The media frenzy blaming Joe Biden for the collapse of Afghanistan’s central government in August of 2021 puzzled me, as did repeated insinuations that the U.S. could have evacuated all Afghanis with pro-American sympathies or connections, an impossibility. The cynic in me figured that without Donald Trump and his Tweets to fill up air time, even moderate cable networks like CNN were overhyping stories like the return of the Taliban to keep their ratings up. In fact, the airlift out of Kabul was a tremendous accomplishment—the largest non-combat evacuation operation in U.S. military history thanks to the pilots and crew on U.S. Air Force transport aircraft carrying more than 79,000 civilians out of Afghanistan in just eighteen days.

My latest novel, In the Year of the Rabbit, takes place during the last three years of the Vietnam War. Vietnam itself was a mess. Cambodia, home of the infamous Killing Fields, was tragic. And Laos, where most of Year of the Rabbit takes place, was left in landlocked limbo, a wasteland, a bomb dump for U.S. military aircraft returning to Thai Air Force bases from missions over North and South Vietnam.

I first returned to Thailand in 1987 researching an earlier novel and beginning a twenty-year quest for a visa to enter Laos. I traveled extensively throughout Thailand, visiting ruins of Hindu Khmer temples at Phimai and Buriram and ancient capitals at Sukhothai and Ayutthaya, often eating and lodging with Thai families. Mostly, though, I stayed in Thai forest monasteries where I studied Vipassana meditation with Thai and Western Theravada monks, including several Americans who had once been soldiers. I began to see Vipassana as an answer to the personal anguish suffered by me and many of my fellow Vietnam-era veterans. And I saw Buddhism as a path to world peace that avoided the clash between Western communist and capitalist ideologies that had torn Southeast Asia asunder. My dream of world peace was shattered, however, by the events of 9/11/2001, which woke me up to the fact that the U.S. alone does not control the destiny of the world and that a much older cultural clash was still burning between Christianity and Islam, at least as far as Islamic fundamentalists in the Middle East were concerned.

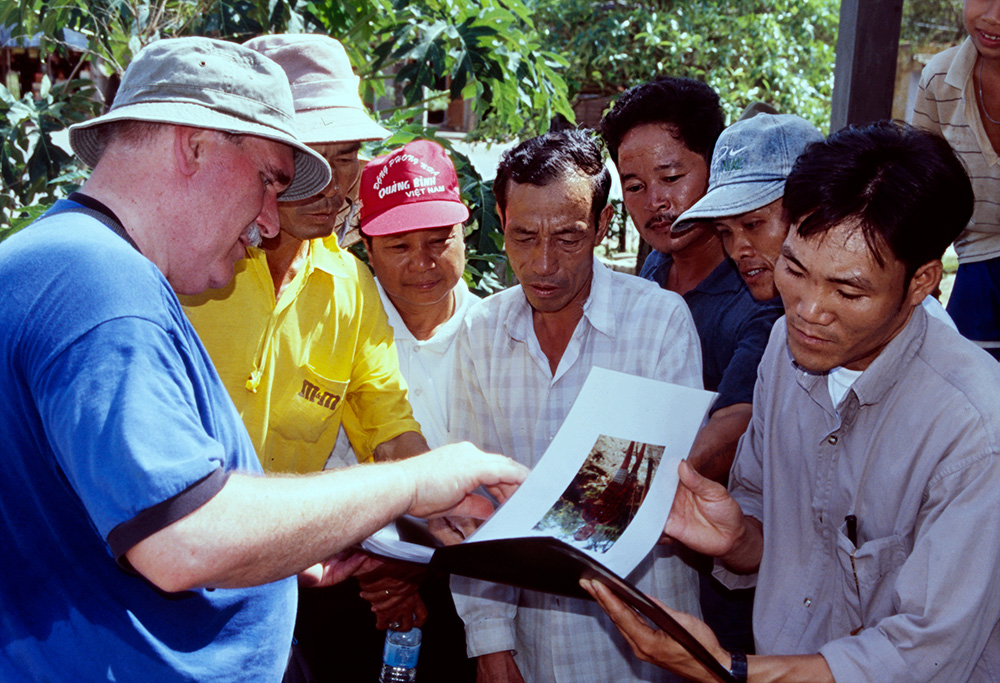

I finally got my Lao visa in 2005 and traveled through much of the country researching In the Year of the Rabbit. Thirty years after the war, roads were slow-going at best—full of pot holes and check points, often unpaved and overgrown with fresh stands of bamboo that needed to be cleared with the machetes my driver and I carried with us on the Toyota Landcruiser that we drove through the Annamite Mountains along the length of the Ho Chi Minh Trail from the old Pathet Lao capital of Sam Neua (just across the border from Dien Bien Phu, Vietnam) to Attapeu, a provincial capital in the South. I was shocked to see bridges the size of the famous Bridge on the River Kwai in Thailand that had been taken down by USAF fighter-bombers and—thirty years after the war—never repaired. Villagers were now forced to ford Mekong tributaries, but only during the months when the monsoon floods had receded.

I fear Afghanistan will share a similar fate, cut off from the world by the Taliban the way shell-shocked Laos was by its Pathet Lao government, one difference being that Lao women had served in the Pathet Lao’s revolutionary army, were receiving the same schooling as boys, and now worked as mechanics, drivers, bank and hotel managers and at any other job I saw a man working at. Then again, perhaps Laos with only three million inhabitants—a tenth that of Afghanistan—couldn’t afford the luxury of keeping half its population at home.

Laos in 1975 and Afghanistan today are what Thai street vendors call “same-same, only different.” They are both landlocked, mountainous, and poor. They both endured years of warfare that left both countries in economic ruin. And yet, unlike Laos, where tens of thousands of Hmong hilltribe fighters trained by the CIA were left to fend for themselves, tens of thousands of Afghans were expatriated, especially thanks to U.S. veterans who would not let their interpreters, their families, and other civilians who worked for the U.S. be abandoned. Then again, the Mekong River formed a porous border with Thailand that allowed a steady trickle of Hmong and other Laotians to escape over the next decade. The Hindu Kush Mountains, with peaks over 20,000 feet and passes more than 12,000 feet high (altitude sickness begins at 8,000 feet), form a daunting frontier with neighboring Pakistan for the city dwellers of Kabul who were left behind.

The U.S. Air Force motion picture units I served with were part of what was then the Military Airlift Command. I had left the Air Force only two years before the collapse of Southeast Asia to communist insurgencies. One of my most searing memories during those last few weeks was the Operation Babylift disaster—the crash of a C5-A, a giant cargo bird with 313 on board, into a rice paddy. Among the 114 who died were 78 orphans and two of my fellow USAF cameramen.

My last project before leaving the Air Force was a documentary on the rocky development of the C5. Pilots refused to use many of its “advanced” guidance systems (like one that supposedly permitted it to fly 50’ off the deck to avoid enemy radar). Wing cracks turned up in test and it failed to meet specs for short-field takeoffs and landings. Perhaps the most shocking scene I cut into the film was of Senator John Stennis, chair of the Senate Armed Services Committee, standing on the edge of the runway at Charleston Air Force Base, SC, extolling the virtues of the C5 as it rolled by behind him—followed a moment later by a runaway landing gear. Sadly, the losing bid to the Lockheed C5 Galaxy was the Boeing 747.

By contrast, the evacuation of Kabul, Afghanistan, was an astounding accomplishment. According to retired loadmaster Mike See, “The first C-17 evacuation flight from Kabul on Aug. 15, 2021, set a new record—by far—for the number of passengers carried on a Globemaster III at 823 people.” When a journalist asked the pilot if he really thought he could get off the ground so badly overloaded, the pilot answered, “Just watch me.”

Retired colonel Rob Rhyne flew two generations of Air Force cargo aircraft—the C5-B and the C-17, which he describes as superior in every way. He served several tours in Afghanistan as a C-17 aircraft commander, executive officer, and later as an advisor to General Petraeus. Now a Delta Airlines pilot, he reported to me that “in the first days of our evacuation efforts, as I sat on the tarmac at Dulles waiting for immigration officials to clear the 300 Afghan evacuees I flew out of Ramstein on my Airbus 350, I recalled how twenty years earlier I had been airdropping food and relief supplies to people who may now have been among my passengers. And I recalled a Christmas party at the embassy in Kabul where a 3-star British Army general proclaimed, ‘The goal of a war is to achieve a better peace’ and wondered if our ‘peace’ now would be any better in Afghanistan than it was before we started all this in 2001.”

When I arrived in Thailand in October of 1970 as a member of the 601st Photo Flight, we were briefed that we were being hosted by a constitutional monarchy—an Asian version of Great Britain, a worthy ally for idealistic young GIs eager to save the world from communism. “Same-same”—only very different, it turned out. In reality there had been as many coups as elections since the monarchy agreed to share power in 1932. And there had been no Winston Churchill inspiring the country to resist Japanese occupation during WW II. But I, like many GIs, was too enamored with Thai architecture, Thai food, and the fun-loving Thai people to pay much attention to Thai history and politics. It was my day job editing raw combat footage coming off of U.S. Air Force aircraft flying sorties all over Southeast Asia that had caught my full attention, an overuse of America’s destructive military power that haunts me to this day.

The U.S. employed a strategy of overkill that hearkened back to the American Civil War when artillery forged in Pittsburgh burned the cotton warehouses of Atlanta to the ground. In the jungles and rice paddies of Vietnam it was expressed as General Westmoreland’s “body counts.” From the air it took the form of deadly cluster bombs and napalm. Documenting the secret war in Laos, I saw more tonnage of bombs dropped on tiny, neutral Laos than were dropped worldwide in all of WW II. More than 100 sorties a day flew out of Ubon (one of five U.S. bases operating in Northeast Thailand), more sorites than the U.S. Army Air Corps and the RAF combined flew out of England over Germany.

The fall of South Vietnam to the North in April of 1975 was what caught the American public’s attention—because it had stopped paying attention once U.S. ground pounders had been pulled out under Nixon’s Vietnamization Program in the early 1970s and the dying turned over to the Vietnamese. The American air war continued unabated out of Thailand, however. Operation Pave Pronto, my primary assignment, was classified Top Secret and involved destroying North Vietnamese convoys along the Ho Chi Minh Trail in Laos, where both North Vietnam and the U.S. were abjectly ignoring the 1954 Geneva Accords that supposedly assured Laos’s neutrality.

Although there are more pages in American high school history books dedicated to the War of 1812 than to the Vietnam War, there is plenty of original source material available in print and video for anyone who wants to learn more about the U.S. failure in what was then called South Vietnam. But Vietnam is blessed with abundant natural resources and seaports and a communist regime that followed China’s lead and slowly opened itself up to free enterprise and world trade in the decades after the war.

It is what happened to Laos in its forgotten war that I fear is what will happen to Afghanistan. Both countries are “same-same” in many ways— both are landlocked and mountainous, the populations of both are impoverished and poorly educated, both have thrived at the crossroads of Asian trading caravans only to be transmuted by centuries of war, and both have only existed as countries over the past century or two.

Both countries paid dearly for muddled U.S. strategy—in Laos where the U.S. undermined neutralists like Souvanna Phouma and the brilliant Captain Kong Le while supporting tough-talking royalists who never fought but were happy to pocket American aid dollars. In Afghanistan we never sorted out who our friends were and who were playing us among Northern Alliance warlords and Karzai’s newly formed central government and military.

We missed opportunities early in both the Vietnam War and the War in Afghanistan to bring the conflicts to a quick end. In Vietnam we could have let national elections play out in 1956 as called for in the Geneva Accords. A worst-case Communist electoral victory would have spared Vietnam twenty years of war and millions of casualties. How had the U.S. failed to learn some humility from its defeat in Vietnam? How did hubris once again lead arrogant U.S. leaders to quash negotiations between Hamid Karzai’s central government and Mohammed Omar’s Taliban that had begun shortly after 9/11? I wish I had an answer.

Both countries were devastated by U.S. intervention while the elites in both countries grew rich from U.S. aid that failed to trickle down to the people who needed it most. And maybe most hauntingly same-same—both countries became the centers of world opium production while the U.S. was at war there, sending kilos of heroin back to the streets of Europe and to American cities. Ahmed Karzai, brother of Afghanistan’s first president, was thought to be a major player in the opium trade until he was assassinated in 2011. While the U.S. fought a futile battle to eliminate opium production, which corrupt warlords and government officials both used for self-enrichment, it was the Taliban alone that cut opium production radically in the few years it was in control.

A big question today is if the U.S. will be able to establish any kind of diplomatic relations with the Taliban, who desperately need aid for their war-torn country. China’s Belt and Road Initiative is a mixed blessing that does as much to enrich China economically and militarily as it does to develop the countries it is supposedly helping. In Afghanistan’s case, however, located as it is in the heart of Central Asia where it once thrived from the caravans traversing the ancient Silk Roads between China and Europe, the possibility of economic development that doesn’t involve opium cultivation is real.

Laos today is one of the last remaining socialist states in the world, its government dominated by the political arm of the Pathet Lao while other parties are banned. Meanwhile, the people of Laos remain desperately poor, with two thirds living below the international poverty line. The old French-built infrastructure running north to south remains in ruins. Whatever development has arisen since the Vietnam War runs east to west across the Mekong River over Friendship Bridges funded with Australian and Japanese investment that connect resource-rich Laos and baht-rich Thailand. Unlike Afghanistan, the American embassy in Vientiane continued to operate during and after 1975, permitting Lao-U.S. cooperation searching for the remains of missing U.S. airmen and clearing unexploded ordnance.

Since Vietnam, it’s been popular for U.S. leadership to proclaim, “We are not nation-building.” Paradoxically—the U.S. did some highly successful nation-building out of the ashes of WW II in Japan and Germany. Was that due to the administrative genius of General MacArthur in Japan and Marshall in Europe? Had we actually learned from the mistakes of the Treaty of Versailles, not extracting reparations as European victors did after WW I and instead rebuilding our former enemies into economically healthy democracies? Or was the lesson the U.S. and its Axis enemies learned from WW II to never again wage war on well-fortified beachheads like Normandy and hopping from island to bloody island in the South Pacific? Or was it perhaps both? In any case, Western democratic leaders committed deeply to a new world order based on trade and economic development.

Tragically, those lessons were lost by the time we entered what President Obama called “wars of choice.” With the development of the M16 and the AK-47, every modern infantryman carried a machine gun. A fighter-bomber like the F-4 Phantom with a crew of two carried three times as much payload as a WW II-vintage B-24 with a crew of eleven. A single B-52 could carpet bomb an entire NVA light division into oblivion. In Afghanistan the war has been closed off to reporters, so it will take years to figure out how much damage was inflicted by U.S. Air Force and Navy close air support—on combatants and civilians alike.

Today, in the middle East and elsewhere in the developing world, corrupt leaders have learned one valuable lesson from Vietnam: that U.S. aid money can be easily diverted. And perhaps a corollary the world has learned since the Vietnam War is that the U.S. is an unreliable ally. Trump abandoned the Kurds in Syria and set the stage for the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan. But that shouldn’t have been surprising after we abandoned Southeast Asia in 1975, leaving Hmong behind in the hills of Laos and leaving thousands of Vietnamese and Cambodians to fend for themselves. I’m reminded of the contractors from Voice of America I met in Udorn, Thailand in 1987. I had been invited up in the control tower because I had served with the USAF in Ubon—another provincial capital in remote Northeast Thailand—and the traffic controllers had fond memories of being trained by their U.S. Air Force counterparts. The contractors were proud to be boosting the power on Voice of America to reach deep into China. And it seemed to be effective two years later when a pro-democracy movement broke out, only to be crushed at Tiananmen Square while the U.S. stood by.

When I began researching the Vietnam War, trying to make sense of what I had seen and experienced during my tour, I developed a theory that the scale of war seemed to be shrinking since the great world wars of the Twentieth Century. Hadn’t almost as many Allied troops died in the Normandie Invasion from June 6 to August 21, 1944 (53,000 infantry and airmen) as all of the Americans killed in nearly twenty years in Vietnam—58,000? The catch is, we don’t know the total of U.S. allies (South Vietnamese, Koreans, Aussies, and civilians) who died in Southeast Asia. Estimates range from 400,000 to over a million. North Vietnamese, Lao and Khmer military and civilian deaths may have surpassed two million. The reality turns out to be that American casualties are going down (4,500 killed in Iraq, 2,400 in Afghanistan). But with a reliance on U.S. tactical air support and drones in the Middle East, the U.S. military really has no idea how many enemy combatants and civilians were killed. For civilians alone, estimates in Afghanistan range from 45,000-160,000. For Iraq: 100,000 to 600,000.

My personal lessons: it’s easy to get into a war, but hard to get out. And in war there really is no winner. I wish the British 3-star were right, that “the goal of a war is to achieve a better peace.” That was certainly the case with Europe and Japan after WW II. But even Dwight Eisenhower, commander of those victorious Allied forces, went on to say, “I hate war as only a soldier who has lived it can, only as one who has seen its brutality, its futility, its stupidity.” And yet today Russian troops mass on the eastern border of Ukraine. China pushes its way into Southeast Asia and the South China Sea, North Korea and Iran have gone rogue nuclear. Terrorist groups abound in the Middle East and Africa. A home-grown variety is spreading across the U.S. itself, twisted with logic that they are true patriots saving the country by destroying democracy.

And so the answer is complex—skillful diplomacy, good intelligence, thriving world trade that spreads prosperity, military readiness. And perhaps something new—random acts of kindness. Many random acts of kindness, like I experienced as a backpacker returning to Thailand in 1987 when I was invited to join family picnics after asking in broken Thai if I could take their picture or when I was taken home for dinner after bathing in the Chao Phraya River with young students who were eager to practice their English. At a government-to-government level it could take the form of aid to education, medicine, and infrastructure—without the strings that China attaches.

Unlike Vietnam, Laos, and Iraq, there was a reason—beyond ideology—to go to war in Afghanistan. Al-Qaeda had attacked the World Trade Center. And Al Qaeda lived and trained in Afghanistan under the protection of the ruling Taliban. But our downsized modern military, which doesn’t hesitate to call up Reserves and National Guard units—a taboo during the Vietnam era—has demanded multiple deployments by many of our troops—another taboo—taking a huge physical and emotional toll on our soldiers and their families, even the soldiers who come back without visible scars.

Part of the emotional healing process for many Vietnam-era veterans has been returning to Southeast Asia, sometimes making their own separate peace but sometimes meeting with their former enemies and sharing a mutual respect for the sacrifices made on both sides. Reconciliation has been possible in Southeast Asia because it was a war within, between quasi-democratic communist nationalists on one side and a quasi-democratic mix of royalist and free-enterprise capitalist nationalists on the other. Although slower coming to Laos than Vietnam, reconciliation was also due at least in part to Taoist and Buddhist culture being historically apolitical and non-proselytizing. I can still remember vividly the Royal Lao Major I met in Nong Kai in 1987 who had just been released after ten years in Pathet Lao reeducation camps. His eyes were haunted, but he had been released and allowed to join his exiled family that had been waiting for him in a Thai refugee camp.

I can’t imagine the Taliban releasing an officer who had worked for the U.S. or Karzai’s central government. I hope I’m wrong, but I am afraid this won’t be possible in Afghanistan, where vendettas can smolder for centuries. Islamic jihadists are deeply political, turning their backs on all things Western. The Taliban’s ideology, an oppressive combination of fundamentalist Sharia Law and ancient Pashtun tribal codes, was the ideology Mohamed Omar used twenty years ago to justify destroying the majestic Buddhas of Bamiyan, world cultural treasures carved into rock caves not far from Silk Road trade routes in the 6th and 7th centuries— because they were “idols.” It’s an ideology that today continues to justify denying Afghan women education and careers taken for granted in the developed world.

I hope that change is possible. The inevitability of change is a fundamental teaching of Buddhism. Perhaps it will come when hunger and poverty force the Taliban to give up beheadings and join the greater world as part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative. After all, it was only five hundred years ago that heads were still mounted on pikes on the road to London and two centuries ago that the French—the modern paradigm of civility and culture—were beheading fallen aristocrats on the guillotine. To Blacks living in the American Deep South a century ago during the age of Jim Crow when lynchings were all too common, the future looked grim, but in the words of the late Sam Cooke, “It took a long time comin’, but change is gonna come—oh yes, it will.”

Terence A. Harkin

Terence A. Harkin was awarded the 2020 Silver Medal in Literary Fiction from the Military Writers Society of America for his debut novel, The Big Buddha Bicycle Race. During the Vietnam War he served with the “Rat Pack,” the USAF photo unit operating out of Ubon, Thailand. He has returned often to Thailand and Laos.