It has never happened before: all the MPs elected from Pattani, Yala and Narathiwat in Thailand’s 24 March 2019 elections were Malay Muslims. 1 Thailand’s Deep South, overshadowed by an insurgency that has claimed more than 7000 lives over the past sixteen years, has a political microclimate all of its own. 2 In earlier decades, this Muslim-majority region was mainly represented in parliament by Buddhists. Malay Muslim members of Thailand’s House of Representatives inhabit troubled terrain, viewed with mistrust by the authorities who may suspect them of being linked to violence, yet regarded as traitors to Malay-ness by some members of their own community.

Unlike voters in the upper South, where the Democrat Party has long been dominant, Malay Muslim voters in the lower South are awfully fickle. Of the eleven parliamentary seats in the three provinces, nine were won by brand-new parties in 2019, and only three by former MPs from the previous parliament. 3 While the Democrat Party won 10 of the 11 seats in 2011, it secured only a single constituency, Pattani District 1, in 2019. The biggest winner in the region was the new Prachachat Party, led by former house speaker Wan Muhamad Noor Matha (aka Wan Nor), which gained six seats, two in each of the three provinces. Another three seats were taken by the new Palang Pracharat Party, which enjoyed close ties to the military junta that had seized power in the May 2014 coup d’etat. A single constituency seat, Pattani District 2, was won by the pragmatic Bhumjai Thai Party, which had won a different Pattani seat in 2011. Apart from the eleven constituency seats, three other Malay Muslims secured party list seats: Prachachat leader Wan Nor, Petadau Tohmeena for Bhumjai Thai, and Niraman Sulaiman from Future Forward. What had happened?

******

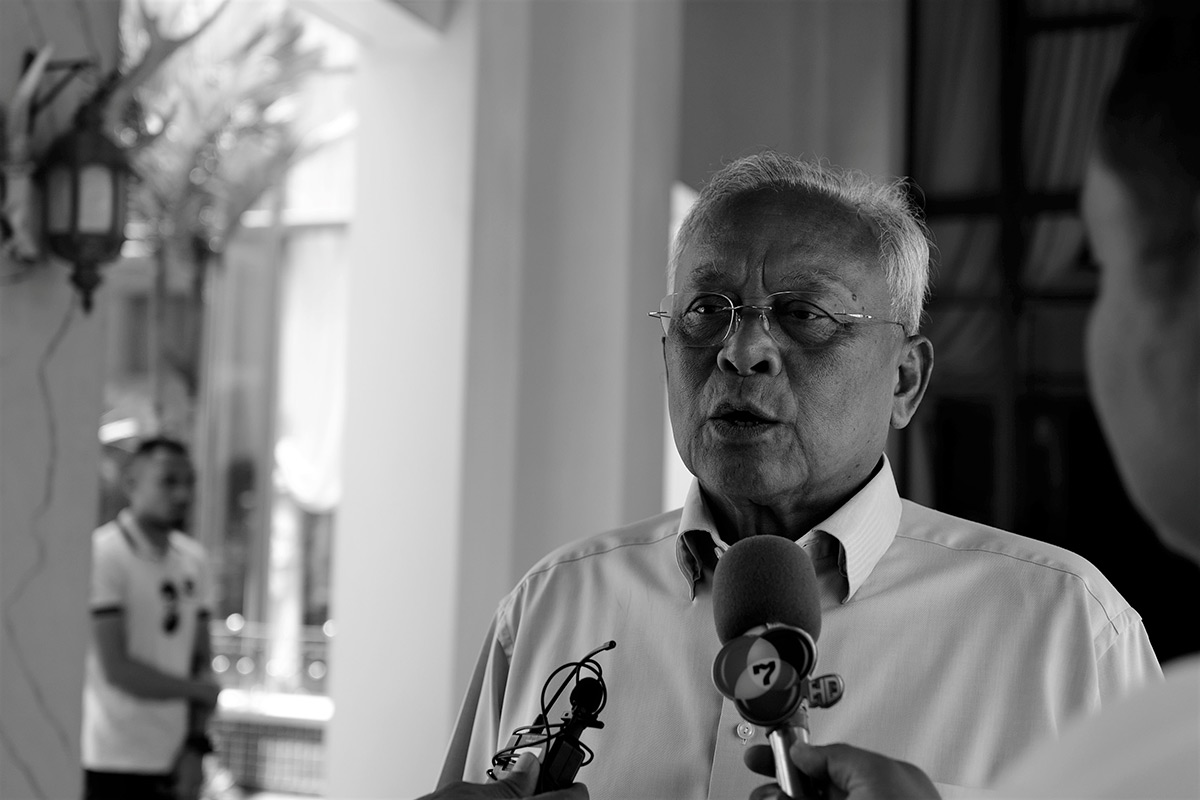

Wan Nor is an enigmatic figure: by far the most successful politician to emerge from the Deep South, this former holder of many great offices of state is soft-spoken, reserved and intensely private. A bachelor, Wan Nor lives alone in a palatial house in Yala, rarely granting interviews – and never to me. Together with Den Tohmeena and others, Wan Nor created the Wadah (‘unity’) political faction in 1986 – an organized attempt to promote Malay Muslim interests in the national parliament. Wadah migrated from party to party in search of opportunity and advantage, thriving under the patronage of Chavalit Yongchaiyudh’s New Aspiration Party, and later Thaksin Shinawatra’s Thai Rak Thai. Under successive governments between 1995 and 2005, Wan Nor was Bangkok’s principal point-man in the region, and was amply rewarded for his services.

Wan Nor’s undoing took place on the terrible night of 25 October 2004, when over a thousand unarmed demonstrators were rounded up at Tak Bai and transported to a Pattani army camp in military trucks. Seventy-eight men suffocated during the drive. Despite serving as Minister of Interior at the time, Wan Nor had been powerless to prevent the loss of life. Blamed by voters for the Thaksin government’s heavy-handed security policies, all Wadah’s constituency MPs lost their seats in the 2005 election. The Prachachat Party was Wadah’s latest attempt at a comeback, after spending fourteen years in the political wilderness.

Oddly, however, Prachachat was the brainchild not of Wan Nor, but of Tawee Sodsong, a Buddhist ex-police colonel who had previously headed the Southern Border Provinces Administrative Centre, and was still on a personal mission to transform the region. Wan Nor initially declined to serve as party leader, and on the campaign trail he was largely absent. When I met him at a big Prachachat rally in Pattani, he looked strangely vacant.

Prachachat did well to secure six constituencies, but Wan Nor’s party was helped by feuding rivals: some former Democrats defected to Suthep Thuagsuban’s breakaway Action Coalition for Thailand, while others switched to the military-aligned Palang Pracharat. Nor did Prachachat win any seats elsewhere in the country, failing to broaden its appeal beyond Malay identity to a multicultural national electorate. At 75, Wan Nor found himself back in the parliament over which he had once presided, this time leading a tiny opposition party that looked destined for permanent marginality. He seemed like a man who had lost heart for the fight.

When I asked Tawee during the campaign whether Prachachat was committed to opposing the military in the new parliament, he was a little evasive. It was widely rumoured that Wan Nor was willing to join the Prayuth Chan-ocha government. After all, his whole career had been based on pragmatism and compromise. In the end, Prachachat did not sell out, but other prominent Malay Muslims made different choices in 2019.

******

When Petdau Tohmeena finally entered parliament in 2019, it was after many years of trying. What took her so long? Petdau is a Pattani-born, Malaysian-trained medical doctor, the granddaughter of Haji Sulong, a legendary Islamic teacher and Patani nationalist who was murdered in the 1950s. Her father, Den Tohmeena, first entered parliament in 1976 under the Democrat banner and co-founded the Wadah group a decade later. Den was in parliament for the next twenty years, briefly serving two stints as a deputy minister, then later becoming both an elected senator for Pattani and Secretary General of the Islamic Council of Thailand. I followed Petdau’s own Senate campaign in April 2006: despite her impeccable cultural capital, she was narrowly defeated by Anusart Suwanmongkol, a wealthy Buddhist autodealer and hotelier, in an eighty per cent Muslim province. Petdau’s 2006 Senate defeat ushered in a thirteen-year electoral banishment for a family that had previously dominated Pattani politics for four decades.

The Tohmeena dynasty inspires mixed feelings: while Haji Sulong is revered, Den is a divisive figure, long at odds with most of his old Wadah comrades. The founders of the Prachachat Party bypassed Den, inviting him to become a senior advisor only after setting up the party without him in 2018. But Wan Nor and Tawee beat a path to Den’s door in vain: he had already done a deal with the ultra-pragmatic Bhumjai Thai Party. The price for securing Den’s support? A number 11 spot on the Bhumjai Thai Party list for his daughter Petdau. During a gathering at Den’s home to mark Haji Sulong Day on 13 August 2019, the family clan was gleeful that a Tohmeena was back in the National Assembly.

Founded in 2008 by Newin Chidchob, a political svengali and kingmaker from the northeastern province of Buriram, the Bhumjai Thai Party was quietly positioning itself to join whatever government might emerge from the 2019 elections. Bhumjai Thai had no compelling policy initiatives relating to the region. Locals were mortified when party leader Anuthin Charnvirakul opened an election rally in Narathiwat with calls for the legalization of marijuana – hardly a vote-winner in this conservative Muslim-majority area. This problematic policy was one of the reasons former Pattani Bhumjai Thai MP Sommut Benjaluck defected to Prachachat in 2019. Another Pattani Bhumjai Thai candidate, Abdul Korha Waeputeh, told me that they never mentioned legalizing cannabis in their campaign activities. Petdau admitted to me that she had been vilified on social media when, as a Bhumjai Thai MP, she voted for General Prayuth to become prime minister. How could a family that claimed to embody Malay identity select a premier from the Army, widely distrusted in the region? Petdau’s long-held dream to enter parliament had come true only because of a Faustian pact, under which she endorsed the de facto continuation of the existing military regime.

******

Adilan Ali-is-hoh, who took Yala District 1 for the military-aligned Palang Pracharat Party, was an even more surprising election winner. Adilan was a prominent human rights lawyer and leading figure in the Muslim Attorneys’ Centre (MAC), well known for defending numerous insurgent suspects. Why would such an apparently progressive figure run for election under the banner of an ad hoc party, assembled purely to ensure that Prayuth could stay in the premiership after the election? To confuse matters further, Adilan’s two closest MAC colleagues ran for different parties in the same election: Abdul Korha Waeputeh contested Pattani District 3 under the Bhumjai Thai banner, while Kamsak Leewamoh won Narathiwat District 4 for Prachachart. When I visited his office afterwards, Adilan’s explanation was a bit difficult to follow: he claimed that running under different party banners was a deliberate political strategy of diversification, to ensure that Malay Muslim interests would be represented in the next government. Adilan’s political philosophy boiled down to ‘If you can’t beat them, join them’. But he admitted that many of his former colleagues from the human rights community had disowned him after he joined Palang Pracharat.

Adilan conceded that he had been approached by military officers to join the party, but insisted that he had not received any state funding, and had not held meetings with any government officials during the election campaign. The party had not staged any rallies in Yala, and he had not appeared on Palang Pracharat rally platforms in neighbouring provinces because he did not want to criticize other parties or candidates. Adilan’s critics argued that his actions smacked of opportunism rather than strategy: trading on his reputation as a grassroots legal activist, he had sold his services to the military. Nevertheless, Adilan was extremely charming and persuasive. When he was talking to me, I found it impossible to disbelieve him. But after leaving his office I struggled to make sense of the stories he had told me.

I followed long-time Democrat MP Anwar Salae on the campaign trail on 20 March. In the lobby of Anusart Suwanmongkol’s CS Pattani Hotel, where former prime minister Chuan Leekpai was staying, were half a dozen young security guys with military haircuts in black uniforms, sporting high-tech radio earpieces. But their uniforms had no insignia, and they wouldn’t tell me who they worked for. Anwar was waiting in the lobby as well, with me and the black-clad mercenaries – not invited up for breakfast with the cabal in Chuan’s suite? Although the Democrats’ best electoral hope in these parts, he remained an outsider in a party dominated by Buddhists from the ‘other’ South, above the border with Songkhla. I’d met Anwar a few times before, but that day he looked distinctly uncomfortable and did not want to talk much.

Chuan remained extremely popular with Buddhist voters in Pattani, who turned out to greet the slightly frail 80 year old, as the Democrat campaign truck and the eight car motorcade weaved through the busy downtown streets. For whatever reason, Chuan’s promised walk through the market never took place. At the last stop, he gave a short speech: the military took power because politics was dominated by bad people, Thaksin, Yingluck and others, at all levels. The answer was to choose good people like Anwar in this election. I didn’t hear this former firebrand of the left say a word said against the ruling junta.

In the end, Anwar and Chuan both did well: Anwar saw off his Prachachat rival to win the district comfortably, and Chuan ended up as speaker of the house, Wan Nor’s old job. But otherwise the Democrats fared badly, literally decimated in the Deep South.

******

These were strange times for Malay Muslim voters. Who could they trust to represent them? Was it better to work with the military and the conservative establishment, or to vote for the politicians most likely to resist domination from Bangkok? In the past, the people of the Deep South had flipped between voting for Thaksin and voting Democrat, but both insurgent violence and state repression continued, and their marginal place within the Thai state persisted. The March 2019 election offered no clear answers to the region’s seemingly intractable political problems. Was Wan Nor any better than Petdau, or Adilan any better than Anwar? After the intense excitement of the election campaign – the first time in years that large public events had been staged in Patani after dark – expectations were once again low.

Duncan McCargo

Duncan McCargo is Director of the Nordic Institute of Asian Studies and Professor of Political Science at the University of Copenhagen.

E-mail duncan@nias.ku.dk

This article draws on fieldwork observations and interviews conducted in Pattani, Yala and Narathiwat in March and August 2019. The author gratefully acknowledges financial support from the United States Institute of Peace, Grant SG-477-15.

Notes:

- For an overview of the 2019 election, see Duncan McCargo, “Democratic Demolition in Thailand’, Journal of Democracy, Vol.30, No.4 (2019): 119–133. ↩

- On politics and the insurgency in the Deep South, see Duncan McCargo, Tearing Apart the Land: Islam and Legitimacy in Southern Thailand, (Ithaca NY and London: Cornell University Press, 2008), especially pp. 63–80. ↩

- For a discussion and results of the 2019 elections in the southern border provinces, see Daungyewa Utarasint, “The Deep South: Changing Times”, Contemporary Southeast Asia, Vol.14, No.2 (2019): 207–215. ↩