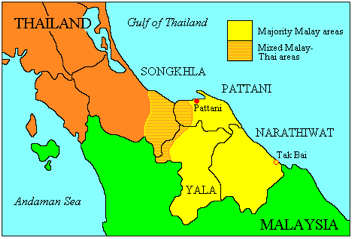

On 20 January 2020, Thai negotiators and members of the Barisan Revolusi Nasional (BRN), the separatist movement that controls virtually all of the combatants in Thailand’s Muslim-majority, Malay-speaking south, joined in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, to announce that they have started the much-awaited peace talks. According to Thai and BRN officials, this latest peace initiative was the first that the secretive BRN’s ruling council, known as the Dewan Pimpinan Parti (DPP), had actually given their negotiators the full blessing to come to the table. It was presumed that the two sides are there to seek a political solution to this intractable conflict that resurfaced in Thailand’s Malay-speaking South in late 2001 but was not officially acknowledged until 4 January 2004, when scores of armed militants raided an army battalion in Narathiwat province and made off with more than 350 pieces of military weapons. The previous wave surfaced in the early 1960s in response to Thailand’s policy of assimilation that came at the expense of the Patani Malays’ ethno-religious identity. Armed insurrection died down in the late 1980s but the narrative – one that says Patani is a Malay historical homeland and that the Thai troops and government agencies are foreign occupying forces – never went away.

But 20 January 2020, was not the first time that Thailand has publicly announced that they are coming to the table with the BRN to settle the conflict through negotiation. The then government of Prime Minister Yingluck Shinawatra had launched a similar initiative on 28 February 2013, also in Kuala Lumpur. The announcement caught all the key stakeholders off guard. They include the BRN and the Thai military. BRN did eventually send representatives to the table — the former foreign affair chief Muhammed Adam Nur and a member from its youth wing Abdulkarim Khalid. But their job was to derail the process, which they succeeded in doing so by the last quarter of 2013, by which time Yingluck was running for her political life from the so-called Shut Down Bangkok street protest that paved the way for the May 2014 military coup that ousted her from power. In spite of being something between a hoax and a big leap of faith, Yingluck’s initiative generated a great deal of excitement and great expectation from the local residents in the far South. After all, it was the first time that a Thai government had publicly committed itself to resolving the conflict politically. Unfortunately, peace for this historically contested region was not the main motivation. Yingluck and the then Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak were more interested in raking the political benefits of a peace initiative.

In the aftermath of the May 2014 coup, there was some serious debate over whether to continue with what Yingluck had started. The National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO), Thailand’s top brass behind the coup, had no part in the talks or its inception. But the junta decided to continue with the talks but on condition that the talks would be inclusive. In other words, all the Patani Malay separatist groups – BRN, all Patani United Liberation Organisation (PULO) factions, Gerakan Mujahidine Islam Patani (GMIP) and Barisan Islam Pembebasan Pattani (BIPP) – would have to come together and negotiate their differences with the Thai State. Prayuth Government and Thailand’s top brass were irritated by the very idea of “lowering themselves” to talk to Patani Malay rebels, thus, the demand of inclusivity. They wanted to get it done and over with, and once-and-for-all was their attitude. In December 2014, seven months after the coup, Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-ocha went to Kuala Lumpur to introduce the newly appointed chief negotiator, Gen. Aksara Kherdphol. He was to work hand-in-hand with Malaysia’s former spy chief, Dato Sri Ahmad Zamzamin bin Hashim, the designated Facilitator for the peace process.

In line with Thailand’s request of inclusivity, with the help of Malaysia’s Facilitator, MARA Patani became the umbrella organization under which all the Patani Malay long standing separatist movements would come under. The problem with this arrangement is that the BRN, the one group that control the combatants on the ground, refused to join. Nevertheless, the process stubbornly limped along, hoping that the initiative could generate enough traction to attract the BRN’s participation. And so for three years, Thai negotiators, MARA Patani and Malaysian Facilitator worked on the so-called Safety Zone, a pilot project that would turn a provincial district in the far South into a cease-fire area with development projects to serve as a model that peace and development can be achieved with the absence of violence. But in reality, it was much ado about nothing because the one group that controlled the combatants on the ground wasn’t part of the process.

In October 2018, the government of Gen. Prayuth Chan-ocha replaced Gen. Aksara with Gen. Udomchai Thamsarorat, a man with many years of experience on the battlefield in the far South. Udomchai moved quickly to distance himself from the Safety Zone Project knowing that it would fail without the participation of the BRN. Udomchai’s appointment came two months after the newly elected government of Dr. Mahathir Mohammed had replaced Dato Zamzamin with retired police chief Tan Sri Abdul Rahim Noor as the Facilitator. Udomchai thought he could count on the new Malaysian facilitator to pressure the DPP to the table. But that backfired when militants on the ground retaliated with a spike in violence in January 2019 with the murder of two Buddhist monks in Narathiwat. The same month also saw insurgents gunning down four civil defense volunteers (local hired security details employed by the Ministry of Interior). A retired public school teacher was also shot dead and hung; his vehicle was stolen and used as a car bomb later that day.

Local political activists such as The Patani and The Federation of Patani Students and Youth (PerMAS) stepped up their campaign on the ground, calling on BRN combatants to respect international humanitarian law and norms, reminding the insurgents that, as non-state actor with limited conventional military capability, BRN’s ultimate goal is political in nature. Insurgents responded positively to the idea of taking the moral high ground in their fight against the Thai State and backed off from the soft target. About six months later, Thailand and Malaysia applied more pressure on the BRN leadership to come to the table. This time around, BRN responded with a series of small bombs through out Bangkok, humiliating the Thai government who was hosting of ASEAN foreign ministers who were in the capital for a series of bilateral and multilateral meetings with their Dialogue Partners, including the United States, Japan and China.

Again, Malaysian facilitator and Thai negotiators backed off. At this point in time Bangkok is convinced that Rahim Noor and his team of Facilitators were not able to get the BRN leaders to the Thai side. And so the Thai negotiators began to reach out to a foreign INGO who had worked with BRN in the past knowing that Malaysia would object to the very idea of bringing in an outsider into the process. BRN’s leaders, surprisingly, permitted their Foreign Affairs Committee, led by Anas Abdulrahman (also known as Hipni Mareh), to meet with the Thais. The two sides met in Indonesia and then in early November 2019, in Berlin, Germany, where a seven-page TOR drafted by the foreign INGO, was presented to the Thai and BRN negotiators. Needless to say Kuala Lumpur was not pleased with being kept in the dark the whole time. As for the foreign NGO who organized the meetings in Indonesia and Germany, it was an opportunity to get back into the game after they had been told to stay out after Bangkok gave the mandate to facilitate the talks to Kuala Lumpur in 2013.

Thailand’s effort to mend the fence with Malaysia came in form of a public announcement, an event to launch a breakthrough in which Malaysia is to be credited for its hard work. This so-called breakthrough was launched on 20 January 2020, in Kuala Lumpur. It was full of praises for the Malaysian government. But deep down inside, all parties knew that the direct talks with the Thais in Indonesia and Berlin, and 20 January launch in Kuala Lumpur as a big leap of faith. This secretive movement that had been antagonising the Thai security forces for the past 17 years is drifting towards an uncharted territory. The military wing and the combatants on the ground were extremely uncomfortable with the ideas, partly because they weren’t consulted from the start and partly because they just outright disagree with the idea of setting the stage for a formal peace process when their demands were not being addressed. Moreover, the combatants on the ground were told by their commanders that their struggle to liberate this Malay homeland known as Patani was wajib, a moral obligation. Is it still a wajib? No one seems to know.

In its latest report on the conflict dated 25 January 2020, “Southern Thailand’s Peace Dialogue: Giving Substance to Form,” the International Crisis Group (ICG) said for the peace process to succeed, BRN needs to articulate the kind of future it envisions for the region and the Thai government should rethink its policy of not permitting international observers into the process. Both Bangkok and Kuala Lumpur should accede to impartial third-party mediation. In short, said ICG, the process needs a reboot.

The problem with foreign facilitators and mediators – many have come and gone over the past 17 years – is that they see Malaysia as their competitor instead of a stakeholder in the conflict. Malaysia is much more than just a “facilitator” or “mediator” but a stakeholder with real security, diplomatic and political concerns. In fact, none of the peace initiatives for Thailand’s far South since 2004 involved the use of honest broker. Still, many are asking why the BRN’s ruling council had permit its Foreign Affairs Committee to come to the table with the Thais without consultation with the militants on the ground and other division leaders. Some members said these secretive leaders took comfort in knowing that these negotiators were put on a very short leash and that they could be recalled any moment.

Senior Thai security officials believe the political wing knew that the powerful military wing would be dead against the idea of starting a formal peace process with the Thais and therefore, had to go to Indonesia and Germany without their consultation. Unlike other revolutionary or independent movements, BRN’s so-called political wing is still very weak and inexperienced. Thai policymakers never invested time into thinking about the consequences of rushing the BRN negotiators to the table. Like the BRN, the Thai side didn’t consulted among themselves, much less work together to formulate a strategy for a possible peace process. In fact, the actions and activities of the Thai Army on the ground suggested that they could careless about the development on the political side of the equation.

Long range reconnaissance patrol, mop up operation against BRN cells on the ground were being carried out as far back as January 2020, even when BRN was making positive gesture, like acceding to the Deed of Commitment with Geneva Call, an international NGO that work with armed non-state actors across the globe to promote rules of engagement and humanitarian principles. BRN also announced in early 3 April 2020, that it would end all hostilities as part of their humanitarian effort to help contain Corvid-19. BRN also urged the public to comply with the directives from the public health officials. On April 30, Thai security forces killed three BRN combatants in Pattani. Fearing that the cells on the ground would retaliate, BRN quickly reiterated its earlier position and instructed its combatants and the general public that the unilateral ceasefire must stay the course. Three days later, on May 3, 2020, in Sao Buri district of Pattani province, two Paramilitary Rangers were shot dead at close range by gunmen on a motorbike coming from behind and commence fire.

All fingers pointed to the BRN but the movement’s leadership kept quiet. To say that they had given the green light to take out the two Rangers in realisation for the shooting death of the three combatants would amount to an end of the ceasefire, an initiative by the political wing to show the powerful military side that they can generate legitimacy and praises for the movement. To say that the gunmen were BRN combatants who acted without order from the commander is to say that the movement doesn’t have adequate command-and-control on the ground. And not to say anything at this juncture, after surfacing publicly to jointly announce with the Thais negotiators, would also harm their credibility and integrity.

Don Pathan

Don Pathan is a Thailand-based security analyst.