorship was a deliberate choice by David as he was fully aware the magazine had a young readership.

[pullquote]Kubori Kikiam screams to talk about sex and sexuality because currently, no one is talking about it[/pullquote]When Culture Crash ended, Kubori Kikiam found freedom on the internet as it reformatted the comic as a comic strip online and an independently published comic. On the web, Kikiam’s three heroes finally had the liberty to say what they had to say under themes that no one could censor them for. The running gags dabbled on Japanese pornography, strip clubs, Facebook, drinking, and casual sex while its characters exhibited lewd behaviour that APEPCOM would have considered offensive. However, unlike the previous Bomba comics, Kubori Kikiam does not have pornographic intention but rather, its purpose is to satire the naïve and childish attitude that young adults have when it comes to sex and sexuality. It screams to talk about sex and sexuality because currently, no one is talking about it.

For all its madness and profanity, Kubori Kikiam is representative of a generation of young Filipino adults who have been deprived of sexual education, repressed of sexual expression, and manipulated to believe that sex is wrong. If anything, Kubori Kikiam shows how little understanding Filipino youth have about sex and how a generation of children approach sex with childish witty banter. It uses the kikiams to express the readers’ childish curiosity and excitement over sex. Its supporting characters serve as informal teachers who guide its audience through various dimensions of sex and sexuality.

More than sex, the crass language of the comic and the unrefined behaviour of some of its main characters also represent a lowbrow comedy representative of Filipinos in the lower classes. Their interests such as excessive drinking, rap groups, strip clubs, and variety talent shows are indicative of the author’s intent to paint a holistic picture of the people present in Philippine society and how anyone is susceptible to the temptations of immoral behaviour.

There is bravery in the creation of Kubori Kikiam as it takes full responsibility for its approach, raising topics and themes that local artists fear to thread. Surprisingly, the highly conservative censors have turned a blind eye towards this comic as it continues to receive critical acclaim and popularity within the youth (Tan 2010; Santiago 2012; “KOMIKON Awards 2009 Winners” 2009). While other artists seek to redefine Philippine comics through various retellings and re-imaginings of Philippine folklore, Kubori Kikiam makes an asinine effort in representing the current generation of Filipino youth who are curious, bashful, offensive, yet vibrant, diverse, and intelligent through its ragtag crew of mutated food.

Kristine Michelle L. Santos

Kristine Michelle L. Santos is PhD Candidate at the School of Humanities and Social Inquiry

Faculty of Arts, Law, and the Humanities

University of Wollongong

Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia. Issue 16 (September 2014) Comics in Southeast Asia: Social and Political Interpretations

References:

“KOMIKON Awards 2009 Winners.” 2009. Philippine Komiks Convention. http://www.komikon.org/komikon-awards-2009-winners/

Marcelino, Ramon R, ed. 1985. A History of Komiks of the Philippines and Other Countries. Manila: Islas Filipinas.

Santiago, Katrina Stuart. 2012. “Book Review: ‘Kubori Kikiam’: Reprieve in Irreverence.” GMA News Online. April 20. http://www.gmanetwork.com/news/story/255561/lifestyle/reviews/book-review-kubori-kikiam-reprieve-in-irreverence.

“Sinasam Ng Pulisya Ang Malalaswang Komiks at Magazines for Men [Police Confiscated Lewd Komiks and Magazines for Men].” 1969. Pogi Magazine for Men, September 18.

Tan, Budjette. 2010. “Required Reading : 25 Pinoy Comic Books.” Inquirer.net. April 12. http://lifestyle.inquirer.net/super/super/view/20101204-306877/Required-reading–25-Pinoy-Comic-books.