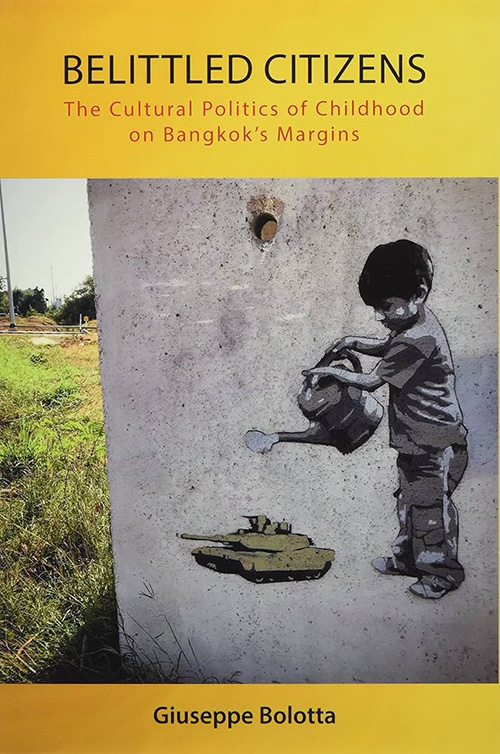

Title: Belittled Citizens: The Cultural Politics of Childhood on Bangkok’s Margins

Author: Bolotta, Giuseppe

Copenhagen: NIAS Press, 2021

Accessible, engaging and original, Giuseppe Bolotta’s book Belittled Citizens: The Cultural Politics of Childhood on Bangkok’s Margins is an excellent investigation into the fascinating social worlds and agency of dek salam (slum children) in Bangkok, which in turn reveals endemic social inequalities and the broader socio-political, religious and economic transformations in Thai society in recent years. Bolotta’s monograph disrupts both the fixed image of dek salam by the Thai state as ‘bad children of Bangkok’, and the portrayal of them as ‘innocent victims’ by humanitarian organisations. Instead, he illustrates the ‘kaleidoscopic nature of the identities projected by these children’ (p. 3). Their complex and dynamic subject positions, adaptability and agility result in dek salam taking on various roles in different social contexts—they are simultaneously the victim, phu noi (small people), social deviants, sacred, spiritually immature, God’s beloved children. Positioning ‘childhood’ as a political category, Bolotta provides a layered and careful analysis not only of how the ‘marginal childhood’ of the urban poor is a site of contention among various institutions (the Thai militarised state, engaged Buddhism, Catholic missionaries, Western NGOs), but also of the children’s constrained agency, resourcefulness, and complex construction of their selves and their worlds.

Bolotta’s first encounter with dek salam was in 2008 when he did a short stint as a volunteer at Saint Jacob’s Centre (pseudonym)—a Catholic NGO operating in one of Bangkok’s numerous slums to provide residential care to underprivileged children and young people aged 5 to 18. He then returned in 2010 for his PhD fieldwork and, over the course of six years (2010-2016), immersed himself in myriad social contexts where dek salam spend their lives and where their marginal childhood is being contested and negotiated—ranging from slums, schools, Buddhist temples, Catholic NGOs to state and international aid organisation as well as on social media. The backdrop to the fieldwork was the major political turmoil that deeply divided the country and resulted in the resurgent of authoritarianism. While youth and children have taken centre stage and emerged as political actors in recent years to challenge the militarised state’s prescribed notion of childhood, the voices of marginalised children such as dek salam rarely feature. Regarded by the state and general public as ‘not-Thai-enough’ or ‘social deviants,’ dek salam are deemed ‘belittled citizens of loose morals’ (p.18), subjects of disciplining rather than agents of knowledge. By focusing on ‘politically unnoticed’ and ‘ontologically uncommon’ subjects, Bolotta’s work is a welcome contribution to emerging literature in anti-normative categories of childhood—an area of work that is much needed in the context of Thailand.

The book is organised into two parts, which work well to form a juxtaposition between the structure and agency. Part One examines the various ways in which childhood—and specifically that of the urban poor—is interpreted, constructed and addressed by both religious and secular actors at multiple levels—local, national, supranational. From the Thai state’s model of ‘a good Thai child’ to Buddhist karmic lens of (poor) children as spiritually incomplete and the Catholic declaration of (poor) children as God’s beloved, the chapters in Part One expose how these competing and drastically different interpretations of childhood result in a complex constellation of social worlds which the children inhabit. In addition to thorough analysis of the Thai educational system and its role in subject formation, Part One also contains rich historical information and critical discussion of both the engaged Buddhism movement and Catholic missionaries and their significant roles in (re)framing public notions of childhood. Bolotta also examines how aid agencies (secular and religious) have ‘transformed the landscape of urban poverty in Bangkok into a cosmopolitan, child-centred field of power’ (p. 4).

Part Two examines the children’s own voices, embodied experiences and cultural practices within these complex structures. Bolotta observes that children’s circulation through these ideologically diverse institutions provides them with rich opportunities for socialisation and diverse cultural reference points to draw on as they construct their identities. The chapters in Part Two thus immerse readers in their rich social worlds. The trust between Bolotta and the children is evident in their interactions and encounters, resulting in rich ethnographic vignettes and intimate observations. In Chapter 6 Beyond the ‘Thai Self’, the contribution of Bolotta’s longitudinal ethnographic research especially shines, as he traces fascinating life trajectories and self-transformations of many of dek salam over a decade. Bolotta convincingly reveals the fluid and ever-changing subjectivities of these youth, which over the years have resulted in complex, multiple and often, contradictory, sense of selves. The self-polysemy can, at times, appear rather disconcerting such as in the lifestory of Naen—a Catholic teacher who is also a prostitute—or that of Two—a Karen man adopted by an elite Thai woman as a part of her civilising mission project, who carries a heavy weight of secrecy of his origin. The accounts in Part Two highlight state violence against Dek salam, examining how the ethno-nationalist norm of the ‘good Thai child’ denigrates these children and their familial and cultural roots, creating shame and potentially generating severe self-bifurcations. At the same time, Bolotta argues this self-polysemy can also be a form of agency and subversion, as in the case of Am’s political activism. Bolotta observes how, compared with their Bangkok upper-middle class counterparts, dek salam are less embedded in Thailand and instead display what Appadurai calls ‘bottom-up cosmopolitanism,’ allowing them to be ‘ideal mediators of cultural languages and generational brokers of national and post-national (local and global) imaginaries’ (p. 183) with the capacity to challenge the militarised ‘Thainess’ and widen future possibilities of being ‘Thai’.

Bolotta’s thorough analysis of the Thai and careful observations of slum children’s everyday lives in Bangkok make rich contributions to the fields of childhood studies and Thai studies alike. The commitment to follow the same group of children in itself provides an important contribution to understanding how various life stages affects identity formations. Scholars of childhood studies, Thai studies, as well as those interested in education, the state and non-profit studies, are sure to benefit from this meticulous and provoking book.

Janepicha Cheva-Isarakul

Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand