Prior to 2018, Malaysian politics were marked by regime and political stasis. Ruling coalitions headed by the United Malays National Organization (UMNO) party dominated politics in the country for an unbroken 61 years, making it one of the longest-running authoritarian governments in the world. This spell was broken in 2018, when a coalition of opposition parties, the Alliance of Hope (PH), won a decisive victory in national elections.

This brief article considers how opposition parties operated within Malaysia’s lower house, the Dewan Rakyat, during the long period of rule by the National Front. In the many decades of the BN’s hold on national power, the Dewan Rakyat was one of the few institutions available to the country’s opposition parties to advance their political agenda. Yet compared to studies of Malaysia’s elections and campaigns, attention to the workings of the parliament remain relatively rare.

I will discuss my ongoing research on legislative behaviour in this period of Malaysia’s political history. Despite barriers to strong accountability and oversight, it is clear that opposition MPs systematically used legislative institutions differently than their ruling government counterparts. Nevertheless, there is considerable variation in terms of the “role orientation” of legislators – that is, whether they focused primarily on parochial constituency matters, national policy influence, or government oversight. This research has relevance for understanding current behaviour in the Dewan Rakyat, as well as legislatures in other hybrid regimes in Southeast Asia.

Legislatures in authoritarian regimes

Influential scholarship on authoritarian regimes has tended to treat their formal institutions – like elections and legislatures – as serving the needs of autocratic leaders. Legislatures are often severely constrained, lacking the policymaking powers or accountability mechanisms present in their democratic counterparts. They are seen as a way to coopt potential opposition and legitimize authoritarian governments. 1 More recently, scholars have begun exploring actual legislative behaviour within such institutions, and the extent to which it resembles or differs from democratic systems. 2

Malaysia’s legislature during the National Front period was indeed a constrained institution. The role of legislators in the actual lawmaking process was limited; 80% of the bills introduced by the government are passed without any change. 3 Votes of no confidence were effectively impossible, and opposition motions or bills were almost never considered. In this period, the Dewan Rakyat met on average around 65 days in a year, much less than other Westminster systems. This situation is not much changed in the present day. Despite the change in government in 2018, only limited reforms were introduced.

How Malaysia’s opposition parties used constrained institutions

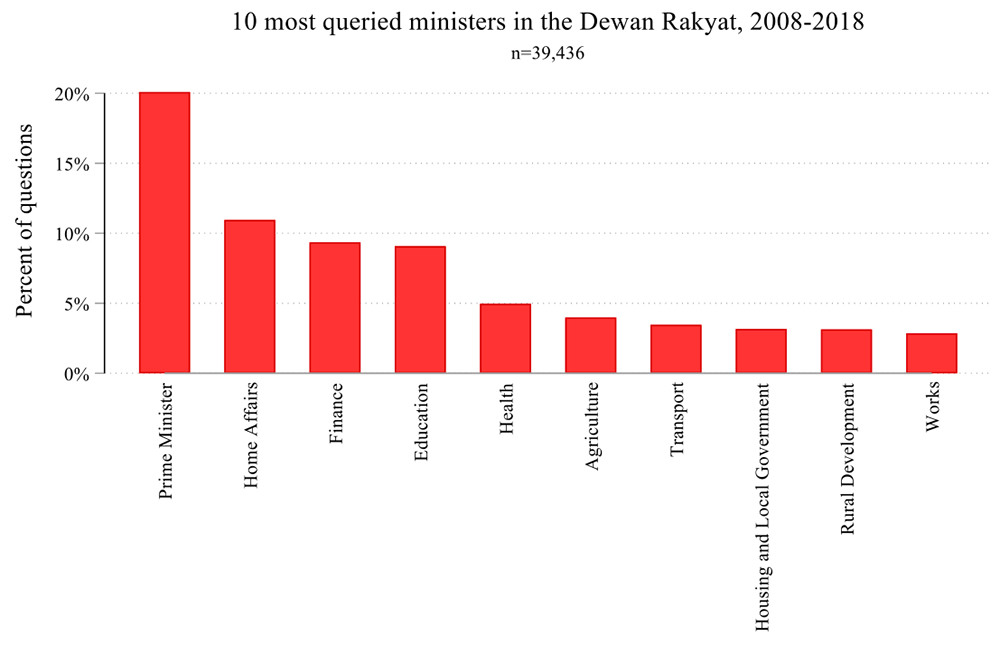

To understand patterns of legislative behavior, I compiled more than 39,000 oral questions submitted by Malaysian MPs. The focus of the research is from 2008-2018, a key period of political contestation during which the opposition made unprecedented electoral gains. During this period, the opposition sought to use these limited institutions and tools available – in particular, budget debates, motions and bills, and question time – to pursue oversight and accountability. 4The 2008 elections marked a decisive shift of opposition fortunes, in turn injecting greater significance to parliamentary questions, debates, and motions in the Dewan Rakyat. 5 This was observable in legislative behavior. The number of MPs submitting parliamentary questions increased noticeably after 2008. The tenor of the parliamentary debates also became more contentious: as the then-Speaker of the House, Pandikar Amin, remarked, “My God! Almost every day, there was a fight, especially in 2008 and 2009.” 6

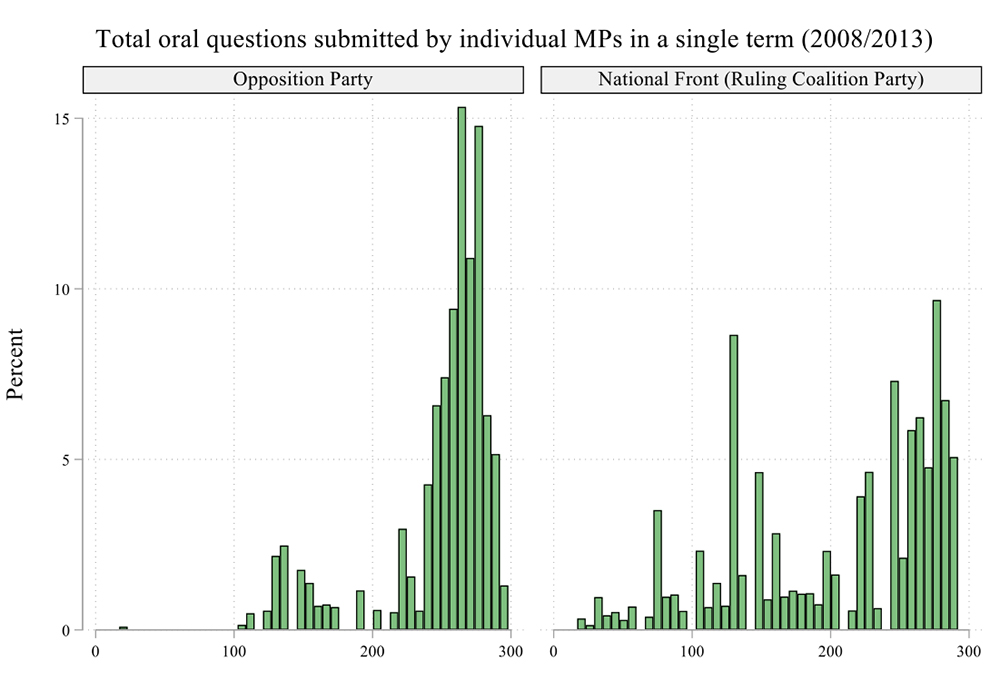

Opposition MPs in this period were particularly active in using parliamentary questions. Despite holding an average of 39% of the seats across the two terms, the main opposition parties at the time – PAS, DAP, and PKR – submitted 57% of questions. The figure below shows that individual opposition MPs were also more likely to submit a high number of oral questions, even while excluding ruling party MPs who held ministerial positions at the time. This is in line with findings from democratic settings where opposition parties are more active in question time. 7

MPs were cognizant of the ability of parliamentary questions to raise public awareness. As a political party staff member working on the legislature described in an interview, asking parliamentary questions is “a political act… if you ask the right question, [then it will] get published in the media.” 8 This was particularly true for questions which were asked live on television: 2008 marked the first year that a 30-minute live telecast of question time was introduced, reaching a large audience of Malaysians. Due to time constraints, only the first 10-15 questions are answered by ministers on the open floor of the Dewan Rakyat, allowing for not only television coverage but also a chance to ask a follow-up question.

The questions provide an important record on the political priorities and role orientations of sitting MPs. The questions cover an extremely wide variety of topics, ranging from diplomatic relations, government projects and programs, to individual constituent matters.

While analysis is ongoing, the most common question type appeared to focus on inducing government responsiveness. More than one-third of questions query about the status of particular government programs, decisions, and initiatives at all levels of government. Requests for basic information and statistics from government agencies were also common.

Preliminary interviews with MPs suggest that the opacity of government decision making and lack of transparency meant that questions could sometimes yield useful information. These questions also served a function as implicitly highlighting government underperformance, and as one opposition MP noted, force ministries to explain why particular projects had been stalled or abandoned. 9 Another MP noted that the ministries “loved those kinds of questions” given the relative ease by which they could be answered, rather than more difficult or controversial issues. 10

These types of questions also can be construed as showing a role orientation focused on cultivating a local reputation. Malaysia’s MPs are notorious for their focus on cultivating relationships with their constituents through service centers and intermediation on behalf of individuals. 11 But under the National Front government, opposition politicians were denied access to constituency development funds that ruling government MPs could result in. As a result, parliamentary questions could not only induce limited responsiveness, but also allow MPs to claim credit for looking out for constituents.

Opposition MPs were twice as likely to ask a question with a critical tone, coded as questions that asked for explanation or justification of government policy. They were more likely to ask about controversial issues that highlighted misdeeds by government officials: 82% of questions related to corruption were asked by the opposition. Similarly, 81% of questions on electoral conduct, voter rolls, redistricting, and district boundaries – key to maintaining the National Front’s hold on power – were asked by the opposition. After the massive 1MDB corruption scandal came to light in 2015, MPs (largely from the opposition) submitted over 300 questions. Yet the government appeared to place them with a low question number; only 4 had a question number high enough to be directly answered on the floor. The then-Speaker of Parliament Pandikar Amin also rejected more than 30 additional questions related to the 1MDB scandal. 12

There were strong regional differences in MP role orientation. 36% of the questions asked by MPs from East Malaysia mentioned either their constituency or one of the two East Malaysian states. Regional parties in East Malaysia were most likely to ask parliamentary questions regarding their constituency, often focused on particular roads, schools, or projects in their constituency. Comparative evidence suggests that such constituency-focused requests are common. A study of questions of Ireland’s parliament found that staffing issues, resources, and facilities at specific schools and hospitals in the MP’s constituency were also common. 13

Implications

What does this mean for our understanding of legislatures in authoritarian regimes? While legislatures in hybrid regimes like Malaysia are comparatively underpowered, legislative behavior still offers an important avenue to understanding how MPs view their role within constrained institutions. The preliminary evidence described here suggests that opposition MPs developed a distinct mix of constituency service, government oversight, and grandstanding. Additionally, the specific institutional details of institutions – such as how parliamentary questions are submitted, ordered, and answered – become highly consequential to how effective or ineffective such institutions are.

Despite the unprecedented change of government in 2018, Malaysia’s parliament remains largely unreformed. The victorious Alliance of Hope coalition had made extensive promises for parliamentary reform, but largely failed to realize them. 14 Nevertheless, recent political instability has seen the Dewan Rakyat emerge as an important battleground as competing interests have sought to prove their competency. While the reform process remains stalled, the Dewan Rakyat is likely to play a more decisive role for testing the stability of governing coalitions and extracting genuine concessions from the government of the day.

Sebastian Dettman

Sebastian Dettman is an assistant professor of political science in the School of Social Sciences at Singapore Management University.

Banner: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia-March 11,2019. Malaysian member of Parliament take at their seat in parliament house during parliament session in Kuala Lumpur. Photo: S.O / Shutterstock.com

Notes:

- Jennifer Gandhi and Ellen Lust-Okar, “Elections Under Authoritarianism,” Annual Review of Political Science 12, no. 1 (June 2009): 403–22. ↩

- Jennifer Gandhi, Ben Noble, and Milan Svolik, “Legislatures and Legislative Politics Without Democracy,” Comparative Political Studies 53, no. 9 (August 2020): 1359–79, https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414020919930. ↩

- Mohamad Ariff Md Yusof, Roosme Hamzah, and Shad Saleem Faruqui, Law, Principles and Practice in the Dewan Rakyat (House of Representatives) of Malaysia (Thomson Reuters Asia Sdn Bhd, 2020), p 36. ↩

- See e.g. Muhamad Fuzi Omar, “Parliamentary Behaviour of the Members of Opposition Political Parties in Malaysia” 16, no. 1 (2008): 28; William Case, Executive Accountability in Southeast Asia: The Role of Legislatures in New Democracies and Under Electoral Authoritarianism (Honolulu, Hawaii: East-West Center, 2011). ↩

- Yusof, Hamzah, and Faruqui, Law, Principles and Practice in the Dewan Rakyat (House of Representatives) of Malaysia. ↩

- http://www.dailyexpress.com.my/read/1163/there-was-a-fight-almost-everyday-pandikar/ ↩

- Frank R. Baumgartner, Christian Breunig, and Emiliano Grossman, Comparative Policy Agendas: Theory, Tools, Data (Oxford University Press, 2019). ↩

- Political party staff member interview, October 22, 2020. ↩

- MP interview, October 23, 2020. ↩

- MP interview, October 22, 2020. ↩

- Meredith L. Weiss, The Roots of Resilience: Party Machines and Grassroots Politics in Southeast Asia (Ithaca New York: Cornell University Press, 2020). ↩

- https://www.malaysiakini.com/news/390104 ↩

- Shane Martin, “Using Parliamentary Questions to Measure Constituency Focus: An Application to the Irish Case,” Political Studies 59, no. 2 (June 2011): 472–88, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2011.00885.x. ↩

- Khoo Ying Hooi, “Post-Legislative Scrutiny (PLS) in the Process of Democratic Transition in Malaysia,” Journal of Southeast Asian Human Rights 4, no. 1 (June 17, 2020): 52, https://doi.org/10.19184/jseahr.v4i1.13591. ↩