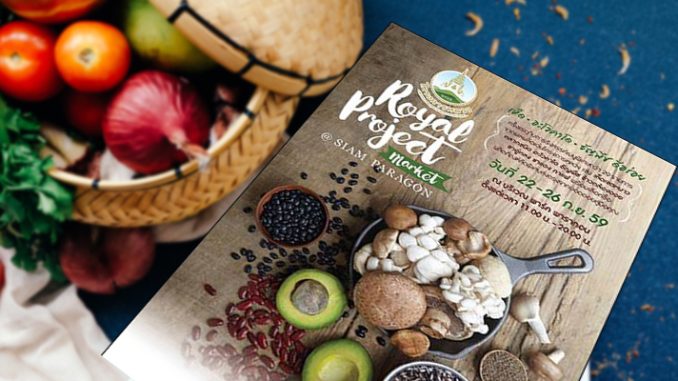

Between 22-26 September 2016, an exhibition was held in the small plot of commercial space that lies between Paragon department store and Discovery Centre in downtown Bangkok. The display featured products from the Royal Projects – development initiatives promoted by King Bhumibol over the course of his seventy-year reign. Inside the large white tent, cooled by portable air conditioners, bag-laden shoppers could indulge in such delicacies as Sautéed Mushroom Grilled Cheese with Raspberry Ketchup, while taking in the extravagant surroundings. A reconstructed mountain retreat, complete with fresh-planted flowers, wooden tables, and faux rural dwellings welcomed shoppers seeking sensual delight. The four large pictures of the then king, which hung from the ceiling above, were so ubiquitous as to be unremarkable.

They depicted Bhumibol at the height of his virility. In them, he was dressed in simple civilian or military garb, either on his own or with his Queen or daughter by his side and always surrounded by crowds at his feet. At the time they were taken, the Royal Projects were small-scale development programs run through the royal household. They were based largely in Thailand’s hill tribe communities, often in areas encircled by communist insurgency. They would also often involve a direct visit from the king himself. On one level, these visits to the edge of the kingdom, with promises of development, presented Bhumibol as a nation-builder; a Cold Warrior, whose example ran opposed to, but also alongside that of his contemporary on the other side of the world, Fidel Castro. On another, they evoked the perfect Buddhist king who was able to align himself to the international, and by extension, cosmic moment.

So what makes these images relevant to urban consumers today?

Timeliness

Good propaganda has to be timely. As Jacques Ellul (1973, 43) once explained, propaganda must strike a rapport with ‘fundamental currents’ that shape the present, and excite only through ties to ‘volatile immediacy’. In a world where basic facts pass swiftly into the realm of history, neutrality and indifference – propaganda must relate only to the ‘myths and presuppositions of a given time and place’.

Throughout the Cold War, two key forces created a sense of historical immediacy in Thailand: the threat of communism and US-orientated developmentalism. Back then, Bhumibol’s trips to the countryside spoke to both. Not only did they dramatize the supposed threat of insurgency, they also alleviated anxieties about the rapid expansion of capitalism that was now underway.

Crucially, this was not a single hegemonic project. It was multi-faceted, and managed through a complex set of reciprocal relationships that rewarded distinct acts of devotion with varying levels of access to royal iconography. For a while, the greatest beneficences were the Americans, whose support for Thailand’s monarchy in their own propaganda campaigns helped secure the royal image for the sake of beating communism. For most Americans visiting Thailand, loyalty to a king who committed to fighting their war was simply a given. Moreover, in a region that remained deeply suspicious of white westerners, the privileged position offered to Americans instilled a sense of obligation toward the Thai establishment, channelled largely into a respect for ‘traditional’ forms of cultural governance. This post-colonial moral order was instrumental in underpinning Thailand’s rapid integration into American-led capitalism.

Bhumibol the Cold Warrior has long lost its lustre. Yet, expert at reading emerging currents, the royal institution has reworked its reciprocal relationships to reflect new social and political realities. Like the Americans during the Cold War, those who have been willing to assert the centrality of the monarchy to everyday Thai life have been rewarded with a degree of access to the perceived moral authority of the king. This has, in turn, helped to infuse existing cosmologies, upon which Thai kingship relies, with renewed efficacy in an ever-changing world.

Fresh, Clean and Healthy

Today’s zeitgeist is cleanliness. Clean eating and slow food dominate Bangkok’s coolest locales. Promising to detoxify the body and ease the anxieties of modern life, clean food replicates the old colonial tropes of distinction once provided by soap and hygiene. As Anne Mcclintok (1995, 226) has explained in relation to the British imperial lather, ‘purification rituals prepare the body as a terrain of meaning, organising flows of value across the self and the community and demarcating boundaries between one community and another.’

In Thailand, where a ‘clean’ [sa-ad] plate of food is priced way beyond the ordinary person’s purchasing power, the global trends of ‘slow’, ‘organic’ and ‘craft’ offer new routes to bodily distinction and purity through an array of exciting culinary commodities. It also creates new spaces; pure, clean and refreshing sites that aim to delight an exclusive, hip, cosmopolitan clientele. Restaurants with names such as Ariya Organic Place [Ariya being the pali for pure, precious or noble], thus claim to exploit the latest science from abroad to nurture the urban body, but also assume a longer history connected to an internal Thai-Buddhist worldview. 1

The same can be said for the exhibition next to Paragon which in publicity material was both ‘decorated with woods to resemble the highlands’, but also based on ‘a contemporary farmers market’ that ‘catered to the demand and trendy lifestyle of urban dwellers and the new generation.’ 2 A fusion, therefore, of the internationally familiar with the culturally specific; exciting new recipes from celebrity chefs, served with a rustic, hipster flare, but with a Thai twist and a premium price tag.

Here, the grainy images of King Bhumibol, taken in a previous era, formed a vital part of a modern spectacle of the new. As his physical body neared the end of its time on this world, these images were stripped of their Cold War context. Now, they placed the spirit of the younger king at the centre of a purified [borisut] cultural world, replete with manifold opportunities to participate through small but highly charged acts of extravagant consumption.

Buying-in to the royal image

Throughout the ninth reign, wealth and purchasing power have been a primary means through which erstwhile outsiders have established a reciprocal relationship with the royal household. Christine Gray (1991) has explained how, at the height of the Cold War, Sino-Thai capitalists were able to ‘latch-on’ to royal virtue by contributing to royal charities and initiatives.

Meanwhile, Kasian Tejapira (2003) argued that, from the late 1980s, the rapid expansion of consumerism that accompanied Thailand’s tiger years helped create a more uniform sense of urban identity. Increasingly, being Thai was something that could be bought, or experienced, through an exchange of value. A holiday, an item of clothing, a piece of jewellery could all be made more attractive by associating it with something ‘Thai’. Separately, Somsak Jeamteerasakul (2013) has claimed that the emergence of this new consumer culture made it easier, and more attractive, for urban consumers to move into the orbit of the monarchy. Simple purchases of royally endorsed, or branded products, as opposed to the more traditional and ritualized expressions of devotion, offered a refreshing and distinct means to demonstrate a commitment to the nation.

Over time, however, these purchases also helped to substantiate the idea that cosmopolitan lives needed to be mediated through the image of King Bhumibol if they were to remain relatively free from moral complexity. Following the 1997 crisis, when the fundamental inequalities of the capitalist system in Thailand were laid so brutally bare, royal virtue became an even more highly prized commodity. Particularly from the period following 2006, commitment to monarchy offered reassurance to urban Thais who opposed the various governments associated with Thaksin Shinawatra; providing them with reassurance that they remained morally virtuous.

Myth and Action

While propaganda must be timely, the propagandist works to a more drawn out timetable. A good campaign must maintain a great focus if it is to successfully instil the myths that form the basis of everyday life. ‘By myth’, Ellul (1973, 31) explains, ‘we mean that what is needed is an all-encompassing, activating image: a sort of vision of desirable objectives that have lost their material, practical character and have become strongly colored, over-whelming, all-encompassing, and which displace from the conscious all that is not related to it.’ Only when such an image exists, can propaganda ‘push a man to action precisely because it includes all that he feels is good, just, and true.’

Over the course of the ninth reign, the mediation of cosmopolitan culture though the image of King Bhumibol has been vital in keeping monarchy fresh and relevant. But it has also served to reinforce underlying assumptions about the presence of a distinctly Thai cosmology. Beyond the contemporary narratives of the Cold War, the images that hung above shoppers were ubiquitous because they presented a greater ‘truth’ of Bhumibol’s assumed divine status. While his clothes presented him as humble, dutiful and austere, the flocking crowds at his feet told of a Buddhist King, full of boundless charisma, righteousness and virtue.

In the highly-sanitised environment of Bangkok’s most salubrious shopping district, the faux mountain retreat was more than clean or refreshing. It was a sanctified site that promised both physical and spiritual transformation; a farmer’s market unsullied by actual farmers that did more to evoke the first rung of Buddhist heaven than a place of lowly labour. With the King dutifully looking over them, in a shopping district which itself is elevated from ground level, devotees were thus spurred to acts of devout consumption.

Doi Kham company product.

Pure Grief in the New Thailand

Preparing for the King’s death was as inevitable as it was problematic. The wealth of messages that appeared on billboard’s and in newspapers in the aftermath of the death all had to be written, checked and double checked to ensure they conveyed the right meaning. Programs had to be scripted and edited, and articles had to be written.

The Doi Kham company is one of the most prominent to market royal project products, distributing fruit juices to major supermarkets as well as the Seven Eleven. In the months before Bhumibol’s death, the company’s products were also subjected to a major overhaul. Stripped of their garish green branding, the new products were kept clean and crisp. The white cartons featured distant mountains in the background, with the fruit in the foreground, and the royal projects logo embossed at the top. Building on their reputation of ‘cleanliness’ these products once again fused cosmopolitan flavours with the spiritual purity of Bhumibol. Through the lens of Buddhist cosmology, the design also evoked Mt Meru; with the fruit presented at foothills of the Buddhist heavens as a ‘gift’, and with the Royal Projects logo representing the summit.

In the aftermath of his death, on October 13, demand for the Doi Kham products rose sharply, with many consumers obsessively seeking out the rarest. In Thailand’s cosmopolitan cosmos, these acts of devout consumption are likely to continue as they become more clearly associated with a king whose physical presence transfigures into a spiritual one. Serving as relics of the late king’s virtue, these newly branded fragments of Thailand’s existent moral order hold a very special value to those who hold that relationship dear. Writing on the company’s Facebook page, one user who was seeking out a particularly rare product explained that, ‘Our Father hasn’t truly left us, because our father left us these good things that are useful [mii prayot] for all his children. I love our father, and I support these products that are expressions of his love.’ 3

Matthew Phillips

Lecturer in Modern Asian History

Department of History and Welsh History

Aberystwyth University

Issue 22, Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia, September 2017

REFERENCES

Ellul, J. 1973 (1962). Propaganda: The Formation of Men’s Attitudes [Translated from the French by Konrad Kellen and Jean Lerner], New York: Vintage Book.

McClintock, A. 1995. Imperial Leather: Race, Gender, and Sexuality in the Colonial Contest, New York: Routledge.

Gray, C. 1991. ‘Hegemonic Images: Language and Silence in the Royal Thai Polity’,

Man, New Series, Vol. 26, No. 1 (March 1991).

Kasian Tejapira. 2003. ‘The Postmodernisation of Thainess’, in Shigeharu Tanabe and Charles F. Keyes, Cultural Crisis and Social Memory: Modernity and Identity in Thailand and Laos, Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

Somsak Jeamteerasakul. 2013. ‘Mass Monarchy’, Yum Yuk Rug Samai: Chalerm Chalong 40 Pi 14 Tula, Bangkok: Heroes of Democracy Foundation and 14 Tula Committee for Democracy, pp. 107-118.

Notes:

- Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JIlWsjcC3MU ↩

- ‘Royal Project Market@Siam Paragon’ http://www.bangkokpost.com/lifestyle/whats-on/63523/royal-project-market-siam-paragon ↩

- Posted on Facebook in January 2017, my translation (identity of user kept anonymous). ↩