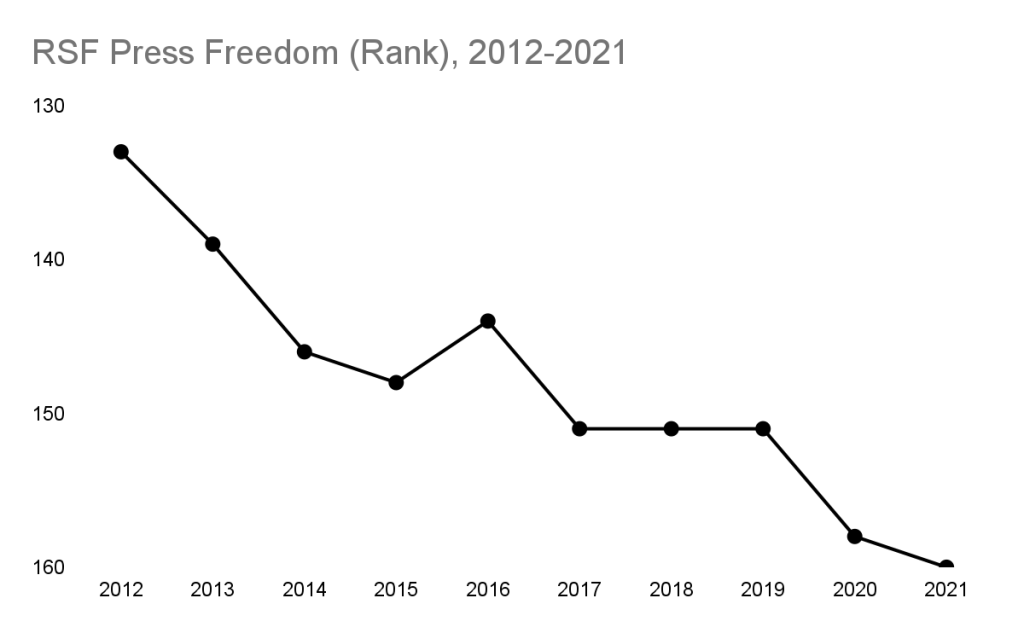

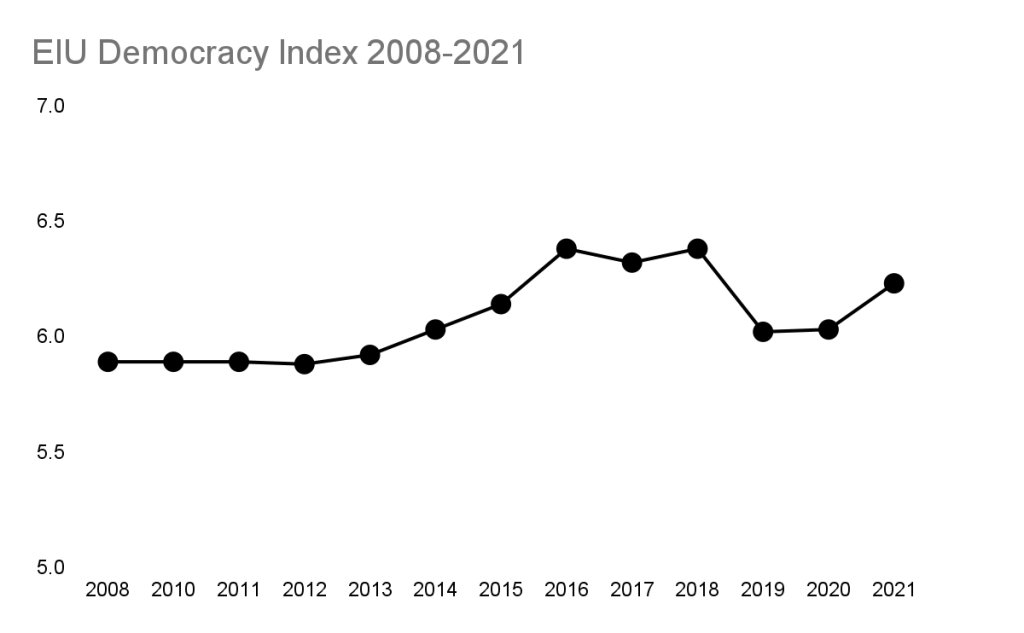

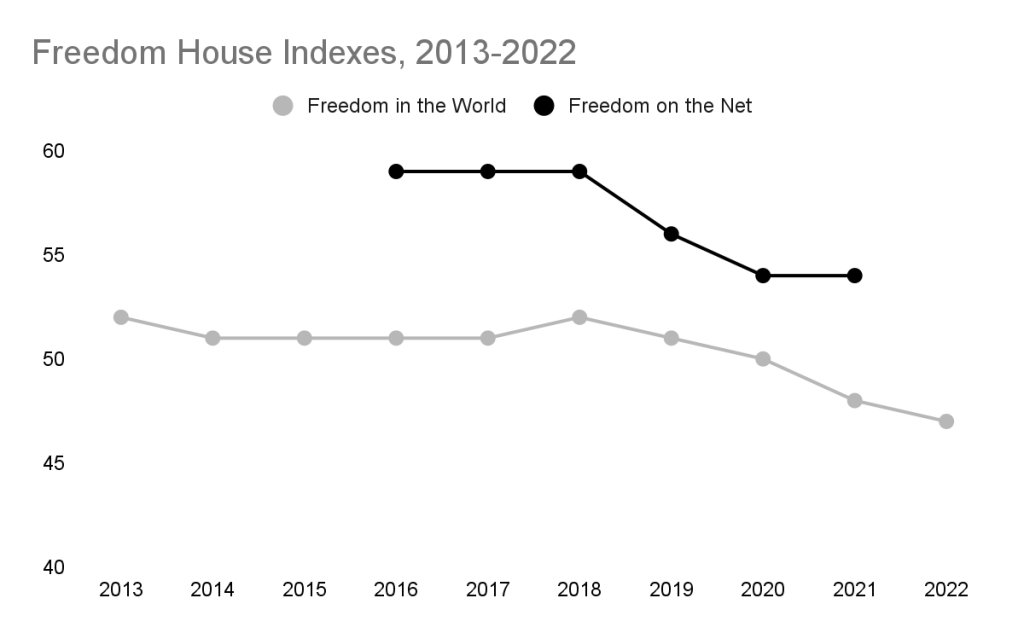

Singapore has effectively been a one-party state, with the People’s Action Party (PAP) at the helm, since the country’s first post-independence parliamentary election in 1968. Freedom House has consistently ranked the city-state as ‘partly free’ since its first situation report in 1973. 1 From 2006 to 2013, the Economist’s Intelligence Unit described Singapore as a ‘hybrid regime’, and later as a ‘flawed democracy’ (2014 to 2021). 2 Press freedom is severely restricted, with Reporters Without Borders (RSF) ranking Singapore, in its 2021 World Press Freedom Index, among the worst in the world at 160/180. 3

With the spread of internet connectivity from the late 1990s to the 2010s, the PAP administration and its affiliates have been finding it increasingly difficult to shape political narratives as the power and influence of the mainstream media has gone into decline. Due to this, the focus has shifted to combating alternative narratives online by introducing laws to regulate online content; the result of this is that internet freedoms and digital rights have declined and digital authoritarianism has been on the rise in recent years. A quantitative measure of this deterioration can be found in Freedom House’s ‘Freedom on the Net’ index, which had ranked the country at 59 out of 100 in 2016, and 54 out of 100 in 2021. 4

This article examines the current state of ‘digital authoritarianism’ in Singapore: the use of laws, surveillance by the state, and pro-PAP trolling to dominate discussions within the country’s digital sphere and to manipulate the flow of information to the city-state’s population. It argues that, while in the short term, it keeps political challengers in check, the pool of people affected by the PAP’s harsh measures has increased, and they have come to form the base of what might be a potential change of regime sometime in the future.

Developments in Digital Authoritarianism

The PAP administration’s enactment of new laws governing the digital realm are aimed at restricting online expression, which evolved during the unprecedented boom of social media in the late-2000s and throughout the 2010s. This period also saw the worst ever electoral performance of the PAP: the 2011 general election; 5 after which, such measures related to censorship and the flow of information were enhanced.

Table 1: Key Digital Legislation in Singapore

| Constitution | Parliament can impose restrictions as it considers necessary or expedient on the freedom of speech and expression for national security, friendly relations with other countries, public order, morality, to protect privileges of Parliament and against contempt of court, defamation or incitement to any offence. |

| Defamation | Definition: harming, with intention or having reason to believe that it will harm, a reputation of a person. ‘Harming of reputation’ is explained as an act of lowering the moral, intellectual character or merit of one, or causing it to be believed that the body of that person is loathsome or generally disgraceful. Punishment: imprisonment ≤ 2 yrs; fine; or both |

| IMDA Act | IMDA is given the following functions: promote the information, communications and media industry; regulate the telecommunication systems and services; ensure that the content is not against the public interest, public order or national harmony |

| Broadcasting Act | Gives power to IMDA to specify conditions for granting licences (Art. 5, 9) and demand any material intended for broadcasting (Art. 16, 17) |

| POFMA | Fine of ≤ 50,000 SGD (≤ 36,975 USD) for communicating falsehoods or statements that undermine the security of Singapore, diminish public confidence in Government, etc. ‘Directions’ can also be issued by government Ministers: Correction, Stop Communication, Disable Access, etc. Ministers can direct IMDA to order ISPs to disable access should they not comply with Direction notices. |

Central to digital content management in the city-state is the Infocomm Media Development Authority (IMDA), established after the 2015 election. 6 IMDA the result of an accumulation of new laws and regulations related to the media and the dissemination of information. For this reason, the authority was given overarching power to: specify conditions for granting broadcasting licences; 7 to take action with regard to the contents or programmes that are or will be broadcast (over the internet and social media); 8 and to arbitrate what content is deemed a threat to public order, social harmony and national security.

Ahead of the 2020 general election, the PAP administration further enacted the Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act (POFMA), which has become responsible for silencing critics and voices of dissent under the guise of managing ‘fake news’ in the country. The authoritarian nature of the law lies within the excessively harsh penalties for spreading fake news and half-truths, whether deliberate or not. This gives the PAP administration the power to manipulate the flow of information in their favour against non-Governmental actors that are in opposition to them. 9 Its staff are also given the inherently judicial function of interpreting which news is ‘fake’ and which is misleading. The ability to appeal to the court against POFMA orders is predicated on whether an appeal has been approved by the government or not.

The same argument that stability and harmony must be maintained at all costs, which justify the existence of IMDA and POFMA, is also used to justify mass surveillance. 10 Mass surveillance systems in place in Singapore are supported by the power of the executive, to assess and legally interpret threats to national security, and additionally by a lack of legal barriers to restrict abuse of this power. The omission of the right to privacy in the constitution, most critically, allows the government to sign-off on surveillance operations, without the need to obtain prior judicial authorisation.

While there are no official records of the extent of Singapore’s surveillance capabilities, the US State Department notes that Singapore has ‘extensive networks’ of ‘highly sophisticated capabilities [to] … conduct surveillance … [on] digital communications intended to remain private’. 11 For one, to curb the spread of COVID-19, the government introduced the ‘TraceTogether’ app for contact-tracing. In January 2021, it was announced that the database storing data in the app was readily accessible by the Singapore Police Force (SPF) for criminal investigations. 12 A bill to limit the use of such tracking capabilities by the police was only passed after many expressed concerns over mass surveillance in the country in 2021. 13

The use of surveillance capabilities, hacking tools, and spyware was also exposed by a document leaked by Edward Snowden, that claim that data from underwater internet cables that run from East Asia, through Singapore, to Europe was accessible to the authorities in Singapore. 14 In the same year, IMDA also appears to have been an active client of the infamous Italian hacking and surveillance firm, ‘Hacking Team’. 15 For its UPR submission in 2017, Privacy International also reported on the presence of ‘PacketShaper’, a system of surveillance and monitoring of encrypted content, that was being used in the country at that time. It also noted that the Singaporean state hosts a server for the malware system ‘Finspy’. 16 More recently, Reuters published a report in February 2022 that ‘QuaDream’, an Israeli-based developer of hacking tools was being employed by the Singaporean government. 17 The issue was brought to national attention when Workers’ Party chairperson Sylvia Lim claimed in a parliament session in February 2022 that Apple had notified her that her iPhone was subject to hacking by state-sponsored attackers. 18

Such capabilities are supported by physical surveillance infrastructure in the country, such as the 90,000 or more CCTV cameras in the country. The import of Chinese facial recognition cameras, embedded in lampposts across the city, are aimed to facilitate the creation of crowd analytics to assist with ‘anti-terror operations’. 19 This calls into question the extent to which the PAP administration is willing to invest in high-tech infrastructure to monitor its citizens; and also the extent to which it will cooperate with other authoritarians, such as China, to do so.

Targeting Civil Society and Opposition Parties

IMDA and the government-run fact-checking initiative under POFMA are known to target opposition figures and critics. 20 POFMA has, as of February 2022, been used on 13 separate occasions, being used to target non-PAP politicians, activists and human rights defenders, and online news platforms. 21 The campaign period for the 2020 general election saw a rise in the use of POFMA. 22 While POFMA does serve as an effective system for fact-checking and provides information to clarify misunderstandings about government policies, the practice of withholding information and the use of POFMA to take action against political opponents or media practitioners serve to institute a culture of self-censorship among those who criticise or oppose the PAP. 23

IMDA has also been active in targeting content and content creators it deems threatening to social harmony. In one case, it blocked a website hosting what it said was an unsubstantiated article about PM Lee Hsien Loong’s involvement in the 1MDB Scandal, for the reason that it undermined public confidence in the Singaporean government. 24 In July 2019, access was blocked to a protest rap video that criticised the treatment of minorities in the country. 25

IMDA has also used various other legislation in its arsenal. The Online Citizen, for example, had been continuously targeted by IMDA. In December 2018, it was notified that it could not receive donations from ‘unverified local sources’ through its subscription model and that it had to annually report its finances to IMDA as it ‘could be an avenue for foreign influence’. In 2021, IMDA had its license suspended. 26 Prior to this, IMDA filed a criminal defamation report against Terry Xu, the editor of the website, for posting an open letter by a reader in September 2018 claiming that there is ‘corruption at the highest echelons’ of the ruling party. 27 This report came after Xu had complied with IMDA’s take-down order and removed the post. Terry Xu and the author of the letter, Daniel De Costa Augustin, were later found guilty of defamation in November 2021. 28 During the trial, the prosecutor maintained that the act was undertaken with a malicious intent to harm the reputation of the government. 29

The PAP administration has also made requests to Meta (Facebook) for user data, averaging 1500 requests per year in the past three years, higher than the global average of 1100 requests, and more than all requests from the rest of the Southeast Asian region combined. 30 Although to a much lesser extent than Facebook, Twitter, 31 Microsoft, 32 and Google 33 are also regularly requested for information by the Singaporean government.

While these companies had previously been quiet in their criticism, their concerns were articulated during the passing of POFMA. Google stated that the law would hurt innovation and the growth of the country’s digital information ecosystem. Facebook reminded the PAP administration of its promise that there will be a proportionate and measured approach to the use of POFMA. 34 However, after it was legally compelled to block access to the State Times’ Review under POFMA orders, Facebook expressed its dissatisfaction with the law, stating that the measures were disproportionate and that POFMA was being used as a censorship tool. 35

Although the government claims to promote such high ideals as ‘truth’ and ‘social harmony’, the PAP administration looks the other way when their supporters and pro-PAP trolls deliberately spread misleading or false information in favour of the government. These so-called ‘Internet Brigades (IBs)’ are part of the administration’s cyber-strategy for dealing with critics online, using the justification that it was necessary for the party to have a voice within the anti-establishment cyberspace. 36

In June 2020, Facebook took down a pro-PAP Facebook page ‘Fabrications About the PAP’ (250,000 followers), which had been set up as a response to anti-government websites. 37 Nevertheless, another ‘Fabrications About the PAP’ Facebook page was set up and has amassed around 5,500 followers since. This page is still regularly posting pro-PAP updates and videos, with many critics pointing out that some of its contents are false. 38

Singapore Matters 39 is another platform that promotes members of the PAP administration and regurgitates the mainstream media’s negative framing of members of civil society, independent online media, and opposition parties. These pages have neither been blocked under POFMA for false statements, nor have the owners of these pages been charged with harassment under information or media laws managed by IMDA.

Conclusion

POFMA, laws under the management of IMDA, and other laws, help the PAP constrain the internet and social media platforms from serving as a platform for counter-narratives. Additionally, these laws and institutions prevent challenges to the PAP’s negative framing of civil society, independent online media and opposition parties. At the same time, both the PAP and its supporters have also taken to the internet and social media platforms to set up websites and social media accounts to cause reputation damage to their political opponents. The threat to democratic development under the PAP’s administration is real in the city-state, however, the number of alternative actors has increased over the last decade or so. The continuous harassment and persecution of civil society, independent online media, and opposition parties, has led to the expansion and strengthening of the pool of challengers. Hence, in spite of the rise of digital authoritarianism in Singapore, the foundations of an alliance to challenge the PAP regime have been laid and are set to grow in Singapore.

James Gomez

Regional Director at Asia Centre

Banner: Singapore, May 2022. A circle of 6 cameras CCTV outside a building in Singapore. Bima Eriarha, Shutterstock

Notes:

- Freedom House, ‘Freedom in the World’, Freedom House, 2022, https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world. ↩

- Economist Intelligence Unit, Democracy Index 2021: The China Challenge (Economist Intelligence Unit, 2022), https://www.eiu.com/n/campaigns/democracy-index-2021 ↩

- RSF ‘2021 World Press Freedom Index: Singapore’, Reporters Without Borders, 2011, https://rsf.org/en/ranking ↩

- Freedom House, ‘Freedom on the Net’, Freedom House, 2022, https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-net ↩

- Institute of Policy Studies, Singapore, ‘POPS (5) Presidential Election Survey 2011’, Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, 2011, https://lkyspp.nus.edu.sg/docs/default-source/ips/pops-5_slides_0911.pdf ↩

- IMDA was created as a restructuring and merger of the Infocomm Development Authority (IDA) and Media Development Authority (MDA) ↩

- Law Revision Commission, ‘Info-Communications Media Development Authority Act 2016’, Singapore’s Attorney-General’s Chamber, 1 April 2022, https://sso.agc.gov.sg/Act/IMDAA2016 ↩

- Law Revision Commission, ‘Broadcasting Act 1994’, Singapore’s Attorney-General’s Chamber, 18 April 2022, https://sso.agc.gov.sg/Act/BA1994 ↩

- Aqil Haziq Mahmud and Tang See Kit (2019) ‘“Very onerous” process to challenge order on content deemed as online falsehood: Sylvia Lim’, Channel News Asia, 8 May 2019, https://www.channelnewsasia.com/singapore/online-falsehoods-bill-workers-party-onerous-appeal-process-877101 ↩

- Shane Harris, ‘The Social Laboratory’, Foreign Policy, 29 July 2014, https://foreignpolicy.com/2014/07/29/the-social-laboratory ↩

- Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor, Singapore 2015 Human Rights Report (United States Department of State, 2015), 8, https://2009-2017.state.gov/documents/organization/253009.pdf ↩

- Matthew Mohan, ‘Singapore Police Force can obtain TraceTogether data for criminal investigations: Desmond Tan’, Channel News Asia, 4 January 2021, https://www.channelnewsasia.com/singapore/singapore-police-force-can-obtain-tracetogether-data-covid-19-384316 ↩

- Kenny Chee, ‘Bill limiting police use of TraceTogether data to serious crimes passed’, The Straits Times, 2 February 2021, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/politics/bill-limiting-use-of-tracetogether-for-serious-crimes-passed-with-govt-assurances ↩

- Philip Dorling, ‘Singapore, South Korea revealed as Five Eyes spying partners’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 25 November 2013, https://www.smh.com.au/technology/singapore-south-korea-revealed-as-five-eyes-spying-partners-20131124-2y433.html ↩

- Ibid.; Jeanette Tan,‘ Does Italian surveillance tech firm Hacking Team sell spy software to Singapore’s IDA?’ Mothership, 7 July 2015, https://mothership.sg/2015/07/does-italian-surveillance-tech-firm-hacking-team-sell-spy-software-to-singapores-ida ↩

- Privacy International, Universal Periodic Review Stakeholder Report: 24th Session, Singapore: The Right to Privacy in Singapore (Privacy International, 2017), https://privacyinternational.org/sites/default/files/2017-12/Singapore_UPR_PI_submission_FINAL.pdf ↩

- Ibid.; Christopher Bing and Raphael Satter, ‘EXCLUSIVE iPhone flaw exploited by second Israeli spy firm-sources’, Reuters, 3 February 2022, https://www.reuters.com/technology/exclusive-iphone-flaw-exploited-by-second-israeli-spy-firm-sources-2022-02-03 ↩

- Kenny Chee, ‘WP chairman Sylvia Lim’s phone not hacked by Singapore Govt: Shanmugam’, 19 February 2022, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/politics/wp-chairman-sylvia-lims-phone-not-hacked-by-singapore-govt-shanmugam ↩

- Steven Feldstein, ‘The Road to Digital Unfreedom: How Artificial Intelligence is Reshaping Repression’, Journal of Democracy 30 (1) (January 2019): 40, https://carnegieendowment.org/files/201901-Feldstein-JournalOfDemocracy.pdf ↩

- Lasse Schuldt, ‘Official Truths in a War on Fake News: Governmental Fact-Checking in Malaysia, Singapore, and Thailand’, Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs 40(2) (2021): 340-371, DOI: 10.1177/18681034211008908 ↩

- Factually, ‘Factually: POFMA’, Government of Singapore, 2022, https://www.gov.sg/factually?topic=POFMA; POFMA’ed, ‘POFMA’ed Dataset’, POFMA’ed, 24 May 2021, https://pofmaed.com/data/ ↩

- POFMA’ed (2020) ‘Explainer: What is POFMA?’, POFMA’ed, at: http://pofmaed.com/explainer-what-is-pofma ↩

- See Schuldt, ‘Official Truths in a War on Fake News’. ↩

- Freedom House, ‘Freedom on the Net 2021: Singapore’. ↩

- Ng Huiwen, ‘Police looking into rap video by local YouTube star Preetipls alleged to contain offensive content’, The Straits Times, 30 July 2019, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/police-looking-into-rap-video-by-local-youtube-star-preetipls-allegedly-containing ↩

- Rei Kurohi, ‘The Online Citizen taken offline, ahead of deadline set by IMDA after failure to declare funding’, The Straits Times, 16 September 2021, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/the-online-citizen-goes-dark-ahead-of-deadline-set-by-imda; Palatino Mong, ‘Singapore’s The Online Citizen news website stops operating after government suspends its license’, The Straits Times, 18 September 2021,https://globalvoices.org/2021/09/18/singapores-the-online-citizen-news-website-stops-operating-after-government-suspends-its-license ↩

- ‘Why The Online Citizen is being investigated for ‘criminal defamation’, Coconuts Singapore, 21 November 2018, https://coconuts.co/singapore/news/online-citizen-investigated-criminal-defamation ↩

- In the same trial, Daniel De Costa Augustin was also convicted of a charge unauthorised access to an email account of an another individual he used to submit the letter. ↩

- Lydia Lam, ‘The Online Citizen’s Terry Xu and writer convicted of criminal defamation over article calling Cabinet corrupt’, Channel News Asia, 12 November 2021,https://www.channelnewsasia.com/singapore/online-citizen-toc-terry-xu-editor-writer-criminal-defamation-2308961 ↩

- ‘Government Requests for User Data’, Meta, 2022, www.transparency.fb.com/data/government-data-requests ↩

- ‘Information Requests’, Twitter, 2022, https://transparency.twitter.com/en/reports/information-requests.html ↩

- ‘Law Enforcement Requests Report’, Microsoft, 2021, https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/corporate-responsibility/law-enforcement-requests-report ↩

- Global Requests for User Information’, Google Transparency Report, 2021, https://transparencyreport.google.com/user-data/overview ↩

- Jewel Stolarchuk, ‘Google and Facebook remain concerned over Singapore’s newly-passed fake news law’, The Independent Singapore, 9 May 2019, https://theindependent.sg/google-and-facebook-remain-concerned-over-singapores-newly-passed-fake-news-law ↩

- Shawn Lim, ‘Facebook expresses censorship concerns after blocking Singapore users’ access to fake news page’, The Drum, 19 February 2020, https://www.thedrum.com/news/2020/02/19/facebook-expresses-censorship-concerns-after-blocking-singapore-users-access-fake ↩

- Lu Xueying, ‘PAP moves to counter criticism of party, Govt in cyberspace’, The Straits Times, 3 February 2007; https://bit.ly/36VmC0R; PAPBrigade, ‘About’, PAP Internet Brigade, 2012, https://papbrigade.tumblr.com/about ↩

- Aqil Haziq Mahmud, ‘Facebook removes Fabrications About The PAP admin accounts for violating policies’, Channel News Asia, 28 June 2020, https://www.channelnewsasia.com/singapore/facebook-removes-fabrications-about-the-pap-accounts-663871 ↩

- Suleiman Daud, ‘PAP GE 2020 candidate says people “misunderstood” why he shared unsubstantiated Fabrications About PAP post about Sarah Bagharib & WP’, Mothership, 18 June 2021, https://mothership.sg/2021/06/shamsul-kamar-sarah-bagharib ↩

- Singapore Matters has a Facebook page with over 85,000 likes and 97,000 followers. See “Singapore Matters”, Facebook, https://www.facebook.com/SingaporeMatters ↩