In 2011, a Children’s Day Fair was held in La Meng 1school in the Raman district of Yala province. The fair consisted of a variety of activities including games, shows, gift drawing lots, eateries and goodies giveaways, and an award granting ceremony. In addition to a “mountain of gifts” from several state agencies and the military, what was special about that year’s fair was a schoolchildren’s “Rayo Kito” (or “Raya Kita” in standard Malay, which means “Our King”) singing show. The song described how dedicatedly and tirelessly the king worked for his subjects, and how much in return his subjects loved and revered him. To sing the song in the Children’s Day Fair is to convey the message that Malay Muslim schoolchildren are grateful to and love the king like others in the country, regardless of their ethno-religious difference.

Busa, a father of a Grade 5 schoolchild, commented that, although the Children’s Day Fair had gained a lot of support from state agencies since the eruption of the ongoing unrest in 2004, it had also been closely monitored by the state. Soldiers came in an APC and a military pick-up truck not only to give gifts and ice-creams, but also to check if the activities were in line with security policies. Schoolchildren in turn sang the song “Rayo Kito” to show that they loved and were loyal to the king and the country following the state’s request. He therefore added that the show could not be taken at face value, explaining that, whilst some students may have respected the king as the song recited, others did not really pay attention to the lyrics and merely sang because they were told to do so.

Malay Rajas

La Meng residents regard Malay Rajas (or Raya) as charismatic and mighty figures. One story that circulates among them has it that, while traveling in the forest with his followers, a Raja ran into an elephant that tried to attack him. With his might, the Raja defeated the elephant with his bare hands. The story spread widely and made the Raja a daunting figure. In addition, given their association with the supernatural, Rajas need to observe some dietary rules. They cannot eat bamboo shoots and some kinds of fish, or otherwise their power will disappear. And, because they are both charismatic and mighty, they provoke love and fear in their subjects.

Meng, a Malay cultural expert, said the residents are ambivalent to Rajas. Villagers have positive attitudes toward Raman rulers, and especially Tok Ni, who is known to have played an important role in founding the village. When they hold rituals for their ancestors and other spirits, they always pay respect to Raman rulers. Yet their ancestors were scared of some Raman rulers because of the latter’s cruelty. One story goes that Raya Sueyong, who fled Kedah and married a Raman ruler’s daughter, always ordered his chefs to prepare dishes that included the flesh of some of his subjects. Another story has it that a Raman ruler, noticing that part of a jackfruit presented to him was missing, asked soldiers who had taken it. After knowing that a pregnant woman ate it because of her morning sickness, he ordered soldiers to cut her belly open to take jackfruit out. Similarly, he had the legs of a concubine amputated when he learned that she had sneaked out of his court.

Meng added that Malay subjects’ fear of Malay rulers extended to Siamese kings. He said that “Malay subjects feared Siamese kings too because the kings lived far away and they had never seen them. They didn’t know what the kings were like. Moreover, a Siamese king once sent Khun Phan to the region to defeat Malay bandits, and this made local Malays fear Siamese kings even more.” If Meng’s narrative is correct, then the question is why present-day Malays love Thai kings, and especially King Bhumibol.

Thai Kings 2

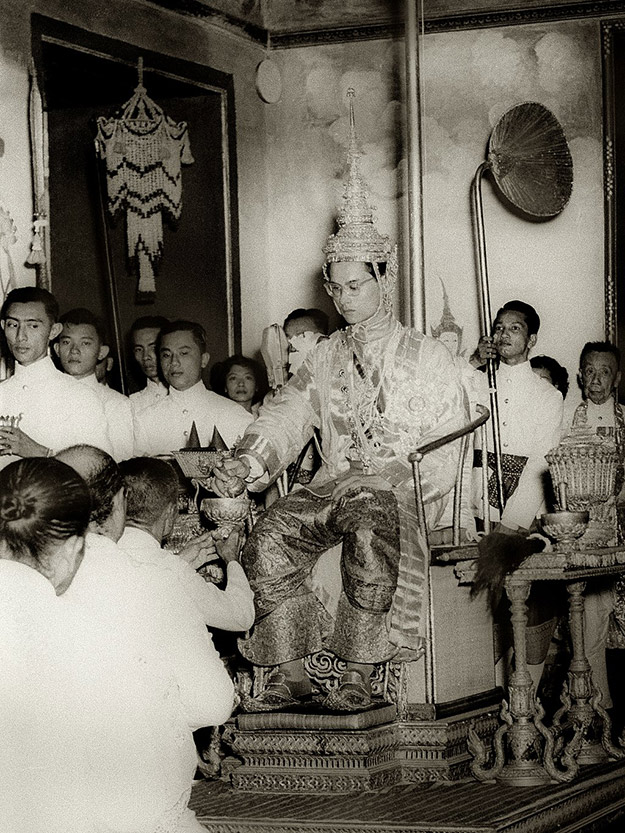

As soon as the borders of Siam were demarcated, its ruling elites were preoccupied with finding ways to connect peoples of different ethnicities and religions within the territory. Doing so was particularly important as the French utilized a racial justification for expanding their control over the Lao and Khmer who they claimed belonged to French Indochina. Faced with such logic of race, King Rama V and his advisers advanced that peoples living within Siam belonged to the Thai nation as long as they met certain criteria – especially being loyal to the king. Although King Rama V’s “inclusive” nation-building project was discontinued during the reign of King Rama VI and through the reigns of King Rama VII and King Rama VIII because of the country’s political changes, it resumed in the reign of King Rama IX or King Bhumibol.

King Bhumibol was promoted as transcending all ethno-religious differences. Although a Buddhist, he was constitutionally the Upholder of Religions – including Islam. As a result, whilst Islam finds it difficult to fit in the “religion” category of state ideology because of the latter’s strong associations with Buddhism, it finds support and protection in the “monarch” category. Likewise, although an ethnic Thai, he was constitutionally the Head of State, and, more recently, had been known as the Father of the Land, whose benevolence supposedly extends to all citizens regardless of their ethnicity. Whilst Malay ethnicity finds it not easy to fit in the “nation” category of state ideology because of the latter’s association with Thai ethnicity, it can similarly find support and protection in the “monarch” category. This category therefore makes it possible for Malay Muslims to reside within the territory of the Thai-Buddhist state, which is notorious for its ethno-religious discriminations, as in the case of La Meng residents.

Meng said that, in addition to their familiarity with Malay Rajas, the reason why the residents found it not difficult to respect King Bhumibol had to do with how they perceived him. Although the residents in general were indifferent to King Bhumibol, they did not feel oppressed under his reign. They may have disliked state authorities – especially security authorities – but they did not associate either such authorities or the government to the king. Kak Dah, a member of numerous state-supported groups, claimed she did not think that the king was discriminatory in terms of ethnicity and religion, although she found that certain state authorities were. She also added that “it is not only Thais who love the king. Malays too love the king”. Asroh, a Grade 6 schoolboy, claimed that he had no problem with the king because “the king is good to us Malays. He is good to Islam too”. Their love notwithstanding, that mystification of King Bhumibol as a god-like figure poses a theological and cosmological question for the residents to answer.

“We love Mr. King.”

One day, while we sat chatting at a roadside pavilion, I asked Kak Dah what she meant by the word “เรา” (Rao, or ‘We’) in the sentence “เรารักนายหลวง” (Rao Rak Nay Luang, or ‘We Love the King’) inscribed on a ceremonial platter. “Malay people,” she said. I then asked her if she felt uneasy about using that sentence, which is seemingly designed primarily for ethnic Thai people, and she said: “No. It’s OK for Malays to love the king”. So I asked Kak Moh, who also helped making the ceremonial platter, if she agreed with Kak Dah, and she replied that she did. She added that “We reside in Thailand, so we are Thai too”. This position was shared by others at the pavilion.

While the meaning of the word “เรา” (Rao) is straightforward, that of the phrase “นายหลวง” (Nay Luang) however is not. “นายหลวง” (Nay Luang) is indeed a misspelling of “ในหลวง” (Nai Luang), the phrase by which Thais refer to King Bhumibol. Alone with Meng, I asked what he meant by “Nay Luang”, and he said “the king”. When I asked him further what he meant by “นาย” (Nay), he explained that the term can have two different meanings, depending on the language used. In Thai language, “นาย” (Nay) means “Mister”, and the phrase “นายหลวง” (Nay Luang) therefore means “Mister Luang”, which may or may not denote the king. In Malay, however “นาย” (Nay) is part of the word “Toh Nay” which refers to Thai Buddhist government officials. When combined with “หลวง,” (Luang) the Malay word “นาย” (Nay) gives the impression of the chief of government officials – that is, the king. However, Meng added that, given that “Toh Nay” was used by Malays of previous generations, it is more likely that what the young platter makers meant by “นาย” (Nay) was “Mister”. And, given that “หลวง” (Luang) is usually related to the king, Meng said it is likely that many of the platter makers meant “นายหลวง” (Nay Luang), “Mister King.”

With Mung’s explanation in mind, I asked other platter makers the same question and received similar answers. Kak Dah said what she meant by “นาย” (Nay) was “Mister”, because the king is “a man”. She also added that local Malays pronounce “Toh Nay” in a different way, and that “นาย” (Nay) does not therefore refer to “Toh Nay”. Likewise, Asroh claimed he had hardly heard of the Malay terms “Toh Nay” or “Toh Nae”, and that, to him, “นาย” (Nay) is a Thai word which means “Mister.” In addition, both Kak Dah and Asroh agreed that “หลวง” (Luang) denotes either the king or something related to the king. As such, for these Malay platter makers, “นายหลวง” (Nay Luang) was a Thai phrase which, translated word by word, meant “Mister King.”

The fact that the phrase “นายหลวง” (Nay Luang) denotes the king but literally means “Mister King” is important. Although constitutionally regarded as the Upholder of Religions, King Bhumibol was re-mystified as a god-like figure through royal ceremonies associated with Hinduism and Brahmanism. His mythical and theological features pose a challenge to the residents because, as Muslims, they are not allowed to have any supreme beings other than Allah. The sentence “เรารักนายหลวง” or “We love Mr. King” makes it possible for them to accommodate King Bhumibol in their cosmology without compromising their religious principles. First, the word “love” denotes an intimate relationship and not an act of solemn worship or reverence. Secondly, the word “Mister” denotes a human being and not a god or a supernatural being. Taken together, “We love Mr. King” is thus the expression of an intimate human relationship, rather than an act of reverence towards a supreme being. It is the stripping King Bhumibol of his mythical and theological features what renders his inclusion in the Muslim cosmos possible.

After the Reign

The death of King Bhumibol not only brought a change to Thai politics, but also affected the ways in which Malay residents engage with Thai kings. Although the mystification process has already begun, it will take time for the present king to become a god-like figure in the eyes of his subjects including Malay residents. The question that Malay residents will need to answer might not be one regarding supreme-beings, but rather human beings.

Anusorn Unno

Assistant Professor, Dean of Faculty of Sociology and Anthropology, Thammasat University

Issue 22, Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia, September 2017

References

Anusorn Unno

2011 “We Love Mr. King.”: Exceptional Sovereignty, Submissive Subjectivity, and Mediated Agency in Islamic Southern Thailand. A PhD Dissertation, the University of Washington.

2016 “‘Rao Rak Nay Luang’: Crafting Malay Muslims’ Subjectivity through the Sovereign Thai Monarch,” Thammasat Review. Vol.19, No.2 (July – December).