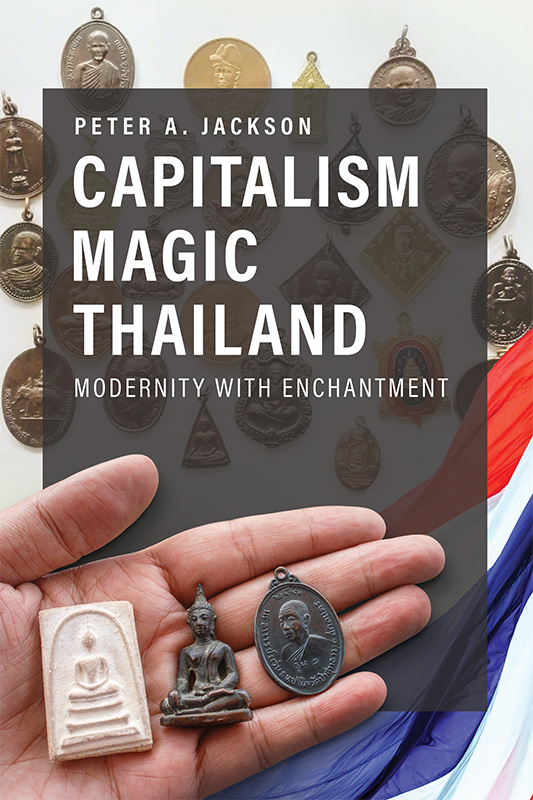

Title: Capitalism, Magic, Thailand: Modernity with Enchantment

Author: Peter A. Jackson

Publisher: ISEAS Publishing, 2022

More than three decades ago, Stanley Tambiah (1990, p. 83) contended that the disconcerting character of ritual for moderns “will only disappear when we succeed in embedding magic in a more ample theory of human life in which the path of ritual action is seen as an indispensable mode for men […] of relating to and participating in the life of the world”.

It is no coincidence that the last chapter of Peter A. Jackson’s enthralling venture into the enchanted world of post-Cold War Thailand closes with this auspicious quote (p. 313). In fact, Capitalism, Magic, Thailand (2022, ISEAS) turns Tambiah’s hope into an unprecedented achievement.

Overcoming dominant epistemological and disciplinary divides in social sciences scholarship, this meticulously documented and theoretically sophisticated study of the Thai cults of wealth provides the most comprehensive and up-to-date analysis of the multiple ways in which (Buddhist, Brahmanical, Chinese, royal and animist) ritual, neoliberal capitalism, visual technologies, and digital media actualise intersecting processes of (non-rationalised) enchantment in Thailand and across the globe – a powerful, perhaps definitive confutation of Enlightenment theories of modernity, including Max Weber’s fallacious prediction of rationalisation, secularisation, and disenchantment as unavoidable conditions of the modern world.

Research and scholarship, Jackson warns, need to go “where the river of Thai religion now flows” (p. 15), beyond temples and monasteries: in marketplaces, online stores, and shopping m alls. Cruising down the river of Thailand’s spiritualised capitalism, following its thousand streams and rivulets of interpenetrating, contextually distinct cultic forms, Jackson presents his readers with charismatic images of prestige (barami) through which various deities are made accessible and marketable as objects of ritual consumption: a major gas producer’s advertisement material includes the pictures of six magic monks (kejy ajan); an inflight magazine details how material wealth was brought to Bangkok’s upmarket shopping district by Hindu deities; a fortune teller in Northeast Thailand uses Facebook to provide his (Chinese, Singaporean, Taiwanese, and Malaysian) customers with divinatory business advise – Thailand has never been more enchanted. As the author stresses, this ritual-centred amalgam of ontologically-distinct cults is not an awkward survival from a supposedly superstitious, pre-Buddhist past. On the contrary, the prosperity movements at the core of Jackson’s book constitute a novel, exquisitely modern religious phenomenon, a post-rational response to the unpredictability of Thailand’s “casino capitalism” (Klima, 2006), and a set of pragmatic and highly plastic cultural forms “in a society that has located the […] theoretically recalcitrant globalised market at its heart” (p. 296). The de-centralised, de-territorialised, and capillary structure of both the market and the internet have indeed delocalised magical phenomena and made local spirits available to national audiences, while print and visual media are operating as “technologies of enchantment”, creating a media-induced aura around a number of increasingly popular cultic figures. As a result, “movements that began as expressions of popular devotion outside of official Buddhism have moved from the sociological margins to the mainstream of Thai religious life” (p. 2). At the same time, the kala–thesa (time and space) contextualised separation of private (animist) and public (Buddhist) ritual domains – emerged as a political strategy of cultural mediation during Thailand’s semi-colonial period – is now more flexible, as “elite participation in supernatural ritual has become an increasingly visible and politically significant dimension of the symbolic exercise of power” (p. 122-3). Paradigmatic, in this respect, is the case of General Prayuth Chan-o-cha showing off his collection of amulets at a conference press in 2016 (ibid.).

alls. Cruising down the river of Thailand’s spiritualised capitalism, following its thousand streams and rivulets of interpenetrating, contextually distinct cultic forms, Jackson presents his readers with charismatic images of prestige (barami) through which various deities are made accessible and marketable as objects of ritual consumption: a major gas producer’s advertisement material includes the pictures of six magic monks (kejy ajan); an inflight magazine details how material wealth was brought to Bangkok’s upmarket shopping district by Hindu deities; a fortune teller in Northeast Thailand uses Facebook to provide his (Chinese, Singaporean, Taiwanese, and Malaysian) customers with divinatory business advise – Thailand has never been more enchanted. As the author stresses, this ritual-centred amalgam of ontologically-distinct cults is not an awkward survival from a supposedly superstitious, pre-Buddhist past. On the contrary, the prosperity movements at the core of Jackson’s book constitute a novel, exquisitely modern religious phenomenon, a post-rational response to the unpredictability of Thailand’s “casino capitalism” (Klima, 2006), and a set of pragmatic and highly plastic cultural forms “in a society that has located the […] theoretically recalcitrant globalised market at its heart” (p. 296). The de-centralised, de-territorialised, and capillary structure of both the market and the internet have indeed delocalised magical phenomena and made local spirits available to national audiences, while print and visual media are operating as “technologies of enchantment”, creating a media-induced aura around a number of increasingly popular cultic figures. As a result, “movements that began as expressions of popular devotion outside of official Buddhism have moved from the sociological margins to the mainstream of Thai religious life” (p. 2). At the same time, the kala–thesa (time and space) contextualised separation of private (animist) and public (Buddhist) ritual domains – emerged as a political strategy of cultural mediation during Thailand’s semi-colonial period – is now more flexible, as “elite participation in supernatural ritual has become an increasingly visible and politically significant dimension of the symbolic exercise of power” (p. 122-3). Paradigmatic, in this respect, is the case of General Prayuth Chan-o-cha showing off his collection of amulets at a conference press in 2016 (ibid.).

While this ground-breaking re-reading of Thai modern history reduces significantly the prominence of (doctrinal) Theravada Buddhism in the interpretation of the country’s societal transformations, Jackson nonetheless recognises that “in the Thai religious amalgam, the […] magical power of Brahmanical and other forms of ritual is enabled by the authorizing barami […] of Buddhist rituals” (p. 163). This means that the new prosperity cults at the centre of his analysis are incorporated into an overarching Buddhist order of meritorious hierarchy, which locates new (non-Buddhist) deities and rituals in established stratified relations of superiority and inferiority. The political implications of this are yet to be fully explored.

Capitalism, Magic, Thailand consists of seven chapters divided into three substantive parts. Part One (Why Religious Modernity Trends in Two Opposing Directions) discusses critically Weber’s sociology of religion in light of Bruno Latour’s analysis of modernity as an intrinsically contradictory, bifurcated condition that produces both rationalising purification and hybridising practice. In the latter’s religious fields, ritual, body and performance – as opposed to doctrine, mind, and truth – are the key means through which the enchanting effects of Thailand’s capitalistic modernity are recursively enacted. Part Two (Thailand’s Cults of Wealth) examines an expanding variety of ritual forms (prosperity cults of royal figures, of Chinese and Hindu deities, of magic monks, of empowered amulets, and of spirit possession) that have been flourishing across the country since the last decade of the twentieth century. This section forms the empirical core of the book, but it also sets out a nuanced conceptual framework to understand how these discreet cultic forms are amalgamated into an overarching, doctrinally inconsistent symbolic complex that involves multiple ritual specialists engaging in symbolic exchange with religious, mediatised and commercial spaces. Part Three (How Modernity Makes Magic) expands the study’s comparative scope beyond Thailand, offering startling new insights on the entanglements between modernity and magical enchantment at the global level.

In the book conclusion, the author announces the forthcoming publication of an associated and complementary study, which will dig into the role of politics in the efflorescence of the Thai cults of wealth (p. 326). This new exciting project will further deconstruct modern analytical dichotomies (e.g. the religious-secular distinction) in Thailand, establishing new, fertile lines of comparative research on the “political-theological nexus” in Asia (Bolotta, Fountain and Feener, 2020). While waiting impatiently for this new volume, Capitalism, Magic, Thailand’s readers will no doubt fully enjoy Jackson’s masterly work as a major milestone in Thai studies literature, which will have a lasting impact on scholarship well beyond area studies, promoting radical epistemic shifts in the interdisciplinary investigation of global modernity.

Reviewed by Giuseppe Bolotta

Giuseppe Bolotta is Assistant Professor of Southeast Asian Studies in the Department of Asian and North African Studies, Ca’ Foscari University of Venice.

References

Bolotta, G., Fountain, P. and Feener R.M. (eds.) (2020), Political Theologies and Development in Asia: Transcendence, Sacrifice, and Aspiration. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Klima, A. (2006), “Sprits of ‘Dark Finance’ in Thailand: A Local Hazard for the International Moral Fund”. Cultural Dynamics, 18(1): 33–60.

Tambiah, S.J. (1990), Magic, Science, Religion and the Scope of Rationality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.