Educating in Uncertain Times

The pandemic kept people contained in homes, unsettled students’ lives, and ratcheted up online education worldwide. Helping students adjust to their new virtual classroom set up, lowering their anxieties, and keeping them engaged in the learning outcomes of their courses figured prominently among teacher concerns in Japan. This article seeks to highlight the authors’ proactive approach toward shifting our focus away from “delivering online content” toward having students diagnose problems and proffer creative solutions. In doing so, we were purposeful in seeking to ignite our students’ imaginations, build a sense of community, and raise awareness about the fears and anxieties brought about by the pandemic in sociological fashion. We were initially uncertain of the result, but we were conscious of our responsibility to inspire students, to help them make sense of their experiences in a broader context, and to engage their hearts and minds in our curricular design. Our approach to teaching sociology during the pandemic emphasized: fostering students’ aspirations, nurturing reflexivity and awareness, and finally, practicing empathy through communication. Online education during a pandemic creates more distance, yes, but also the potential for more connection and safety because of that distance. We used the COVID disruption, to not only test virtual content delivery, but most importantly, to shift our attention toward connecting students to themselves and to one another.

Student Vision Boards – Allen Kim

In the college classroom, asking students – “What do you want from life?” – is not part of a regular dialogue that happens between students and faculty. It is unfortunate because few students often have clarity about what they want from their future upon graduation. Prompted by these concerns, in a course titled “Education and Work in Society,” I designed an assignment requiring students to create their own vision board. A vision board or dream board is a collage of images, pictures, and affirmations of one’s dreams and desires, designed to serve as a source of inspiration and motivation (Rider 2017). The purpose of the student vision board assignment was twofold. Firstly, I wanted to provide students the creative opportunity to imagine and visualize what meaningful work looks like in the context of their lives. Work occupies the majority of a person’s life while intimately connected to family, health, and one’s self worth and identity. Secondly, I was concerned about students largely confined to their homes, experiencing anxiety, and in some cases loneliness. I sympathized with freshman students unable to visit campus, make new friends, and for whom my “Zoom” course was their first college experience. Therefore, an activity linking purpose, meaning, and connection with others, seemed appropriate for the times.

Toward this end, students were tasked to create a poster in digital or physical format based on their dreams. This included a poster replete with images, ideas, and quotes, representing what they wanted out of life. I provided links explaining how to create vision boards along with examples of people’s designs. Students were also assigned readings on the science of success from biology, psychology, sociology, economics, and demography. While hard work and innate talent matter, students learned how mindset, exercise, grit, family, money management, and work life balance, are also part of the success equation (Time 2019). Motivated by this research, students embarked on the creation of their personal vision boards. Students were required to give a presentation explaining their vision boards to the class. Classmates in turn asked questions regarding the presenters’ hobbies, interests, career interests. In one vision board presentation by a freshman named Riko, classmates took notice of her corkboard and use of pins to add, remove, or easily modify images on her board over time. She expressed her love of horses and nature and emphasized the importance of personal wellbeing through healthy food, community service, and social networking. Students complimented Riko on her use of floral themes, and the natural warmth and beauty emanating from her poster (see image below). Her career goal was to work for an international organization focusing on sustainability. Importantly, she elected to include a picture of her most recent achievement entering a university. It was important for her to recognize the milestones that she achieved in her life.

Numerous positive outcomes came from the vision board assignment. The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the need for connection, meaning, and normalcy for students worldwide. One student shared their fascination, “looking inside the head of their fellow classmates” and being energized by their unique personalities. It became evident that students desperately wanted to share their lives, learn about the dreams of their peers, and focus on their futures. From a ramen shop, RC car circuit, and academic institute owner, to lawyer, and PhD student, the passion and energy emanating from students was manifest. Students from the course even decided to have a reunion the following term to build upon their newly developed friendships. Following the course, Riko posted her vision board on Instagram, which garnered great interest and enthusiasm from her friends. As an educator, I was unaware how meaningful a vision board assignment could be for students individually and collectively. While students may have thought about their futures, they may have never written it down in a notebook, let alone in the form of a visual poster. In the end, the most powerful outcome of the activity was that students took time to stop and marvel at themselves, and one another’s infinite potential as human beings.

Globalization, the Self, and COVID-19 – Johanna Zulueta

In the beginning weeks of my Sociology of Globalization class, I facilitated a workshop titled: “Globalization and the Self: Globalization in the Time of a Pandemic.” I told students to reflect on their everyday lives during the pandemic by encouraging them to think about changes in their everyday practices, interpersonal relationships, their emotions, as well as relating their experiences with events in their communities and in the world. I asked them to write their reflections individually followed by sharing time with their group mates. The purpose of this activity was to connect student experiences to globalization, thus helping them understand how large scale issues may be understood at the micro-level. Students shared how their everyday lives drastically changed in the midst of the pandemic. For example, many of them spoke about how their sleep patterns were altered, how they felt closer to their parents as a result of spending more time at home, and how they utilized food delivery services. Students mentioned time saved from not needing to commute to school every day. On a negative note, the state of emergency and calls for “self-restraint” kept them physically isolated from their friends and schoolmates. Some students shared:

“I realized I am relatively fortunate because some other university students have to live all by themselves. I got to stay home with my family and financially depend on my parents, which allows me to feel secure for now.”

“I got much time for spending myself [sic], so I have many opportunities to invest [sic] myself by reading books, finding new hobbies, and obtaining good habits. The classes of the university are all online, so I do not need to commute which I used to travel for two hours one way.”

The above quotes illustrate the unintended consequences of shifting to online classes. There were surprises, both positive and negative. Students were not alone in their experiences and this shared reality enhanced their emotional connection to their peers.

Through Zoom, I created opportunities for student interaction to reflect upon diverse aspects of globalization. Unlike in-person classes where students are co-present spatially and temporally, online synchronous sessions only allow for temporal co-presence. The “Globalization and the Self” activity built connections among students and made them aware of how their peers were dealing with personal transformations during COVID-19 such as isolation and greater intimacy. These observations further nurtured reflexivity and collective awareness among students. In this way, for students, the notion of globalization is no longer a remote idea; as it has become “in here,” in our consciousness (Giddens 1994: 95; Cohen and Kennedy 2013: 46). Students were able to exercise the concept of “globality,” or the “consciousness of the world as a single space” (Robertson 1992: 132) that introduced them to the “subjective” realm of globalization. They provided positive feedback sharing that the contents of the course is “highly related to their lives” and that they felt a sense of “familiarity” with the things discussed in class.

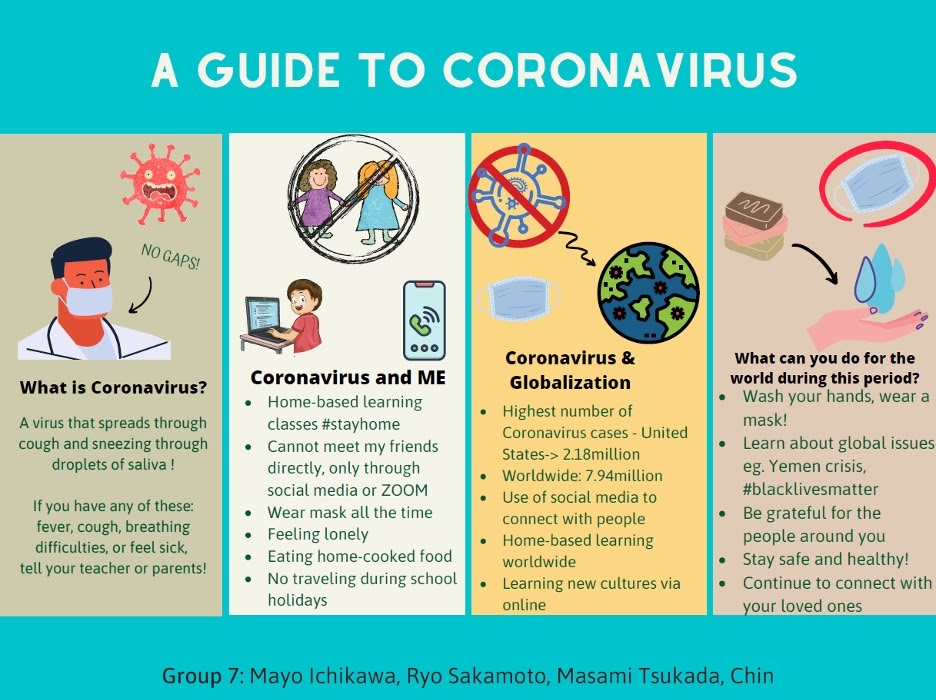

Additionally, I encouraged students to take on the role of a “teacher” by educating their younger peers about the concepts and theories covered in our globalization course. This culminated in a project where students in groups of four created posters relating globalization and COVID-19 for an audience of children aged 9 to 12. Apart from sharing knowledge, this activity enabled students to tap into their creativity and be connected to their classmates by brainstorming and working as a team.

Through the Globalization and COVID-19 project, students felt more connected to each other as a result of working on a meaningful project, engaging peers on the social problems stemming from the pandemic, and being solution-oriented by coming up with ways to cope with various socio-cultural changes accompanying this “new normal”. They were also able to engage their hearts and minds with the topic, as they felt more inspired in their learning.

A Classroom to Remember

As sociology professors our formal training prepared us to be academics. Facts, figures, and connecting ideas is the basis of our work as intellectuals. However, following the first wave of the pandemic, we became aware that students and teachers yearned for connection. We realized the importance of connecting people, not just ideas. Our activities involved self-discovery, self-disclosure, and sharing with classmates and family members. For the Work in Society course, vision boards demonstrated how dreams are filtered through a matrix of culturally inherited qualities, family influences, and other personal life experiences. Every element on their poster was a window in students’ worldview and unique personality, and discussions about the nature of work, life, and society. For the Globalization class, workshops and group projects provided opportunities for student interaction, leadership and reflexivity. These creative and experiential activities generated student engagement we thought not possible in the online environment.

It was difficult to know what the pedagogic, emotional, and relational outcome would be for our courses. Our teaching is a work in progress, but we felt strongly about an education that makes a difference in the lives of our students, and empowers them with the confidence, knowledge, and empathy to contribute to their classroom and communities. At a time when the world is facing serious concerns, universities play an important role toward advancing sustainability and the SDGs (Purcell, Henriksen, and Spengler 2019) in a rapidly changing world. If we are going to rebuild our societies, students must be adept, curious and knowledgeable about their environment, but also in developing profoundly human skills such as social and emotional intelligence, empathy, teamwork, and cooperation. Pandemic pedagogy, therefore, requires the need for more caring academics and meaningful assignments by which we can share experiences, ideas and build a shared understanding among diverse students.

Allen J. Kim and Johanna O. Zulueta

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank Riko Kimura, Mayo Ichikawa, Ryo Sakamoto, Masami Tsukada, and Toh Jian Qun for letting us use their poster for this article.

Johanna O. Zulueta is Associate Professor of Sociology at the Faculty of International Liberal Arts of Soka University. She received her B.A. (Social Sciences) from the Ateneo de Manila University and her Ph.D. (Sociology) from Hitotsubashi University as a Monbukagakusho scholar. Her research interests focus on migrations in East Asia, particularly on issues related to ethnicities, gender and families, citizenship, return and home, and ageing. Currently, she is examining perceptions on ageing and the end-of-life, as well as social well-being among older Filipino women in Japan. In addition to peer-reviewed articles, she also edited books about migrations between Japan and the Philippines. Her recent book is titled: Transnational Identities on Okinawa’s Military Bases: Invisible Armies (Palgrave Macmillan, 2020).

Allen J. Kim is Associate Professor of Sociology at International Christian University in Tokyo, Japan. He received his B.A. from the University of California Berkeley (Ethnic Studies and East Asian Studies) and his Ph.D. (Sociology) from the University of California Irvine. Following his management career in the telecommunications industry in the Silicon Valley, he pursued a Fulbright ETA program in South Korea before pursuing academia. His research interests men in families, migration, ethnicity, men’s movements, work, leadership development and entrepreneurship.

References:

Cohen, R. and Kennedy, P. (2013). Global Sociology, 3rd Edition. Hampshire, Palgrave Macmillan.

Giddens, A. (1994). Living in a Post-Traditional Society. In Beck, U., Giddens, A.,& Lash, S. (Eds.) Reflexive Modernization: Politics, Tradition, and Aesthetics in the Modern Social Order. Cambridge: Polity.

Purcell, W. M., Henriksen, H., and Spengler, J. D. (2019). Universities as the Engine of Transformational Sustainability Toward Delivering the Sustainable Development Goals: “Living Labs” for Sustainability. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 20(8): 1343-1357.

Rider, E. (2017). The Reason Vision Boards Work and How to Make One. Huffington Post. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/the-scientific-reason-why_b_6392274

Robertson, R. (1992). Globalization: Social Theory and Global Culture. London: Sage.

Time Special Edition – The Science of Success. (2019).