With the end of President Rodrigo Duterte’s term, the Philippines faces uncertainties on the kind of foreign policy the next leadership will pursue. Generally, there tends to be some adjustments in Philippine foreign policy and external behaviour whenever there is a new administration, as each president brings his/her own biases to the office. These adjustments will be based on how he/she perceives and promotes the nation’s interests, which are the basis of its foreign policy and conduct in international affairs. Yet in the pursuit of national interests, the incoming chief executive will have to face geopolitical challenges and deal with the controversial policies of Duterte, things which have significant implications in the future of Philippine foreign policy.

Philippine Presidency and Foreign Policy

The Philippine president is often referred to as the chief architect of foreign policy. With constitutional authority, he/she has wide political latitude to make decisive actions in upholding the nation’s interests in relation to other countries and international organisations. The president can reassess priorities, “dictate the tone and posture in the international community, and even personally manage diplomacy with selected countries if he/she so wishes, subject to some structural constraints” (Baviera 2015). Thus, the Philippine president is able to put his/her personal stamp on the nation’s foreign policy. In fact, an assessment of the Philippines’ international affairs and external relations is generally based on an evaluation of presidential administrations such as the Arroyo foreign policy (2001-2010) or the Aquino foreign policy (2010-2016).

Because of the personality—based political culture of the Philippines, its foreign policy tends to accentuate the personal idiosyncrasies of the president. This is especially evident whenever there is a leadership transition (every six years for each presidential term) as each leader brings his/her own biases to the office, resulting in the adjustment of the country’s foreign policy. Their individuality is even more apparent whenever they implement policy changes that are radically different from their predecessors. The more significant the difference in personality and outlook between two successive presidencies, the more radical are the changes in the Philippine foreign policy, and vice versa. For instance, Aquino’s cooperative personality and moralist global outlook promoted a liberal and institutionalist foreign policy. This is in stark contrast with Duterte’s forceful personality and socialist global outlook, which resulted in a realist and independent foreign policy for the Philippines.

National Interests in Foreign Policy

With the forthcoming leadership change, it is difficult however to predict the personality and the kind of foreign policy the incoming administration will pursue as it is unclear who will win in the May 2022 election. Yet an estimation of it typically necessitates an assessment of Duterte’s foreign policy to determine if there will be changes (or similarities) with his successor. This should serve as a contextual background and a starting point by which to compare their foreign policies.

It is also important to determine the multiple tasks and challenges ahead in the promotion of the nation’s interests that the next chief executive should take into account in his/her own foreign policy. These include the protection of the Philippines’ security interests by cultivating alliance with the United States amidst China’s maritime threats, the advancement of its economic interests with China and the United States, and the balancing of these bilateral relationships amidst their great power rivalry. Another crucial challenge for the incoming administration is dealing with the consequences of Duterte’s foreign policy pronouncements and actions that undermined the country’s democratic principles and human rights advocacy.

The Philippines’ Relations with China and United States

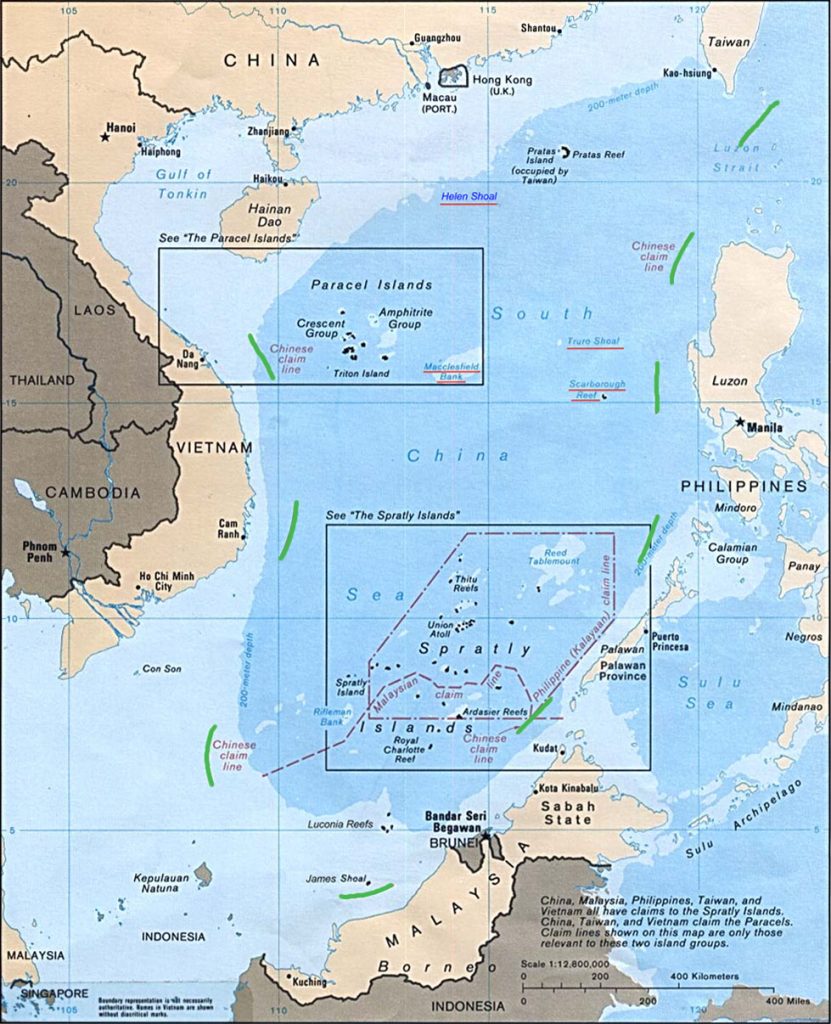

The Philippines’ territorial sovereignty and maritime rights are in peril with the persistent threats from Chinese maritime forces in the West Philippine Sea. In recent years, China’s maritime expansionist activities within its “nine-dash line” have become more aggressive and unhindered despite the Philippines’ 2016 arbitration award declaring them as illegal. However, the Duterte administration promoted an appeasement policy towards China by relegating its legal victory and downplaying China’s illegal maritime activities in exchange for US$24 billion in Chinese loans, credit and investments pledges to fund his “Build, Build, Build” programme. 1

Yet, much of that promised investment has not materialised, with projects delayed or shelved, while Chinese intrusion and illegal activities in the West Philippine Sea continued. Given these developments, the next administration’s foreign policy is expected to strategically protect the country against Chinese maritime threats while avoiding major compromises on the Philippines’ economic interests due to its reliance with China.

The Philippines’ military alliance with the United States has also experienced political turbulence during Duterte’s term. His much-touted “independent” foreign policy moved the Philippines away from its security reliance with the United States based on his long-held perceptions of American colonial subjugation. As a result, Duterte scaled down on joint military exercises and threated to terminate the Visiting Forces Agreement (VFA) in February 2020, which he eventually restored in July 2021. Thus, the upcoming leadership transition in the Philippines is an opportune time to renew its alliance with the United States. With China’s alarming maritime activities, the next administration can tap into US defence commitment under the 1951 Mutual Defence Treaty and determine the degree of American assistance it will allow. This can serve as a balancing force to mitigate the Philippines’ military vulnerabilities vis-à-vis China.

Aside from its security partnership, the Philippines can also deepen economic ties with the United States. In 2021, the United States is the Philippines’ second largest export market (after China) and the sixth source of import (after China and Japan). 2 Despite the long-standing political and economic ties, the Philippines has yet to sign an FTA deal with the United States. Duterte has since favoured Chinese trade and investments over the United States, which the next president should reconsider.

Moreover, the Philippines will have to cope with the increasing great power rivalry with the United States and China. This requires promoting an equidistant relationship with both and not favour one country over the other. According to former Filipino diplomat Leticia Ramos-Shahani, it is “the only way a seemingly poor country like ours can end its beggar-like dependence on big powers like the mighty USA or lessen its cowering fear of the arrogance of a superpower like China.” 3 The Philippines, under a new leadership, will have to skilfully advance its security and economic interests with both countries since these are equally important and are not mutually exclusive. The idea is to “acquire as many returns from different powers as possible while simultaneously seeking to offset longer-term risks.” 4

The Philippines’ Democracy and Human Rights

After Duterte’s term, the Philippines also has to deal with the consequences of his hostile pronouncements and actions against Western countries and international organisations. This was brought about by international condemnation regarding his brutal war on drugs that involved human rights abuses and extrajudicial killings. In response, Duterte denounced the United States, Canada, European Union, and other Western countries for intervening in the Philippines’ domestic affairs. He also slammed the United Nations by saying: “you have not done anything… except to criticise,” 5 and announced the withdrawal of the Philippines from the International Criminal Court (ICC) in 2018 after it started a preliminary inquiry on allegations of mass murder in his drug war.

These incidences do not bode well for a long-established democracy such as the Philippines, which diminishes its reputation particularly in ASEAN. Interestingly, the Philippines is one of the active members in the ASEAN Intergovernmental Commission on Human Rights and holds the highest number of international human rights treaties ratified among the 10 member states in the region. Such fact appears increasingly paradoxical given the incidences of human rights violations in the country. Moreover, the alarming tendency is that the drug war in the Philippines under Duterte may conveniently feed into the rationale of other governments in ASEAN to defy individual human rights (particularly those of drug suspects) to preserve the collective security of the majority.

The weakening of democratic values that guide Philippine foreign policy reflects the uncertainty and reservations on the permanence and universality of human rights in the country. This also reveals how human rights can sometimes be subjected to negotiations and compromises depending on who is in power. After Duterte, it is up to the next president to decide whether to continue undermining human rights or restore them as part of the country’s advocacy in its foreign policy.

The Next President

Whoever succeeds Duterte will have to consider these challenges in the pursuit of the Philippines’ interests in his/her foreign policy. How the next chief executive will promote the nation’s interests in relation with other countries will be based on the personality and global outlook by which he/she perceives them. Thus, some policy adjustments are expected from the incoming administration, which provides an interesting comparative assessment on the degree by which these changes are different (or similar) from the Duterte administration.

There is high anticipation of the kind of foreign policy the Philippines will promote under a new government. This is because of the serious consequences brought about by Duterte’s policy decisions and actions particularly on the Philippines’ relations with China and the United States, as well as its human rights record. These issues will be carried over for the next leadership to manage (or rectify) in crafting his/her foreign policy for the Philippines. How he/she will do so is an interesting and curious case for analytical observation.

Because of the president’s heavy influence, each leadership transition renders the country’s foreign policy in a state of flux. Yet, Philippine foreign policy across all presidencies shares a common feature—the lack of consistency in policy strategy that reveals a more reactive approach to international issues. To compensate for these, it behoves the 17th president of the Philippines to learn from the tactics and missteps of previous administrations that will enable him/her to craft a strategically-oriented foreign policy that will better advance the nation’s interest and skillfully capitalise on its external relations.

Andrea Chloe Wong

Andrea Chloe Wong is a Former Senior Foreign Affairs Research Specialist at the Foreign Service Institute of the Philippines and a Senior Lecturer at Miriam College in the Philippines.

Notes:

- Willard Cheng, “Duterte Heads Home from China with $24 Billion Deals,” ABS-CBN News,October 21, 2016, https://news.abs-cbn.com/business/10/21/16/duterte-heads-home-from-china-with-24-billion-deals. ↩

- “Highlights of the Philippine Export and Import Statistics July 2021,” Philippine Statistics Authority, September 9, 2021, https://psa.gov.ph/content/highlights-philippine-export-and-import-statistics-july-2021-preliminary. ↩

- Leticia Ramos Shahani, “Independent PH Foreign Policy,” Inquirer.net, August 2, 2015, https://opinion.inquirer.net/87250/independent-ph-foreign-policy. ↩

- Rafael Alunan III, “Understanding Independent Foreign Policy,” Business World, December 19, 2017, https://www.bworldonline.com/understanding-independent-foreign-policy/. ↩

- Duterte to UN Expert: ‘Let’s have a Debate,’ Rappler, August 21, 2016, https://www.rappler.com/nation/143711-duterte-un-expert-summary-executions-debate/. ↩