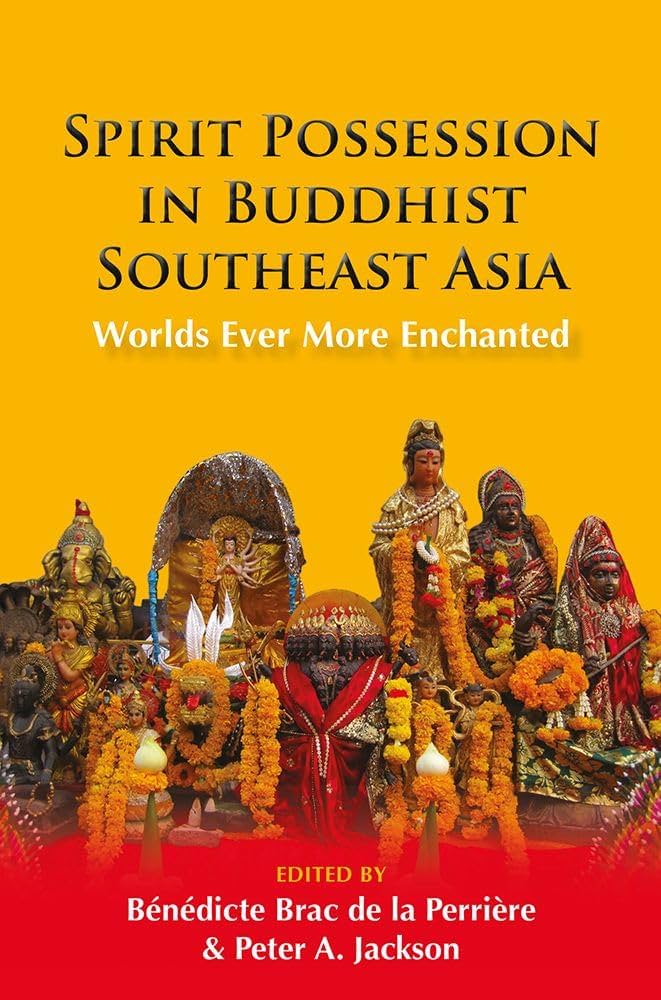

Title: Spirit Possession in Buddhist Southeast Asia: Worlds Ever More Enchanted

Eds. Bénédicte Brac de la Perrière and Peter A. Jackson

(Nias-nordic Institute of Asian Studies, 74). Copenhagen: NIAS Press, 2022

While the study of spirit possession, whether demonic, prophetic and oracular, or a vehicle for contacting deceased loved ones has generally been the purview of Afro-Caribbean, Afro-Brazilian, and Catholic Studies on the one hand or the sociological study of mediumship and Spiritualism in 19th century America and Europe on the other, there has been a rise in the study of it in Buddhist Studies. Previous studies have looked at “state” oracles in Tibet or talking corpses in India, Brac de la Perrière and Jackson’s new edited volume turns the focus to Southeast Asia, traditionally seen in Western scholarship as the most traditional (a word whose suspect use have not been adequately interrogated) branch of Buddhism. Their welcome volume combined with books over the past decade by Patton, Kitiarsa, Rozenberg, Taylor, Dror, Jackson and Brac de la Perrière themselves, and several others are revealing what Terwiel, Spiro, and Tambiah attempted in the 1970s, to disassociate Theravada from any notion of orthodoxy or conservative forms of Buddhism (as if there are any). While there are some of the usual concerns with cohesiveness and focus that come with boundary-pushing edited volumes with contributors from diverse scholarly backgrounds, this volume should be standard reading for all students in modern and contemporary Buddhist Studies. We will briefly describe the chapters and then suggest some possible places this volumes leads and some missed opportunities.

The introduction is variegated and expansive. It is strongest when discussing the relaxing of government regulation and the rise of capitalism and post-cold-war economic as they allowed for the efflorescence of spirit cults and practices. This is where Peter Jackson’s expertise really shines as he is largely the founder of the field of Capitalism and religion in Thailand. However, Brac de la Perrière’s focus on ritual and Burmese Studies provides a nice balance and this book, while certainly geared more to the social scientist/theorist in the fields of Anthropology, Politics, Economics, and Sociology is accessible to experts in literature, music, art history, and the more humanistic approaches in the study of religion. The introduction almost tries to do too much though. In trying to prepare the reader for the eclectic and fascinating chapters, it doesn’t present a coherent argument. However, honestly, I don’t think we, the reviewers, could do any better. The introduction is honest in its inability to capture these various studies under one thesis. The introduction, because of the diverse content, could only do so much. Still, some other more chapter-specific sub-sections in the introduction (such on oneiric space, or pantheons) were hard to follow without having read the book, and unfortunately gave the introduction a sense of being adrift. They did lead to a suggestion we have below though.

Chapter one by Paul Sorrentino considers how the Vietnamese pantheon (rarely are studies of Vietnamese Buddhism included in more general books on mainland Southeast Asian Buddhism, which are almost always universally Theravada focused and so this inclusion was refreshing), despite it’s apparent ‘Chinese character’, actually supports Vietnamese local sovereignty and territory. This chapter explains the dual impetus for the pantheon to be both specific/consisting of discrete identities and stories and generalized/classified. This model could be useful when looking at lists of past Buddhas, particularly in the ways this ideology meets with art and artistic methods like printing and copying. Sorrentino begins to discuss how the tensions between these two directions might reflect ideas about managing the state as well. He also gestures towards a gendered dynamic within the pantheon as well, with women and the land connected, and men and bureaucracy being connected. However, this brings up several unanswered questions: 1) since bureaucracy also seems more connected to Chinese influence, does that mean women might be considered more local than men/more pure from outside influence?; 2) why does the pantheon manifest ‘sovereignty’ or masculinity as bureaucratic rather than in violence or physical strength? Is this a Chinese influence or a modernizing one?; 3) can we see bureaucracy as magic? Note: on page 52 jewelry is spelled “jewelry.”

Bénédict Brac de la Perrirèr’s chapter discusses the worship of Mya Nan Nwe, a naga at Botataung who was moved outside the pagoda and temple compound when her popularity became uncomfortable to the abbot of the temple. Like with the more general political religious freedom giving rise to new practices, so too did being brought outside the temple unbind the naga from temple propriety, allowing her devotees freedom of practice in other ways. In Thai there is the idea of riap roi— not just appropriate, but appropriate for the specific context, time, and place, which might be relevant here for conceptualizing the boundaries between practices while not condemning one or the other inherently. Perrirèr also discusses how the worship and festival surrounding Mya Nan Nwe grew, demonstrating that ritual spaces don’t just accumulate material objects, they also accumulate ritual forms, becoming more elaborated as time and devotion continue.

In chapter 3, Visisya Pinthongvijayakul discusses monastic mediums in Thailand. This chapter, like a few others in this book, doesn’t adequately theorize the parts of practice being discussed, or the ways they relate to each other. Despite discussing monastic mediums, uses the term “Buddhism” in contrast to spirit mediumship and sing saksit. While not necessarily advocating for a total return to Sprio’s “dharmic Buddhism” and “kharmic Buddhism,” when discussing monastic and non-monastic practices, we should be careful about calling the non-monastic — “not Buddhism” – especially considering that there are actual monks performing these apparently “not Buddhist” rituals. Later in the chapter, Pinthongvijayakul discusses the way the two traditions interpenetrate, are reciprocal and co-dependent, and comprise each other, but that conclusion is not reflected in his language in the chapter overall. Also, like many other authors in this book, Pinthongvijayakul reflects on Weber’s incorrect prediction about a disenchanted future. However, we wonder if that is actually a more interesting question that perhaps asking why we see a current efflorescence of enchantment or if it ever actually disappeared. Still, this chapter presents a very interesting case study and brings up several issues discussed in other chapters. Note: on page 115, there is another minor editing error – “khathaa11” without a space between the word and number.

Kazuo Fukuura’s chapter connects well to the previous chapter because it mentions Weber’s disproven hypothesis of disenchantment, which is unfortunate, but this chapter does a nice job in discussing the micropolitics of mediumship, and their concern for financial security and the need for funeral fees, as reflected in Assembly of Lan Na (Northern Thai) spirit mediums. This chapter has a lot of interesting local information about Lan Na Buddhism for the non-expert, but is theoretically less robust than others. The sections on the rituals of the three kings and the Kuang Sing ritual were particularly interesting. Most importantly the author stresses the innovations of the mediums when writing: “they are something new that has emerged out of a creative inheritance, maintenance, and development of religious traditions, and they demonstrate the creativity of mediumship and its ritual practices to adapt to, negotiate with, and influence the social environment.”(142)

Continuing with this focus on negotiation and creative adaptation, Paul Christensen’s chapter focuses on Cambodia. He stresses that Brahmanism has thrived in modern Cambodia because “Brahmanism is, even more than Buddhism, a category of negotiation and context.”(151) Generally, Christensen’s work is useful in the ways it tries to define terms more than other chapters. It is very deliberate in its use of “Brahmanist” vs. “Buddhist” language, as Christensen describes why he doesn’t use the official definition of ‘Cambodian Buddhism’ to better illustrate the explicit rejection of Buddhism by some ‘Brahmanist’ actors, as well as the simultaneous ‘Buddhaization’ and ‘Brahmanization’ of practices. This chapter raised questions about the value of money versus the value of merit, as well as the general morality of money, and the changing importance of morality/virtue.

In chapter six, Niklas Foxeus considers moral action within prosperity Buddhism. Indeed, his chapter is where we get a more fleshed-out idea of what a prosperity cult is in Buddhism (although a broader comparison with prosperity cults in Islam and Christianity might have helped to distinguish what differences we can learn from studying Buddhist examples). Foxeus thoroughly explains how prosperity cults reflect a localized modernity, inflected by Burmese desires and cultural technologies. This chapter also considers economic changes of caused by modern contexts, that, as argued by White elsewhere, financial uncertainty produces other formsof/desires for control. In other words, the elements of chance and randomness (in the lottery for example), as well as the fantasy of wealth if won, are thus particularly well suited to prosperity cults.

In Poonnatree Jiaviriyaboonya’s contribution there is a consideration of “discourses of modernity.” It offers a case study of a Cambodian student, Sovanna, stuck between going abroad to study and possibly being away from her family if something bad happens, and regretting never studying for the rest of her life. She meets with a fortune teller named Grū Bun, who uses an accumulated number of sources in his work, and approaches the future flexibly, and in dialogue with his clients. There were two directions this article could have gone further: the first in considering the psychological or comforting service Grū Bun offers, and the second in considering the fetish object— study abroad— and the quasi mystical/fantastical effect that Sovanna believed studying abroad would have on the rest of her life. However, more than other chapters it allows readers to better respect the emotional lives of practitioners and seekers.

Next, Megan Sinnott presents a very interesting chapter on how child spirits/luk krok/kuman thorng have become more sentimental—adopted and cared for— and less material or separated from literal bodies, rather than transactional and embodied. This reflects an overall separation of these children from their more ambivalent qualities, like death and danger. The disembodied children are by contrast, alive (if immaterial) and supportive members of the family. In addition to theorizing the sterilization and new timelessness of the child spirits, this chapter also considers the way capitalism and the market permits this kind of variety, responding to desires without reference to the fact that the desires of some may offend the sensibilities of others. This specific analysis of the market pairs nicely with other more general arguments related to capitalism found in this book. This chapter also highlights the uniqueness of the child spirits.

In chapter nine, Irene Stengs uses her vast experience in studying political and royal cults to discusses visions and dreams, and conceptualizes encounters with historic characters as dimensions of the present rather than as realizations of the past. This chapter discusses historic central Thai figures, leading the reader to understand this particular manifestation of regional pride as a valence of national pride (in contrast to other situations, where regional pride is exceptionalist and raises the local above the nation, rather than with it). This argument was very important and I hope the reader does not lose sight of its importance so deep into this long and detailed rich volume.

Finally, Benjamin Baumann offers perhaps the most theoretical chapter. Although it was very dense, particularly at the beginning, the less theoretically curious should not abandon this piece. Despite the long theoretical framing, in which Baumann introduces many key concepts (although, it would have helped if he defined “language games,” a phrase used throughout) he asserts a very important argument – that we consider animism as a relational ontology, which places it along a different axis than “Buddhism” so that the two terms overlap but do not need to influence each other (perhaps like orthodoxy and orthopraxy). Baumann also argues in favor of the Southeast Asian person as a dividual, (rather than individual), as local concepts of personhood are composite. This dividuality allows for many ritual activities and beliefs within the Thai possession complex.

The editors further helped the readers by including a conclusion by probably the most experienced expert in spirit mediumship in Southeast Asia – Erick White. His work helps draw together directions for future research. However, his conclusion couldn’t complete the herculean task of bringing these diverse scholars and studies under a unified and cohesive argument. Indeed, he highlights this issue as well, writing that the plurality of practice does not allow for easy comparison. However, despite the difference in objects, these chapters could have felt more cohesive if they had been considering a similar handful of questions. For instance, the chapters feel most congruent where they consider morality and prosperity. But as they stand, the reviewers’ understanding of each chapter was not changed as we read the next. So, while this book might not end up being more than the sum of its parts, the parts are fascinating, original, well-researched, clearly written, and useful.

One direction for future research lacking in this book is a study of malevolent forces. Several chapters consider moralizing previously ambiguous spirits, but none fully address exorcisms, sicknesses, and the dangers associated with malevolent spirits. Are there simply fewer and fewer of these dangerous spirits or experiences as spirit cults get sterilized and ‘Buddha-ized’ or are they still important features of Southeast Asian spirit possession, though not mentioned in this book? A study of the nefarious, the dangerous, and the out-of-control would pair nicely with this book.

A second missed opportunity is briefly mentioned in the introduction — oneiric space. One of the least studied aspects of religion in Southeast Asia, despite its prevalence in historical chronicles, popular culture (themes of many films and scenes of popular television programs) and a common source for the prognostications offered by soothsayers and fortune tellers are dreamscapes, dream interpretation, and dream symbolism. This body of knowledge circulates in different forms in the region and royals and commoners, monastics and laity alike draw from it, interpret it, and reimagine the significance of it in different ways. However, despite books available in Southeast Asian languages on dream meanings, harbingers, and narratives, as well as being sources of art, music, and literature, this was a subject not included in any serious or sustained way by the authors. This is not a criticism, because it is unfair to criticize was is not contained in this volume, when there is so much significant historical and anthropological content offered, but a suggestion for future research that the editors and authors inspired.

Reviewed by Claire Elliot* and Justin Thomas McDaniel**

*Claire Elliot is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Religious Studies at the University of Pennsylvania.

**Justin Thomas McDaniel is the Kahn Endowed Chair of the Humanities at the University of Pennsylvania