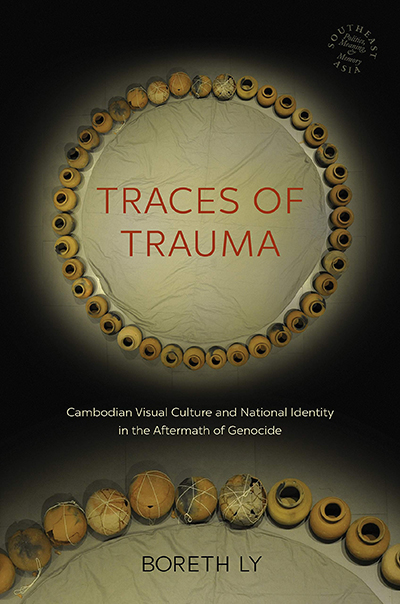

Title: Traces of Trauma: Cambodian Visual Culture and National Identity in the Aftermath of Genocide

Author: Boreth Ly

Publisher: University of Hawai’i Press, 2019

Boreth Ly’s Traces of Trauma: Cambodian Visual Culture and National Identity in the Aftermath of Genocide (University of Hawai’i Press, 2019) is the first major book exploring the relationship between the visual arts (film, painting, photography, installation) and Cambodian national identity in the present. In this groundbreaking book, Ly presents a number of creative artists whose complex and innovative work is fully worth much broader attention. But perhaps more valuably, to my mind, she gives us tools to understand them on their own terms.

The task of these contemporary artists is somber, burdened by the weight of the past and the anguish of not knowing whether their work is even worth completing. Early on, Ly reminds us of Theodor Adorno’s famous condemnation of poetry and his worry about living itself: “But it is not wrong to raise the less cultural question whether after Auschwitz you can go on living?” At the heart of this question is a deep moral skepticism. Can we trust in a world in which something so evil has taken place? Can the fulfillments of this world compensate for the guilt of survival and the suffering of loss? Can anyone aspire to create beauty in a place where such things have happened? Can one be reconciled with life after this? And yet these artists, in Cambodia and in the diaspora, continue to create and perform.

A survivor herself, Ly has had decades to ponder these questions in a specifically Cambodian context. A professor of the History of Art and Visual Cultures of Southeast Asia at UC Santa Cruz and a specialist in both the traditional and modern visual arts of Cambodia, Ly moves easily through complex iconographies that mix Hindu, Theravada Buddhist, and animist influences of texts ranging from antiquity to the present. Adding a finely-honed craft as a reader of art, familiarity with contemporary Cambodian artists, and a theoretically informed approach to trauma studies, she has made a truly original contribution to the study of the effects of collective and individual tragedy. Her writing is patient and straightforward, a pleasure to read. The book also contains a number of lovely color plates, making it practical for novices to this work.

Of course, Pol Pot and his brutal regime figure importantly, epitomized by the S-21 torture center, now an important museum in Phnom Penh. Ly devotes a chapter to images of Pol Pot sculpted and painted by prisoners of S-21, such as Vann Nath, whose survival depended on achieving ideologically-rigorous representations of Brother Number 1. Ly also gives expression to intermedial nuance, here exploring the added layers of meaning of the paintings and memories of the artists when refracted through the work of documentary filmmakers like Rithy Panh, whose influence is felt throughout the book.

But Ly’s patient approach allows her to broaden the historical narrative of what constitutes trauma in Cambodia, sending the reader back to the period before the Khmer Rouge, when American B52s were dropping millions of tons of explosives on Cambodia in its war against the Viet Cong, wreaking massive devastation that lured many young peasants into the ranks of a growing Khmer Rouge. An artist such as Vandy Rattana breaks the pervasive silence about the American bombings in a series of photographs called Bomb Ponds. Ostensibly, these images show typical rice fields and ponds, classically framed and vibrantly colored; but, in an accompanying video, two men relive their harrowing experiences of the bombings in ways that deconstruct the natural serenity. Ly’s detailed and subtle reading of this work combines both Western-inspired trauma studies and specifically Cambodian idioms, such as snarm or the “trace.”

It is in articulating these latter, specifically-Cambodian concepts, that Ly provides something precious in this book. Indeed, she has cultivated an original voice, cosmopolitan but entirely Cambodian, which contributes to the study of trauma and national identity. This places her in a small but growing movement of influential scholars and artists who are fluent in what has been called the Khmer “idiom of distress.” Take for instance, the idea of kamtech, a word used by the Khmer rouge to describe a crushing into dust, or an “elimination” (taken by Rithy Panh for the title of his autobiographical text). If the crime is a crushing, many Cambodians articulate its effects through the concept of baksbat, a concept developed in the clinical work of Chhim Sotheara. Narrowly, baksbat translates as “broken body” or “form,” but it extends also to “broken courage.” With concepts such as baksbat, kamtech, and snarm, Ly reads works of visual and performance arts in ways heretofore unavailable to many.

Her reading of Amy Lee Sanford’s Full Circle conveys the deep originality and strength that must have gone into this performance installation. Sanford gathers 40 clay pots (each representing a year of her life) around her in a circle. She picks up one pot; smashes it to the floor; and then picks it up and glues it back together, or, in some iterations, ties it together with a white string. Ly explains that the pots represent both broken bodies and female sexuality and change. The white strings evoke the Theravada Buddhist and animist ritual practice of gathering the “pralung,” or the nineteen “vital spirits,” which have escaped from someone who is distraught: in one version, the pralung are retrieved, gathered into clay pots, and then “tied” back into the person’s body using white string doused in holy water. Sanford’s work stops time for six days of destruction and repair, six days in which all of the pots are broken and tied up again: bodies broken and mended but still fragmented and covered with the fissures of baksbat.

Attuned to detail, Ly draws out the historical, spiritual, and political significance of the most banal objects. Her chapter on the krama – the gingham patterned cotton scarf worn throughout Cambodia – traces its multiple meanings from sources in traditional rural society through to its use in more recent rural land dispute protests and even the rainbow colored LGBTQIA+ krama. That the krama is often used during outdoor bathing or to dry the body makes it a logical choice for artists exploring eroticism and sexual identity in a country with rapidly changing attitudes toward queerness. Ly also explains how the late Vietnamese-Cambodian artist Lê Huy Hoàng gives creative expression to his problematic dual national identities through the krama. On a dirt floor, Hoàng executes a painstaking large-format (measured in meters) painting of the krama in yellowish (Cambodian) palm sugar, white (Vietnamese) cane sugar, and spent coffee grounds from his neighborhood café, only to see the painting eaten by ants over a period of days.

One of Ly’s strongest chapters spotlights the intricate connections between the Kingdom’s founding myths and its modern arts. The chapter is a marvelous translation of complexity into concision. It relates the stories of the serpent princess Neang Nak to the Apsara dance developed in the 1960s as well as to contemporary fashion and popular wedding ceremonies. This discussion becomes the backdrop for interpreting the choreographer, Sophiline Cheam Shapiro, who has reinvented court dance and reinterpreted the Serpent Princess as a diasporic female subject. In her choreography, Neang Neak hates the tail that entangles her as she turns on the stage, but after trying to cut it off, she realizes that “her tail makes her unique identity” and performs a “dance of acceptance” (118).

Many of the works Ly describes culminate in their own destruction. But some, like Shapiro’s dance and Sanford’s circle, also culminate in their poignant rebuilding. Many of Leang Seckon’s beautiful mixed-media paintings evoke a heavy burden of trauma, but some represent B52s dropping flowers instead of bombs (Leang believes some of the pilots must feel guilt), and generally Leang works in a style that Ly calls “marvelous realism,” defined as “a visual language suitable for the articulation of traumatic pain that would transform the experiences of atrocity into artistic expression, or at least help to ease pain and suffering” (51). None of the artists dealt with on these pages offers a definitive answer to Adorno’s doubt in the world. But Ly’s book about these courageous artists describes an art filled with possibility, one that would retain beauty without denying trauma, one that would encompass, as she writes, “both poison and remedy.” Ly’s work is a testament to this resistance to meaninglessness and despair.

Reviewed by Joseph Mai

Joseph Mai is Associate Professor of French and Film Studies, Clemson University