Myanmar (then known as Burma) had a brief democratic period from independence in 1948 until a 1962 coup, following which the military (known locally as the Tatmadaw) held near absolute power for almost five decades. An unanticipated political and economic opening began in 2010 and led to a decade of power-sharing between the military and successive civilian governments, first with the military-aligned Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP) from 2011 to 2015, and then the National League for Democracy (NLD). While the pace of democratic reform was at best modest, the decade of relative openness profoundly reshaped political norms and raised hopes for a better future among many, especially younger, citizens.

This ended abruptly on 1 February 2021: less than three months after the NLD’s November 2020 landslide election victory, the Tatmadaw launched a coup d’état and reinstated full military rule through the State Administration Council (SAC). In the weeks that followed, a broad pro-democracy movement took shape. It was met with violent repression from the Tatmadaw, which eventually led to a shift in the movement’s demands from a restoration of the pre-coup status quo to the total expulsion of the Tatmadaw from Myanmar’s political landscape.

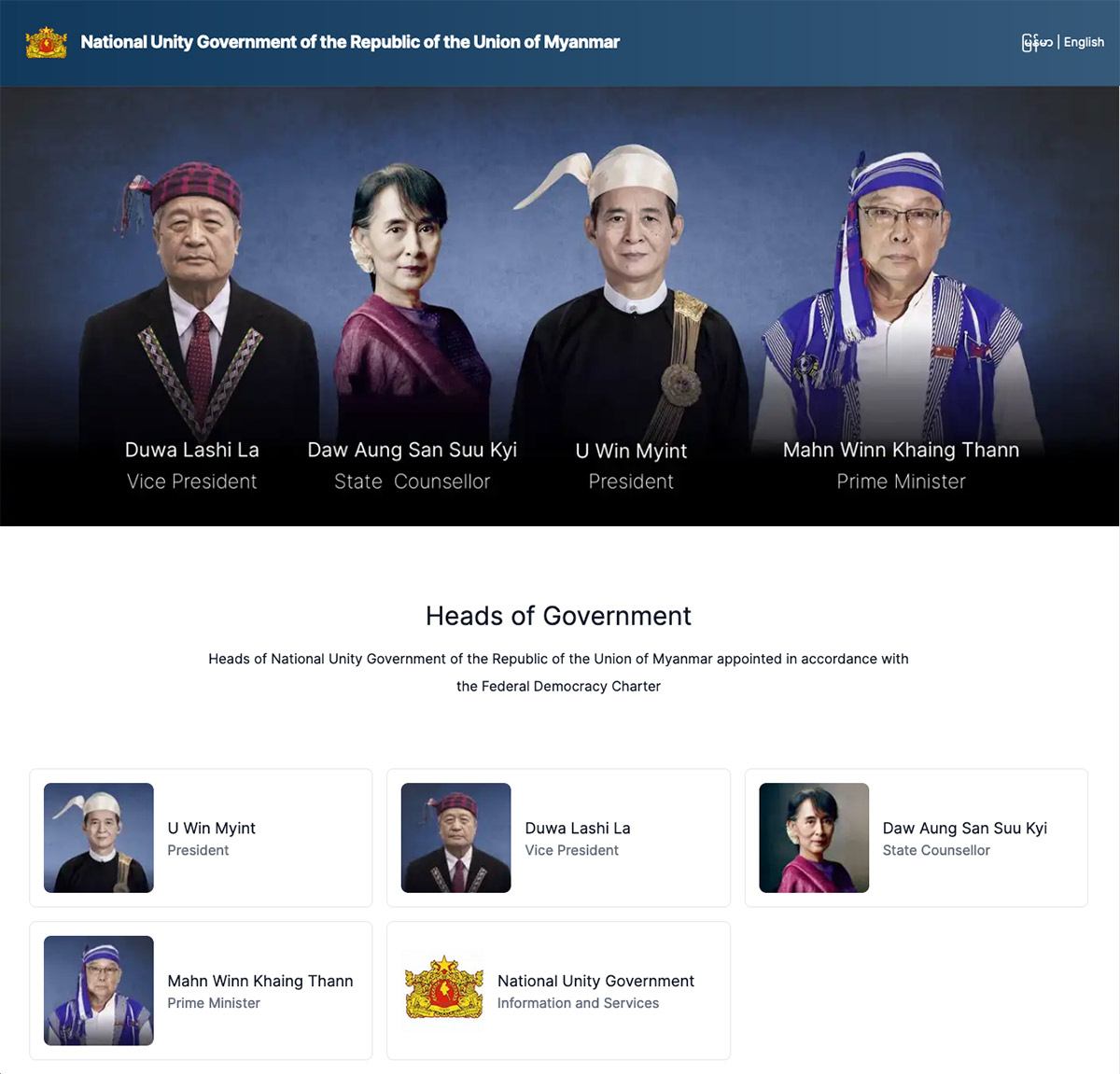

This article provides a brief analysis of Myanmar’s pro-democracy movement. We conceptualize the movement as comprising three main pillars: the mass protests; the Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM); and the Committee Representing the Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (CPRH) and National Unity Government (NUG). We also consider the special role of ethnic minorities. Much differentiates this movement from its predecessors, yet as in previous confrontations, the military’s vast advantages limit the movement’s abilities to achieve conclusive breakthroughs. This makes a protracted, costly, and ultimately tragic stalemate the most likely outcome.

Historical Background

Despite various forms of pro-democracy pressure, the Tatmadaw exercised almost complete control over the state for half a century prior to 2011. The regime’s durability results from several features. The Tatmadaw is the world’s only modern military to have been engaged without interruption in active conflict throughout its existence. Its central role in Myanmar’s foundation has led it to see itself as an embodiment of the country, and thus its adversaries as traitors. Extensive parallel institutions in areas ranging from education to healthcare limit interaction between military personnel and the civilian population. These features have allowed it to take extreme measures against perceived domestic threats, including pro-democracy movements and ethnic minorities.

Although a political transition was initiated in 2010, the Tatmadaw’s influence remained well protected: the 2008 Constitution guaranteed its autonomy, and granted it 25% of parliamentary seats as well as control over the key ministries of home affairs, defense, and borders. It established, in effect, an ad hoc power sharing arrangement with deliberately ambiguous terms.

Despite this, vast changes did occur both under the USDP and NLD governments. Internet access exploded, giving millions open access to the broader world and its ideas. A vibrant civil society emerged, which led public discussions on previously off-limits topics including democracy, social inclusion, and federalism. Large parts of the civil service became staffed by civilians with no ties to the Tatmadaw, reducing the military’s control over areas of the state. These developments fundamentally altered the dynamic between the Tatmadaw and the people, making the current pro-democracy movement distinct from its predecessors in important ways.

Mass Protests

The mass street protests are perhaps the most visible component of the pro-democracy movement. They have drawn in hundreds of thousands of people across cities, towns, and villages nationwide. They have also been overwhelmingly been spontaneous and leaderless, with their main protagonists coming from Generation Z youth, political and social activists, CSO and NGO leaders, and the artist community.

The first protests emerged in Yangon and Mandalay just days after the coup. Their visibility, coupled with the initial restraint showed by security forces, prompted ever larger protests in the following weeks. The ubiquity of smart phones facilitated coordination and enabled symbolically powerful linkages with international pro-democracy movements, including the Milk Tea Alliance Strike on 28 February that connected young Myanmar protesters with counterparts in Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Thailand.

The Tatmadaw’s initial restraint was short-lived: the first lethal crackdown occurred in late February. Subsequent crackdowns have involved increasingly brutal methods, including arbitrary arrests and shootings. At the time of writing in May 2021, over 800 protesters and bystanders have been killed, with many thousands more imprisoned and subjected to abuse. Internet shutdowns and media closures have severely restricted access to information.

In response to the violent crackdowns, protesters developed highly innovative alternative tactics. The early days of the coup had already seen the use of social media to call for boycotts of military-owned businesses and the products they supplied. These were highly successful: the once ubiquitous military-owned Myanmar Beer, for instance, become essentially unsellable and disappeared from shelves. Social punishment campaigns, also coordinated via social media, ostracized the families of prominent military officials. Offline, smaller, more mobile, and unannounced “flash protests” replaced the more lumbering early mass gatherings.

To protect themselves, frontline protesters began fashioning defensive weapons, as well as loosely organizing into “people’s militias” ranging in size from 20 to 500, some of which received financial support and tactical training from ethnic armed organizations (EAOs). While their objectives remained primarily defensive, opportunistic attacks using improvised explosive devices (IEDs) on police stations and government administrative offices began occurring in early May. In late May, the NUG announced the formation of a People’s Defense Force (PDF) as a precursor to a Federal Union Army. This marked an escalation in the conflict, as the PDF was instructed to join the EAOs in confronting the Tatmadaw across the country; indeed, while remaining decentralized, attacks against the Tatmadaw subsequently increased both in number and level of coordination, particularly in the ethnic minority states.

Residents in #Yangon #Myanmar protest against the #militarycoup by singing “Kabar Makyay Buu” on the street.#CivilDisobedienceMovement #RejectTheMilitary #WhatishappeninginMyanmar pic.twitter.com/5GkarA7mmI

— Civil Disobedience Movement Myanmar (@cdmovement_mm) February 3, 2021

Civil Disobedience Movement

The Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM) arose in conjunction with the mass protests; it has been led primarily by civil servants, including doctors, nurses, teachers, transportation workers, and bureaucrats from diverse sectors. The CDM began as spontaneous displays of defiance, primarily in the form of refusal to work. The gradual replacement of military linked personnel with civilians across the civil service since 2011 has allowed the CDM to reach a previously unimaginable scale.

At its peak, the CDM brough many sectors of Myanmar’s state and economy to a standstill: hospitals ceased to function, banks closed, goods remained stuck at port, and transportation networks came to a standstill. This directly and visibly contradicted the Tatmadaw’s claim that its seizure of power would stabilize the country and ensure a rapid return to “business as usual”. The symbolic impact of this paralysis has been immense. Beyond that, the CDM has also made it substantially more difficult for the Tatmadaw to govern, and has significantly disrupted some of the state’s most important revenue streams.

The CDM has been and remains fragmented. While this initially worked to its advantage by limiting the Tatmadaw’s response options, the CDM’s inability to effectively coordinate its actions has slowed momentum. As the confrontation draws on, an increasing number of civil servants have returned to work. This has less to do with a waning of conviction than with practical considerations: civil servants risk persecution from security forces and the loss of state-supplied housing; they also face loss of income at a moment when savings have already been depleted following the pandemic-related economic slowdown in 2020.

Committee Representing the Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (CRPH) and National Unity Government (NUG)

The CRPH was established on 5 February 2021 by a group of ousted parliamentarians (primarily from the NLD) to act as a parallel civilian government in opposition to the SAC. With the release of a new Federal Democracy Charter in April 2021, the CRPH announced the abolition of the 2008 Constitution that had structured politics during the power-sharing era.

While many protest groups see the CRPH as having legitimate authority over them, the CRPH has struggled to provide effective leadership. This is partly a consequence of its ad hoc formation, which leaves it without mechanisms through which to coordinate activities. Moreover, the CRPH has struggled to consolidate broad-based support, particularly among ethnic minorities. It has, for instance, been largely unable to secure the commitment of ethnic parties and EAOs to the Federal Charter, sections of which (particularly those relating to state parliaments and a federal army) remain contentious.

The formation of the NUG on 19 April was an attempt to broaden and further legitimize opposition to the SAC: while the NUG is built around the CRPH, it also includes protest leaders and representatives of ethnic minority groups, making it more ethnically diverse and less NLD-centric in composition than the previous government. Its prospects for success, however, depend largely on its ability to secure recognition: it faces significant challenges internationally, as well as serious hurdles in overcoming historic distrust not only of central authority among ethnic minority groups, but of the NLD itself.

Ethnic Minorities

There has been considerable variation in the response of ethnic parties towards the pro-democracy movement. Some, notably the Mon Unity Party and the Kayah State Democratic Party, have recognized and cooperated with the SAC. Others, including the Shan Nationalities League for Democracy have vehemently criticized the CRPH for its lack of ethnic representation, but still quietly supported aspects of the pro-democracy movement. Many other groups, however, most visibly under the banner of the General Strike Committee of Nationalities (GSC-N), have been impactful and innovative contributors to the pro-democracy movement, despite lingering tensions with the CRPH.

Similar variation exists in the orientation of Myanmar’s numerous EAOs. Some, for instance the Chin National Front and the Lahu Democratic Union, have openly joined the NUG in confronting the Tatmadaw. Other major actors like the Kachin Independence Army and the Karen National Union have reservations about the CRPH/NUG, but have nonetheless engaged with the pro-democracy movement and provided training to protestors, while continuing (or escalating) conflict with the Tatmadaw in their own name (rather than as part of the NUG). Another group, including the formidable United Wa State Army, have met with the SAC and remained largely silent about the pro-democracy movement, thereby suggesting an intention to avoid active participation.

Consolidating the support of these diverse actors will require adept maneuvering from the NUG. At the time of writing, it is unclear what to expect. The NUG has considerable support among the general public, particularly in ethnic majority areas, as the only visible alternative to the SAC. But despite clear efforts to be more inclusive of Myanmar’s diversity than past governments, some EAOs and CSOs lament that equality remains lacking, with the NLD-dominated CRPH still dictating developments.

Looking Forward

Through the various facets of the pro-democracy movement, Myanmar’s people have shown remarkable conviction in resisting the coup. The Tatmadaw, which grossly overestimated its own popular support, has been forced on the defensive. Despite this, it is almost certain that the pro-democracy movement cannot sustain its early strength. The brutal crackdowns and arrests have not only reduced mass protests, but also significantly impeded the movement’s ability to coordinate across its three pillars. The CRPH/NUG, excluded from formal institutions and confronted with long-standing center-periphery tensions, has unsurprisingly struggled to provide the decisive leadership needed to achieve a breakthrough in the confrontation with the Tatmadaw.

Yet the pro-democracy movement is far from dead. On the contrary, its members have shown that they are willing to accept immense costs to keep the hope of a democratic future alive. With every additional death or disappearance in their ranks, their animosity towards the Tatmadaw grows, making a return to the pre-coup power sharing arrangement unimaginable. The Tatmadaw faces its own daunting challenges: unable to break the spirit of the pro-democracy movement, but also seeing the prospects of a negotiated settlement that preserves its centrality in politics ever dwindling, it finds itself without tenable exit options, and must thus govern a country that is increasingly teetering towards state collapse. The tragic conclusion is that a violent and protracted stalemate, the human toll of which will be terrible, is the most likely outcome.

Kai Ostwald

Associate Professor, School of Public Policy and Global Affairs

University of British Columbia

Kyaw Yin Hlaing

Director, Center for Diversity and National Harmony (CDNH)

Myanmar