When the internet became available to the world a few decades ago, people were enthusiastic about it being a conduit to positive social changes. That expectation grew when social media platforms emerged in the early 2000s as they expected social media to facilitate social movement, making it easier for people to overcome collective action problems; creating the all-around strengthened public sphere.

In Thailand, the public has indeed capitalized on the advancement of information and communication technology (ICT) and its robust online sphere to enrich activism. The recent digital statistics from DataReportal (2022) reported that Thailand is one of the most socially and digitally-connected societies in Asia. As of the first quarter of 2022, about 78% of the Thai population have access to the internet and supposedly all of them are active social media users. The time that Thais spend online is also remarkable, averaging at 9 hours on the Web, and a little over 3 hours on social media daily (Leesa-nguansuk 2019). In the past decade, the country has experienced a series of protests and demonstrations for various socioeconomic and political issues. While goals of these movements vary, it is not surprising that the common denominator is the incorporation of social media platforms and applications into their operational strategy.

However, it appears that pro-democracy movement that was at the forefront of Thai political discussions since 2020 has yet to achieve any of its three key demands despite the innovative and creative strategies aided by ICT. This paper offers an analysis of this movement through the lens of rational choice approach. Specifically, I posit that there are, inter alia, three challenges that hamper the ability of the movement to gain sufficient momentum to reach the point where demands can be realized despite the use of social media as a part of its repertoire. These challenges, as will be discussed, are related to changes in the opportunity structure that ultimately conditions the effectiveness of social media and the internet as a “liberation technology (Diamond 2012, ix)” in the context of Thailand.

From rational choice’s perspective, there are several things that a person may consider upon deciding to join or not to join a movement. Since humans are intrinsically self-interested, rationality implies that they will not participate in a movement if they perceive that the chance of it achieving the goals is lower than the calculated risk–that is, if the costs are higher than the benefits brought about by the movement. The perception aspect of opportunity structure is also worthy of an emphasis since rational choice logic assumes that humans operate under informational uncertainty. Consequently, the decision whether to participate in a movement relies more on one’s subjective evaluation of the situation with a degree of uncertainty. A common question when people evaluate the opportunity structure is “what’s the probability of this movement being successful versus it being cracked down by the government?” and “what will I get from joining this movement?” While a number of scholars, such as Tilly, Tarrow, and McAdams (2004; 2007), have suggested ways that activists can enhance the likelihood of success through strategic planning, they also acknowledged that opportunity structure almost always defaults against the people due to the collective action problems that plague any social movements; including the new and digitized movements.

One: Strong Movement, Strong Government

In early 2020, when the pro-democracy movement was the most active, the government’s power and control was also at its peak. On one hand, the undercurrents of dissatisfaction among the youths toward the government had surfaced after the dissolution of the Future Forward Party, a party they perceived to be representative of not only the young generations, but also of liberal values. Shortly after the Supreme Court’s verdict, the movement took to the street and successfully brought out thousands to its earlier rallies. From Charles Tilly’s concept of WUNC (worthiness, unity, numbers, commitment), this movement had checked the boxes at least in the unity and numbers dimension; thus, should be able to leverage against the government to a certain degree. Why, then, did we not see that happening? The answer lies in the fact that the opportunity structure was still at its status quo–siding with the government by default. Having been elected only just a year before, General Prayuth Chan-ocha and his party, Palang Pracharat, were still able to maintain internal stability among its coalition. With support from allies and other state apparatus, the government was disinclined to listen to the movement’s demands and was much more resolved to crack down on protestors through both violent and legal means.

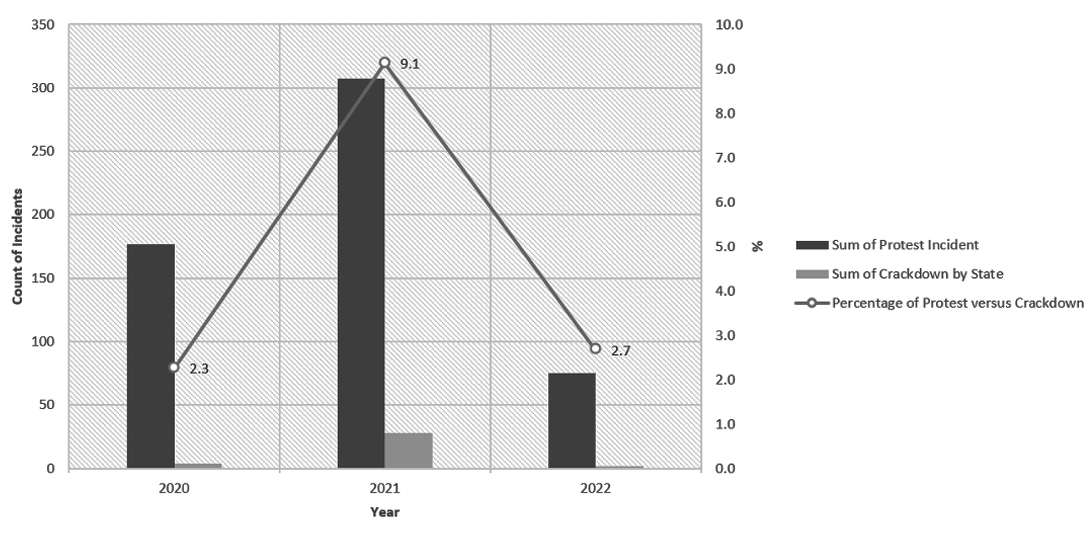

It is imperative to note that the default opportunity structure had in fact shifted unbeknownst to some as the ruling coalition was cracking from the inside out. I speculate that the decision of Palang Pracharat to boot Thammanat Phrompow and 20 other MPs in mid-January of 2022 signified the emerging political fault lines inside the government that slowly undermined its control and support from allies. However, the movement failed to capitalize on this shift due to several reasons such as the upswing of COVID-19 infections that inevitably led to a nationwide lockdown as well as many leading activists being arrested. Consequently, the movement lost its momentum simultaneously as the governing coalition weakened. This missed window of opportunity is also evident in my analysis of protest incident data recorded by iLaw. 1 It showed that from January 12, 2020 to October 3, 2022, 559 protests took place just in Bangkok alone. 2021 was the best performing year for the movement, reporting 307 gatherings in total–almost 55% of the total protest activities. Figure 1 below illustrates the locus of opportunity structure in which the pro-democracy movement seemed to be the most active when the government was also at its pinnacle of power (i.e., more inclined to crack down than to make a concession); and when the government’s influence gradually waned, the movement unfortunately also fizzled.

From the data, there were 34 incidents where law enforcement authorities forcefully put an end to the protest since 2020. Of course, the crackdowns happened most often in 2021 when the movement had the public attention, and the government was in control. However, they only did so twice in 2022, indicating the effect of the alleged gaping wound in the coalition on the opportunity structure.

Two: “Lost-and-leaderless” movement tactics

Time and time again, online activists have touted about their movements being horizontal, emphasizing on the notion that no one is the true leader. This feature, they believe, can make movements resilient to state repression just like the Arab Spring–a phenomenon that blazed through the Middle Eastern autocracies in 2011. However, revering upon the Arab Spring’s success has led many prospective pro-democracy movements astray as they became more focused on a short-term plan of mass mobilization than preparing their organizational capacity for long-term structural reforms. Chiefly using the Middle East in the 1o-year after the Arab Spring as an example, all the countries except for Tunisia, have reverted to some forms of authoritarianism. Why? In an op-ed on the New York Times, Tufekci (2022) acknowledged her misplaced hope on social media as an instrument for social movement that she made in her famous book, suggesting that while it is a wonderful tool for mobilization, social media cannot serve as an incubator of strong tie and commitment among protestors. Therefore, it produces only loose and leaderless movements, which are, for Gladwell (2011), not enough to create a revolution or fundamental changes.

As for Thailand, horizontal movement also proved to be a ludicrous concept; particularly, in setting the movement’s direction. On the get go, the movement consisted of smaller subsets with diverse agenda and priorities; for example, the LGBTQ+ and the feminists, whose focus is more on social and gender equality, and the college students from different universities who are more interested in the political issues. Despite them uniting under the three key demands later, the groups still occasionally organized events independently from each other. Moreover, since most of them are digital natives who can effectively use the technologies, the movement’s tactics are much more fluid (e.g., flash mobs that are organized only hours beforehand via Twitter, changing the venue last minute through Telegram, etc.) compared to previous movements. In one way, it is a good thing since they can evade the authorities relatively easier using digital technologies; thus, reducing the perceived risk in the opportunity structure. On the flipside, though, the fluidity of the tactics combined with the horizontal nature of the movement can be counterproductive; especially when some key activists have been arrested. 2 In some cases, more people would take to the street as they become enraged when seeing such abuses of power, but for the Thai pro-democracy movement, the arrests of key activists not only left the movement lost and leaderless in terms of direction, but also served as a scare tactic that fortified state’s opportunity structure. As a result, no activity of great magnitude or significance has occurred again since people like Penguin Cheewarak, Anon Nampa, Roong Panasaya got put in jail nor when they were released under the condition that they will not be participating in any protest again.

Three: Provocative demands are not always attractive demands

The final challenge faced by the youth-led movement is simple but very crucial to the propensity of success: the key demands especially the one about the monarchy. As we have established through rationality logic, there are already so many reasons that can dissuade someone from participation. Provocative demands can also be one of them as they do not get on well with the moderates, particularly in a chimeric society of pseudo-progressiveness like Thailand. Referring to Tilly’s WUNC concept aforementioned, one way that a movement can positively manipulate the opportunity structure is to find unity in numbers. However, when the movement proposed monarchical reform as one of its demands, it undermined the mobilization effort as it deterred many prospective joiners from joining the protest either due to fear or true disagreement. Pragmatically, it is necessary for the movement to appeal to a broader audience by modifying these demands. Ideologically, however, this option is understandably untenable.

In summary, the Thai public sphere has indeed benefitted from the existence of social media and ICT as they allow people to share ideas, express opinions, or even organizing protests with unprecedentedly fewer constraints than before. However, the propensity of success and the efficacy of such activism are not deterministic despite the use of social media as a mobilizing and coordinating platform. In fact, modern day’s movements still face a similar set of challenges that can be explained through classic frameworks in social movement study. For Thailand, the ebbs and flows of opportunity structure was left untapped by the youths as they faced challenges largely due to their operational strategy, leaving them in a perpetual struggle for democracy. That being said, the movement’s recent shift in narratives, focusing more on a call for elections, is a significant development. Not only that this is a sentiment that is already widely shared among the public, but also it is something that the government, with waning power at this point, see as an option with the lowest exit costs as well.

Surachanee “Hammerli” Sriyai

Surachanee “Hammerli” Sriyai is a lecturer and digital governance track lead at the School of Public Policy, Chiang Mai University.

Banner: October 2020, Bangkok, Thailand. Tens of thousands of pro democracy people gather to address various social problems, including government work problems, and criticize the monarch. Photo: kan Sangtong, Shutterstock

References

DataReportal. 2022. “Digital 2022: Thailand — DataReportal – Global Digital Insights.” Kepios. https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2022-thailand (June 14, 2022).

Diamond, Larry. 2012. Liberation Technology: Social Media and the Strugle for Democracy Introduction. eds. Larry Diamond and Marc F. Plattner. The Johns Hopkins University Press. https://books.google.com/books/about/Liberation_Technology.html?id=xhwFEF9HD2sC (December 14, 2022).

Gladwell, Malcolm. 2011. “From Innovation to Revolution-Do Social Media Made Protests Possible: An Absence of Evidence.” Foreign Affairs 90: 153.

Leesa-nguansuk, Suchit. 2019. “Thailand Tops Global Digital Rankings.” Bangkok Post. https://www.bangkokpost.com/tech/1631402/thailand-tops-global-digital-rankings (December 11, 2019).

McAdam, Doug, Sidney Tarrow, and Charles Tilly. 2004. Dynamics of Contention. Cambridge University Press.

Tarrow, Sidney, and Charles Tilly. 2007. The Oxford handbook of Comparative Politics Contentious Politics and Social Movements. Oxford University Press.

Tufekci, Zeynep. 2022. “I Was Wrong About Why Protests Work.” The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/07/21/opinion/zeynep-tufekci-protests.html.

Notes:

- I thank iLaw for generously sharing their data on protest incidents. iLaw is a Thai NGO which advocates for democracy, freedom of expression, and a fairer and more accountable system of justice in Thailand. ↩

- The fact that the government could target and arrest key activists also demonstrates the conceptual paradox of horizontal movement. ↩