Rodrigo Duterte’s tenure as President of the Philippines was nothing if not controversial. Whether in playing Beijing and Washington off one another, or in gauging how much savageness public opinion would tolerate in his drug war, Duterte often walked a tightrope in pursuit of his policy aims. One such balancing act which received comparatively minimal coverage during his tenure was Duterte’s relationship with international legal institutions.

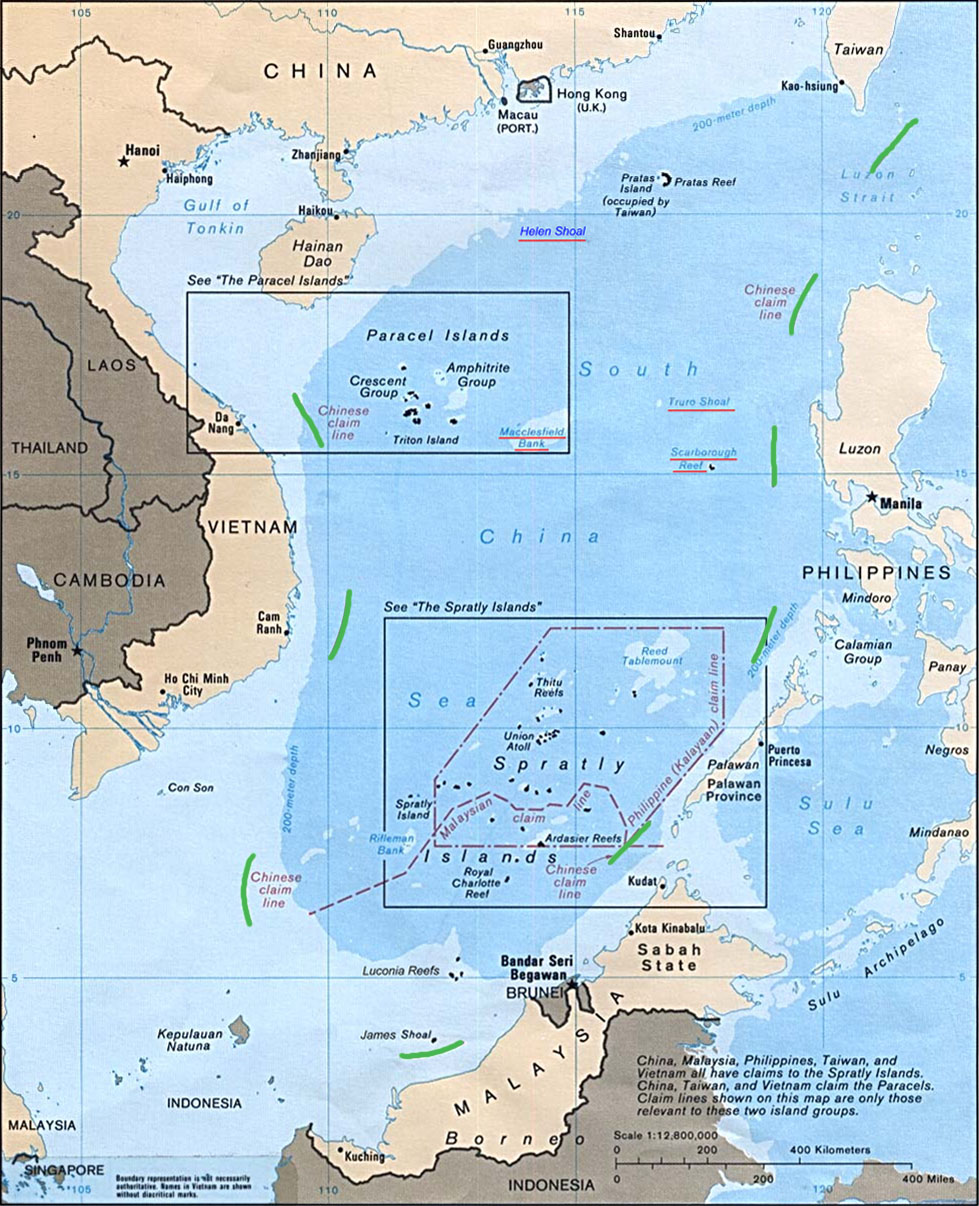

Conflict in the West Philippine Sea (or South China Sea, pick your poison) has often been considered an outgrowth of regional geopolitics, hinging on a number of different parties including the Philippines, PRC, US, ASEAN, etc. Yet the bedrock of contemporary arguments surrounding sovereignty over the Sea stems not from any of these parties directly, but from the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), as administered by the Permanent Court of Arbitration at the Hague.

Beginning in 2013 under President Benigno Aquino, the Philippines petitioned the court to challenge the PRC’s historic “nine dash line,” asserting that Chinese claims were meritless under UNCLOS. 1 After over three years of review the court decisively ruled in favor of the Philippines. However, during the course of the review process, Aquino reached his term limit and was succeeded by Rodrigo Duterte. In office only two weeks before the verdict was revealed, the new administration quickly back peddled from the court’s pronouncement, describing the ruling as “a piece of paper” and stating it would “take a back seat” in negotiations with the PRC. 2This was widely interpreted as an appeal to Chinese investment and protection, strengthening ties by refusing to assert Philippine sovereignty over the disputed territory.

There was more at play though–influence which had nothing to do with geopolitics and everything to do with Duterte’s own domestic policy and legacy. During his election campaign Duterte distinguished himself through his promise to violently purge the Philippines of drug use, elevating the issue from a peripheral topic to the main driver of the presidential campaign. 3 Upon assuming the presidency he sought to follow through on these promises, authorizing extrajudicial killings and other brutal means to prevent drug use, ultimately leading to over 9,000 deaths in his first year alone. 4 Both he and his administration knew that these actions would eventually attract the interest of the International Criminal Court. Quoted in 2017, an unnamed senior Western diplomat even stated in reference to Duterte and the ICC, “It may be the only thing he’s afraid of.” 5 The ICC gave Duterte more reason for apprehension in 2018 when they began a preliminary examination of the government’s drug war. 6 Duterte pushed back by withdrawing from the ICC, although the court retained jurisdiction over actions taken between 2011 and 2019.

Given these two unconnected interjections of international law into Philippine politics, Duterte faced a dilemma: how to effectively use the legal weight of the arbitral award as a bargaining chip with China while simultaneously discrediting the legitimacy of international law in ICC’s drug war investigation? For the first four years of his presidency, while he pursued closer ties with China, asserting the arbitral award was not a major priority, allowing Duterte to criticize both the award and the ICC investigation. However, as the Philippines drifted closer to the US, and public opinion grew more wary of China, Duterte experienced increasing pressure to assert the award. 7

This prompted a shift in policy, as Duterte could no longer afford a blanket rejection of international law and was thus forced to walk a thin line between observing UNCLOS and discrediting the ICC. In September of 2020 and 2021 Duterte used the UN General Assembly as an opportunity to emphasize the importance of the arbitral award, calling it a “triumph of reason over rashness, of law over disorder, of amity over ambition.” 8 In contrast, on the domestic stage Duterte continued to minimize the importance of the award, stating in a national broadcast in May 2021, “I’ll tell you son of a bitch, it’s just a piece of paper. I’ll throw that in the wastebasket.” 9

Based upon these vastly different approaches to discussing the arbitral ruling at home and abroad, the administration seems to have reasoned that the issue of sovereignty in the West Philippine Sea would be decided internationally, and therefore only by supporting the award on the world stage could the Philippines enforce its claim. Conversely, the administration was aware that for the ICC investigation to progress to trial, the government of the Philippines itself would have to authorize ICC access to witnesses and evidentiary materials. Thus, by disparaging the ICC and denigrating the arbitral award as merely a piece of paper to a domestic audience, Duterte could plant the seed that international legal mechanisms have no real power in the Philippines. The administration hoped that this message would have lasting effects on public opinion, making it politically impossible for Duterte’s successor—now President Bongbong Marcos—to cooperate with the ICC investigation, thereby insulating Duterte from any potential consequences.

This evidence indicates that while international media and policy makers considered Duterte’s drug war and the West Philippine Sea virtually unrelated topics, the presence of international legal institutions in both policy areas bound these issues together in the mind of Duterte and of those around him. Try as he might, Duterte could not discredit these institutions on an international stage while asserting the arbitral award. Likewise, he could not acknowledge the authority of international law on a domestic level for fear his successor would comply with the ICC and allow the investigation against him to progress. While many pinned Duterte’s vacillating approach to the West Philippine Sea simply as an outgrowth of tumultuous relations with China, it is impossible to dismiss the integral role of international justice and Duterte’s fear of the ICC in explaining his reticence to accept the arbitral award and acknowledge the legitimacy of international legal institutions.

Epilogue

Since the initial drafting of this article nearly one year ago, the situation has progressed significantly. Under President Marcos the Philippines has shifted to a kinder, friendly drug war that “pioneers a different approach,” 10 with Marcos stating,“I think we have found… that enforcement, which has been the part of the drug war that has been most vigorously pursued by President Duterte, only gets you so far.” 11 Meanwhile, Marcos has quietly rebutted the continued ICC investigation into Duterte, a position which has elicited only limited public outcry or backlash. 12 Marcos has also engaged in a fairly balanced foreign policy, continuing to play the US and China off one another, strongly asserting the arbitral award while also using it as a position of strength from which to negotiate. 13

From this long progression there are two lasting takeaways. First, by working to delegitimize the ICC within the Philippines and promote the succession of authoritarians like Marcos and his own daughter, Duterte has helped to ensure his legacy and avoid international punishment. Second, while fear of legitimizing the ICC may have impeded Duterte’s ability to emphasize the arbitral award, Marcos does not possess these concerns to the same degree and will therefore have a freer hand in negotiations with the PRC.

Zach Willis

Initially Written 12/21, Updated 11/22

Zach Willis is a recent graduate of Grinnell College specializing in International Relations and East Asian Studies. He is a former Political Intern at the U.S. Embassy in Manila and currently works for the Bulan Institute for Peace Innovations in Geneva. The ideas expressed here are his alone and do not represent the official position of any affiliated organization.

Zach Willis—Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia, Issue 33, Trendsetters, Feburary 2023

Reference

Cupin, Bea. “Marcos: Drug War Continues but ‘Slightly Different.'” Rappler (Manila, Philippines), September 24, 2022. Accessed November 28, 2022. https://www.rappler.com/nation/marcos-drug-war-continues-but-slightly-different/.

Grossman, Derek. “Duterte’s Dalliance with China is Over.” RAND. Last modified November 2, 2021. Accessed December 14, 2021. https://www.rand.org/blog/2021/11/dutertes-dalliance-with-china-is-over.html

Hillebrecht, Courtney. “The ICC case against Duterte’s drug war is on hold. That could hurt the court’s authority.” The Washington Post (Washington, DC), December 6, 2021. Accessed December 25, 2021. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2021/12/06/icc-case-against-dutertes-drug-war-is-hold-that-could-hurt-courts-authority/.

Kabiling, Genalyn. “Duterte raises PH arbitral win at UN.” Manila Bulletin (Manila, Philippines), September 23, 2020. Accessed December 19, 2021. https://mb.com.ph/2020/09/23/duterte-raises-ph-arbitral-win-at-un/.

Lim, Benjamin Kang. “Philippines’ Duterte says South China Sea arbitration case to take ‘back seat.” Reuters. Last modified October 19, 2016. Accessed December 27, 2021. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-philippines/philippines-duterte-says-south-china-sea-arbitration-case-to-take-back-seat-idUSKCN12J10S.

Manhit, Victor. “8/10/2021 Political Briefing.” Speech, Stratbase, August 10, 2021.

Mercado, Neil Arwin. “Duterte on PH court win over China: ‘That’s just paper; I’ll throw that in the wastebasket.” Inquirer (Manila, Philippines), May 6, 2021. Accessed December 26, 2021. https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1427860/duterte-on-ph-arbitral-win-over-china-papel-lang-yan-itatapon-ko-yan-sa-waste-basket.

Ong, Ghio. “‘Drug War under Marcos to Heed Legal Framework.'” Philstar (Manila, Philippines), November 26, 2022. Accessed November 28, 2022. https://www.philstar.com/headlines/2022/11/26/2226517/drug-war-under-marcos-heed-legal-framework.

Permanent Court of Arbitration. “The South China Sea Arbitration (The Republic of Philippines v. The People’s Republic of China).” PCA-CPA.org. Accessed December 26, 2021. https://pca-cpa.org/en/cases/7/.

Rauhala, Emily. “Duterte says the International Criminal Court doesn’t worry him.” Washington Post (Washington, DC), June 4, 2017, Asia and Pacific. Accessed December 27, 2021. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/duterte-says-the-international-criminal-court-doesnt-worry-him/2017/06/03/8a8f0c62-44d6-11e7-b08b-1818ab401a7f_story.html?itid=lk_inline_manual_15.

Wong, Andrea. “ICC Pushes Probe on the Philippines’ Drug War.” The Interpreter. Last modified August 9, 2022. Accessed November 28, 2022. https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/icc-pushes-probe-philippines-drug-war.

Zhen, Liu, and Amber Wang. “China-Philippines Relations: Marcos Looks to Beijing Visit, Expanding Ties after Meeting Xi Jinping on Apec Sidelines.” South China Morning Post, November 18, 2022. Accessed November 28, 2022. https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3200062/china-philippines-relations-marcos-looks-beijing-visit-expanding-ties-after-meeting-xi-jinping-apec.

Notes:

- The Permanent Court of Arbitration, “The South China Sea Arbitration (The Republic of Philippines v. The People’s Republic of China),” PCA-CPA.org, accessed December 26, 2021, https://pca-cpa.org/en/cases/7/ ↩

- Benjamin Kang Lim, “Philippines’ Duterte says South China Sea arbitration case to take ‘back seat,” Reuters, last modified October 19, 2016, accessed December 27, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-philippines/philippines-duterte-says-south-china-sea-arbitration-case-to-take-back-seat-idUSKCN12J10S ↩

- Victor Manhit, “8/10/2021 Political Briefing” (speech, Stratbase, August 10, 2021). ↩

- Emily Rauhala, “Duterte says the International Criminal Court doesn’t worry him,” Washington Post (Washington, DC), June 4, 2017, Asia and Pacific, accessed December 21, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/duterte-says-the-international-criminal-court-doesnt-worry-him/2017/06/03/8a8f0c62-44d6-11e7-b08b-1818ab401a7f_story.html?itid=lk_inline_manual_15 ↩

- Emily Rauhala, “Duterte says the International Criminal Court doesn’t worry him,” Washington Post (Washington, DC), June 4, 2017, Asia and Pacific, accessed December 21, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/duterte-says-the-international-criminal-court-doesnt-worry-him/2017/06/03/8a8f0c62-44d6-11e7-b08b-1818ab401a7f_story.html?itid=lk_inline_manual_15 ↩

- Courtney Hillebrecht, “The ICC case against Duterte’s drug war is on hold. That could hurt the court’s authority.,” The Washington Post (Washington, DC), December 6, 2021, accessed December 25, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2021/12/06/icc-case-against-dutertes-drug-war-is-hold-that-could-hurt-courts-authority/ ↩

- Derek Grossman, “Duterte’s Dalliance with China is Over,” RAND, last modified November 2, 2021, accessed December 14, 2021, https://www.rand.org/blog/2021/11/dutertes-dalliance-with-china-is-over.html ↩

- Genalyn Kabiling, “Duterte raises PH arbitral win at UN,” Manila Bulletin (Manila, Philippines), September 23, 2020, accessed December 19, 2021, https://mb.com.ph/2020/09/23/duterte-raises-ph-arbitral-win-at-un/ ↩

- Neil Arwin Mercado, “Duterte on PH court win over China: ‘That’s just paper; I’ll throw that in the wastebasket,” Inquirer (Manila, Philippines), May 6, 2021, accessed December 26, 2021, https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1427860/duterte-on-ph-arbitral-win-over-china-papel-lang-yan-itatapon-ko-yan-sa-waste-basket ↩

- Ghio Ong, “‘Drug War under Marcos to Heed Legal Framework,’” Philstar (Manila, Philippines), November 26, 2022, accessed November 28, 2022, https://www.philstar.com/headlines/2022/11/26/2226517/drug-war-under-marcos-heed-legal-framework ↩

- Bea Cupin, “Marcos: Drug War Continues but ‘Slightly Different,’” Rappler (Manila, Philippines), September 24, 2022, accessed November 28, 2022, https://www.rappler.com/nation/marcos-drug-war-continues-but-slightly-different/ ↩

- Andrea Wong, “ICC Pushes Probe on the Philippines’ Drug War,” The Interpreter, last modified August 9, 2022, accessed November 28, 2022, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/icc-pushes-probe-philippines-drug-war ↩

- Liu Zhen and Amber Wang, “China-Philippines Relations: Marcos Looks to Beijing Visit, Expanding Ties after Meeting Xi Jinping on Apec Sidelines,” South China Morning Post, November 18, 2022, accessed November 28, 2022, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3200062/china-philippines-relations-marcos-looks-beijing-visit-expanding-ties-after-meeting-xi-jinping-apec ↩