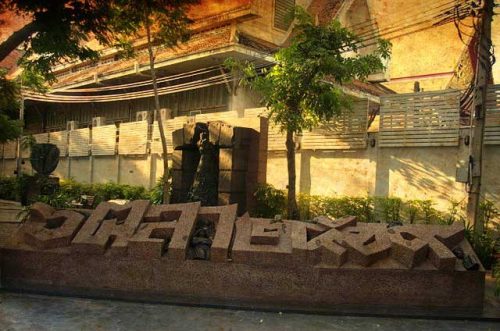

This morning I went to pay my respects to the heroes of 14 October and 6 October…

Every week or two, I buy two flower garlands and go to pay my respects in front of the main Auditorium of Thammasat University at the memorial to the popular uprising against dictatorship on 14 October 1973 and to the massacre of students on 6 October 1976.

I slip one garland on a hand of the statue of the heroes of 14 October, then join my hands, bow my head, and think of “rights and freedoms.”

I place the other garland in the middle of the marble plinth memorializing the heroes of 6 October, then join my hands, bow my head, and think of “social justice.”

For sure, thirty years ago the words “social justice” were interpreted as equivalent to “socialism.” Following the political crisis of the Thai revolutionary movement under the leadership of the Communist Party of Thailand, and the international crisis of socialist ideology over the subsequent two decades, this interpretation has gradually vanished. Even so, the dream of social justice lives on.

For Octobrists of my generation, the two ideologies represented by the historic movements of 14 October 1973 and 6 October 1976 are different, but at the same time they are related. In one sense, without rights and freedoms it is impossible to fight for social justice. And conversely, without social justice rights and freedoms can have no meaning, at least no meaning for society, no meaning for us as fellow countrymen, human beings, or citizens of the world. Though it may have meaning for us as individuals, that is not enough.

The materialization of this difference-but-relatedness of these two ideologies was the triple alliance [workers+peasants+students and intellectuals] which emerged in the context of the peaceful struggle in the city during the three years of open democracy following 14 October 1973, and which flourished during the armed struggle in the countryside after the coup of 6 October 1976 brought the return of dictatorship.

I’d like to propose that this ideology of 14 and 6 October—or, for simplicity, the Octobrist ideology—of [rights and freedoms + social justice] has now disintegrated. And the chief reason why it has disintegrated is the fragmentation of the people’s movement in Thailand in the context of the political conflict over the Thaksin government during the past year.

It took over thirty years for the Octobrist ideology to weaken, yet now it seems to have withered and died.

This fact is plainly visible in the conflict among the Octobrist friends and colleagues who have splintered, factionalized, and fallen into mutual recrimination and total confusion.

On one side there are Dr Phrommin Lertsuridet, Phumtham Wechayachai, Chaturon Chaisaeng, Sutham Saengprathum, Phinit Jarusombat, Adisorn Piangket, Kriangkamon Laohapairot, Phichit Likhitkijsombun, and so on.

On the other are Thirayuth Boonmee, Phipob Thongchai, Prasarn Mareukphitak, Dr Weng Tochirakan, Chermsak Pinthong, Kaewsan Athipo, Chaiwat Surawichai, Khamnun Sitthisaman, Yuk Sri-arya, Suwinai Pornavalai, and so on.

These two sides disagreed fierily and furiously over the Thaksin government, over the call for royal appointment of a prime minister under clause 7 of the 1997 constitution, over the king’s call for judicial intervention, and over the coup of 19 September 2006. And their conflict spread to the activist intellectuals of subsequent generations such as those of May 1992, and those in the political reform and people’s politics movements of 1997.

This conflict reached such ferocity that websites belonging to Octobrist colleagues and former jungle comrades censored the words of Thongchai Winichakul posted from the University of Wisconsin, and the executive committee of Club 19 of the former comrades in the lower northeast were so severely criticized by fellow members for showing a political stance somewhat close to the Thaksin government that the whole board resigned to make way for a new election.

However, the real evidence for the disintegration of the Octobrist ideology lies in the clear-cut split since the start of the year between middle-class civil society movements demanding political and economic rights and freedoms on the one hand, and grassroots people’s movements in city and countryside calling for social and economic justice on the other. The former oppose the Thaksin government as the political agent of the big capitalist class and ally themselves with the traditional elite to drive the government out while the latter supports and defends the Thaksin government.

History is playing a very bad joke when on the one hand the middle class pins its hopes on the elite of army-bureaucracy-technocracy, known in the old Octobrist language as the “warlords and feudal lords,” to protect their rights and freedoms, while on the other hand the lower-class grassroots masses pin their hopes on a government of big monopoly capitalists to provide them with justice.

Rarely do we see such a convoluted double false consciousness in one and the same polity!

For evidence how far the latter have got lost, we need look no further than the Thaksin government’s neoliberal economic policies such as privatization of state enterprises, liberalization of the private sector, and free trade agreements, along with conflict-of-interest and various kinds of policy corruption such as the sale of Shin Corp to Temasek Holdings of Singapore.

And for evidence how far the former have got lost, we need look only at the announcements by the coup junta, especially the provisional constitution of 2006.

But such things have their reasons. Surely the middle class people pin their hopes for rights and freedoms on the elite of army and feudal aristocracy, rather than on the big capitalist class, precisely because of the authoritarianism-absolutism-autocracy of the big capitalist government which overrode and undermined the rule of law, constitution, and rights and freedoms of the citizenry on a massive scale and in a totally brazen fashion for the past five years? Ultimately the big capitalist government goaded the very middle class groups that should have been the foundations of its own government to ally themselves with the warlords and feudal lords.

In sum, Thaksin’s failed leadership as prime minister and head of the Thai Rak Thai party has driven Thailand’s bourgeois revolution backwards by about ten years!

Conversely, surely the grassroots masses pin their hopes for social and economic justice on the big monopoly capitalist class precisely because the alternative of community/sufficiency economy is too difficult, burdensome, and slow, demanding determination, sacrifice, forbearance, and the discipline of delayed gratification—in short, not as immediate or inspiring as the alternative of capitalist+consumerist populism offered by the big capitalist government? Ultimately the grassroots mass, which once was the base on which the elite of warlords and feudal lords defeated the biggest-ever challenge their government ever faced in the people’s war with communism twenty years ago, has been transformed into the broad electoral base and solid popular support for the big capitalist party.

In sum, the fact that the grassroots mass mostly prefers the policies of capitalist+consumerist populism scattered about by the big capitalist government reflects the limited appeal of the anti-mainstream movement of community/sufficiency economy.

The quest for rights and freedoms from the warlords and feudal lords, and the quest for justice from the monopoly capitalists, will both turn out to be dead ends.

The mistakes and mutual recriminations among former comrades in ideology and political action can go on reproducing themselves endlessly over various minutiae of the same Octobrist ideology.

Neither side’s criticisms are totally wrong. But neither side is totally correct either (for sure, including this writer). That is because the constraint facing us all is the limited nature of political forces and political alternatives in Thai society in general. This constraint affects both the traditional ruling class and the new monopoly capitalist class, both the middle class civil society movements and the lower class mass grassroots networks as well.

And this constraint has splintered the Octobrist ideology right down to its roots to a point it is difficult to see any way it can ever revive and reunite in the future.

Kasian Tejapira

Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia Issue 8 (March 2007)

Originally published in Matichon Daily, 20 October 2006, p. 6.