Myanmar’s abounding despair gave way to euphoria when the National League for Democracy (NLD) led by Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, won a landslide victory in the 2015 general elections. Another landslide in 2020 suggested the possibility of consolidating democracy, but the military had other ideas and launched a coup on February 1st to thwart the will of the people just as it did thirty years ago. But unlike then, the people have had a taste of democracy and the genie is out of the bottle. The military can gun down protestors but is powerless to kill the ideals that motivate the pro-democracy movement. At best the junta can win a Pyrrhic victory in relying on its ghastly tactics of repression, but this is a recipe for prolonged instability and a national catastrophe. Unleashing paramilitary goon squads to roam the streets beating and killing unarmed peaceful protestors is a sign of the junta’s monstrous desperation and moral bankruptcy.

In Mandalay’s early March protests Kyal Sin, a 19-year-old woman also known as Angel, was killed by a shot in the head. She was wearing a t-shirt proclaiming, ‘Everything Will be Ok’. This haunting image is etched in the global memory where nightmares linger, a stark reminder that democracy, and the hope it offers, is being savagely crushed. She has become an iconic symbol of Gen Z’s gutsy defiance of the military crackdown.

Millions of other citizens across Myanmar reject the military coup and seek to oust the illegitimate junta that has derailed the nation’s fledgling democracy. They also seek justice for those killed in the protests and the release of their revered leader Aung San Suu Kyi, now held on trumped up charges, and thousands of other pro-democracy detainees.

The long arc of the military’s malevolence has traumatized Myanmar’s people. For them, nothing can be ok if the junta prevails. Recalling the bad old days, Lily Kyawt, a pseudonym for a Burmese resident of Japan, reflected “We are re-experiencing the collective trauma of living under the grip of the military. Everyday violence against protesters escalates and reminds us, those who have lived and grown up under the military regime and who witnessed many violent crackdowns since 1962, of the dark times.” She adds, “The pain, sadness, anger, and anxiety of the families of those young people killed and arrested are unfathomable” and asks, “How do you fight an institution that does not hesitate or that has no remorse using any weapon available to kill their own people who just are asking for the rights they deserve?” The traumas of preceding generations thus cast a long shadow over the current uprising and “earnest hopes of the new generation to sustain the resistance to the coup against all odds.” The military justifies its putsch by asserting it is defending the rule of law, but that argument doesn’t bear scrutiny.

Unconstitutional

General Min Aung Hlaing seized power on the flimsy pretext of voting irregularities, invoking the 2008 Constitution that grants the head of Tatmadaw (the military forces) emergency power to intervene, but only under extraordinary circumstances to protect the nation and its people. In Jurist, Melissa Crouch, a law professor at the University of New South Wales and expert on Myanmar’s 2008 Constitution, argues that the military used, “unconstitutional means to declare a constitutional emergency.”

She concludes that, “In effect, the Commander in Chief has jumped to section 419 of the Constitution, the provision that gives him the right to exercise all powers in an emergency, without going through the right processes to get there.” Adding that, “the Constitution envisions a state of emergency as temporary and provides that the elected members of parliament can resume office once a state of emergency ends.” That does not seem to be the current plan as junta kingpin Min Aung Hlaing has announced that new elections will be held next year, presumably after convicting Aung San Suu Kyi on trumped up charges and dissolving the National League for Democracy (NLD), removing the party that won 70% of the votes from participating in sham elections. This egregious trampling on the constitution, however, pales in comparison to the ongoing extrajudicial executions of unarmed civilians by security forces, mass incarcerations and torture of prisoners.

The murder of scores of unarmed demonstrators by security forces running amok renders the junta’s justification absurd. Matthew Bugher, the Bangkok-based Southeast Asia director of Article 19, a global organization that advocates in support of freedom of expression, says, “The military’s assertions that the coup was necessary to uphold the rule of law or the constitution are absolutely farcical. The coup itself was unlawful, even if judged against the warped, pro-military legal regime established by the constitution. The lawlessness witnessed since the coup—soldiers firing into homes, medical workers being attacked, show trials for democratically elected officials—is the antithesis of the rule of law.” He adds, “Ultimately, if the military’s plans are defeated, it will be because of the bravery and determination of the Myanmar people. However, a strong international response is needed to support the domestic pro-democracy movement. Most urgently, the UN Security Council should impose a global arms embargo on Myanmar.” In his view, the bloody mayhem unleashed by the junta constitute crimes against humanity and, “The Security Council should refer the situation in Myanmar to the International Criminal Court without delay. Governments should also ensure that other investigative mechanisms are properly resourced and supported.”

Resetting Democracy

It seems the military was incensed by moves that The Lady, as Aung San Suu Kyi is known domestically, initiated in March 2020 to amend the constitution to curtail the military’s political influence by removing its power to veto any proposed constitutional amendments. As Myanmar expert Bertil Linter argues, “The main reason for the coup appears to be that the top brass had grown tired of civilian politicians who have repeatedly tried to amend the constitution to reduce the power of the military, now represented by its control of a quarter of all MPs and the three most important ministries: defense, home affairs and border affairs.”

Under the 2008 Constitution, the military reserved 25% of all seats in parliament for serving officers and stipulated that amendments required more than 75% support in the legislature and majority support in a national referendum. The NLD amendment proposed lowering the bar to eliminate the military veto by requiring that constitutional revisions gain two-thirds support of elected representatives. It also proposed a phased in reduction of the military’s percentage of reserved parliamentary seats, to 15 percent after the 2020 election, 10 percent after 2025 and 5 percent after 2030. Both amendments were defeated, but the military became anxious and angry about the NLD’s efforts. It also appears that the military’s strategy to peel away ethnic political support was getting nowhere while the NLD was reportedly negotiating association arrangements with minority parties that would strengthen its hand.

According to Tina Burrett, a political scientist at Sophia University, “the military are trying to present themselves as a more effective force in dealing with the needs of ethnic minority groups than the NLD government [and] they were criticising the healthcare workers who’ve joined the civil disobedience movement for abandoning hospitals in ethnic minority areas and are promising better access to healthcare (this in the context of the pandemic).” She believes the military is also claiming it is better able to negotiate ceasefire agreements than the NLD, but “I don’t think any of this is going to convince ethnic minority citizens. The election results suggest ethnic minority voters were wise to the military’s divide and rule tactics. And the protests in minority areas seem as well attended as in the rest of the country.”

The post-Suharto transition from military rule in Indonesia (1967-1998) provided a model for Tatmadaw, including the reservation of 25% of parliamentary seats. There were some in the Indonesian military that favored a hardline and retaining power, but reformists carried the day, arguing that institutional interests were better served by returning to barracks. Subsequently, the military voluntarily relinquished all of its reserved seats. In Myanmar, the military retained de facto power, meaning a tethered democratization conceding limited powers to Aung San Suu Kyi’s government. Instead, the Indonesian military relied on an implicit understanding that there would be no efforts to pursue accountability over past crimes and abuses, and that its economic interests were off limits. Of course, having the guns helped to remind everyone what was at stake, but this informal guarantee paved the way for a successful democratic transition that appears increasingly unlikely in Myanmar. Tatmadaw has a lot to answer for—a half century of incompetent governance, institutionalized malfeasance and violent repression of pro-democracy uprisings in 1988, 2007 and now 2021, along with decades of ethnic repression—and it is widely despised.

In the 2020 general elections the military suffered a comprehensive humiliation as its proxy party, the Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP), was decimated while Aung San Suu Kyi’s NLD won 396 seats versus 33 for the USDP. Nonetheless the USDP and military, taking a page out of the Trump playbook, declared fraud without presenting any substantiating evidence despite international election monitors, including the EU, the Carter Center, and the Asian Network for Free Elections, all validating the elections as free and fair. Certainly, there may have been some irregularities, but the repudiation of the military was comprehensive. If anyone had any doubts, sustained mass protests by pro-democracy activists across the nation, braving bullets and beatings, manifest the thwarted will of the people. The carnage on the streets is grim proof of what they are prepared to sacrifice for democracy.

The military was always ambivalent about democratization of any sort and did so grudgingly to ease sanctions. Turning on the spigots of aid and investments required democratic reforms and cohabitation with Aung San Suu Kyi and an NLD government. But for Commander in Chief Min Aung Hlaing, her usefulness and that of democracy had run its course following sanctions imposed due to the military’s expulsion of >700,000 Rohingya in 2017 and the scaling down of western aid and investments. Ironically, the desire to reach out to the West was driven in part by concerns about growing Chinese influence, but now Beijing is even more influential due to the military’s anti-Rohingya campaign. There may be some satisfaction among the junta leaders that The Lady suddenly also became an international pariah for resolutely defending the expulsions, but that also meant she was no longer useful for attracting western aid and investments. She and democracy were deemed expendable. To be clear, this outcome was precipitated by the military’s shredding of human rights, not the sanctions they provoked.

Sanctions vs Engagement

The sanctions versus constructive engagement debate has resumed with advocates of smart sanctions and targeted sanctions maintaining that engagement has been cover for doing business with odious regimes under the pretext of reforming them. In the absence of pressure there can be no meaningful engagement beyond abject capitulation. Engaging the junta with sanctions is about helping the people in Myanmar overcome the putsch and restoring democracy. The problem for the soft engagement camp is the lack of success in Myanmar/Burma over several decades.

True, the top brass can live with international isolation, travel bans, targeted sanctions and condemnation, but fears the will of the people because it has treated them so appallingly. Since mounting the coup, its bad karma keeps piling up. According to journalist Saw Yan Naing, this means the military believes it must prevail at all costs on terms it dictates.

And this is precisely why pundits calling for a soft approach to the coup in the hopes of a mediated settlement are deluded. The junta will only accept an outcome favorable to the military, so in effect the anti-sanctions, anti-condemnation punditry is only playing into the hands of the military by encouraging a process that inevitably will lead to business as usual, damn the scruples and will of the people. These experts position themselves as the adults in the room, imagining that they can manage the situation but surely exaggerate their influence. As veteran Burma-hand Bertil Linter explains, “those advocating ‘engagement’ and ‘dialog’ with the new junta are overestimating their own importance.”

Tom Andrews, the UN Rapporteur for Human Rights in Myanmar, has called on the UNSC to impose tough sanctions and to hold the top brass accountable by referring the case to the ICC for investigation and prosecution of those deemed responsible for inflicting violence on the people. He has also called on nations not to wait on the UNSC, and to coordinate tough targeted sanctions against the junta, arguing that economic pressure works and is the main reason why Tatmadaw endorsed a democratic transition a decade ago. In his view, the top generals were eager to end isolation because they saw good opportunities to enrich themselves, and thus sanctions nudged them towards democratization.

On March 11, the UN Security Council condemned “the violence against peaceful protestors, including against women, youth and children. It expresses deep concern at restrictions on medical personnel, civil society, labour union members, journalists and media workers, and calls for the immediate release of all those detained arbitrarily.” The UNSC also warned the military to exercise restraint. Richard Gowan, from the International Crisis Group, acknowledges that the UNSC statement, “is weaker than most Western members would like. And it is stronger than China and Russia would prefer. So it is mildly unsatisfactory for everyone, but it sends the generals in Myanmar a message that the UN is still watching them, and Beijing won’t give them total cover for human rights abuses.” China’s UN Ambassador Zhang Jun asserted, “Now it’s time for de-escalation. It’s time for diplomacy. It’s time for dialogue.” In this context, UN backing for sanctions seems unlikely.

Many observers disagree with sanctions of any kind, arguing they are counterproductive. In an email, Soe Myint Aung, founder of the Yangon Centre for Independent Research, maintains that the “sanctions were too early. This has locked 15 or so generals at the top with no exit. They won’t flee to any country but rather fight back and die here.” He sees no signs of any divisions within the military as all of Tatmadaw is implicated in the brutal crackdown, “leaving no space for mutiny.”

Lintner dismisses this ‘blame the sanctions’ view, arguing that “I have heard that argument too, but from foreigners only. It would be hard to find any Burmese who would agree. And it was brutal repression they unleashed that’s the cause for those measures, not that the measures forced them to become brutal.” The generals anticipated the wrath of the international community and they have shrugged off sanctions before so being sanctioned and isolated is not a cause for its uncompromising hardline because compromise is not part of the military’s institutional DNA.

To be clear, it’s the military that has thrown the nation into chaos and provoked global condemnation. Some pundits argue against antagonizing Tatmadaw, that this might cause an escalation of repression and thwart attempts to solve the problem through mediation. Can it get much worse than mass arrests, vicious beatings and mowing down unarmed demonstrators? Yes, it can as the military intensifies its efforts to defy the will of the people and cow them into submission. There is no turning back. The military has crossed the Rubicon and they are inured to global censure; only the credulous imagine it contemplates significant concessions in any mediation. Condemning their awful abuses of power is not shutting a door that is already bolted shut. Surely, pro-democracy activists want more from the world, but equally they want and deserve no less than global support for respecting the outcome of the 2020 elections. Repudiation and sanctions offer symbolic support to a beleaguered people and punctures the junta’s cocoon of impunity.

Sweeping trade bans are not the answer because they harm the already desperately poor and vulnerable. Targeted sanctions are not a panacea but are effective in penalizing perpetrators. It’s a mistake to imagine targeted sanctions are a plan to bring the junta to its knees but being frozen out of the international financial system makes life more difficult for the targets. Sanctions won’t oust the generals but will let the demonstrators know they are not alone. Generation Z supports sanctions as does Myanmar’s envoy to the UN.

From street protests, the Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM) and blogs, it’s hard to miss the message from Myanmar: they would rather suffer than be enslaved by the military again. The Federation of Garment Workers has staged strikes and called on international brands to denounce the coup and curtail business ties while the Confederation of Trade Unions also supports sanctions. Union spokesmen understand the incredible economic suffering this will cause but argue this is preferable to returning to military rule. As the economy implodes due to a strike of transport workers and customs workers, trade has dropped by some 90%.

This the result of the CDM and self-imposed sanctions by the citizens of Myanmar to undermine the junta. They seek the international community’s support not just the empty platitudes of engagement. Do wishful mediators imagine the protestors will just get over it and accept the junta’s fait accompli and compromise with it? As one blogger posted, “People are willing to sacrifice everything as long as military dictatorship doesn’t survive. Military junta will survive if everything is functioning as usual. That’s how much everyone hates them. Living with constant fear under dictatorship is the same as ‘not living’ at all.” Another explained,” We are doing this to shut down the system of the whole country so the regime could not run it. Call it mutual suicide.” And, “Death is unpleasant but better than living under slavery and dying everyday”.

President Biden is unlikely to engage with the junta because he has made human rights and democracy central to his foreign policy agenda. In 2020, the US gave US$135 million to Myanmar, but this won’t be cut by sanctions because almost all of it went to nongovernmental and civil society organizations, and it seems such assistance will be maintained. The US government moved quickly to block the junta from seizing US$1 billion from Myanmar’s account held with the Federal Reserve Bank of New York just days after the coup. President Biden subsequently issued an executive order that gave the Fed the legal authority to freeze these foreign currency reserves indefinitely. But an additional US$5.7 billion of Myanmar’s foreign exchange reserves are held by three Singaporean banks– DBS [Development Bank of Singapore], UOB [United Overseas Bank], and OCBC [Overseas Chinese Banking Corporation].

On February 23, the Monetary Authority of Singapore declared that its “regular surveillance of the banking system has not found significant funds from Myanmar companies and individuals in banks in Singapore.” According to Radio Free Asia, this is an evasive statement because it overlooks the government funds that the junta wants to use to cushion any blow from sanctions.

The Singapore case highlights that the key problem of sanctions is lax enforcement. It was supposed to be hard for Myanmar to acquire dual use technologies that state security could deploy to mount surveillance and suppress dissent, but that apparently has not been a problem at all. State security has a formidable digital arsenal of hacking software, spyware and surveillance drones even though sales are supposedly banned.

The New York Times details the shadowy web of businesses that have helped the security services evade sanctions and upgrade their cybersecurity capabilities to target coup opponents. It reported documents showing, “tens of millions of dollars earmarked for technology that can mine phones and computers, as well as track people’s live locations and listen in to their conversations.” Some came from Russia and China, but even after sanctions were imposed for the military’s expulsion of Rohingya in 2017, Tatmadaw was able to purchase tracking hardware and forensic software from American, European and Israeli firms that enhanced the state’s surveillance infrastructure.

Linter believes that, “The strategy of the coupmakers seems to be to shoot the population into submission and once that has been done, the outside world would have no choice but to accept fait accompli. But that’s not going to work either. Sanctions and boycotts may not have that much of an impact but they will prevent normalization of the coup.”

The US has ratcheted up sanctions targeting the junta chief’s adult children, and more are pending. The US sanctions mean that “all property and interests in property controlled by those sanctioned, either directly or indirectly, individually or with other blocked persons, which are in the US or in the possession or control of U.S. persons, are blocked and must be reported” to the Department of Treasury. The covert activist group Justice for Myanmar promotes accountability and has called for international sanctions targeting 18 firms linked to the junta, their families and cronies.

Concerted sanctions are unlikely, however, because the UN Security Council and ASEAN are paralyzed, and China is unlikely to pressure the regime because in principle it opposes political intervention and also seeks to preserves its access and interests.

China Win?

Linter believes that, “As the dust settles on Myanmar’s military coup, it is already clear that China will be the main foreign power beneficiary of the suspension of democracy.”

In an email he explained that “The main reason why Japan doesn’t come out more strongly is that Tokyo is wary of the consequences harsh criticism would have on its relations with the new military-installed coup government: it would push it more firmly into the hands of the Chinese. It was for the same reason Japan, unlike the West, declined to condemn the violent expulsion of several hundred thousand Rohingya Muslims into Bangladesh in 2017.”

“But, on the other hand” Linter adds, “Japan is one of very few countries that the military might listen to. The Japanese ambassador in Yangon is a fluent Burmese speaker and has over the years had many interactions with the Myanmar establishment, military as well as civilian. And the Myanmar military would welcome an alternative to being pushed back into China’s embrace (it was that dependence which led to the country opening up to the West and the rest of the world in 2011/2012). The fiercely nationalistic Myanmar military is actually deeply suspicious of the Chinese and their intentions which they see as a threat to national sovereignty. “

According to Lintner, Chinese business groups and policymakers are concerned about the status of deals they struck with the NLD government and Beijing does not see this as an unalloyed win because it got along reasonably well with ASSK and has had more difficulty in dealing with the ultra-nationalistic military. The Rohingya crisis, and western sanctions, created an opportunity for Beijing, and Myanmar reciprocated by endorsing China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and reaching an agreement in 2018 on the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC). Beijing is keen to maintain these gains so is unlikely to act against the junta and risk its CMEC access to the Indian Ocean. Coup leader General Min Aung Hlaing is known to be wary of China’s regional hegemonic ambitions and influence in Myanmar. He played a role in diversifying weapons procurement to lessen dependence on China by cutting deals with Russia. He and other military leaders are also unhappy about Chinese support for ethnic insurgencies, including arms sales. However, Russia and China have been reliable partners, keeping the UNSC at bay by blocking any proposals to take action against the military over the Rohingya or recent coup. Newly appointed junta foreign minister Wunna Maung Lwin is known for his pro-China anti-Western views, signaling the regime’s hopes for continued Chinese support.

Anti-Chinese protests also refute the China win scenario. As Lintner adds, “the coup, and public perceptions of China’s support for it, has given rise to very strong anti-Chinese sentiments: daily demonstrations outside the Chinese embassy in Yangon and calls for boycotts of Chinese goods. The anti-China backlash has been so strong that the Sino-Myanmar community had to come out with a strong statement saying that they support the civil disobedience movement, not what China has done and is doing.”

Tokyo warns that there is a risk of driving Myanmar into China’s embrace, which is exactly the same argument that the junta’s recently hired PR lobbyist, a former Israeli intelligence official, has been making.

Invoking the possibility of a major geo-political win for Beijing has provided useful cover for Japan’s reluctance to impose any sanctions at all, opening a gap between Tokyo and Western counterparts. The ten-member Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) has also shied away from taking any action against the junta, based on the principle of non-intervention and longstanding commitment to paralysis in the face of crisis. Moreover, ASEAN is divided over the coup due to serious democratic backsliding in the regional group, notably Cambodia, the Philippines and Thailand, while Vietnam remains authoritarian. Jun Honna, a Southeast Asian expert at Ritsumeikan University in Kyoto, doubts that ASEAN or Japan will exert any significant pressure on Myanmar’s military regime to restore democracy and is equally skeptical about the possibility of any intervention based on invoking the Responsibility to Protect (R2P).

The Japanese government is concerned, however, about the widening rift with Washington over how to respond to the coup because the Biden Administration has a foreign policy that emphasizes human rights and democracy and has been unhappy with Tokyo’s minimalist handwringing. On March 8 Ambassador Maruyama met with the junta’s foreign minister but the two sides disagreed on what was discussed. The junta maintained that the talks focused on enhancement of friendly bilateral relations while the embassy asserted that it called for an end to the killing, the release of all detainees and restoration of democracy.

Japan remains under US pressure to impose targeted sanctions against the military and companies it controls, support a global arms embargo and suspend all development projects. Such policies are well outside Tokyo’s comfort zone and it remains convinced that these are counterproductive measures unlikely to modify the junta’s behavior. Yet, Japan has little to show for its tactics of persuasion since the last time the military overruled the general election outcome three decades ago.

Corporate Social Responsibility?

International firms operating in Myanmar are in a quandary.

They don’t want to burn bridges with the junta, probably anticipating that it will outlast the pro-democracy movement, but they also don’t want to be seen as indifferent to the suffering of the people or abetting the regime. Local boycotts of products would have limited impact on the bottom line of large multinationals but could generate negative publicity and have a wider impact. Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) issues are on corporate radar screens because of the risk of destroying market value if there is an exodus of investors. Doing business with the military in defiance of sanctions also raises the specter of tarnishing the brand. Norway has announced that it is carefully monitoring sovereign fund investments in beverage giant Kirin due to its partnership with the military affiliated Myanmar Economic Holdings (MEH) while Human Rights Watch has also denounced this joint venture. Kirin says it won’t withdraw from what is regarded as a promising market but is looking for a non-military partner or could try to buy out MEH. This corporate stiff arm of the junta will probably be followed by other firms worried about the consequences of military ties.

Some 50 western firms have signed a statement condemning the coup, including Coca-Cola, Facebook, H&M, Heineken, Nestle, Adidas, Carlsberg, L’Oreal, Maersk, Metro, Total, Telenor and Unilever. Facebook has also banned Tatmadaw-linked accounts and advertising from military-affiliated holding companies.

Approximately 430 Japanese firms operate in Myanmar but only a few have signed the statement condemning the coup. The Nikkei asked the Japanese Chamber of Commerce about its position regarding the coup, but it responded by saying it is still considering its response. Japanese companies have invested over $1.7 billion in Myanmar since international sanctions began easing in 2011 so there is a lot at stake. Human Rights Watch (HRW) urged Japan to join other governments in imposing targeted economic sanctions against the military-affiliated companies, including Myanmar Economic Holdings Limited (MEHL) and Myanmar Economic Corporation (MEC), while nudging Japanese companies to sever any business ties to the military.

This cautious approach prevails among Asian firms. Protestors have taken note and started boycotting some Singaporean brands after Singapore Foreign Minister Vivian Balakrishnan said the city-state should focus on doing business and not weigh in on the politics of the coup.

Utter Nonsense?

Tokyo touts its channels of communication, but it hasn’t got much to show for its connections. Watanabe Hideo, chairman of the Japan-Myanmar Association and Sasakawa Yohei, chairman of the Nippon Foundation, met junta strongman Min Aung Hlaing on the eve of the coup, and both probably have him on speed dial, but neither has a record of calling the military out for extensive human rights abuses and neither is credited with promoting democratization.

Sasakawa is Japan’s special envoy on national reconciliation in Myanmar, and recently brokered a ceasefire in Rakhine, but he has never commented on the military’s brutal campaigns against ethnic groups. Soon after the coup he stated,”If the United States imposes economic sanctions on Myanmar, its ally Japan will be put in a difficult position”. Well that cat is out of the bag as the US has ratcheted up sanctions so Tokyo must be feeling awkward about how to manage the coup and its relations with the Biden Administration which has made clear it wants Japan to act more resolutely.

Ambassador Maruyama Ichiro has gotten a lot of mileage out of a video clip of him engaging demonstrators outside the Japanese Embassy, telling them Japan hears their voice but this is the same official who served as the leading apologist for the military’s brutal expulsion of over 700,000 Rohingya in 2017. Back then he was dismissive of sanctions, calling them “utter nonsense”. In that interview with The Irrawaddy, “Maruyama stressed that the international community, including Japan, has a common goal to help Myanmar’s democratic transition succeed. However, there are differing views about which policy will best achieve that goal.” Indeed, a UN Fact Finding Mission (FFM) recommended that military commander-in-chief Min Aung Hlaing and his subordinates be referred to the ICC for ethnic cleansing and acting with “genocidal intent” against the Rohingya. The ambassador opposed this recommendation and said, “if the Myanmar government attempts to patiently solve the problem, Japan will support it as best it can while listening to the people’s voices.”(emphasis added) It is troubling that the ambassador reassured pro-democracy demonstrators in 2021 using the same words he used while defending the military against accountability in 2018. He has been exceptionally solicitous of the military and as such, it’s hard to imagine he will go beyond perfunctory reprimands in trying to navigate between human rights, democracy and appeasement.

According to Teppei Kasai, Asia program officer at HRW, “As a major and influential donor, the Japanese government has a responsibility to take action to promote human rights in Myanmar. It should urgently review and suspend any public aid that could benefit the Myanmar military.” HRW, along with Human Rights Now, Human Rights Watch, Japan International Volunteer Center, Justice For Myanmar, and Japan NGO Action Network for Civic Space, sent a letter to Japanese Foreign Minister Motegi Toshimitsu, asserting that the coup and bloody aftermath should trigger a suspension of Official Development Assistance (ODA) programs based on provisions in Tokyo’s ODA charter stipulating that aid should be contingent on “consolidation of democratization, the rule of law and the respect for human rights.” The government has announced it will only suspend funding for new projects and instead of imposing any sanctions will try to keep channels of communication open in the hope of finding a resolution to the crisis.

In light of the “escalating bloodbath and atrocities” Maung Maung, a veteran freelance journalist based in Yangon, asserts that “the people of Japan will be sure to have sympathy and listen to the voices of the helpless people and will serve as a driving force for the Japanese authorities to take a right action.” Alas these high hopes have been sidelined by pragmatic accommodation because business and geopolitical interests are driving policy and Tokyo is unwilling to sacrifice anything for its values and principles.

Japan is the OECD’s leading provider of ODA to Myanmar, disbursing US$1.8 billion in 2019, believed second only to China which does not publish figures for its assistance. Thus, the decision to hold off on fresh assistance might have a significant impact. Tokyo may try to soften the consequences for the general public by scaling up humanitarian support through international agencies and nongovernmental organizations. But, as Hitotsubashi University’s aid expert Ichihara Maiko found, almost none of Tokyo’s assistance has been allocated to civil society organizations or towards democratization support.

The pretense of efforts to quietly influence the course of events confronts the reality of Tokyo’s ready acquiescence to the military during the crackdown on monks in the 2007 Saffron Revolution, the annulment of the NLD’s landslide victory in the 1990 elections, the slaughtering of pro-democracy demonstrators in 1988 and General Ne Win’s coup in 1962. Sophia University’s leading Burma expert Nemoto Kei explains that, “Japan was a strong supporter of the Myanmar military during the period of the junta (from 1988 to 2011). Though Japan welcomed the change that occurred in Myanmar in 2011 towards a quasi-democratic system, they continued to keep good relations with the military” in order to sway policies.

Nemoto believes, however, that the Japanese government’s ability to influence the course of events is limited despite close relations with the junta, asserting that, “they still think that they can persuade Min Aung Hlaing to stop rushing ahead their scenario which is to re-hold a general election after evicting Aung San Suu Kyi and NLD from the political arena. However, it seems almost impossible for Japan to change this scenario. They know they cannot do it, but they don’t want to ‘confess’ it to the international community.”

In Nemoto’s view the Chinese bogeyman scenario is exaggerated, “we should not forget that the Myanmar military is not a simple pro-China body. Though they relied on China during the junta period (1988-2011), they were always cautious of China’s over presence in Myanmar.” He adds, “As for Japan’s diplomacy towards Myanmar, it is not wise to only criticize the coup and do nothing” just because it may benefit China. He argues, “Japan should act together with G7 countries, otherwise MAH and the Myanmar military will just dismiss (or disdain) Japan as a country that can do nothing. Japan has to think about sanctions seriously this time.”

Gen Z- Fuck the Coup and Save Myanmar!

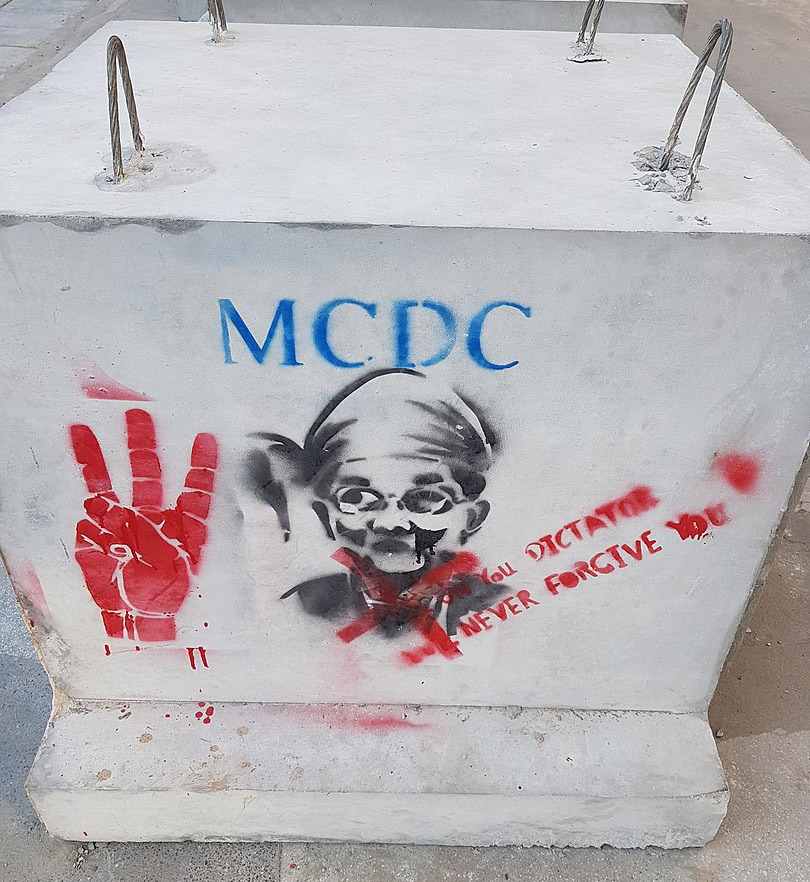

Banners and graffiti expressing this sentiment, along with other gestures of spirited dissent, represent a collective flipping off of the junta by a generation that feels it is being robbed of its future.

The defiant young people of Myanmar standing up to the military have mounted an edgy media-savvy campaign to mobilize international awareness and support. Images and videoclips of the military savagely beating and shooting demonstrators are just a click away for anyone in the world with a mobile phone.

One Gen Z blogger laments, the military,“…never treated us like human beings . We are merely rats to them” and appeals to the international community to, “Let Myanmar people get the taste of being a human and let them know dreams are for everyone . Make them [the junta] know how we feel like under their authority.”

Early on pro-democracy activists posted catchy videos of spiritual mediums, bodybuilders, and beauty queens demonstrating in a pageantry of defiance that reverberated in shares and likes across the global community. They have connected with other youthful pro-democracy movements in Hong Kong, Thailand and Taiwan, raising the profile of the #milkteaalliance.

The Milk Tea movement refers to solidarity among youthful activists across Asia who are resisting democratic backsliding in the region. Recently in Hong Kong, China has decided on a new model of democracy without democrats, the envy of autocrats across the region. In neighboring Thailand, where military intervention derailed democracy in 2014, the pro-democracy movement remains defiant despite other nations resuming business as usual. While the Thai military was careful to minimize casualties, Myanmar’s military has been heedless of the carnage inflicted on pro-democracy activists.

Asked whether the junta might have been inspired by the Thai military coup and the muted Western reaction, Kyoto University’s Pavin Chachavalpongpun, a high-profile Thai intellectual and activist in exile, replied, “Thailand is very different from Myanmar. The stakes the West has invested in Thailand are much greater than those in Myanmar, hence the West can afford to put pressure on Myanmar but not so much on Thailand. You can see now that after the Thai coup, the West only imposed ‘soft sanctions’ whereas what happens in Myanmar draws much more attention and a harsher response from the West.” In contrast to the bloody repression in Myanmar, “the Thai regime tried not to cause deaths in order to avoid an international backlash.” He believes that the Myanmar junta misread the situation and expected it would be easier to consolidate authority, not anticipating such prolonged and widespread resistance.

Over the past decade, social media has taken off in Myanmar and these young netizens understand how to use social media feeds to keep the limelight on the horrors unleashed by the military. People everywhere can sympathize with ordinary citizens calling on the generals to respect the election outcome and to stop trampling on the rights and dignity of the people. In doing so, Gen Z has won admiration for its uncommon courage. Clearly the military did not anticipate such a widespread and sustained uprising, but now it is resorting to the same brutal methods it has used to betray and stifle the hopes and dreams of previous generations. Perhaps Gen Z activists are right that the junta is messing with the wrong generation, but this inspiring bravado is heart wrenching as the bodies pile up and the torturers get busy.

Diplomacy, Disappointment and Democracy

Voicing the outrage of Myanmarese across generations, Thant Myint U, a celebrated writer and grandson of former UN Secretary General U Thant, tweeted on March 3,” Inexcusable killing and wounding of unarmed protestors by security forces using automatic weapons, in Yangon and across Myanmar …with every possibility of escalating violence.”

This military mayhem has been the shared experience of ethnic groups across the nation over the past seven decades. Having endured prolonged military campaigns, it is not surprising that many ethnic groups are supportive of the protests. Chiang Mai University’s Ashley South notes, “The protests have seen an important emerging alliance or coalition between NLD members and activists, ethnic nationality individuals and groups, and the “Gen-Z” youth.”

Myanmar’s envoy to the UN, Kyaw Moe Tun, denounced the coup in a passionate speech to the General Assembly and called on the international community, “to use any means necessary to take action against the Myanmar military and to provide safety and security for the people of Myanmar”.

The regime fired him, but his designated replacement resigned rather than follow orders and now the issue of UN representation remains in limbo because the coup government lacks any legitimacy. The G7 and EU joined in condemning the coup and called for a restoration of democracy.

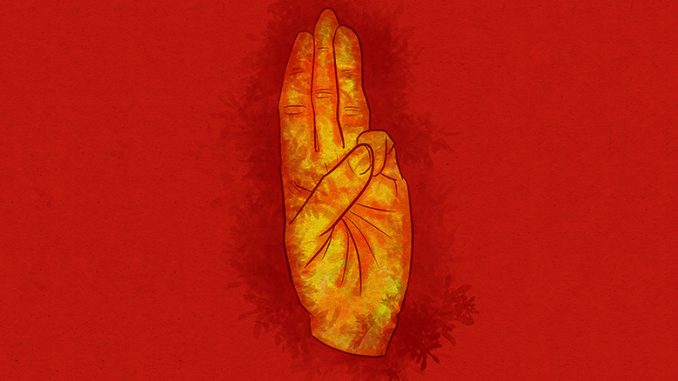

Myanmar’s UN envoy gave the three-finger salute of defiance that protestors have adopted from the Hunger Games where it was a sign of solidarity among rebels resisting tyranny. This same salute, now banned, was ubiquitous among pro-democracy demonstrators in Thailand following the 2014 military coup.

A number of Myanmar-based contacts urge UN military intervention based on the Responsibility to Protect (R2P). The BBC captured a scene from Yangon in early March of a large illumination of R2P spelled out by innumerable candles lit by hopeful demonstrators. Nyo Nyo Thinn, founder of Yangon Watch and former member of the Yangon Regional Parliament, observes, “With the brutal crackdown, the public is resentful and hopeful of military intervention from the international community. They hope the UN will invoke R2P but realistically I don’t see this happening. Unfortunately, more and more lives will be lost.” She adds, “China has influence on the junta and has to be pressured regionally by ASEAN/Japan to push for meaningful negotiations aiming for a win-win outcome.” What that win-win scenario would look like remains unclear.

Ma Thida, a novelist and former political prisoner, knows military intervention is unlikely but still, like many others in Myanmar, she hopes: “As you can see, people can’t expect any legal or proper protection from anyone else, especially from the police and army. The judiciary system is also not defending citizens. So the international community should seriously think about its responsibility to protect.” She also calls for referring the coup leaders to the ICC, hopeful that this might convince them to change tactics and refrain from more extensive repression.

Wai Moe, a veteran journalist who has reported for the New York Times, is scathing about the global response saying, “The state does mass killing indiscriminately while the world is watching but the international community is still providing hopelessness to the people of Burma.” In addition to supporting sanctions that target military business interests and more pressure from Tokyo, he also calls for more robust intervention because, “The military only listens to military power.”

In contrast, Soe Myint Aung, calls on the international community not to raise the expectations of demonstrators, and instead “support the quiet diplomacy of ASEAN.” For many observers, that amounts to a deafening silence. He adds, “Things will not be the same. We cannot really go back to the pre-coup stage”, maintaining that, “mediation between ASSK and the military is the only way out” and, “saving Myanmar means trying to achieve short-term realizable goals which is mainly about damage control.” Myanmar, in his opinion, is on the brink of a “massive setback scenario where the military suffers from sanctions, the NLD faces a post-ASSK survival crisis and the people face both the collapse of the economy and state failure.” He thinks that it is wishful thinking to imagine that the ongoing civil disobedience movement (CDM) will bring down the regime.

Perhaps he is right, but in Why Civil Resistance Works (Columbia 2011), Erica Chenoweth and Maria Stephan make a compelling argument that non-violence is more effective than violent resistance because it lessens obstacles to moral and physical involvement and leads to higher levels of participation. Wider engagement boosts resilience, tactical innovation, and civic disruption. Nonviolence is also more likely to sow division among opponents, including members of the military establishment. They also conclude that successful nonviolent resistance movements lead to more durable and inclusive peace and democracy. In today’s Myanmar we have seen society rally in support of the CDM, providing material and moral support as civil networks mobilize like-minded people and distribute necessities as they did in the wake of Typhoon Nargis in 2008. But the military has shown no mercy to CDM participants, looting food, fuel and money provided by support networks. Moreover, there are no signs of mutiny because the entire institution is implicated in the bloodshed and fear of accountability is the glue of unity. The junta is ruthless because it knows that it, “is either in power, in prison, in exile, or worse. “

Aung Zaw, editor of the Irrawaddy English language journal on Myanmar, acknowledges this ruthlessness but believes, “The opposition to the illegitimate coup, and the military’s and police brutality are very strong.” Emphasizing the military’s responsibility for this dire state of affairs, he cautions China and Japan against conferring legitimacy on the junta, “and if they do, they will be condemned forever in Myanmar.” The people have taken great risks and sacrificed blood, he says, because “they don’t want to be slaves of the military again.” Maung Saungkha, a freedom of expression activist, adds, “We know that we can always get shot and killed with live bullets but there is no meaning to staying alive under the junta so we choose this dangerous road to escape.”

While inside Myanmar and in the international community there is considerable support for targeted sanctions against the military, as a gesture of solidarity that ensures the butchers of Burma pay a price, there is concern about the impact on a nation already reeling from the pandemic. Thant Myint U cites a late 2020 survey in which the percentage of the population making less than $1.90 a day rose from 16 percent in January to 63 percent by September 2020, with more than a third reporting no income that month.

The implications are stark but underscore that Myanmar faces a range of challenges beyond restoration of democracy. The legacies of military corruption and miserable governance–glaring inequalities, the pathologies of poverty and shrinking opportunities for youth– represent the kindling of discontent the junta ignited in its power grab. Calling for release of political detainees and respect for human rights, Thant argues, “It’s correct for foreign governments to stand against a new dictatorship in Myanmar” but he counsels against the type of sweeping sanctions that might cause economic collapse. He warns, “A desperately poor and unequal country at war with itself won’t produce anything other than a facade of democracy. The aim should be …a fairer and more democratic society for all of Myanmar’s people.”

Article 19’s Matthew Bugher, also cautions that, “International donors need to recalibrate their aid to Myanmar. Obviously, any direct aid to the military-led government should be discontinued. However, donors should ensure that support to civil society and pro-democracy groups is continued and augmented. Donors will need to be flexible in their approach, given the extraordinary challenges faced by civil society groups. They will have to relax their rules and adjust their methodologies. There is a danger that donors look at the highly fraught situation in Myanmar and pull the plug on funding to civil society because it is the easiest thing to do. That would be devastating.”

Bertil Linter concludes,” China, after all, might have welcomed the coup. But neither the Myanmar military nor the Chinese had anticipated this kind of nation-wide mass movement against the coup. And it is not in China’s interests to see Myanmar descend into instability and chaos, so if the protests continue in one form or another, China might intervene diplomatically and help find some sort of compromise that would suit both sides.” Yet, more ominously, he warns, “But even if, even if, they did that, is a compromise possible after what Myanmar’s security forces have done? Shooting and killing unarmed demonstrators, many of whom are teenagers? Arresting and beating others and even going into people’s homes and robbing them of money and possessions? That’s the big question.“

Conclusion

Myanmar is under siege from its own military, ostensible patriots who have pushed the nation to the edge of the abyss. Military rule has not worked out well for the Burmese or Myanmar’s multiple ethnic groups; the nation’s best years came only after the top brass agreed to loosen their grip and establish a tightly tethered democracy a decade ago. The junta is now holding the people and democracy hostage to their vainglory and avarice. How can the international community effectively support the people to overcome this calamity while also addressing the broader challenges of a society living on the edge? Mitigating the gathering humanitarian crisis, and restoring democracy, are crucial priorities. Global actors should not abet the military’s reimposition of a stranglehold that is currently destabilizing the nation and causing the economy to implode. There should be no actions or gestures that confer legitimacy on the junta because it has precipitated this crisis. Myanmar has an elected legitimate government with a massive mandate, and it should be restored to power, not compelled to make concessions to usurpers who have sabotaged the constitution and scuttled the rule of law. It’s naïve to imagine there is any sustainable solution that doesn’t win the trust of a battered Gen Z, key stakeholders in Myanmar’s future, and that requires accountability.

Cover image: Peaceful Salute by @toraillustrates reproduced with permission. See more work from toraillustrates on Instagram, and online: https://toraillustrates315.wixsite.com/mysite