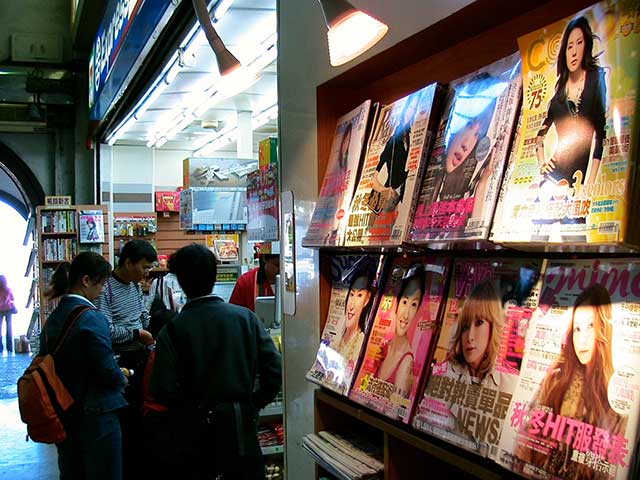

Over the last two decades, Japanese popular culture products have been massively exported, marketed, and consumed throughout East and Southeast Asia. A wide variety of these products are especially accessible and readily apparent in the region’s big cities. Many Hong Kong fashion journals, for example, are Japanese, in either original or Cantonese versions. Japanese comic books are routinely translated into the local languages of South Korea, Thailand, Indonesia, and Taiwan, and they dominate East Asia’s comic book market. The Japanese animated characters Hello Kitty, Ampan Man, and Poke’mon are ubiquitous, depicted on licensed and unlicensed toys and stationary items in the markets of any typical Asian city. Japanese animation, usually dubbed, is the most popular in its field. Astro Boy, Sailor Moon, and Lupin are successful examples of animated characters seen in almost every shop that sells animé in Hong Kong and Singapore. In China’s big cities, too, now that hedonism is politically acceptable, Japanese popular culture products quickly fill local stores, opening doors into the country’s expanding cultural market.

The success of Japanese popular culture in East and Southeast Asia during the last two decades has occasioned a flood of academic writing. Although the topic is still relatively neglected in political science and international relations literature, it is staple fare in cultural studies, anthropology, and ethnography. The majority of works have focused on particular examples, emphasizing the reaction of audiences to cultural exposure in relation to the global-local discourse (Alison 2000; Craig 2000; Ishii 2001; Iwabuchi 2004; Martinez 1998; Mori 2004; Otake and Hosokawa 1998; Treat 1996). No single study has so far provided comprehensive empirical evidence regarding the capacity of the newly created Japanese cultural markets in East and Southeast Asia, nor examined these issues within a regional paradigm.

It is not possible to analyze here the plethora of studies on the dissemination of Japanese popular culture and all the insights they provide, nor is the author competent to do so. This article instead addresses some of their major theoretical and analytical foci, all of which touch directly on the central problem of analyzing Japan’s cultural expansion overseas. Its main purpose is to propose a regional paradigm for analyzing the dissemination of culture throughout East and Southeast Asia, including Japanese popular culture.

The Existing Literature: Everything is Global

Most studies of Japanese popular culture abroad consist of a series of anecdotal case studies with a strong tendency to privilege the text and its representational practices. This is partly understandable, owing to the specific interest of the academic discipline and given the lack of comprehensive empirical information on the subject. Timothy J. Craig’s edited volume, Japan Pop! Inside the World of Japanese Popular Culture (2000), is a good example. The book discusses the phenomenal success of Japanese popular culture in the 1990s. Its first thirteen articles include textual analysis of Japanese music, comics, animation, television programs, and films, while the last four articles discuss the dissemination of Japanese comics, animation, and pop idols abroad.

Other notable examples are the edited volumes of John Lent, Asian Popular Culture (1995), and of Timothy J. Craig and Richard King, Global Goes Local: Popular Culture in Asia (2002). These books include analyses of specific Japanese popular culture products and fields, examining their contextual narrative, practice, and broader social meaning. In Asian Popular Culture, for example, Ron Tanner looks at the making of animated toys, their export to the United States, and the way these toys reflect “the [Japanese] nation’s inclinations, if not the agenda of the government” in the hope for a brighter future (100). In the same volume, Ito Kinko inquires about the meaning of weekly comic magazines in Japan, arguing that “comic magazines do reflect social reality in terms of the occupations and roles of woman, gender power structure, and double standards” (134). Similarly, in Global Goes Local, Mark MacWilliams argues that Osamu Tezuka’s famous comic Hi no tori (The Phoenix) implicitly “revisions Japanese religiosity.” There are many other published examples of these trends. Prominent works include Martinez 1998; Mori 2004; Otake and Hosokawa 1998; Schodt 1996; and Treat 1996.

In explaining the success of Japanese popular culture in East and Southeast Asia (but not in America or Europe), some suggest that “cultural proximity” determines the trajectory of cultural flows. They maintain that Japanese popular culture embodies some sort of Asian content, or “Asian fragrance,” which easily resonates with local consumers. According to this view, cultural confluence is geo-cultural and not simply transnational. Writing about Japanese TV dramas in East and Southeast Asia, Iwao Sumiko has introduced the concept of “shared sensibilities” (1994: 74), Honda Shino the “East Asian psyche” (1994: 76), and Igarashi Akio “cultural sensibility” (1997: 11). This “cultural proximity”, however, cannot explain why Taiwanese youth, for example, prefer to buy Japanese instead of Chinese products, or why Thai students listen to American music, which is ostensibly not as “culturally” close.

Others have argued that Japanese popular culture products are “faceless” (see Alison 2000; Shiraishi 2000). That is, the appeal of Japanese popular culture derives from being non-national and therefore highly transferable, to the extent that it is no longer recognized as “Japanese.” Indeed, it is difficult to see what is “Japanese” about the animated characters Hello Kitty, Doraemon, or Poke’mon, or how any sort of subliminal cultural messages that may be embedded in the products resonate with Asian consumers.

On the other hand, consumers in East and Southeast Asia do seem able to recognize cultural products that originated in Japan. In conducting a series of interpretative questionnaire surveys with 239 university students in Hong Kong, Bangkok, and Seoul, 1 one of my strongest impressions was that most could identify Japanese animation, music, and comics, even when they were translated into local languages. They could also distinguish among Japanese popular culture products, other imported products, and local imitations. In this sense, the “Japanese odor” of the products might lay in their representation of a specific genre associated with “Japan” that is recognizable and appreciated by consumers, rather than in their containing an “Asian” cultural fragrance.

The work of Iwabuchi Koichi (2002; 2004) offers another approach, one that interprets the manifestation of “Japanese” cultural practices within a broader cultural dynamics. Iwabuchi is a pioneer in the study of Japanese popular culture in East Asia and Southeast Asia, and his works provide rich evidence of the popularity of Japanese television dramas in Taiwan, Hong Kong, Bangkok, South Korea, and mainland China. He maintains that the concept of “cultural proximity” does not necessarily explain the consumption of Japanese popular culture. Rather, he argues that Japanese popular culture products represent “modern” ideas that consumers strategically choose.

In his book Recentering Globalization (2002), Iwabuchi situates the rise of Japanese cultural power in light of the globalization process. His central argument is that the expansion of Japanese culture to Asia in the 1990s correlates with the decentralizing forces of global-local relations. In Iwabuchi’s view, Japanese media companies have exported the Japanese experience of indigenized Western culture to Asia (20). In this way, people in Asia no longer consume “the West” but an indigenized or hybridized version of it (105).

Iwabuchi’s edited volume Feeling Asian Modernities (2004) provides the most sophisticated attempts currently available to theorize the content and flow of Japanese popular cultural. Contributor Lisak Yuk-ming Leung analyzes two popular Japanese dramas that debuted in Hong Kong in 1992 (Love Generation) and 1997 (Long Vacation). According to her, the Japanese ganbaru message (“to strive and to struggle hard”) has traveled across Asia through Japanese TV dramas that “embody Ganbaru messages in a new guise” (91). The ganbaru behavior is depicted by the dramas’ urban heroes, who “have been struggling in work and in relationships… encouraged by their counterparts to strive on” (92). The viewers of the dramas, for their part, have adopted the ganbaru message in varying intensities across age groups (100-102).

In the same volume, Yu-fen Ko argues that Japanese idol dramas play a role in Taiwan’s “latent ambivalence of ‘anxiety and desire’ for modernity” (108). In this context, Japanese dramas represent the “real life problems” that Taiwanese are facing (108). Lee Ming-tsung’s study, too, finds that “the cross-cultural practices of imagining in Taiwan and experiencing in Japan facilitate a transformation of cultural orientation to and self-identification with the dominant other, Japan” (130). In the same book, Siriyuvasak Ubonrat’s study of Bangkok and Dong-Hoo Lee’s study of South Korea provide similar results about the way Japanese popular culture products “project modernities.” These studies also suggest that the act of cultural consumption and the practice of Japanese culture lead to a strong identification with Japan and will eventually affect East Asia’s national or regional identity as a whole.

All of the studies mentioned above contain rich information and analysis related to the various practices of Japanese popular culture overseas. Their ultimate importance, I think, is in refuting Western globalization theorists’ notion of cultural homogenization. Globalization theorists have described a homogenizing world in which the evolution of business and cultural networks increasingly shape peoples’ economic destiny, identity, and culture (for example Druker 1993; Hannertz 1991; Huntington 1996; Kotckin 1992; Robertson 1991; Schiller 1976; Tomlinson 1991; and Wallerstein 1991). The overall picture is of supranational tribe-like cultural entities grouping to adjust to the new global order. The contribution of the specific ethnographic studies mentioned above to an effective rebuttal of that delusion lies in their rich accounts of cultural diversity and heterogeneous practices that remain resistent to the supposedly homogenizing forces of globalization.

The weakness of this literature, however, is its retention of a global-local paradigm. Most of these studies view the expansion of Japanese culture overseas as a part of a global process and overlook their own testimonies indicating that Japanese cultural commodities have a constricted circulation, a deeper acceptance, and a conspicuous impact within the cultural-geography of this region. To them, the global-local paradigm is employed as the only unit of analysis; the “local” is considered a receiver and indigenizer, while Japan is regarded as both indigenizer and mediator to the “global.” This tendency is a part of the wider phenomenon of engaging in contextual analysis and labeling the examined cultural practices as a part of a global process (see, for example, Craig and King 2002; and Hall 1995).

Interestingly, even those who do mention the conspicuous regional acceptance of Japanese culture in East Asia, do it matter-of-factly. Prominent studies describing “Japanization/Asianization” (Otake and Hosokawa 1998), “Pop Asianism” (Ching 1996), “Trans-Asian Cultural traffic” (Iwabuchi 2004), and “Pan East Asian popular Culture” (Chua 2003) tend to see these phenomena as tantamount to globalization in the East and Southeast Asian region. Because they do not think the “region” is a viable unit of analysis, the analysis suffers from the tendency to note the phenomenon only in passing. As a result, they fail to ask what kind of role intra-regional relations play in shaping the circulation and consumption of cultural products.

In this sense, Iwabuchi is correct in maintaining that Japan’s cultural influence has been conspicuous and immense in East and Southeast Asia. In contrast, many Japanese popular culture products, such as music, fashion accessories, and idol-culture, have rarely found receptive consumers outside the specific cultural geography of this region (Iwabuchi 2002: 47, 84). Perhaps this observation can lead us beyond the premises of globalization.

A Call for a Regional Paradigm

At this point, my argument is that we should try to construct a regional paradigm as a basis for analyzing transnational culture flows in East and Southeast Asia. In other words, we should see the “regional” not only as a process by which culture flows across national boundaries or as a manifestation of global-local relations, but as an analytical unit containing particular characteristics which differentiate it from the discourse of globalization.

An explicit harbinger is the fact that regions have become important in the world’s politics and economy, even in an era of globalization (Hettne et al. 1999; Mansfield and Milner 1999; Mittelman 1996). An indicator of this phenomenon is the progress achieved by the European Union, as well as other ongoing regional formation attempts in North America (NAFTA), South America (Mercosur), Africa (AU), Asia (ASEAN, EAEC), and Asia-Pacific (APEC).

In East and Southeast Asia, the economic achievements of the last three decades have increased the visibility of the region, whose formation has been generated by “market dynamism” and cross-border economic activities. This process continues despite an obvious lack of formal regional institutionalization and an emphasis on the informal, negotiated, and inclusive approach in regional policy, as some scholars have observed (Castells 2000; Frankel and Miles 1993; and Katzenstein 2002).

A few studies have accounted for the dynamism of the economy, suggesting that market-centered processes have been the main engines propelling East and Southeast Asian regionalization (Haggard 1997; Hatch and Yamamura 1996; Katzenstein and Shiraishi 1997; Petri 1993). A recent comprehensive study by the World Bank has underlined these findings, showing that since the mid-1980s intra-regional trade has grown at a rate roughly double that of world trade and higher than that of the intra-regional trade of NAFTA or the EU. According to the World Bank study, trade relations between most East and Southeast Asian countries have grown sharply in intensity, and the economic linkages and interdependence among the region’s economies have strengthened considerably (Ng and Yeats, 2003).

The rise of middle classes in metropolitan East and Southeast Asia is another indication. These middle classes are both the product and the stimulators of regionalization in East Asia and provide the model for others to follow. Approximately ten consecutive years of double-digit annual economic growth since the late 1980s have nurtured the emergence of East Asia’s middle classes. Observing their emergence, Shiraishi Takashi has argued that “they are the product of regional economic development which has taken place in waves under an American informal empire, over half a century, first in Japan, then in South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore, then in Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines and now in China” (2004: 33). (On East Asia’s middle classes, also see Chua 2000; Hattori et al. 2002; and Robson and Goodman 1996). 2 Their socio-economic power constantly generates demand for imported consumer goods and cultural products, invigorating the region’s consumerism and converging its markets.

In the field of culture as well, rapid developments have produced lasting changes. Examination of these changes may point the way to a regional paradigm that provides better tools for analyzing the manifestation, practice, and impact of popular culture in East and Southeast Asia. The main cultural features of East and Southeast Asia since the early 1990s are the overlapping confluences of American, Japanese, Chinese, and Korean cultures. Existing simultaneously and in varying intensities, they are continually shaping cultural scenes and lifestyles. People in East and Southeast Asia share a pool of popular culture products from which they may choose according to cultural preference, concurrently or supplementarily consuming American, Japanese, Chinese, Korean, and other cultural products. Millions of youth in Hong Kong, Seoul, Shanghai, and Jakarta covet the latest fashions from Tokyo, listen to the same genre of American pop music, watch Chinese dramas on television or DVD, read Japanese comic books, and go with friends to watch the latest Korean movie (Otmazgin 2005).

Cultural confluences in East and Southeast Asia, however, are selective—they mainly involve urban middle classes, not whole national populations .Cities are central to our understanding, as they are the junctions where cultural flows overlap with excessive consumerism. East Asia’s megacities (Bangkok, Hong Kong, Seoul, Shanghai, Singapore, Taipei, Tokyo, etc.) serve as matrices for cultural innovation, expansion, and mixing; they are where the construction of intra-regional and extra-regional consciousness culminates. In East and Southeast Asia, therefore, we should talk about a multi-layer interaction between metropolises, rather than between nation-states.

Moreover, regional collaborations between media companies and promoters are having a strong impact on the East and Southeast Asian cultural market. These players are essentially entrepreneurs in search of new business expansion opportunities, and they have been encouraged by the magnification of East and Southeast Asian media markets in the last two decades. Their activities consequently endorse the expansion of East and Southeast Asia’s culture markets, extend and strengthen regional cooperation and links, and provide substantial cultural content to the imagery of “Asia.”

Movies, Music, and Television

Pan-Asian movies are a conspicuous example. With their dovetailing of Asian and Western motifs, they have gained much popularity in East and Southeast Asia, and to a lesser degree in the American market as well. Movies like Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, Hero Jan Dara, 2046, Initial D, and Musa were produced and marketed transnationally. Some are ambitious co-productions involving staff members and actors from South Korea, China, Hong Kong, Japan, and Thailand. 3 Low production costs in places such as China, Thailand, and Malaysia provide the incentive to relocate production. The existence of potential consumers in the regional and global markets encourages marketing strategies that aim to include the widest range of audiences in East and Southeast Asia and beyond. The resulting imagery is affecting the way both regional and extra-regional audiences conceptualize “Asia.”

Regional collaborations are taking place in the field of music and television as well, testing the waters for the rise of an East and Southeast Asian popular culture and creating new cultural genres. More than the broadcast media industries, the primary tendency of music and television production in East and Southeast Asia is to develop regionally, rather than attempt to extend globally. Channel V is an important player. It is an Asian version of MTV that enjoys phenomenal popularity across East Asia. The channel continually introduces local and international pop and rock music to its wide cable television audiences. Channel V’s music programs often categorize the featured music as “Asian music,” which includes the pop music of artists and bands from different East Asian countries. Sony Music Entertainment is also working to create a pan-Asian music genre. In 2004 it produced a two-volume pop music collection featuring Japanese, Hong Kong, Taiwanese, and South Korean artists. The success of the album motivated the production of new volumes in 2005 that also included Thai music. 4

In the field of television, a few transnational alliances have been articulated; however, high production costs impede many transnational production attempts, leaving them in an embryonic stage. The importance of the few existing attempts lies in the overall entrepreneurial exploration and consequent transfer of cultural production know-how. In transnational television broadcasting, Star TV is Asia’s biggest entrepreneur in recent years, owning a wide variety of entertainment, news, and sports channels and creating a pool of consumers in 300 million homes ranging from China to India. Its strategy favors localizing content and broadcasting in Asian languages, especially Mandarin (Sinclair 1997).

Japanese music and television companies are also important players. A few have been gradually exploring markets in East Asia, spurred by both entrepreneurship and local demand. Pony Canyon and Avex Trax, for example, two of the big six Japanese music companies, have broadened and deepened their entry into East Asian media markets by moving from licensing agreements with local companies to opening their own branches. In the field of television, Amuse, Rojam, Fuji TV, and JET TV are notable. They engaged in various television broadcasts and productions in the 1990s, often based on Japanese formats, establishing ties with local companies and media organizations. These Japanese companies have not only marketed Japanese music and television programs, but have been seen as examples and models by local cultural industries in East Asia.

These are only a few of the developments in the regional cultural scene of East and Southeast Asia in the last few decades. They have created a new reality in which a wide domain of East and Southeast Asian urban middle classes share a variety of cultural products and opportunities. Although they are embedded in different spatial locations with different incomes, a comparable level of lifestyle consumption is available to most, if not all. Today’s Chinese, Malaysian, and Indonesian urban middle classes can aspire to the same cultural access and preferences as their counterparts in Seoul, Singapore, and Bangkok.

In sum, markets and communities in East and Southeast Asia are converging as a result of economic, social, and cultural forces. Throughout the cities of this region, especially, markets for popular culture and mechanisms for cooperation are being constructed, processes that lay a solid discursive and conceptual space for analyzing the dynamic of regional cultural confluence. The examination of popular culture flows in this light is both more detailed and more accurate than the discourse (and rhetoric) of global-local relations, with its implicit or explicit emphasis on homogenization. A regional paradigm which takes account of local and regional particularities might be more useful in understanding cultural flows in this region.

Nissim Kadosh Otmazgin

Ph.D candidate, Kyoto University

Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia. Issue 8-9 (March 2007). Culture and Literature

References

Alison, Anne. 2000. “Can Popular Culture Go Global?: How Japanese ‘Scouts’ and ‘Rangers’ Fare in the US.” In A Century of Popular Culture in Japan, ed. Douglas Slaymaker. U.S.A.: Edwin Mellen Press.

Castells, Manuel. 2000. End of Millennium. Oxford: Blackwell.

Ching, Leo. 1996. “Imagining in the Empires of the Sun: Japanese Mass Culture in Asia.” In Contemporary Japan and Popular Culture, ed. John W. Treat. Great Britain: Curzon.

Craig, Timothy J., and Richard King, eds. 2002. Global Goes Local: Popular Culture in Asia. Canada: UBC Press.

Craig, Timothy J., ed. 2000. Japan Pop! Inside the World of Japanese Popular Culture. U.S.A: M.E. Sharpe.

Chua, Beng-Huat. 2003. “The Making of East Asian Popular Culture.” Paper presented in the Carolina Asia Center, University of North Carolina.

Chua, Beng-Huat. 2000. “Consuming Asians: Ideas and Issues.” In Consumption in Asia: Lifestyles and Identities, ed. Beng-Haut Chua. London: Routledge.

Drucker, Peter. 1993. Post Capitalist Society. New York: Harper Business.

Frankel, Jeffrey A., and Miles Kahler. 1993. “Introduction.” In Regionalism and Rivalry: Japan and the United States in Pacific Asia, ed. Jeffrey A. Frankel and Miles Kahler. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Haggard, Stephan. 1997. “Regionalism in Asia and the Americas.” In The Political Economy of Regionalism, ed. Edward D. Mansfield and Helen V. Milner. New York: Columbia University Press.

Hall, Stuart. 1995. “New Cultures for Old.” In A Place in the World? Places Cultures, and Globalization, ed. D. Massey and P. Jess. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hannertz, Ulf. 1991. “Scenarios for Peripheral Cultures.” In Cultural Globalization and World Systems, ed. A. King. London: Macmillan.

Hatch, Walter, and Kozo Yamamura. 1996. Asia in Japan’s Embrace: Building a Regional Production Alliance. Hong Kong: Cambridge University Press.

Hattori, Tamio, Funatsu Tsuruyo and Torii Takashi, eds. 2002. Ajia Chukanso no Seisei to Tokushitsu [The Emergence and Features of the Asian Middle Classes]. Tokyo: Ajia Keizai Kenkyusho.

Hettne, Björn, Inotai András, and Shukle Osvaldo. 1999. Globalization and the New Regionalization. U.K.: Macmillan Press.

Honda, Shiro. 1994. “East Asian’s Middle Class Turns into Today’s Japan.” Japan Echo 21, 4.

Huntington, Samuel P. 1996. The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Igarashi, Akio.1997. “From Americanization to ‘Japanization’ in East Asia!?.” The Journal of Pacific Asia 4: 3-20.

Ishii, Kenichi. 2001. Higashi Ajia no Nihon Taishou Bunka [Japanese Mass Culture in East Asia]. Tokyo: Sososha.

Iwabuchi, Koichi. 2002. Recentering Globalization: Popular Culture and Japanese Transnationalism. United States: Duke University Press.

Iwabuchi, Koichi, ed. 2004. Feeling Asian Modernities: Transnational Consumption of Japanese TV Dramas. Hong Kong: University of Hong Kong Press.

Iwao, Sumiko. 1994. “Popular Culture Goes Regional.” Japan Echo 21, 4 .

Katzenstein, Peter J. 2002. “Variations of Asian Regionalism.” In Asian Regionalism, by Peter J. Katzenstein, Natasha Hamilton-Hart, Kozo Kato, and Ming Yue. Ithaca: Cornell University East Asia Program.

Katzenstein, Peter J., and Takashi Shiraishi, eds. 1997. Network Power: Japan and Asia. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press.

Kotckin, Joel. 1992. Tribes: How Race, Religion and Identity Determine Success in the New Global Economy. New York: Random House.

Mansfield, Edward D., and Milner V. Helen. 1999. “The New Wave of Regionalism.” International Organization 53, no. 3: 589-627.

Martinez, D. P., ed. 1998. The Worlds of Japanese Popular Culture: Gender, Shifting Boundaries and Global Cultures. China: Cambridge University Press.

Mittelman, J. 1996. “Rethinking the ‘New Regionalization’ in the Context of Globalization.” Global Governance 2: 189-213.

Mori, Yoshitaka, ed. 2004. NishikiKanryu: “Fuyu no Sonata” to Nikantaishoubunka no Genzai [Japanese Style, Korean Boom: ‘Winter Sonata’ and Current Japanese-Korean Mass Cultural Relations]. Japan: Serika Shobo.

Ng, Francis, and Yeats, Alexander. 2003. “Major Trade Trends in East Asia: What are Their Implications for Regional Cooperation and Growth?” The World Bank Development Research Group, Policy Research Working Paper No. 3084 (June).

Otake, Akiko, and Shuhei Hosokawa. 1998. “Karaoke in East Asia: Modernization, Japanization, or Asianization.” In Karaoke around the World: Global Technology, Local Singing, ed. Toru Mitsui and Shuhei Hosokawa. London: Routledge.

Otmazgin, Kadosh Nissim. 2005. “Cultural Commodities and Regionalization in East Asia.” Contemporary Southeast Asia, 27 (3): 499-523.

Petri, Peter A. 1993. “The East Asian Trading Bloc: An Analytical History.” In Regionalism and Rivalry: Japan and the United States in Pacific Asia, ed. Jeffrey A. Frankel and Miles Kahler. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Robertson, Ronald. 1991. “Social Theory, Cultural Relativity and the Problem of Globality.” In Cultural Globalization and World Systems, ed. A. King. London: Macmillan.

Robison, Richard and Goodman S.G. David. 1996. “The New Rich in Asia: Economic Development, Social Status and Political Consciousness.” In The New Rich in Asia: Mobile Phones, McDonalds and Middle-Class Revolution, ed. Richard Robison and David S.G. Goodman. London: Routledge.

Schiller, H. 1976. Communication and Cultural Domination. New York: M.E. Sharpe.

Schodt, Frederik. 1996. Dreamland Japan: Writing on Modern Manga. Berkeley: Stonebridge Press.

Shiraishi, Saya. 2000. “Doraemon Goes Abroad.” In Japan Pop! Inside the World of Japanese Popular Culture, ed. Timothy J. Craig. USA: M.E Sharp.

Shiraishi, Takashi. 2004. “The Rise of New Urban Middle Classes in Southeast Asia: What is its National and Regional Significance?.” Paper presented in the Core University Program Workeshop, Kyoto University, October.

Sinclair, J. 1997. “The Business of International Broadcasting: Cultural Bridges and Barriers.” Asian Journal of Communication 7, no. 1: 137-155.

Tomlinson, John. 1991. Cultural Imperialism. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Treat, W. John, ed. 1996. Contemporary Japan and Popular Culture. Great Britain: Curzon.

Wallerstein, Immanuel. 1991. Geopolitics and Geoculture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Notes:

- Questionnaire surveys and interviews were conducted by the author among 239 university students in Hong Kong (June 2004), Bangkok (February 2005), and Seoul (April 2005). The questionnaires included 19 open-ended questions and 2 multiple-choice questions. I asked about the students’ cultural consumption patterns in general and their consumption of Japanese popular culture in particular, and about their attitude and opinions regarding various aspects of Japan’s society and state. I am grateful to Dr. Ubonrat Siriyuvasak (Chulalongkorn University) and Dr. Shin Hyun Joon(Sungkonghoe University) for their enormous help in conducting the questionnaires. ↩

- In these works, East Asian middle classes are generally classified as educated and working as professionals, technicians, clerks, managers, business executives, engineers, and accountants, for example. ↩

- See coverage of these movies in Newsweek, 21 May 2001, 15 December 2004, and Special Edition, July- September 2001; and Time, 21 January 2002. ↩

- The Sony Music Entertainment regional office in Hong Kong has been strategically encouraging its branches in East Asia to produce constellation albums that include transnational collaboration of music artists. Interviews in Bangkok and Seoul, February and April 2005. ↩